On the Fashion Parade 2017: Pushing Back Against the Shrinking Deliberative Space in Uganda

Angelo Kakande

Funeral Dress is a band formed in Belgium in 1985. Not much of its music makes its way to Uganda. But I listened to their song Party Political Bullshit (2000) from their album of the same name when I was pursuing my doctoral studies at the University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa) and was becoming very cynical about politicians in Uganda. In this song, Funeral Dress criticizes politicians for being selfish, “using people for personal fun,” and “telling us lies”.[1] In my Ph.D. thesis, Contemporary Art in Uganda: A Nexus Between Art and Politics (2008), which focuses on the work of several artists, I argued that the contention that politicians are telling lies had shaped visual expression in Uganda. In my dissertation I did not specifically address the issue of political violence in Uganda, which can silence citizens and, as a result, affect an artist’s willingness and ability to speak out. I engage this issue in this essay. I observe that, as a postcolonial state, Uganda has been characterized by violent repression and hopelessness caused by the failure of the country’s elites to reach a political consensus, and their decision, instead, to resort to the use of brute force in order to resolve the political questions of the day.[2] In a situation in which successive governments have orchestrated such brutality to instill fear, suppress dissent, and impose silence, what alternative strategies have Ugandans used to push back? In what ways has this pushback been culturally productive? How have artists raised their voices, and innovatively explored their skepticism, cynicism, activism, self-expression, non-violence and commitment to socio-political causes, using a medium which the agents of coercion could neither predict nor suppress?

In this essay, I respond to the above questions while examining the Fashion Parade 2017 (and its theme of “beyond fashion”) as a political site through which some students of the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Art, at Makerere University, used drawings, dress and catwalk performances to express dissent and launch an alternative (and less confrontational) defense for the rule of law and human rights. The essay does not cover the entire breadth and depth of the concept of “art and human rights” in Uganda. Rather, it is exploratory; it involves the analysis of particular visual experiments that have become sites for less confrontational forms of political activism and dissent. This analysis is threefold. First, I briefly introduce Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Art at Makerere University in which the Fashion Parade 2017 was conceived and hosted. Secondly, I trace the origins of political violence in Uganda. In the process, I build an understanding of the violent histories which have shaped the decisions, strategies, and consciousness of most artists in Uganda. I bring to the fore some symbols and symbolisms which artists appropriated through works they presented in the Fashion Parade 2017. Thirdly, I demonstrate that by responding to and being in solidarity with the Togikwatako political campaign (which I explain in a moment), Ugandan students at Makerere University placed dress at the centre of the debate on Uganda’s “politics of violence”; apparel became a site for dissent and a voice for the voiceless who have refused to cower to brutality.

To establish some context for this research, I interviewed key informants and accessed the available archives—including the Hansards of the Parliament of Uganda, the print and electronic media, case law, song and other forms of popular culture.[3] Although it is eclectic, this approach to the debate on Uganda’s visual culture (and art history) is firmly rooted in all my areas of expertise as an artist, art historian and lawyer. It is productive in the sense that it allows me to access resources which help me to deal with the complex public space of Uganda as I retrace the shared contours between politics and art. It has helped me, in this essay, to retrace the links between a political campaign codenamed the Togikwatako campaign, which became a matter of political protest, public policy and law, and the Fashion Parade 2017 at Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Art.

Setting the Scene: Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Art at Makerere University

The Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Art (also called MTSIFA) is named after the British artist and art educator Margaret Katherine Trowell, who came to Uganda during the 1930s. Trowell had two missions: first, she wanted “to develop modern African Art rooted as far as possible in African tradition and secondly to encourage students to be genuinely creative.”[4] To fulfil her mission, she laid a strong foundation for formal art education at Makerere College (currently Makerere University). Trowell returned to her native England in 1958; her place was taken by other European and African instructors. However, she left behind an art school which has since produced students who, in addition to using their traditions as referents from which to develop art and place it in the global art circuit, have invested their creativity in projects that contribute to political debates in Uganda.[5] It is here that the Fashion Parade 2017 was hosted on November 17, 2017 in the Makerere Art Gallery (also called Institute of Heritage Conservation and Research).

Uganda: A Story of Lost Hope and Perpetual Political Violence

Uganda is a small, landlocked African nation estimated to be 241,038 square kilometres. It is bordered by the Republic of Southern Sudan to the north, Kenya to the east, Tanzania to the south, Rwanda to the south-west and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to the west. Created as Britain’s “sphere of influence” during the late-nineteenth century, Uganda became an independent nation-state on October 9, 1962 amidst high expectations: “people felt that their material welfare and their human dignity would be enhanced.”[6] These are the high expectations symbolized in the Independence Monument (1962): a sculpture by artist Gregory Maloba which depicts a towering mother figure hoisting an ecstatic child into the air (Fig. 1) to celebrate the birth of Uganda as a postcolonial state.

And yet a concern for many (including the artists who participated in the Fashion Parade 2017), is that the ideals of access to material welfare and the enjoyment of human dignity are yet to be realized in Uganda. By 1964 the country was on the path to violence. Constitutional order, the rule of law and respect for civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights were abandoned. The country descended into perpetual violence marked by lack of freedom, anarchy, suffering, bloodshed, economic meltdown, misrule, dictatorship, hopelessness and senseless destruction of life and property. This is the violence reiterated in the stillbirth (Fig. 2) at the center of Mathias Kyazze Muwonge’s painting titled Misfortune (1985).

