Organizing: Collectivity as Infrastructure in Southern African Arts Practice

Molemo Moiloa

What are the infrastructures that enable creative practice and a politics of the public? What are the networks of production and the socio-political time/space that enables this form of work? This article is an explorative exercise in thinking through collective organizing as a strategy for social infrastructures that enables practice outside of (or alongside) formal state structures and commercialization. Thinking through histories of arts infrastructures in Southern Africa, I argue that for social practice art to proliferate across the region, young artists are recognizing the need to develop new infrastructures of support for this kind of work. By and large, these infrastructures are social and collective. They respond to the complexities and socio-historical injustices of their contexts, and seek forms of organizing praxis that are as radical as their creative work. This research emerges out of work developed by the Visual Arts Network of South Africa (VANSA) from 2016 – 2019 [1], and a range of discussions and workshops undertaken to communally explore collective practice in the Southern African region. Through various interviews with practitioners across the region [2] and a review of the limited literature on current frameworks for support of the arts, this article tracks some perceived questions and emerging approaches. It begins with a relatively sweeping overview of arts infrastructure in the Southern African region, discusses Abdoumaliq Simone’s concept of social Infrastructure [3] and applies this to the practices of a number of collectives from across the region.

Artists that might look to develop work that responds to, and engages with, their immediate social conditions (let’s call this social practice art) require fit-for-purpose infrastructures of support to enable the proliferation of this kind of practice. To begin with it might help to briefly frame what is referred to as social practice art. I would define this broadly as a social justice-oriented art practice. This involves a kind of political praxis that undertakes an actual tangible social engagement, rather than limiting itself to artworks that have politically oriented content (a painting in a gallery critiquing a political party for example). As I have discussed elsewhere [4], this refers to a kind of practice not limited simply to a welfare-type orientation (doing good deeds through art), but rather speaks to a political commitment, the very nature of a praxis that folds the aesthetic/artistic/intellectual process into the social, and therefore also into the political.

In much the same way that art schools, galleries, auction houses and museums intertwine to create a broader market-based framework for artists producing work primarily for sale, a latticework of support, development, financing and discourse is necessary for social practice art. This latticework is particular and requires a varied offering that intersects with, but is distinctly different from, the broader art world framework. To enable such a practice, and to strengthen its discourse, complexity, ethics and rigor requires an infrastructure of complex social relations and intellectual engagement. This requires arts education programs that encourage collaborative and public practice, critique and theorization. It requires funding forms that enable emergent processes, support human resources over and above object-based outcomes, and long-term trust building progress rather than short-term project-based deadlines. It requires networks, organizational models or even institutions – and especially skills – that grow, nurture and maintain community relations beyond the limitations of the worlds of art and the academy. It requires art-world linkages to community mobilization, social justice networks and activist entities. Largely, in Southern Africa, this infrastructure doesn’t exist.

Colonial Approaches to Arts Infrastructure in Southern Africa

Arts infrastructure across the region primarily falls into one of two categories: the first is colonial-era arts venues and funding structures, initially built for Euro-American style art forms and ‘expat or settler’ audiences. The second is Independence-era infrastructure built as part of nation-building and social-cohesion agendas and informed by some combination of colonial inheritances and pan-Africanist imaginaries. A brief survey of existing institutions across the region points to distinct differences between colonial powers’ historical provision of arts infrastructure [5]. The British colonial authorities primarily provided more infrastructure in their colonies than the Portuguese, Germans or French (in Angola/Mozambique, Namibia and Seychelles/Reunion/Madagascar respectively). At minimum, across colonial powers, each country was generally provisioned at least one theatre/concert hall and potentially one museum/gallery in its main city, with the distinct exceptions of the French islands of the Southern African region, and a few other countries [6]. In Zimbabwe and South Africa, and later Namibia, this extended to large-scale arts council type formations that ensured creative expression across the country and enabled local production (including that of black artists) of creative practice outside of the narrow settler productions that were the mainstay across the region [7].

Outside of state systems some parts of the region had higher levels of private or corporate support for creative expression that supported commercially viable creative expression. This was also extended to local populations such as dance, choral and theatre groups created for workers on farms and mines; and through the spread of the church such as choirs, composers and formal creative expression training through mission programs and schools [8]. Within the British Colonies (and South Africa and Namibia) creative works by black practitioners initially entered whites-only infrastructure through colonial and anthropological collecting, and in some countries, as recognized art practice by artists by the 1950s – for example the inclusion of Zimbabwean Stone Sculpture in the Rhodes National Gallery in Salisbury in the mid 50s [9] – reaching a high point in the late 70s in music, visual arts and theatre. In many parts of the region this marked a significant shift away from active repression of pre-colonial creative expression, even if still very much within the purview of settler control [10].

