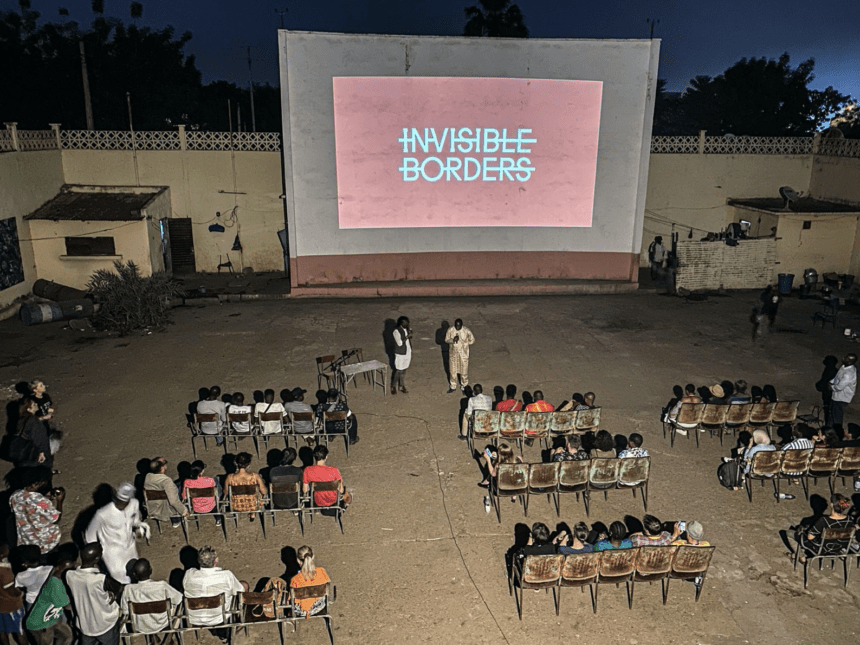

A Volatile Negotiation Between the Past and Present: Invisible Borders Trans-African Project

Emeka Okereke

The first decade of the 21st century has seen the ushering in of new and progressive creative impulses in the African continent. In Nigeria, it was perhaps heralded by the beginning, in 1999, of the longest period of democracy since the country’s independence. In South Africa, one could easily say without going entirely off the rails that Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1994 was a significant symbolic moment in this regard. These are only two of many indicators. I began my artistic practice precisely in 2001—only a few years clear of the era when such vocal activists as Fela Kuti were brutalized, with apparent impunity, by the government for speaking out against injustice. Nevertheless, it was at the same time that the disciplines of music, film and the visual arts (including photography) as we know them today began to flourish truly. In other words, the viability of self/creative expression increased exponentially with the advent of democracy.

Thus, there seems to be an inkling that we stand at a great turning point in the destiny of Africa and her peoples; one that would see many of today’s generation be forerunners of a more progressive century. That being said, we must be cautious of getting ahead of ourselves: a more urgent position than reiterating the “Africa is the future” mantra is to be fully immersed in the present. To proactively participate in the processes of meaning-making that, in turn, underscore the complexities and precariousness of dealing with the vestiges of colonialism which continues to reveal itself in uneven distribution of wealth, misplaced priorities in governmental policies, corruption, and spatial gentrification, to name a few.

The Invisible Borders Trans-African Project is one of the many projects which attempts to align with this viewpoint. I founded the project in 2009, and its aim has been “to work with individuals and organizations in the patching of the numerous gaps and misconceptions posed by frontiers within the 54 countries of the continent” [1]. Through photography, writing, film, performance and site-specific interventions, African artists and thinkers have come together to reflect on the socio-politics of movement. The flagship project has been the Trans-African Road Trip, which as of January 2020, is in its 9th edition. The artistic road trip has seen African artists travel across borders of more than 20 countries in Africa, but also beyond— through Europe. The pioneer members and participants include Ray Daniels Okeugo (1980 -2013), Uche Okpa Iroha, Amaize Ojeikere, Uche James Iroha, Nike Adesuyi Ojeikere (1968 -2016), Lucy Azubuike, Charles Okereke, Chriss Aghana Nwobu and Unoma Giese. Later and recent members include Emmanuel Iduma, Jumoke Sanwo, Tom Saater, Ala Kheir, Nana Oforiatta Ayim, Kenechukwu Nwatu, Kechi Nomu, Delphine Wil, Kosisochukwu Ugwuede, Innocent Ekejiuba.