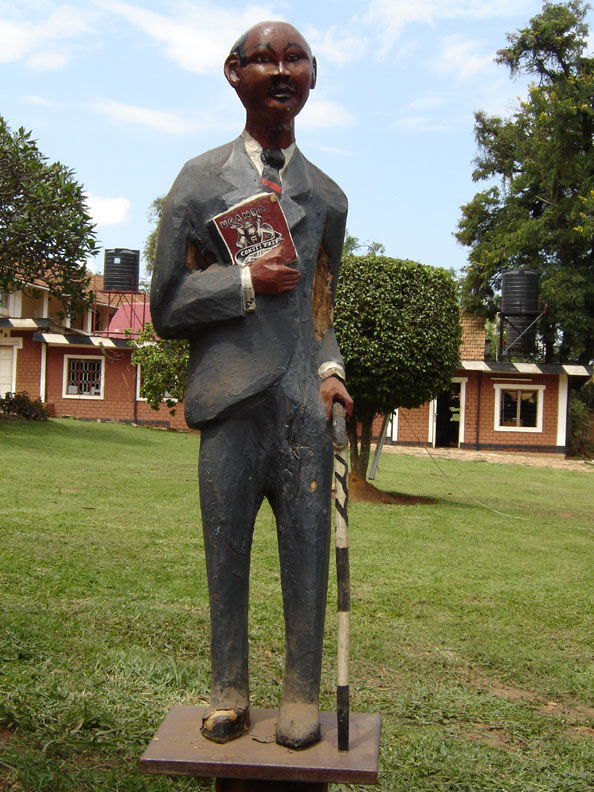

It is against this backdrop that the National Resistance Movement (the NRM) and its armed wing, the National Resistance Army (the NRA), launched a five-year rebellion (which ended in 1986) in order to restore political sanity. Many expected a fundamental change in 1986 when the ruling National Resistance Movement initially took the power it has now monopolized for the last thirty-four years. This was because while being sworn in as the new President on January 26, 1986, Yoweri Museveni declared that: “No one should think that what is happening today is a mere change of guard; it is a fundamental change in the politics of our country.” Consistent with this declaration, the NRM unfolded a raft of radical reforms including the drafting of a new constitution. To celebrate the political reforms, and the new constitution itself, an anonymous artist sculpted President Museveni holding the new constitution close to his chest and wielding a stick symbolising stewardship (Fig 3). Portrayed this way, President Museveni became the very embodiment of the making of the new constitution, rule of law, and unprecedented political sanity in Uganda.

And yet the artist-activists who participated in the Fashion Parade 2017 (and whose projects we will turn to in a moment) argued that all is not well. Their scepticism can be traced back to the fact that they were born during the nineties. They have no memory of the mayhem which Muwonge (Fig. 2), Tumwine, and the anonymous artist (Fig. 3) experienced. However, their concerns have been widely shared across generations and can be validated. For example, in 2001 President Museveni enjoyed a great deal of local and international support.[9] That notwithstanding, he was elected through a process marred by violence and intimidation unleashed by members of the military and paramilitary forces sympathetic to him and the ruling NRM party. In the case of Besigye Kiiza v. Museveni Yoweri Kaguta and Another (Election Petition No.1 of 2001), the Supreme Court of Uganda agreed that the actions of these armed outfits were illegal; they infringed on people’s civil and political rights. However, this decision was not like the later decision of the Supreme Court of neighboring Kenya in the case of Raila Odinga & 5 others v. Independent Electoral & Boundaries Commission & 3 others (Election Petition No. 3, 4 & 5 of 2013) which annulled a presidential election when it found evidence of violence, among other irregularities, in Kenya’s 2017 presidential elections. It was also not like the decisions of Courts in Malawi which annulled a presidential election characterized by violence among other irregularities. This is because the Supreme Court of Uganda did not annul the 2001 election as it should have. As a result, it allowed the ruling party (and President Museveni) to benefit from a flawed and violent election; it set the stage for an equally flawed and violent election in 2005 which was also challenged, but never annulled, by the same court.

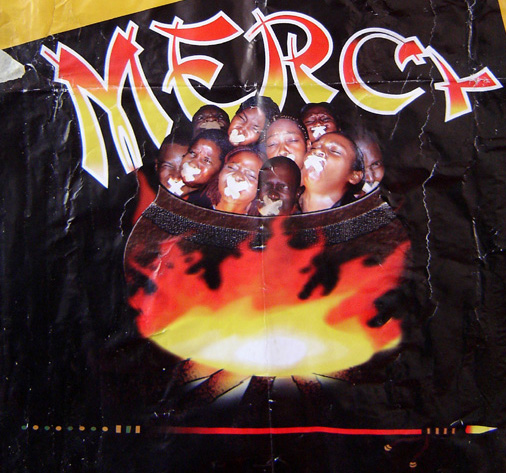

Alex Mukulu’s play, Akattambwa (2005), demonstrated that the violent 2005 election had brutalized the population. The poster on which the play was advertised (Fig. 4), shows a group of people packed in a pot. A fire rages below, consuming the pot and threatening to dissolve the crowd of people, representing the people of Uganda, packed into it. The writing is on the wall: people, portrayed as victims, need “mercy”. They can express their anguish through gestures. However, they cannot openly express their trauma, agony, and fear because their mouths are sealed with adhesive tape. Decisively, Mukulu radicalized the traditional pot by turning it into a site for speaking out against torture and inhumane and degrading treatment, all of which are prohibited by the Constitution of Uganda and international law. In a moment, we will see a return to this strategy in the Fashion Parade 2017.

I want to point out that the violence literally represented in Mukulu’s poster has been institutionalized through draconian legislation, especially the Public Order Management Act (2013). Security agencies conveniently use this legislation to violently suppress dissent and disrupt political gatherings, processions, and discussions, with the exception of those organised by President Museveni and the supporters of the ruling NRM. These are the political machinations that have turned Uganda into a hybrid state in which violence and intimidation are routinely used to organize regular elections.[10] Because of this, the space available for freedom of speech in Uganda has become severely constricted.