Independence and Post-Independence Approaches to Arts Infrastructure in Southern Africa

While colonially inherited infrastructures coalesced, a new kind of arts infrastructure emerged during the steady liberation of the region in the last decades of the 20th century. The independence era in Southern Africa spans from 1964 to 1994, with at least half the countries in the region gaining independence after 1970 and almost another quarter after 1980 – making Southern Africa the youngest independent region on the African continent. As with independence-era ideology across the continent [11], much of Southern Africa considered creative expression key to the creation of new independent nations. This resulted in significant infrastructure development in the region after their respective independence dates. In many countries this included a increase of access to infrastructure beyond main cities into all provinces of the country, particularly Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe [12]. It also included significant infrastructure and grant support funding with a revised focus on indigenous practice and indigenous practitioners such as in Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique [13]. The vision of supporting artistic practice at this time was primarily aimed at nation building and cultural ‘harmony.’ This often meant a tendency toward quite generic cultural identities and expressions that were aimed at positive affirmations of independence narratives with very little space for critical dialogue or expressions of alternative identities – particularly those outside of nationalist and liberation party meta-narratives.

Across the region however, this upsurge in cultural expression infrastructure development was short lived. The combination of structural adjustment policies, increasing criticality from cultural practitioners and long-standing political turmoil and economic stagnation resulted in cuts to funding for infrastructure and a slump in political will. In extreme cases cultural expression has been censored and even banned, for example in Zambia in the 70s and 80s, South Africa intermittently and Zimbabwe till the current moment as chronicled in the ongoing Artwatch Africa reports [14]. Development of new infrastructure has largely stalled, and most arts institutions across the region are significantly underfunded. To some degree colonial era infrastructure has been the primary loser, as the limited funds that are available to the arts are prioritized for ‘postcolonial’ production. An interview with Maswati Dludlu [15], a theatre practitioner in Swaziland, indicated state funding is only available for programming oriented towards the Royal Family or Swazi Traditional Culture, and many similar complaints emerge across the region. There are a number of state entities that remain active, internationally engaged and impactful in their field. The National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare which drives Zimbabwe’s representation at the Venice Biennale, or the South African Market Theatre in Johannesburg which co-produces award-winning plays with international festivals and theaters such as the Manchester International Festival, are some examples among a few others. Private institutions, including music schools, commercial theaters and galleries and increasingly some privately funded foundations continue to drive much of the more contemporary practice in the region, but are mostly accompanied by a hefty price tag, an elite client base and limited social engagement or responsibilities. Creative practice that is oriented towards a wider audience base, and to addressing present and historical inequalities, is largely undertaken by non-governmental organizations funded through international donors, particularly from Europe. These non-profits remain precarious due to the limited funding in the region and tend to orient toward ‘development’ agendas – education and training primarily. A number of organizations and artists interviewed expressed some frustration at the impact of development donor agencies that color the nature of production due the specificities of what they fund. One example regularly given was the proliferation of AIDS-related art production in order to align with donor agendas [16].

Arts education infrastructure largely suffers from similar limitations of state funding or political will. Whether colonially developed or initiated after independence, very few art schools are able to keep up with international trends, modernization and the expectations of young students. Various insights into arts education [17] across the African continent point to recurring concerns. What formal education exists is often too expensive for the majority of people who are interested, and then is likely to be highly theoretical and outdated, not to mention under-resourced as regards professional equipment etc. Across disciplines, research points to the arts being primarily made up of auto-didacts who have been unable to access education. Where education is accessible, whether through universities and colleges or more informal NGO-driven training, much is still directed towards creative practice, with very little training towards managerial, administrative, financial and technical roles.

Social Infrastructures as a Response

It is into this infrastructural context that young arts practitioners enter. The infrastructure that exists is buckling under the weight of the broader challenges of the region. What is functional is either commercial and therefore expensive, or has its roots in historical contexts quite different from contemporary needs, and is struggling to respond to change. For social practice artists, in particular, the existing infrastructure is inadequate to handle the complexity of subject matter, approaches and strategies that this practice requires. It is within this context that young practitioners are having to chart alternatives, and strategies for production that better suit their intentions and interests. Linking into existing infrastructure, but pushing beyond its limitations, young arts practitioners across Southern Africa are increasingly looking beyond existing infrastructure, to develop their own. There is a shift, it would seem, towards a rhizomatic and lateral approach to creative practice. Leaving behind it the idea of the singular genius artist, this new strategy recognizes community, ideas sharing, multiplicities of skills and the energy of cross-disciplinarity. Collective and collaborative work is increasingly carving out space in the Southern African creative landscape as a kind of infrastructure that enables more contemporary forms of art making.

Abdoumaliq Simone points to the broader phenomenon of Africans producing their own infrastructures in response to the inadequacy of existing formal ones. People as Infrastructure (2004) argues for the recognition of an innovative and complex weaving of people-based networks and relations that enable the continuity of economy and production even without the support (or limitations) of formal state- and capital-based infrastructures. People as infrastructure combines with what infrastructure is available (some roads, and some formal financial systems such as mobile money) but builds upon it additional frameworks of sociality that are necessary, and outside of, formal systems of support and commerce. Indeed, it is the very limitations to infrastructure that make this innovation and independent orientation possible, as Simone states, “The truncated process of economic modernization at work in African cities has never fully consolidated apparatuses of definition capable of enforcing specific and consistent territorial organizations of the city.” [18]

Simone’s People as Infrastructure is important for a number of key reasons. He points to social networks as a fabric that makes possible what would otherwise be impossible, and that the determination of “possibility” is fluid and responsive to context and need. He also identifies the potential of significant escalation of impacts from very limited resources, due to the multiplier effect of interconnected social frameworks. And lastly, and perhaps most vital for this discussion, he reasons that there is a distinct intertwining of the very fact of a social infrastructure, ensuring a higher probability of a social impact – in effect he argues that the form is vital to the outcome. He states:

