Unequal Encounters

Thomas Fillitz

Elpida Rikou’s chapter exemplifies well a feature that is common to all the essays in the section “‘Narratives:’ Framework and Contextualization”. Reading through her three short stories, having visited documenta 14 in Kassel, and having had the honor of participating in the closing conference of the research project, I wonder about this encounter between Athens and documenta. This first issue is connected to Nanne Buurman’s essay about the politics of re-presentation and the essay by Apostolos Lampropoulos’ on hospitality/in-hospitality. My other question involves the question of contextualization, the relationship between the work of art as tool of curatorial intervention and the city of Athens, which is the topic of essays by Kyveli Lignou-Tsamantani, Chrysoula Lionis, Peter Rehberg, and Alexis Fidetzis. Athens neither was, nor is, a blind spot of contemporary art, the latter being well incorporated within the European-North American history of art. In 2017, its art world relied on, among other things, a newly built museum of contemporary art with no financial capacity to operate, and, most importantly for the present purpose, the Biennale of Athens. Nevertheless, Athens is not such a hotspot of contemporary art as London, Paris, or Madrid.

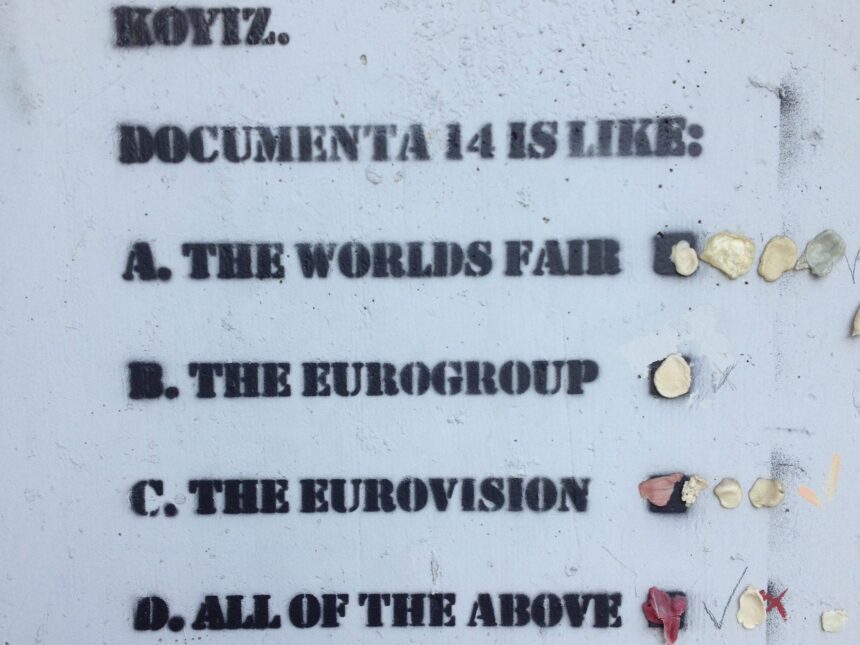

Now, what was the problem with this encounter? The travelling, large-scale exhibition? The touring blockbuster exhibition is a common practice, and a criterion of success. Also, Manifesta’s principle is precisely to re-locate each edition in another city. Collaboration as an equal partnership? In 2007, Art Basel, la Biennale di Venezia, documenta, and Skulptur Projekte Münster had joined for the Grand Tour, and in 2008, similar biennial collaborations can be found in the Asia-Pacific network.[1] Leaving the Structural Adjustment Program and its impact on social, economic, and political constellations aside, I focus my reflections on art world discourses. I see the heated debates in Athens in connection with the particular structure of documenta (cf. Buurman, this volume), and the unfolding of an unequal encounter (cf. Lampropoulos, this volume). Documenta is not any biennial within the global biennials network, the institution claims to be the leading exemplar of this format at a global scale, and this view is shared by many European and North American art world professionals. To reach this (pole) position, documenta has, indeed, contributed to new art world trends. For example, the idea of the superstar curator was institutionalized with documenta 5 (1975) by Harald Szeemann, who enacted the image of the curator as ‘inventor.’ While there has been an increasing interest in the global scope of contemporary art creation (and not as a monopoly of Euro-North America) for some time, documenta 11 (2002) constituted a major milestone in this respect. Okwui Enwezor, however, represented another stage of the curator as ‘inventor,’ namely the global curator. As Charles Green and Anthony Gardner elaborate, this new dimension implies the ability to include an ever-growing number of artists working at a global scale with their various (often cost-intensive) art projects, in order to conceptualize the exhibition as a field of curatorial experimentation, and to attract an international art audience.[2] This is clearly a very demanding process, involving levels of funding and logistical resources that few arts institutions can provide.