Betty Aol Ocan agrees. She is the Leader of Opposition in the Parliament of Uganda (commonly called the LoP).[11] The LoP is a powerful position in the Parliament of Uganda, equal to the position of a Cabinet Minister.[12] He/she handles important tasks in the administration of the parliamentary business to “keep government in check.” As such, and in accordance with the law, Ocan monitors all government policies.[13] In the performance of this function, on January 7, 2019 Ocan assessed the space available for Ugandans to debate public policy and hold leaders accountable. She observed that “in Uganda, this space is alarmingly shrinking and becoming a monopoly of the ruling NRM party.”[14] Of particular interest for this essay are the ways in which such shrinking space, which is poignantly visualized in Mukulu’s poster, has shaped subtle forms of resistance that the repressive state can neither recognize nor constrain. In the next segment, I will return to this question as I assess the Fashion Parade 2017, which art students at Makerere University turned into a site for resistance and activism by demonstrating that fabric and color can be deployed for political action and dissent.[15]

The Fashion Parade 2017: Silent Resistance, Political Voices away from Violence

On November 17, 2017, the Makerere Art Gallery hosted the MTSIFA Fashion Parade 2017 under the theme Beyond Fashion (2017). Sarah Nakisanze, an instructor for fashion design at MTSIFA, curated it and invited former and current students of MTSIFA to showcase their apparel. The show went beyond the curriculum as artists were invited to explore their individual sub-themes and ideas outside the syllabus. In response, participants drew from a wide range of issues, forms and materials to design and accessorize their garments, including the gendered roles of women in society, environmental activism, culture and traditions, health and reproductive rights, flora, fauna and the Togikwatako campaign which is important for the rest of this essay. Togikwatako is a Luganda word meaning “thou shall not touch that object”. It became the central theme for a wave of activities that challenged the amendment of Article 102 of Uganda’s constitution. This Article provides for the “qualifications of the President.” Under Article 102(b) a “person is not qualified for election as President unless that person is . . . not less than thirty-five years and not more than seventy-five years of age”. President Museveni was believed to be 73 years old in 2018; as such he would have been ineligible to stand in the presidential election slated to take place in February 2021 under Article 102(b).

In a move intended to benefit him and allow him to “rule for life,” the Parliament of Uganda passed Constitution (Amendment) Act (No. 1) of 2018 removing Article 102(b) from the Constitution. This was done in the midst of chaotic scenes involving the military beating Members of Parliament opposed to the amendment. Some were hospitalized; others were taken to jail and denied access to their families and legal representation. The amendment, and the violence that came with it, attracted widespread international and local criticism which shaped the Togikwatako campaign. This campaign started in Uganda before it spread to other countries in Africa and beyond. Most importantly for this essay, it informed popular culture especially through the print and electronic media, theatre and song. But if Stuart Hall believed that “popular culture is the site at which everyday struggles between dominant and subordinate groups are fought, won and lost,” then the Togikwatako campaign allows us to see the strategies Uganda’s subordinate individuals and groups developed to continue fighting while avoiding losses.[16]

For example, in his song Togikwatako (2017), Robert Kyagulanyi, a.k.a Bobi Wine, reminded Ugandans of the violent history that shaped their country, which occurred due to a lack of consensus. He proposed that Article 102(b) of the constitution was arrived at by consensus, and that its removal would disrupt such consensus as well as eliminate the last protection against the return to dictatorship and bloodshed witnessed in the sixties, seventies, and eighties. His notion of consensus was widely shared among those opposed to the removal of Article 102(b). Justice Benjamin Odoki served as the Chief Justice of Uganda from 2001 to 2013. He headed the process by which Article 102(b) was included in the 1995 Constitution of Uganda. In his book titled The Search for A National Consensus: The Making of the 1995 Constitution (2004) he too referred to the need for such consensus and how it was achieved during the constitution-making process. Unfortunately, Kyagulanyi was brutally silenced; he narrowly survived an attack that claimed the life of his driver, Kawuma, on August 13, 2018. His ability to advance his musical career has been permanently frustrated, through an official government ban on his music. During an interview on the BBC’s News Day program on October 18, 2019, President Museveni explained the rationale and policy behind the ban thusly: Kyagulanyi cannot be allowed to make money from his music because he is an “enemy of progress in Uganda.” [17]

The courts have been unwilling to help the singer. For instance, in the case of Kyagulanyi T/a Bobi Wine v, Kampala Metropolitan Police Commander & Another (2019), the continuous ban on Kyagulanyi’s music concerts was challenged before the High Court of Uganda.[18] Lady Justice Henrietta Wolayo heard the case and ruled that “music shows organized for the sole purpose of entertainment and revelling do not fall under the regulation of the Public Order Management Act unless they are organized for the purpose of expressing views on matters of public interest, or spontaneously become such.” In other words, the judge confirmed that the government has powers to prohibit the use of music as a medium for challenging the government on matters of public interest; she contended that artistic production (and thus fashion parades) cannot be used for political mobilization or the expression of dissent.