With limited institutional anchorage and financial capital, the majority of African urban residents have to make what they can out of their bare lives. Although they bring little to the table of prospective collaboration and participate in few of the mediating structures that deter or determine how individuals interact with others, this seemingly minimalist offering – bare life – is somehow redeemed. It is allowed innumerable possibilities of combination and interchange that preclude any definitive judgement of efficacy or impossibility. By throwing their intensifying particularisms – of identity, location, destination, and livelihood – into the fray, urban residents generate a sense of unaccountable movement that might remain geographically circumscribed or travel great distances. [19]

This very specific technology – of people as infrastructure – is a useful frame from which to consider the kinds of organizing emerging among young practitioners within the arts across Southern Africa. Because it speaks to the ways in which practitioners are determining alternative and interlinked infrastructures that make the work they want to do possible, but also in its very form generates the foundations of the work they want to do in and of itself. Artists and other arts practitioners interested in social practice art, are creating the frameworks of support to enable this art, through a kind of social practice. For the purposes of this article, we will refer to ‘organizing’ to name this kind of development of a framework for the support of social practice art production, that functions in collaborative and collective forms.

The first step is perhaps to say that collective art making practices are in no way new to the continent, entities such as the Zaria Art Society in the 1950s in Nigeria [20] and Laboratoire Agit’Art in Dakar in the 70s [21]) among many others, are the definite precursors of this practice. This history is vital to the ongoing proliferation and strengthening of organizing on the continent. I have written elsewhere about this history as it regards the South African context [22]. In some cases, a social practice art element is deeply embedded in the collective’s approach. One such key example is Medu art Ensemble, based in Botswana in the 1980s. Thami Mnyele, one of the leaders and eventual martyr of the Medu Art Ensemble, and one of the key conceptual drivers of social justice-oriented art critique from Southern Africa, wrote:

One of the most effective weapons against our problems should be organization and organizing skill. But the supreme purpose for organizing cannot be achieved without deep social or political awareness. Therefore awareness, in this context, implies the state of being organized; it denotes commitment and conviction; true political consciousness is the seed of collective spirit and democracy. [23]

There is an interesting intersection between this statement by Mnyele and the concept of People as Infrastructure, that claims a direct correlation between outcomes and organization – that the structure determines its fruits. Mnyele’s statement is also valuable when considering this inheritance of social practice art, which is the entanglement between the creation of artworks (or a kind of aesthetic interest) and the organizing that happens around and enables it. Member of Indonesian Collective Kunci Cultural Studies Centre, Ferdiansyah Thajib, discuss this entanglement well. He states:

Doing so does not imply that we desire to prolong the confusion between art’s autonomy (its position dissolved of social role and function) and heteronomy (the collapse of art and the social) here. Nor that the aesthetic dimension of a collaborative artwork needs once again to be downplayed for its social efficacy. (In fact, the deployment of notions of efficacy, ways of working and intentionality as criteria of judgement on what ‘good’ collaborative art should look like, may fall short against multiple modes of working together that have historically and effectively developed in the different locales delineating Southeast Asia as well as Indonesian collective art production.) We are more interested instead in engaging with a holistic approach that will allow us to consider the different junctures where the multiple aspects of a collaborative artwork meet: the aesthetic and the social folding into and out of each other as the work continues to unfold across time and space [emphasis mine]. [24]

Thajib speaks to the very complex intersection of three core things: aesthetic value, and social/collaborative (what we might call organizing) value. His enmeshing of the social and the collaborative speak to this direct connection between the means and ends – that a socially oriented art requires a socially oriented praxis in its production. And that this praxis and social orientation ebbs and flows with aesthetic considerations in complex ways that are as much about process as about some eventual ‘art work.’

Contemporary Collective Practice as Social Infrastructure

There seems to be a relatively recent proliferation of collective practice across Southern Africa, that builds upon the longer tradition discussed briefly above. The particularities of this recent proliferation differ in some ways to its predecessors due to the specificities of this context at this time. The Southern African creative space is deeply entangled in the political shifts that present an entirely different social, political and economic space to the practitioners of the 1970s, 80s and even 90s. Neoliberal priorities, austerity, crumbling independence narratives and increasingly youthful populations emboldened by the connectivity afforded by global technologies, means a region in flux, and a shift in creative practice in response. I argue that this shift might be characterized by a scale of collective engagement that is oriented towards a kind of self-organizing, that creates its own kinds of infrastructures to support an artistic practice that is socially oriented. A number of young arts practitioners within collectives across Southern Africa point to this, with some key strategies for organizing that have significant infrastructural impacts, that drive social practice art, and importantly that seek a synthesis between these infrastructures and this social commitment. What follows is a discussion of some of these collectives and the kinds of social infrastructures they build, and in particular, the strategies they use to seek a just social infrastructure.

To begin with, a number of collectives look to capitalize on existing, though limited infrastructures, and seek to multiply their impacts and open up access. By doing so they recognize an existing inheritance of infrastructures and seek to expand it. This is partly done through partnership and collaboration, but also through practitioners who enter into formal structures, leaving the proverbial door open.