This article will expand on the complementary association between process and outcome in the generation of thoughts and knowledge within the Invisible Borders Trans-African Project; a performative intervention which invites African artists to employ their body, and presence, as objects of useful agitation in the negotiation, and by extension, remapping of artificially imposed cartographies. For the past ten years, the artists have, through remarkable encounters and experiences, witnessed “the ground shifting under our feet”—a process taking place all over the continent on various scales and contexts.

The article will discuss two phrases that profoundly inform the concept of the road trip: “a journey through volatile negotiations between the past and present,” and “I am where I think.” The former speaks to the trajectory and the kinopolitics (socio-politics of movement) within countries and borders that constitute the route. The latter, on the other hand, is a decolonial position which firmly grounds the intentions of the project on “epistemic affirmations [knowledge(s)] that have been disavowed” as Walter D. Mignolo puts it. [2]

Many of the views expressed in this piece draw from my experience of the project mentioned above having—as the founder, artistic director and participating artist—coordinated and participated in all but one of the nine editions of the Trans-African Road Trip between 2009 and 2020.

On Borders

As we looked for ways to traverse from Nigeria into Cameroun through the Benue River, I would think of Homi Bhabha’s “interstitial space,” of Chinua Achebe’s “middle ground,” of Gayatri Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” and of Glissant’s “here and elsewhere”.

I would think of roots and routes. Their correlation and dissimilitude. Roots, as in origin—an identity so to speak. Routes: myriad threads of paths intersecting, intertwining. I would think of everything that could fit or unfit in between.

I would think of the root that does not kill other roots around it as it searches for its food and water, or its depths—its foundation. I would think of roots that enter into relation with other roots—like rhizomes. They hold hands and twist into each other. They are not dots in a line, but circles forever intersecting—giving way to ever new centres, new peripheries that in turn become centres.

I would think of words I have used in the past, and which I continuously use because they hold, for me, something refreshing in their continuity. Words like: fluidity. Ephemeral. Air. Sky.

I would think of borders and of how—elusive to many—they are outward manifestations of doctrines of divisions. But their elusiveness is also their mirage-like nature. Come close enough; they disappear only to reappear in the furthermost horizons—always on the road, on the path of the beholder.

There is really nothing there. But how would you know if you never go?

– Sound of Water Waves: Of Crossings and Landings, Day 29, Yaounde. Lagos – Kigali Trans-African Road Trip 2018.

In Ursula Biemann’s film Performing the Border, the protagonist is heard saying that there will be no border if there are no crossings. The very notion of crossing carries within it the constituent character of a border. We can equally call this “the necessity of traversal” inherent in that which is the heartbeat of nature: movement.

A prominent feature that complicates the above deduction is that borders are also highlights of lines of associations that play the constructive role of framing entities according to their homogeneity such that a world without borders is a world of utopia.

In as much as soliciting for a borderless world is equivalent to calling for an implosion of our social formation as we know it, should we not seek to converse the permeability of these borders especially in the backdrop of increasingly multifarious social formations obliged to contend with each other? Should we not begin the arduous task of learning to live with one another, not merely in the sense of tolerating each other, but in respecting the processes by which our differences manifest and learning also to see “different” as an inherent qualifier of any exchange?