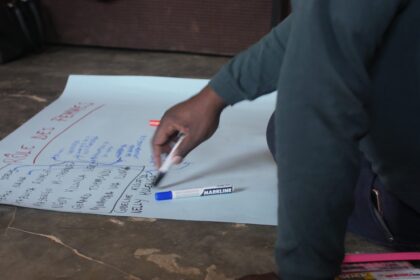

Concerned about the risks of confronting the police, and of a weak judiciary unable to defend them against the police state, many Ugandans turned to what Peter Levine called the “strategies of nonviolent confrontation,” especially visual expression.[19] It is interesting to examine how this strategy worked at Makerere University. First, some university student activists, who are not professional graffitists themselves, used stencils and spray to produce graffitied statements (fig. 5) in which they expressed dissent without attracting the wrath of security operatives. They placed political graffiti in Makerere University, an elitist space where graffiti is generally shunned as an irreverent form of visual expression and a physical display of unethical conduct that must be severely punished.[20] These forms of graffiti allow us to access the innovative ways through which social engagement and art can be intertwined to challenge what John Gastil called the “ . . . persistent intolerance, and infringements on basic human rights” in Uganda today. [21] Secondly, other student activists, who participated in the Fashion Parade 2017, aligned their apparel with the Togikwatako campaign. This apparel resonated with the political context of the campaign for the following two reasons: First, they demonstrated that the students who aligned their apparel with the Togikwatako campaign acted in solidarity with the popular resistance to the amendment of the constitution of Uganda. Thus, unlike the Different but One 22 Exhibition (2018) hosted in the same space to present artworks the staffers at MTSIFA had produced in 2017, the fashion parade was overtly political.[22] I argue that coming two months after the parade, the Different but One 22 Exhibition was far removed from the urgent political realities of the day which informed the Togikwatako campaign. Secondly, the apparel presented in the parade, and the claims the students made for it, help us to understand the ways in which the heated debate on the removal of article 102(b) from the constitution informed the teaching, learning and production of art and design at Makerere University. Let me demonstrate my claim.

Brenda Namazzi was a student of MTSIFA when she participated in the Fashion Parade 2017.[23] She presented apparel based on the theme “I love Uganda”. She designed and accessorized her garments with a combination of traditional and modern objects (and ideas) to “produce a statement”. In her accompanying essay, Namazzi explained the statement behind her dress arguing that: “Uganda defines our souls and people can feel it; [they cannot forget] how colorful she is, natural green everywhere; black, yellow and red on the Uganda flag . . . the pearl of Africa, Uganda zaabu.” I would argue that Namazzi’s project invites us to examine four interesting issues. To begin with, in her text, she reiterated the state-sponsored promotional campaign circulated by the government-owned Bukedde TV, to market Uganda as a good destination for tourists under the theme Uganda Zaabu (translated: Uganda the pearl of Africa). Secondly, Namazzi reiterated the characterization of Uganda as an exotic country. This characterization has a history going back to Henry Morton Stanley (the American explorer and journalist), who came to Uganda in 1872 and Winston Churchill (the British Premier), who visited Uganda in 1908. These two men popularized the notion that “Uganda is the Pearl of Africa,” to which Namazzi linked her project.

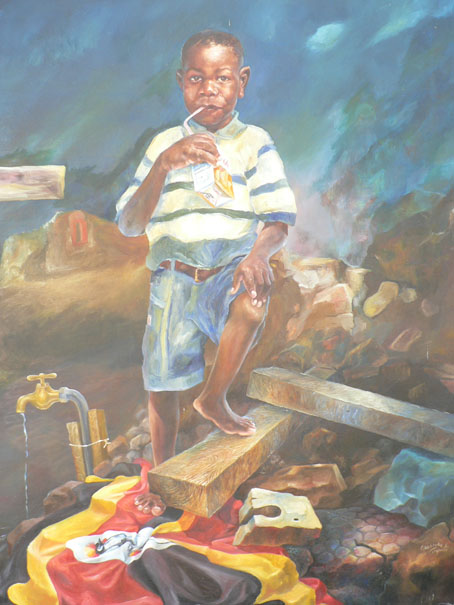

The third issue comes from the Ugandan flag which Namazzi refers to as “ black, yellow and red on the Uganda flag”. She does not literally reproduce the flag in her three-piece wearable product, composed of a red blouse, a short yellow skirt, a sleeveless overcoat made out of bark cloth, and accessorized with a basket, sisal materials and cowrie shells (Fig. 6). Her use of the flag differs from that of her teacher, Stephen Gwoktcho, who used the Uganda flag in his painting (Fig. 7) titled Stepping Stone (2005), to critique the venality of the NRM. [24] This is because she does not use the national flag subversively. Together, with the Coat of Arms (designed by a British art instructor at Makerere University named Cecil Todd), and the national anthem (composed by George Wilberforce Kakoma), the Ugandan flag evokes a strong sense of unity, patriotism, and nationalism. Grace Ibingira designed it. It was unveiled on October 9, 1962 when it was widely discussed in the press that the flag’s black, yellow, and red horizontal stripes, and a centered, crested crane (the national bird), represent togetherness, freedom, liberty, hard work, neighborliness, peace and friendship. For these reasons the flag is jealously protected under Articles 8 and 17 of the Constitution of Uganda and The National Flag and Armorial Ensigns Act which penalizes the abuse and any “unauthorized use of the flag”. [25] It is probable that Namazzi had some (or all) of these issues in mind as she did her work. However, as indicated earlier, the ideals of togetherness, freedom, liberty, hard work, neighborliness, peace and friendship have never been fully realized in Uganda. This would suggest that Namazzi’s use of the flag was clearly not critical, but simply reinforced the dominant ideology of the NRM.

Fourthly, Namazzi was born in the 1990s. In 2017 Robert Kyagulanyi and Nubian Li released the song, Uganda Zukuka, in which they called on Ugandans who, like Namazzi, were born after October 9, 1962 (the day a beautiful nation was “born . . . with a promise of democracy” which, as I have indicated above, was never fulfilled), not to believe in the vision of a Uganda propagated by old “leaders who do not think about the next generation; all they think about is the next elections.”[27] They argued, through their song, that although successive postcolonial governments have used excessive military force to cling to power, this police state can be defeated by the young generation. The two musicians called on the youth to “wake up”, collectively “defend the future” and generate local solutions to heal the wounds created by the country’s rugged postcolonial history. The song was understood to be part of the Togikwatako campaign. Namazzi was aware of this call. She, however, did not respond to it in her project since, as indicated above, her use of the flag in the Fashion Parade lacked any critical component, and simply reinforced the idea that Uganda was a happy, peaceful country awaiting tourists.