Fstop Club is one such example. Fstop Club is a photography based collective in Johannesburg, South Africa. Their work is focused on reconsidering the space of critical photography alongside (rather than entirely outside) the elitist and limiting contemporary art and gallery framework. Primarily this plays out in considerations of photography distribution – working through public forms of visual consumption, self-publishing and zine making. Their work attempts to engage publics in existing black photography archives – often in the form of domestic family albums from South Africa’s townships – and to encourage a broader engagement with the social meaning and potential of these images. Another key part of Fstop’s work however, is the gathering together of young practitioners for collective critique, training and skills sharing, which they coordinate and host on a regular basis.

Their strategies of organising are interesting for a few reasons. The peer-to-peer spaces they have developed look to address some of their perceived limitations to existing photography training – often discussing subjects outside of what is covered in existing programs such as copyright issues or self-publishing strategies. They work with both formally trained practitioners and auto-didacts, creating a response to the infrastructural limitations of their context. Yet at the same times, their sessions have been hosted in various venues – whichever they could get – such as homes of photographers, art spaces and very often at the Market Photo Workshop, a non-formal but established education institution of photography. This points to a kind of interweaving within and building upon existing infrastructures with additional people-based peer-to-peer infrastructure. Furthermore, they actively articulate [25] an interest in resource distribution through their way of organizing. Where they are able to tap into formal infrastructures with associated resources, they actively look to spread the potential of those resources as widely as possible – looking to compensate even those they call on for favors, and to enable access to other kinds of resources such as libraries, working space, etc. Fstop Club’s strategies point to the limitations of existing infrastructure’s provision and support, as well as its potential to distribute resources. Their work then turns to the creation of a socialized, networked alternative.

The potential of distributive practices has also driven the nature and culture of Inkanyiso, a photography-based LGBTQ+ organization initiated by South African photographer Zanele Muholi. Inkanyiso is a registered non-profit organization, but explicitly expresses their identity within a collective-based tradition and cultural orientation [26]. Their work is focused on creative expression particularly among black and township-based young people who identify with LGBTQ+ affinities. Their work is directly oriented towards safe spaces for exploration, community making and creative expression within the South African contexts which is especially violent and hostile to black woman-identifying individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds. Their work is a deeply political and urgent work that creates a queer infrastructure of both creative and social commitment, that is otherwise severely lacking. While they run a range of different workshops and programs, one of their key directives is to enable access to more formal photography education spaces (and the Market Photo Workshop, in particular). This is done through collective resource pooling, led primarily by Muholi, but also from a broader committed community around and within Inkanyiso. Furthermore, the networks and opportunities increasingly enabled by Muholi’s internationally prestigious career are also targeted for further diffusion. Various people within and around the collective are brought into projects, associations and processes, both through Muholi’s work and also independently.

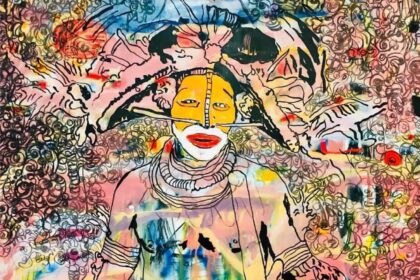

A collective such as Village Unhu in Harare serves as an informal training, studio and creative community space for many young practitioners. While studio space is rented, the organizers of Village Unhu regularly arrange alternative payment strategies or arrange with different collectors to sponsor studio space. As successful artists themselves they leverage their own networks to expand access for many of the new voices in the broader Village. They also serve as an experimental gallery, giving many of the young practitioners from their studios their first tastes of group exhibitions within a supportive environment. Again, in similar ways to Muholi and others they leverage their own professional reputation as individual artists to garner associative value for the other artists on show, creating a different kind of value infrastructure. Very often these distributive strategies are also about enabling wider access to education, and are driven by formally trained practitioners who may also have some industry experience, who then share their learnings. This responds to the general lack of access to education in the region, with very few arts education spaces and high fees in many cases. It is also a response to the limitations of curriculum that does exist, which largely excludes practical industry knowledge and experience around professional artistic practice, as well as the broader roles within each industry that surround the artist.

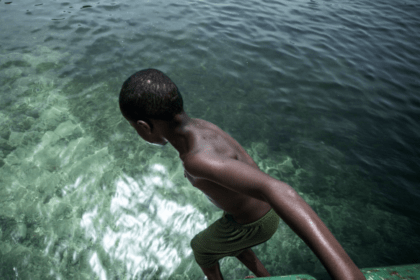

Maswati Dludlu, a theatre practitioner and activist in the creative expression arena in Swaziland, gave an important and poignant anecdote: in the face of very limited school drama programming, no tertiary level training in theatre, and not one formal theatre space in the entire country, the only way for young people to access the professional theatre environment is through joining an informal theatre group. Through the organizers of these groups, young interested theatre practitioners then learn to act, direct, write plays and manage technical equipment according to their interests and the skills available in the group at that time [27]. These groups act primarily without formal funding, without major formal infrastructure, buildings or offices and largely in collaboration with other groups.