Borders are porous. Where they are the opposite, they are ossified more likely by the tendency to eliminate than to elucidate. Borderlines are immediately made rigid by the need to devise a formula to be applied systematically in order to arrive at a specific form of classification. They are mass-produced and commodified all in the guise of rhetorics such as progress, development, civilization, industrialization, and not least, globalization—always in relation to an “other.” At first, this mimics expansion, but on the long run it is a congealed version of a much more effervescent force which has lost its quality of fluidity—that which can facilitate intersection between unlike entities.

Borders are vacuums, whose tangibility is reinforced by the outward posturing, power mechanisms and kinopolitics between entities. The impact of these vacuums depends on the attitude of the entities towards each other: They can either chose to “feed off” this vacuum, thus widening the void, or decide to scale the vacuum, intertwining with each other; making the void a stage where the nuances or misconceptions of their relationship are played out.

Borders are retroactive—preconceived notions. Of a place, of people, of self, sustained by one’s personal history and idiosyncrasies cocooned in a broader societal context. It could be weaponized as self-defense under the guise of “personal identity”—that often conjured a sense of safety—towards the collective.

Borders are related to the gaze—how one has been taught to see and to be seen as a way of projecting unto the other the fear of the stranger one might become to oneself should one surrender to what the road in one’s life offers.

Borders are walls of mirrors replicating, to the point of distortion and absurdity, the image of self, such that memory and language, and thus poetry, are entrapped in the vortex of predictive repetition. This replication has the effect of moving outward from a minute point of origin—say, between persons sitting facing each other, in a commuting vehicle; wondering what to make of their perceived difference—to settle at the peripheries, caking into strict necropolitical outlines by which the margins of a nation-state are delineated.

Transcending borders begins with the will to journey along imposed cartographies beyond where their lines falter; to make way for viscerally lived experiences through which we reimagine their contours. When in 2018, we opted to take a road trip from Lagos, Nigeria to Maputo, Mozambique; we were not ready, despite our preparedness, for how much the cartography would treat us like antibodies. Nevertheless, the more difficulties and resistance to forward movement we encountered (for example, getting stuck at the Nigeria-Cameroun border due to the armed conflict unfairly called The Anglophone Crisis), the more we were consoled by the humanness of our encounters with the people whose lives and activities animate those borders. Their stories hardly make it into the pages of mainstream media except for when they are eventful enough to make for “good news.” We take it upon ourselves to preserve some of these stories in our blog, almost daily, as we journey. [3]

“Trans” As a Prefix of Relation

As I write, I am in a van. It is February 2020. We are on our 9th edition of the Invisible Borders artistic road trip project which, for the past decade, has seen mainly photographers, writers and filmmakers from the African continent traverse borders while reflecting on their encounters; in the process, creating works that serve as precipitates of border experiences.

This time, we are in Bangladesh in South-East Asia. For the first time in the project, we decided to embark on a road trip project in collaboration with another media agency outside the African continent. The Drik Media agency, together with Pathshala South-Asia Media Institut and Chobi Mela International Festival of Photography, all founded by Shahidul Alam in 1989, 1998 and 1999 respectively, represent arguably the most potent platforms through which the power of photography is exploited, articulated and placed at the service of the sociopolitical realities of Bangladesh. Pathshala Media Institut has trained hundreds of Bangladeshi photographers and journalists since its inception. The Chobi Mela International Festival of Photography has become an essential platform for the dissemination of photography. Drik Picture Library invests in the documentation and archiving of Bangladesh’s photographic history.

The collaboration between Drik/Pathshala/Chobi Mela group in Bangladesh emanated from the need to elongate the spectrum and operative context of Trans-Africanism upon which the Invisible Borders project was established. It seems apt, at this point, to attempt a delineation of Trans-Africanism, particularly in relation to Pan-Africanism. If Pan-Africanism offers a container for uniting peoples of African origin under a common race, history and destiny, Trans-Africanism, while building on the foundation laid by Pan-Africanism, seeks to become tentacular in its goal of affirming the great extent to which Africanness permeates or enters into relation with the world. If Pan-Africanism presupposes a foundational grounding in one’s Africanness, Trans-Africanism involves putting one’s consciousness into action in generating unique thoughts, experiences and stories through remarkable encounters engendered by perpetual movement.