We encounter a revealing contrast in the work produced by Namazzi’s classmate, Sanyu Loyce Naigino. Naigino listened to Uganda Zukuka (2017) and Kyagulanyi’s other song, Freedom (2017), which was played during an art history lecture she attended at MTSIFA. In addition, she watched what she called the “Togikwatako animations posted on Facebook.” She confirmed during our interview that the songs, the lecture, and wider political debate at the time informed her consciousness and decision to oppose the removal of Article 102(b) from the constitution. But Naigino had a specific political issue behind her dress. She explains that having been born in 1997, she was concerned about the “youths whose future is not bright” and who “lacked freedom” given the current political environment. She, however, is “an introvert” and as such could not “openly participate in the Togikwatako campaign” through demonstrations, processions, and political gatherings. Instead, she used her “fashion project” as a device to challenge the policy and decision to change the constitution. Under her theme, “the question of Uganda’s independence,” Naigino re-examined Uganda’s history since independence. In an accompanying essay, she raised the following vexed question to provide some context for her project: “We say we have independence. But are we really free? . . . we are betrayed by our own” (my emphasis). Interestingly, Naigino’s sense of betrayal was productive, allowing her to appropriate the national flag to produce a long, sleeveless dress. Now, it is not uncommon for Ugandans to wear clothing made out of the colors of the national flag. For example, the uniforms of all the national sports teams reflect the colors of the national flag. However, Naigino went beyond blind patriotism to express discontent. She used ropes and nets, which rarely function as beauty accessories. She dyed them in the national colors of black, yellow and red and used them to fasten, and support, the sleeveless dress around the shoulders of the model. She also tied the ropes around the model’s neck and wove similar ropes together into a net which she wrapped loosely around the model’s body from the waist downwards.

In our interview, Naigino explained that the symbolism of the rope wrapping in her work came from the sculpture titled Independence Monument (Fig.1) in which Gregory Maloba used the symbolism of [un]wrapping to imagine and represent a new postcolonial state in Uganda. This may be so. I, however, believe that Naigino’s use of artistic expression to question Uganda’s postcolonial independence does not come directly from Maloba’s Independence Monument. Instead, her theme harkens back to the exhibition titled the After Independence… So What; Now What? which was hosted at Makerere Gallery in November 2009. It was a group show in which many artists, including Naigino’s teacher Mathias Kyazze Muwonge, re-examined the forty-seven years of Ugandan independence. Muwonge presented a headless, and limbless body of a woman placed in an open coffin. Her body is draped in a white t-shirt decorated with the Ugandan flag (Fig. 8). Muwonge drew on traditional and Western funeral rites. To reveal the political context behind his work, Muwonge wrote a statement, titled “The Will,” in which he evaluated the forty-seven years of Uganda’s existence as a postcolonial nation-state. He reminded his audience that in 1962 Uganda inherited a colonial, capitalistic logic under which different ethnic groups were lumped together to form a “productive total[ity].” However, no economic progress and unity were achieved. This suggests the kind of political scepticism behind Naigino’s project. As such, although the [un]wrapping in her work may be traced back to Maloba’s Independence Monument (to which I referred earlier), her use of ropes (wrought into a kind of a net) to fasten the body of a woman suggests restraint and coercion. In other words, it can be argued that, unlike her peer Namazzi who does not question state-sponsored nationalism and patriotism, Naigino questions the health of the nation-state. She pays attention to the (recurrent) loss of liberty in her country. She addresses the political concerns of her time. However, not like her teacher Muwonge who uses a limbless dead woman, Naigino does not return to the thematic morbidity and mortality of the seventies and eighties (also seen in Godfrey Banadda in his Last Hope (1983) and Allan Birabi in his Luwero Triangle (1985), among others) to represent political reality. Instead, she presents a youthful model who briskly walks towards her youthful audience thus breathing a sense of life into her political statement. (I say youthful audience here because the majority of those who attended the Fashion Parade 2017 were university students.).

On the other hand, although Naigino’s choice of a middle class, female, college student as a model suited her university audience, it is important to note that there are certain stereotypes which may hinder the relevance of her project to issues affecting many Ugandans outside Makerere university. For instance, the wider perception circulated in popular culture (through art, music, drama and the print and electronic media) is that female university students are slothful, gold diggers. Consistent with this construction is the notion that female college graduates are not “wife material”; they are unsuitable for marriage to any heterosexual male in search of the ideal woman characterized, in the Daily Monitor published on April 24, 2020, as “a great cook, a great mother, happy to play the role of number two to whichever man finds her worthy enough of his ring, warts and all. And of course she doesn’t laugh too loudly or drink beer.” In her song I am not a golddiger Jackie Chandiru, a graduate of MTSIFA, attempted to unsettle this construction confirming that college women graduates are pushing back against it. However, commonly called “bukampasa” (translated: the young, female university students/graduates), college women are not considered to be examples of the ideal woman who is wife material. This is because there is a widely held view that college women, including Naigino and her model, are greedy; they demand lifestyles, and material conditions, that are far removed from the lives of the ideal (generally poor) selfless, rural, hardworking, motherly, wife material women who constitute the bulk of Uganda’s rural population. In their song Ngenda mu Kyalo (translated as “I am going back to the village to find a respectful wife” 1990) Kadds Band celebrated this rural woman as wife material. Opolot William Okitoi gave visual expression to her selflessness in Corruption (1990) a painting in which the artist questioned the morality of the self-serving, male members of the ruling NRM party (whom President Museveni calls “the NRM-cadres”) and critiqued the way they had co-opted the educated women to exploit the rural masses. More so, that the Fashion Parade 2017 was hosted in an elite space and community at Makerere University (also called the Ivory Tower) would further alienate the event, and its participants, from the wider interests of the communities outside whose concerns are largely about bread and butter.