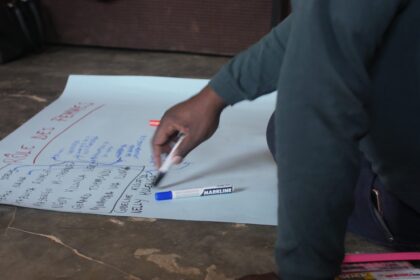

This is also visible at the Henry Tayali Art Centre in Lusaka. The centre was developed by the Visual Arts Council, a network of individuals who came together to organize the arts. The Council, now significantly formalized and subsumed into the governmental National Arts Council, was able to fundraise for the development of a large studio space called the Art Academy Without Walls, adjoined to the Henry Tayali Art Centre. While much of the funding for the studio has long since dried up, the artists that use the space have become its organisers, creating a lateralised organising structure – under the main auspices of the council. This organising structure includes the informal mentorship and apprenticeship of younger artists. Enabling the support of young practitioners is a key role of these groups; so that even where practitioners may not be able to access formal training, none can be said to be ‘self-trained’. As Andrew Mulenga, writer and chronicler of the Zambian visual arts scene explains:

there is a crop of young artists who are, for lack of a better term, trending right now. You can’t really say they are self-taught. There is an informal system of apprenticeship, which is very encouraging. Especially if you pass through the Art Academy Without Walls you will find an artist who is more established who will have three or even four younger artists there, training under him informally. Not doing exactly what he or she is doing, each has their own style. But they have a kind of mentor, who comes and checks over their shoulder and says oh that color . . . or that figure drawing is off, etc. [28]

These collectives are therefore creating complementary infrastructures that expand and multiply the potential of existing infrastructure, and where none exists, they attempt to fill the gap. We see them take up very practical roles such as education and resource distribution. These very practical roles serve the purpose that would be expected of formal infrastructures such as universities under different socio-economic circumstances. Importantly, where they might take on orthodox roles such as education, these roles often play out in unorthodox ways. The approach to mentorship and apprenticeship tends to be a more dominant pedagogical approach than actual teaching or lecturing, for example. This extends to the ways many of these collectives attempt to construct the metaphorical ‘bricks and mortar’ of these infrastructures. Rather than attempting to copy or adopt directly the natures of formal infrastructures, these collectives seek forms and approaches that best represent the social practice to which they are committed. In many cases this means identifying very clearly their political objective and then working towards organizational forms that, in their very operation, uphold those political objectives. This is a challenging process, dependent on many voices, various strategies, and a complex navigation of political or ideological approaches.

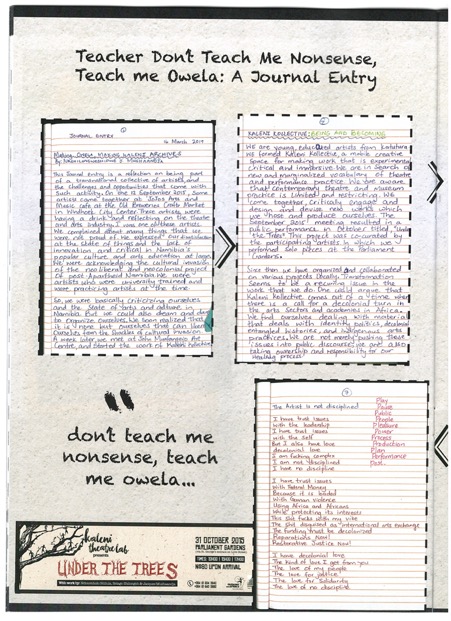

Kaleni Kollective is one such collective that articulates a distinctly political agenda and makes a practice of enacting its political approach. Kaleni Kollective is a multi-disciplinary collective based in Windhoek, Namibia. Initiated by a number of young performance-based practitioners, the collective hosts a range of practices and functions in quite porous ways, including practitioners from Germany under the auspices of the first Owela Festival. Owela Festival is Kaleni Kollective’s primary project, which includes performance, public engagement programming, a publication, education programmes and screenings. They describe the broader Owela project – which is inherently collaborative and works with wide networks of practitioners across Namibia and further afield – as reflecting on “historic intersectional worker struggles and solidarities around the world. [with] contributions from different scholars and practitioners working in areas of artistic and performance praxis, critical spatial praxis, radical histories and queer-feminist activisms. It is a critical reflection and invitation to imagine futures that suggest trans-historic and trans-temporal decolonial praxis, an overdue assignment” [29]. Kaleni Kollective have also published some insights into their working processes and the challenges of realizing their politic in their organising. Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja in particular has reflected on his own learnings in the collective process, he states:

Being Part of a collective is empowering and important because we get to create dialogue and forge collaboration. It is encouraging to create a safe and trusting space to develop ideas and build a future. However, collectives are also difficult and challenging spaces. I have learned that there will always be interpersonal challenges in spaces of organizing. These issues often have to do with our individual baggage of problems we haven’t dealt with. Collectives challenge our lack of accountability and transparency. Sometimes these challenges are a result of our toxic behaviors and a refusal to let go. Collectives are spaces that test our solidarities. [30]