The institution documenta possesses the appropriate power for such experimentations with exhibition formats. In order to hold its leading position, however, the institution also needs to comply continually with another important requirement of the European-North American art world—innovation. Moving documenta out of Kassel had been done before, with documenta 11’s four platforms of debate in Vienna, Lagos, Delhi and St. Lucia (2002), and Carolyn Christov Bakargiev’s documenta 13 (2012), which experimented with small art spaces in Kabul-Bamiyan, Alexandria-Cairo, and Banff. Expanding the large-scale exhibition with documenta 14 (2017) was therefore a logical step, and from documenta’s artistic viewpoint fully appropriate as part of an effort to reinvigorate its claim as the global art-exhibition-event, while remaining well rooted in Europe. Hence, documenta 14 re-territorialised itself in Athens, according to its inherent logic and a self-image made in Kassel. The general curator’s concept of experimentation relied fully on documenta’s exhibition charisma.[3]

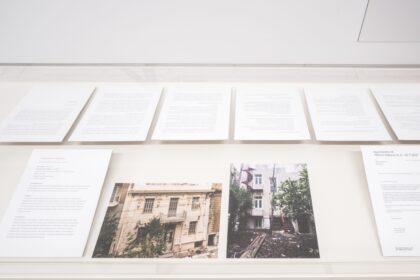

Most chapters in the ’Narratives’ section discuss this unequal relationship at the communicative level between the work of art and the curatorial concept. Fidetzis concludes her reflections on Bouchra Khalili’s video The Tempest Society (2017) by stating that the artwork’s critique of nationalism in the exhibition shifted, to become complicit with “a Greek national narrative.”[4] Lignou-Tsamantani elaborates on another aspect of this relationship regarding the exhibit at Pireos Benaki. As these works of art pictured “instances of violence, suffering and death” [5] in different regions of the world, she argues that the absence of information about their local impact impedes the beholder to experience an ethical stance. Indeed, the question of contextualization is especially crucial for exhibitions that operate in the realm of the global art world. In this context, art works can be de-territorialized from their local art world, re-territorialized next to art from another art “world,” situated within a framework conceived by the curators, and experienced by audiences whose capacities for visual experience are largely learned from within Euro-North America.

Here I’ll refer to the series of “realistic paintings” 101 Works (1973-74) by Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, one of Lignou-Tsamantani’s examples. This was a project the artist and the anthropologist Johannes Fabian conceived together in Lubumbashi, the capital of former Katanga.[6] Fabian suggested that the artist paint moments of the early history of Zaire, with Tshibumba Kanda Matulu being totally free to choose the events, and to picture them as he envisioned them. Later, Fabian would enact an equal narrative with the artist, in order to merge the artists pictures and his own interactive reflections (via personal communication from Fabian).[7] These paintings belong to the category of ‘popular art’ of the 1960s and 1970s. Artists associated with this art form would select their themes from among a few overall topics, one of the most famous being colonie belge, pictures of colonial violence in villages. Another typical feature of this art is that it often communicates on two levels, the image itself with an integrated text. Created for local buyers, to be placed in their homes, these works have “a capacity to activate memory and reflection”—Fabian’s interlocutors spoke of ukumboshi, which brings us back to the importance of the narrative relationship between artist and anthropologist. [8]

To describe these works of art within the European art historical concept of ‘realism’ is by and large misleading. The artist imagined the scenarios based on concrete historical moments, and neither the painted environments, nor the structure of the images, can be appropriately labelled as ‘realist.’ These pictures are elaborated according to the topics the artist wanted to highlight, they are not aiming at representing a scenario from real life. More importantly, considering this artist’s concern with communication, Tshibumba Kanda Matulu’s paintings would have demanded contextualization in order to facilitate narrative interaction.

The essays in the ‘Narratives’ section largely elaborate unequal discursive fields which determine documenta 14’s framework and specific contextualizations. At the structural level, I’ve argued here that documenta’s movement into the Athens art world appears as sedimentation of its flagship position by means of this new dimension of the global art-exhibition-event. As an aspect of the curators’ overall experimentations, contextualization proved to be an ambiguous technique: on the one hand it failed in respect to Bouchra Khalili’s video, and on the other its absence impeded adequate experiences of the works of art at the Pireos Benaki exhibit.

Thomas Fillitz is a retired professor of social and cultural anthropology at University of Vienna. He was visiting professor at Université Paris Descartes (2011), Université Lumière Lyon-2 (2008), Université des Sciences et Technologies de Lille-1 (2001, 2003), External Examiner at National University of Ireland-Maynooth (2003–09), and he taught at various universities in Europe. Thomas’ research focuses on contemporary art in Africa with extensive fieldworks in Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, and Senegal. His most recent research interest is the Biennale of Contemporary African Ar at Dakar, Senegal. Among his publications are: Dak’Art. The Biennale of Dakar and the Making of Contemporary African Art, edited with Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi (New York and London: Routledge, 2021); “The Biennial of Dakar and South-South Circulations,” ARTL@S BULLETIN, vol. 5, no. 2 (2016), pp.57-69. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas/vol5/iss2/6/ and “The booming global market of contemporary art,” Focaal 69 (2014), pp.84-96.

Notes

[1] See Charles Green and Anthony Gardner, Biennials, Triennials, and documenta. The Exhibitions that Created Contemporary Art (Malden, MA, and Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2016).

[2] Ibid., p.244

[3] Adam Szymczyk, “14: Iterabilität und Andersheit: Von Athen aus lernen und agieren,” Der documenta Reader, edited by Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (Munich-London-New York: Prestel, 2017), p. 22.

[4] Alexis Fidetzis, “Romanticizing Reaction: Thoughts on Bouchra Khalili’s The Tempest Society”. This volume: p. 2.

[5] Kyvely Lignou-Tsamantani, “The ‘Death’ of the Unknown Spectator: documenta 14 exhibition at the Pireos Annexe of Benaki Museum, Athens“. This volume: p. 6.

[6] Ibid., p. 5.

[7] See Johannes Fabian, Remembering the Present. Painting and Popular History in Zaire (Berkeley-Los Angeles-London: University of California Press, 1996).

[8] Johannes Fabian, 1998, Moments of Freedom. Anthropology and Popular Culture (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, p. 51).