I am not prepared to wholly dismiss the above criticism. I would however strongly argue that Naigino’s choice of a college woman functioned in ways that were linked to issues outside of the University as well. For example, the model’s coiffure is plaited into thin braids and tied backward to expose her face with tears rolling down her eyes (Fig. 9). Naigino asserted during our interview that through “silence the model spoke whatever [Naigino] wanted to speak about,” (i.e., the political violence in the country at the time). This violence affected the lives and civil liberties of many outside Makerere University as much as it affected Naigino, her model and the rest of the university community. Most interestingly, as this explanation suggests, Naigino used her dress to speak back to the agents of the state who abused the fundamental human rights of many Ugandans. By extension she cast doubt on the country’s future. I would argue that in this sense, she gave visual expression to the collective silence of the numerous victims of political violence and the crimes committed by the security forces. I concede that although she can be credited for creatively using fashion to speak back non-violently, her use of the woman’s body in this enterprise could be problematic in a country where violence against women is on the increase in spite of the laws put in place to end it. I, however, maintain that although valid, such criticism does not undermine Naigino’s contribution to the discussion of the day since her Question of Uganda’s Independence was a veiled statement directed against those who have routinely violated the rights of Ugandans. This is the context in which the garments presented by her classmates Charles Ssembatya, Mike Ssebaale, and Vivian Naume Logose, whose projects I turn to next, must be understood.

Vivian Naume Logose is more politically active than her counterparts. This is because she is a member of the Uganda Young Democrats (UYD), and has been since 2016. During our interview, she expressed hope that she will one day “become a Member of Parliament representing her home District Pallisa” in Eastern Uganda. This is not unusual. The Parliament of Uganda has a number of legislators who graduated from MTSIFA; others are serving in other organs of the state. What is important to note though, is that Logose’s UYD is a group of young political activists pursuing courses at Uganda’s tertiary institutions. Logose belongs to the Makerere University Chapter which has nurtured several politicians, including Members of Parliament. She followed the discussion on the removal of the age-limit clause from the constitution of Uganda, and thus the Togikwatako campaign, through the UYD, discussion with peers, music (like Kyagulanyi’s songs), social media, and print and electronic media. Like Naigino’s project discussed earlier, Logose used a female model, albeit not one in tears. She is draped her model in a short, red skirt with an irregular hem, accessorized with long, sharp, silver spikes. The skirt is accompanied by a simple wrap for the breasts which is accentuated by loose, hanging, red, yellow, and black cloth, reflecting the colors of the national flag. Similar cloths were added to the hat, which, together with the necklace, were accessorized with spikes to give the wearer a sort of punk style (Fig. 10 and 11).

Fearing for her personal safety, Logose did not take part in any rallies (or processions and demonstrations) organized in or outside of Makerere University in solidarity with the campaign against the constitutional amendments of 2017. Instead, she used the Fashion Parade: “it was the safest way to speak out [publicly] in the face of those in power who have all the guns. The best way for me to showcase my anger was through fashion,” she said during our interview while linking her Togikwatako project to the Togikwatako campaign.

Next is Charles Ssembatya who, in his Togikwatako Story (2017), appropriated the red-yellow-black colors of the Ugandan flag to decorate his predominantly white casual wear. During our interview, he argued that he targeted a youthful, male audience. This would be in line with the curriculum at MTSIFA which often requires that students indicate the market segment they are targeting. It also confirms that like Kyagulanyi and Nubian Li in their Togikwatako Song, which I referred to earlier, Ssembatya was using his Togikwatako Story to speak to the younger generation while contributing to alternative mediums of expression through which the youth, like him, could speak back to brute power. His decision to introduce chains and padlocks into his design would suggest that he is aware of the influence of hip-hop culture on the fashion trends in Uganda. However, these accessories also function in two other related ways that merit our attention. First, they project an image of the body of the male subject wrapped in chains and (pad)locked, without being restrained. Secondly, in this instance, the chains and locks gained new symbolic and functional meaning; Ssembatya chained his project to the struggle to defend constitutionalism in Uganda. In an accompanying essay pinned on the wall during the Fashion exhibition which was held alongside the Fashion Parade, he confirmed this claim. He explained that he got [t]his “inspiration from what [was] taking place in Uganda.”[28] This assertion, together with the title of the project, confirms that his garment was historical and political. This statement confirms that Ssembatya responded to the broader resistance to the removal of the age limit clause from the constitution of Uganda.

Mike Ssebaale’s Togikwatako (2017) also merits mention. During our interview, Ssebaale explained that he based his work on the belief that a constitution is the basis for a contract between the state and the people. This is because “constitutions are very important as they provide the guiding principles necessary for the running of the state,” as he said. Taking this as a principle, he refused to support the “unpopular decision” to delete Article 102(b) from the laws of Uganda so as to “keep President Museveni in power.” He admits that he had heard some of the anti-NRM propaganda which the opposition politicians spread through the print and electronic media especially through social media platforms (like Twitter, Whatsapp, Instagram, Facebook, etc). Many Ugandans use these same platforms to share information (including propaganda) and push back against the brutality of the security agencies. He, however, argues that his work is not mere propaganda. He critically evaluated the situation in the country and held regular discussions with peers before he consciously took a position regarding which side of the debate to align himself and his project with. He could not participate in the few public rallies that occurred, all of which were disrupted by the security agencies using the Public Order Management Act, to which I referred earlier. This was a draconian law enacted in 2013 to limit space for political mobilization in Uganda; it was successfully challenged before the Constitutional Court of Uganda in the case of Human Rights Network and four others v Attorney General which was decided in March 2020. Ssebaale was aware of this case; he followed the Court proceedings through the electronic and print media. He, however, had a personal experience which immediately influenced his decision to do this work. He vividly remembered an incident in which a policeman attacked him for wearing a “red bandana” which was linked to the Togikwatako campaign. He was lucky not to be arrested. However, being targeted by the military exacerbated his apprehension. He concluded that the public space had shrunk; his freedom of expression was under serious threat.