Kaleni Kollective is made up of a number of artists who already established independent practices and establishing careers, many of whom are part of other collectives and/or organize other festivals or participate in more formal organizations and full-time work in formal state entities. This points to an intentionality in the potential for collective work, and a strategy of collaborative processes to best address key political concerns both within the production of art works, but also in how they organize and operate. Member of Kaleni Kollective, and also a driving force of collaborative Da-Mai Ensemble, Trixie Munyama, speaks to the need for these safe spaces to enable the complexity and challenge of being the kind of artist and organizer that she is, she states:

- There’s a need for new thinking in the training, creation and production of art. Old existing structures have failed younger generations because they are still stuck in outdated modes of thinking and doing art. This is specifically in observation of the Namibian landscape, in which a few cases are toxic, patriarchal, elitist and misogynistic spaces. 2. As a result of this, a generational conflict will erupt, to the detriment of the work that needs to be done. 3. In these cases, feelings of frustrations, anger and inadequacy build up within the psychological, physical and crucially spiritual practice of those involved on the ground. […] This is crucial to the artist, to develop her own way of dealing (confronting) with what’s at stake, unpacking and eventually unlearning in a safe and open space. [31]

Both Munyama and Mushaandja point to the concern of making safe space for “whole individuals” with political contexts, social challenges and historical impacts and how their work might enable a space that acknowledges, supports, challenges and potentially even heals complex individuals of tangled contexts. The collective becomes a safe space but also a space of accountability, in which the political agendas they seek are made actual. This kind of approach requires a multiplicity of skills and maturities, as it requires much more from the practitioner than to simply deliver on a job description for pay. Maun-based Poetavango approaches this specifically to bring in these skills, and recognize their professional potential. Poetavango is a collective that drives programs, education and public engagement with poetry in Botswana. In 2011, Poetavango initiated the Maun International Poetry and Spoken Word Festival, and in the years to follow, Poetavango expanded its platforms to include workshops for young writers, collaborating with the Okavango artists association. They work with various activist organizations focused on disability and homelessness, driving workshops aimed at the potential for creative expression through poetry around key issues within the context. Much like what Munyama and Mushaandja point to, the complexity and affective labour of this work can become challenging. Poetavango includes a trained social worker as part of the team, who supports moments of conflict, challenge and also of care within the collective [32].

These very specific strategies towards care and considerations of the challenges of organizing as political (or a question of solidarities), points to an integration of social practice agendas into the nature of organizing. Importantly this form of practice attempts to resist hyper-production, toxic (often gender oriented) hierarchies and burn-out culture, in favor of a political position of care and recognition of the “whole individual.” This is not to claim that they are fully successful. Rather it is the articulation of the need, and in the case of Poetavango, the integration into the infrastructure of the collective, that points to a political commitment. Where Poetavango brings in specific individuals who may be able to address some of these issues, collectives such as Kino Kadre and Toyi-Toyi collective have developed complex modes of working and organising structures that seek out alternative ways of being together, and organising together.

Kino Kadre, a film collective based in Cape Town, works solely by self-determined, non-hierarchical strategies. Kino Kadre is an informal organization that operates through “circles.” Circles are flat horizontal organizing structures that consist of film artists and activists that are interested in building their African Kino movement. Within the circles, consensus is built, plans are decided and work is accounted for. The circle is also the place where grievances are raised and dealt with. All participating activists appointed to tasks are subject to the recall of the circle. Eugene Paramoer, one of the core members of Kino Kadre, speaks to their specific approach to labour and its political intentions in how they structure their organizing. He states:

When KinoKadre speaks about the “violence of process” and the “violence of hierarchy” it is a notion or rather linked out to the process of project results. So we don’t believe that activists should be harassed, chased or seduced to meet deadlines, we put notions and reasons out there and invite people, so they can choose where they want to situate themselves in the circle, using the process of working with the people who are present. Working with those who are present simply means all activists have the democracy to share their choices and information but ultimately if they chose not to be involved directly in the work, they allow others to continue with the work. [33]

These organising strategies create a kind of alternative infrastructure for production better suited to their social practice art. A radical political agenda for self-determination in the townships of Western Cape, South Africa, requires an entirely autonomous orientation to organizing. They articulate their work as the critical need for consciousness raising discourse and provocative street art to counteract the “avalanche of mind-numbing content out there and the need to build a cinema of the broke by the broke and in the interests of the broke.” [34] As such this consciousness oriented organizing strategy would act in contrast to the problematic structures of labour, capital and control that they seek to conscientize against.

Similarly, Toyi-Toyi Arts Kollective, a street art collective based in Harare, Zimbabwe, operate in an entirely non-hierarchical, anti-authoritarian and autonomous model in correlation with their activist program towards social justice. Furthermore, their street art and creative collaborations across the African continent link into their political agenda, focusing primarily on public, accessible and anti-authoritarian creative expression. In the interview for this research Biko Mutsaurwa Chisuvi explains that,

Our processes are sometimes very slow and cumbersome. We are committed to them because we are a revolutionary counter-culture. We are the embryo of the new revolutionary society in the body of the old and the sick, dying one. We are the new lifestyle in microcosm, which contains the new social values and the new collective organizations and institutions, which will become the socio-political infrastructure of the free society. [35]

Part of why these kinds of strategies become vital is that the approach to organizing is based on distinctly political, ethical and even “psychological, physical and crucially spiritual practice,” to use Munyama’s phrasing. The social nature of organizing, and the imperative of social practice art, results in a personal and rooted approach to the work – what we might refer to as affective labour. At Village Unhu for example, founding member Georgina Maxim is known to regularly cook meals for all the artists and broader community at the village on a given day. In much the same way that Kaleni Kollective, Toyi-Toyi or Kino Kadre speak to a deep-felt conviction, and affective relation to their practice, Maxim’s labour emphasizes the social (and in this case a radical domestic social space) as a political position. Nuraini Juliastuti describes this kind of labour that exists across lines of formal work and production of the commodified sort, as well as a more personalized, care-based and relational agency. She says:

These are the kinds of friendships that border on partnership. Collaborators in a partnership can be friends. While building on a state of shared emotions and trust, […] friendship can be seen as a labour association from which a partnership can potentially be constructed. [And] If being in a friendship is to possess readily available wealth, or rather labour, how can the wealth that emerges from friendship be defined? [36]

An infrastructure built on affective labour implies a radically different network of social relations and carries with it a different framework of value and production. It is also potentially rife for exploitation and requires managing, and as Munyama indicated, care and self-care. However it also has the potential to strengthen the base of People as Infrastructure, to create dynamic, responsive and socially oriented formations, spaces and support to social practice art. A key point to consider here that exceeds the scope of this article but which I have discussed elsewhere [37], is the significant role of women and queer-associating practitioners across the various organizations discussed, and the potential for a political orientation that emerges out of these positionalities to create a greater orientation toward affective work and affective infrastructures.

Arts practitioners across the region are taking up this particular kind of relational labour to develop interlinkages that collectively make up a kind of social infrastructure of people who enable social practice art. These practitioners become an infrastructure of resource distribution, of education and training, of professional career making, of intellectual, social, emotional and political solidarities, and of a criticality of practice. Importantly these practitioners, committed to a social practice art, are determined to seek strategies to build an infrastructure that itself, practices the social commitments of the social practice art they develop. By linking into, and building upon existing infrastructures, and regularly working with young people and educational forms, these often informal and self-organized collectives supplement and fill the gaps of the limitations of contemporary arts infrastructure in Southern Africa. They do so through a deep commitment to collective practice, to social justice issues, and to a critical aesthetic interrogation through art.

Molemo Moiloa lives and works in Johannesburg, and has worked in various capacities at the intersection of creative practice and community organizing. Molemo’s academic work has focused on the political subjectivities of South African youth. She is one half of the artist collaborative MADEYOULOOK, who explore everyday popular imaginaries and their modalities for knowledge production. She currently leads research at Andani.Africa, with a focus on open restitution debates and is a sessional lecturer in the History of Art Department at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits).

Notes

[1] The initial research was undertaken under the auspices of a Ford Foundation Southern Africa grant considering New Voices: New Narratives in 2016/17.

[2] Interviews were partly undertaken by Lauren von Gogh, Tarryn Mckei and Naadira Patel, my gratitude to them for their research, inputs and comradery

[3] AbdouMaliq Simone, “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg.” Public Culture, vol 16, no 10 (2004), 207-249.

[4] Molemo Moiloa, “Remaining In Difficulty with Ourselves” in Wide Angle: Photography as Participatory Practice, edited by Terry Kurgan and Tracy Murinik (Johannesburg: Fourthwall Books, 2014); Molemo Moiloa, Organising: collective, collaborative organizing in Southern Africa (Johannesburg: VANSA, 2019).

[5] These findings are based on a series of interviews by VANSA for the report to Ford Foundation on Organizing in Southern Africa. This seems to be a largely unaddressed area of study, with the statements here relying primarily on anecdotal evidence as well as inference from studies on other areas of colonial infrastructure. Significant study has been conducted on variations in colonial educational infrastructure for example, for which trends for creative expression infrastructure seem to concur. Some sources do include Emma Eolukai-Wanambwa’s study into arts education infrastructures in East Africa, or broader studies of imperial cultural infrastructures such as that of Elise Huillery (2009) or even Walter Rodney (1973). See Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa, “Margaret Trowell’s School of Art or How to Keep the Children’s Work Really African.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Race and the Arts in Education, edited by A. Kraehe, R. Gaztambide-Fernández and II. B. Carpenter (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018); Elise Huillery. “History Matters: The Long-Term Impact of Colonial Public Investments in French West Africa.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Vol. 1, N. 2 (2009); Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Dar-Es-Salaam: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications, 1973).

[6] Dludlu, Maswati. Personal Interview. 11 April 2017; Mpfunya, Farai. Personal Interview. 6 April 2017; Andrew Mulenga. Germinating in the cracks: the identity of contemporary Zambian art. Zambia – 72 peoples form a state – insights in a post-colonial society (Wuppertal: University of Wuppertal, 2016); Raphael Chikukwa, Returning to the early conversations. Mawonero / Umbono: Insights on Art in Zimbabwe (Berlin: Kerber Verlag, 2016)

[7] Chikukwa, Returning to the Early Conversations; Esme Berman, Art & Artists of South Africa: An Illustrated Biographical Dictionary and Historical Survey of Painters, Sculptors & Graphic Artists Since 1875 (Cape Town: Southern Book Publishers, 1993).