To confront this threat, Ssebaale decided to use his garment, and the catwalk, to “express everything” he wanted. This is how he explained his position during our interview: “I used the fashion parade because this nation is not safe; I used my work to avoid being killed.” In addition, he wrote what he called a “manifesto” in which he laid out what, in his view, should be the priorities of young people in Uganda. He pinned it on the wall during the Fashion Exhibition; I reproduce it hereunder:

MY STORY BEHIND THE DESIGN

What am I saying? You are the master of your life, your choices, your plans and mainly your future. Comfort is a very beautiful place but nothing ever grows there. If you need to change your life, you must embrace the tides that come with it. You reap what you sow. Stand in the face of your mourning self and accept to evolve.

Remember! The twenties are for planning, the thirties are for investing, the forties are for consolidating WITHIN THE NATION WHICH YOU ARE PART OF.

Your strides are too long for this comfort but the truth remains, THEIR VISION IS BLURRED.

-TOGIKWATAKO-

SSEBAALE MIKE (emphasis in the original)

To give visual expression to his manifesto, Ssebaale produced a three-piece garment: a very short blouse which left most of the wearer’s body from the chest downwards to the navel exposed, a wrap for the breasts, and a pair of shorts. It is composed of small pieces imitating black boxes sewn together into a garment “symbolising the constitution of Uganda.” It is reinforced with chains fastened at selected points with padlocks (Fig. 12) running from the shoulders to the legs. It could be argued that he borrowed ideas from hip-hop culture. However, he had an urgent political statement to make, that is: to show concern that the legislators had locked the general public out of the debate in which they amended the constitution “in their own favor.” Although ambiguously expressed in Ssebaale’s project, this selfishness and greed was widely debated since it became clear in the final text of the Constitution (Amendment) Bill, 2017 that members of parliament had extended their tenure from five to seven years. In addition, they received a lot of money from President Museveni in return for their “rented support” for the removal of Article 102(b).

Starting on April 9, 2018, the Constitutional Court of Uganda heard a petition (also called the Togikwatako case) in which lawyers represented individuals and groups who sought to challenge this extension, which Ssembatya thinks was “bad for the future of Uganda.”

During the hearing on the petition, the Deputy Attorney General of Uganda argued before the Court, and in front of the media, that it was necessary to amend the constitution “to lengthen the life of Parliament from five to seven years” and that “there was nothing wrong with that.” The petitioners opposed his submission. They argued that the Parliamentarians were being selfish. The amendment, which was supported by the majority of legislators, was an affront to the rule of law and constitutionalism in Uganda; it was unconstitutional. Delivering the leading judgement on July 26, 2018, the Deputy Chief Justice found that what the legislators had done “was most unfortunately self–serving. The reasons could not pass the requirement for reasonableness as a test for justifying the amendment of the Constitution” of Uganda. It was therefore unconstitutional for the tenth Parliament of Uganda to amend the constitution in order to extend its tenure from five to seven years. The Government appealed to the Supreme Court. In its judgment, delivered on January 15, 2019, the Supreme Court of Uganda upheld the decision of the Constitutional Court. All the artists whose work I have referred to in this segment were happy with the two court decisions.

Conclusion

Anchored on the theme “beyond fashion,” the Fashion Parade 2017 gave art students at MTSIFA an opportunity to experiment with fabric and color, engage with political activism, and express dissent. This use of visual expression for political action was not new in itself; it was rooted in the history of contemporary Ugandan art, which goes back to the teachings of Margaret Trowell, and its connection to debates on Uganda’s politics. However, in this case the students linked their projects to the volatile political terrain outside the art school and what is generally accepted as fashion as apparel in Uganda. As a result, the Fashion Parade 2017 was distinct from its predecessors in the sense that the students consciously used visual expression as an alternative to direct confrontation with the security apparatus of the state. It is interesting to examine their projects in the context of the violence expressed in political songs. It is also productive to examine their projects in the context of the repressive laws and the decisions of Courts in Uganda (Kenya and Malawi) which addressed the violent contexts which the students were aware of and to which they responded. We begin to see how some students at MTSIFA evolved a kind of creative deliberation that avoided violence. As such, though linked to the political campaign codenamed Togikwatako, the Fashion Parade 2017 at MTSIFA shed new light on the ways in which university students reacted to a harsh political environment characterized by abuse of human rights. They used drawings, apparel and the catwalk, and written and verbal statements as political devices, while expanding the meaning and shape of visual culture and the history of contemporary art in Uganda.

I argue that as a voice against repression, and in the defense of fundamental rights and freedoms, the Fashion Parade 2017 gave students an opportunity to push back against dictatorship and widen the deliberative space, which has otherwise continued to shrink in Uganda. I concede that the historical moment framing this parade was uniquely Ugandan. However, as a form of political activism and dissent, it cannot be severed from the other forms of activism in which popular culture has been mobilized on the continent (and the world over), to contest repressive governments and expand deliberative, public space. It adds to the lessons and models available to many who continue to face brutal police states and who are seeking alternative ways to creatively launch silent revolutions through which to speak back to authoritarianism, without necessarily resorting to violent confrontation.

Angelo Kakande is a Senior Research Associate, Department of Fine Art, Rhodes University; he is an Associate Professor at Makerere University. He is an artist, art historian and a lawyer. These broad areas (and their epistemologies) have nurtured his interdisciplinary research on the socio-political contexts in which art, art history, and the law intersect.