[8] Joane Pim, Beauty is Necessary – Preservation or Creation of the Landscape (Cape Town: Purnell, 1971); David Coplan, In Township Tonight: Three Centuries of South African Black City Music and Theatre (Johannesburg: Jacana, 2007).

[9] Lance Larkin, Following the Stone: Zimbabwean Sculptors Carving A Place in 21st Century Art Worlds (PhD Dissertation (Illinois: University of Illinois, 2014); Doreen Sibanda, Main drivers for the growth and development of sculpture movements in Zimbabwe. Mawonero / Umbono: Insights on Art in Zimbabwe (Berlin: Kerber Verlag, 2016).

[10] Coplan, In Township Tonight.

[11] Ntone Edjabe, ed. Festac 77 (Cape Town: Chimurenga and Afterall Books, 2019).

[12] UNCTAD, Strengthening the Creative industries for Development in Mozambique. Strengthening the Creative Industries in Five Selected African, Caribbean and Pacific Countries through Employment and Trade Expansion (Geneva: United Nations, 2011); Joseph Gaylard, “The craft industry in South Africa: a review of ten years of democracy.” African Arts, vol. 37, no. 4 (2004).

[13] UNCTAD, Strengthening the Creative industries for Development in Zambia. Strengthening the Creative Industries in Five Selected African, Caribbean and Pacific Countries through Employment and Trade Expansion(Geneva: United Nations, 2011); Melissa Everleigh. ARTS & CULTURE Stakeholder Research: Funding Analysis: Modes of Engagement (Harare: Nhimbe Trust/ Pamberi Trust, 2013).

[14] Arterial Network, Artwatch Africa Review (Cape Town: Arterial Network, 2014).

[15] Dludlu, Maswati. Personal Interview. 11 April 2017

[16] Mpfunya, Farai. Personal Interview. 6 April 2017

[17] Koyo Kouoh, Artistic Education in Africa. Condition Report Series (Dakar: Raw Material Company, 2014). Nicola Lauré Al-Samurai, Creating Spaces. Non-formal Art/s Education and Vocational Training for Artists in Africa Between Cultural Policies and Cultural Funding (Nairobi: Contact Zones NRB Text Goethe-Institut Kenya and Native Intelligence, 2014).

[18] Simone, “People as Infrastructure”, 409.

[19] Simone, “People as Infrastructure”, 428.

[20] Pat Oyelola and P. Chike Dike, The Zaria Art Society: a new consciousness (Lagos: National Gallery of Art, Nigeria, 1998).

[21] Koyo Kouoh, WORD! WORD? WORD! Issa Samb and the Undecipherable Form. Verksted 15 (Dakar: Raw Material Company, Office for Contemporary Art Norway and Sternberg Press, 2013).

[22] Molemo Moiloa, “Notes on Inheritance: threads of socially oriented arts organizing in Johannesburg” in Fadzai Muchemwa (ed.) Curating Johannesburg: Restless, under siege, in transition (Johannesburg: Bag Factory, 2019).

[23] Thami Mnyele, Observations on the state of the contemporary visual arts in South Africa (Gaborone: Medu, 1984), p.27.

[24] Ferdiansyah Thajib. “Introduction. Holopis Kuntul Baris: The Work of Art in the Age of Manifestly Mechanical Collaboration”, Discipline No.4, Spring/Summer 2015, p.5.

[25] Khumalo, Nathi. Personal Discussion. 28 October 2019

[26] Dumse, Lerato. Personal Interview. 1 December 2016

[27] Dludlu, Maswati. Personal Interview. 11 April 2017.

[28] Mulenga, Andrew. Personal Interview. 7 March 2017

[29] Kaleni Kollective (eds). Owela: The Future of Work. Vol 1. Kaleni Kollective, 2019, Windhoek

Kollective, p.1.

[30] Mushaandja, Nashilongweshipwe. Teacher Don’t Teach Me Nonsense, Teach me Owela: A Journal Entry. Owela: The Future of Work. Vol.1 Kaleni Kollective, 2019, Windhoek, p.23.

[31] Trixie Munyama, Selfcare. Organizing: collective, collaborative organizing in Southern Africa. Johannesburg: VANSA, 2019), p.48.

[32] Seganabeng, Legodile. Personal Interview. 27 October 2016

[33] Eugene Paramoer, Working with those who are present. Organizing: collective, collaborative organizing in Southern Africa (Johannesburg: VANSA, 2019).

[34] Eugene Paramoer, Working with those who are present. Organizing: collective, collaborative organizing in Southern Africa (Johannesburg: VANSA, 2019).

[35] Chisuvi, Biko Mutsaurwa. Personal Interview. 4 November 2016

[36] Nuraini Juliastuti, Wok the Rock & Co.: Making Sense of Friendship in Yogyakarta’s Art Scene. Holopis Kuntul Baris: The Work of Art in the Age of Manifestly Mechanical Collaboration, Discipline No.4, Spring/Summer 2015, p. 42.

[37] In the discussion on genders role in organizing, I also discuss the significant limitations women organizers have identified, and the number of collectives actively seeking strategies to shift patriarchal practices in their collectives and the arts field at large. Molemo Moiloa, Organising: collective, collaborative organizing in Southern Africa(Johannesburg: VANSA, 2019).