Notes

[1] Funeral Dress, Political Party Bullshit (New York: Punkcore Records, 2000). Retrieved from https://www.funeraldress.com/ and lyrics accessed at https://genius.com/Funeral-dress-party-political-bullshit-lyrics

[2] Phares Mutibwa, Uganda Since Independence: A Story of Unfulfilled Hopes (Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 1992); Samwiri Karugire, Roots of Instability in Uganda (Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 2003); Mugaju, J., & Oloka-Onyango, J. (Eds.). (2005). No-pary Democracy in Uganda: Myths and Realities. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

[3] Also available online at: https://www.parliament.go.ug/documents/hansards

[4] Margaret Trowell, “Makerere Art Department Exhibition,” Uganda Herald, July 10, 1946

[5] Sunanda Sanyal, Imaging Art, Making History: Two Generations of Makerere Artists, (Ph.D. Thesis, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, 2000); Angelo Kakande, “Contemporary Art in Uganda: A nexus between Art and Politics,” (Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 2008).

[6] Karugire, S. (2003). Roots of Instability in Uganda. Kampala: Fountain Publishers..

[7] Muwonge graduated from MTSIFA during the mid-eighties. He currently teaches there.

[8] The sculpture was exhibited at the Nommo Gallery located at Nakasero Hill, behind one of the official residences of the President of Uganda. Also seen in the photo, behind the sculpture, are the offices of Elly Tumwine, a four-star General in the Uganda Peoples Defence Forces. Tumwine graduated from MTSIFA in the late seventies to join the NRM/NRA; he produced paintings in which he celebrated the contribution of the NRM/NRA to the development of Uganda.

[9] For example, in 1996 Uganda held its first “no party” presidential election in which Museveni had so much local support that he garnered 75.5% of the votes. On the international scene, Museveni received endorsement from President Bill Clinton of the United States of America who visited Uganda in March 1998. Clinton popularized the narrative that President Museveni was among the “new generation of African leaders” who were the vanguards of economic and political reforms on the continent.

[10] Aili Tripp, Museveni’s Uganda: Paradoxes of Power in a Hybrid Regime, (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2010).

[11] Created by Article 82(A) of the Constitution of Uganda, the Leader of the Opposition (LoP) comes from the opposition party that has most representatives in the sitting parliament. Accordingly, section 6(b) of the Parliament Administration (Amendment) Act (2006) provides that the LoP “shall be elected by the party in opposition to the Government having the greatest numerical strength in Parliament.” Ocan is a Member of Parliament representing Gulu Municipality. She belongs to the Forum for Democratic Change (the FDC) which is the largest opposition party in the tenth Parliament, elected in 2016.

[12] According to section 6(d) of the Parliament Administration (Amendment) Act (2006) the LoP “shall be accorded the status of a Cabinet Minister.”

[13] Under section 6(e) of the Parliament Administration (Amendment) Act the LoP “shall study all policy statements of government with his or her shadow ministers and attend committee deliberations on policy issues and give their party’s views and opinions and propose possible alternatives.”

[14] Betty Aol Ocan, “Restricting civil space for opposition is limiting alternative leadership for Ugandans” Available at: https://eagle.co.ug/2019/01/07/restricting-civil-space-for-opposition-is-limiting-alternative-leadership-for-ugandans.html (accessed August 15, 2020)

[15] Jo Coghlan, “Dissent Dressing: The Colour and Fabric of Political Rage.” M/C Journal 22, no. 1 (2019)

[16] James Procter, Stuart Hall (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), p. 11

[17] Museveni’s statement was circulated widely by the print and electronic media. See, for example, “Bobi Wine is an enemy of progress in Uganda, says Museveni” in the Daily Monitor Online, October 18, 2018. Available at: https://www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Bobi-Wine-an-enemy-progress-Uganda-says-Museveni/688334-5316766-e4gfb7/index.html (accessed August 16, 2020)

[18] Miscellaneous Cause No. 313 of 2017.

[19] See: Peter Levine, “Habermas with a Whiff of Tear Gas: Nonviolent Campaigns and Deliberation in an Era of Authoritarianism” In Journal of Public Deliberation, vol. 14, no. 2. (2018). Available at: Available at: https://delibdemjournal.org/articles/abstract/10.16997/jdd.306/ (accessed 16 August 2020

[20] Angelo Kakande, Echoing Silences: Graffiti and the Defence of Constitutionalism in Uganda (forthcoming, 2021)

[21] John Gastil, “Why I Study Public Deliberation,” Journal of Public Deliberation vol. 10, no. 1 (2014), p.3.

[22] Rebeka Uziel curated the show presenting ceramics, sculpture, jewellery, fashion design, painting and multi-media. Some lecturers explored new media and upset the conventional definitions of art making. However, the majority relied on mundane themes derived from normative cultural traditions and the country’s flora and fauna.

[23] Brenda Namazzi produced drawings and text to give context to her project. They are the source of this and the other material cited hereunder.

[24] Kakande, Contemporary Art in Uganda, p. 227.

[25] For example: Article 17 of the Constitution of Uganda provides that it “is the duty of every citizen of Uganda . . . to respect the . . . flag”; Section 4 of the National Flag and Armorial Insignia Act provides that: “(1) No person shall, without the authority of the Minister, use or permit to be used in connection with any business, trade, calling or profession the national flag or the armorial ensigns, or a flag or device so nearly resembling them as to be calculated to deceive, in a manner calculated to lead to the belief that he or she is duly authorised to use the national flag or armorial ensigns, as the case may be, in that connection. (2) Any person who contravenes this section commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a fine not exceeding one thousand shillings or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding six months or to both such fine and imprisonment.”

[26] It is a painting done with a limited color palette depicting an open landscape littered with a lot of debris. It is here that a young boy sips a drink using a straw while stepping on a Uganda flag randomly spread next to a leaking water tap symbolizing wastage.

[27] Phares Mutibwa (1992) makes a similar point in his book. see his: Uganda since Independence: A Story of Unfulfilled Hopes. Kampala: Fountain Publishers..

[28] Ssebatya exhibited a mood board for his work, on which he placed images and text giving context to his work. It was a good source for a lot of background information including this one cited here.