The Trans-Bangladeshi Road Trip signals a turning point, a milestone that, in succession, coincides with the beginning of a new decade in the project’s lifespan. Since 2009, much of the preoccupation of the Invisible Borders Trans-African Project is rooted in attempts to articulate a postcolonial/decolonial premise—specific, but not limited, to African realities—with regards to movement, fluidity, cross-border exchanges and sense of agency in an increasingly subjectivist, post-nationalist, yet neocolonialist world. Thus, in a 2012 essay, I analyzed the nature of the term “African” when the prefix “Trans” is attached to it as a qualifier:

The prefix Trans- by definition connotes “going beyond”, “transcending,” and in some cases implies a thorough change. It suggests dynamism and vigour—that from which something unpredictable emanates. It equally implies crossing back and forth, like in an [osmotic] exchange, and wherever there is an exchange, a boundary is traversed into unfamiliar spheres where another dimension takes on existence.

Although this term has been used mostly in relation to economic factors as it pertains to particular geographic structures such as in the case of the Trans-African Highways—roads constructed across the continent by the African Union in collaboration with The Africa Development Bank aimed at promoting trade in the view that it will consequently alleviate poverty, it could equally apply as a metaphor for the method of artistic exchange, or any other exchange for that matter, in Africa today.

The Trans-African artist is the artist whose sensibility transcends or goes beyond the pre-saved definitions of what constitutes art from Africa. They draw inspiration from exchanges between peoples of diverse [ethnicities] and countries within the continent without having to contest, compare, or seek validation for these sensibilities. They do not seek a definition of Africa in their African-ness because Africa is what they make of it and not the other way around. Trans-Africanism is the ability to transform African-ness into fluid forms that need not be defined. It is not an outside covering, but an inside mechanism of networks and exchanges. [4]

In Bangladesh, the proposed project—a ten-day journey stretching over 2000 kilometers across Bangladesh while making stops at five towns where the country borders India—was called The Trans-Bangladeshi Road Trip (after our 2016-17 Trans-Nigerian Road Trip). There were four artists of Invisible Borders travelling, living and conversing together with five artists from the Drik/Pathshala/Chobi Mela group. Not only did the project offer a unique frame for the exploration of border configurations and realities, but it also signaled a culmination point in the decade-long reflection on (invisible) borders as “the distance sandwiched between preconceived notions and freshly acquired perceptions” as related to a place or people. It provided the needful occasion to examine the project beyond the prosaic form of borders as a geopolitical entity, and to articulate the role of the body—imbued with memory, thus language—as an object of useful agitation in the negotiation of borders. Thus we spent a reasonable amount of time reflecting on what it means, as thinking bodies, to indulge in the physical, performative act of stretching our bodies 2000 kilometers across contested cartographical points. To what extent does our body and presence—entangled in precariousness, both of self and that which the road offers—rupture, contaminate, reconfigure and remap that which we seek to measure? What do we make of the tensions between the subjective and the collective underpinning every communal endeavor? The works produced by the artists are residues of these questions.

Aesthetics, Process, (Re)presentation

I am of the firm opinion that art practices and processes, especially in the African context, should aim to reach out to ordinary people within public spaces. As we travel, traversing landscapes and territories sliced by milestones and town signs, I am compelled to reflect on what public space means. It is not so much the physical space as it is the social space of the people who occupy a given physical space. If we dwell a little while on the immateriality of reality, it suffices to say that physical space itself is a derivative of the intricate networks of events, perception, and personalities embodied by the people within the space—this is the real public space. Every work that intends to exist or work with public space must put into consideration or dialogue the everyday reality of which physical space is a function. Physical space is a function of social space, and social space is a product of the immaterial radiations of those who occupy it.

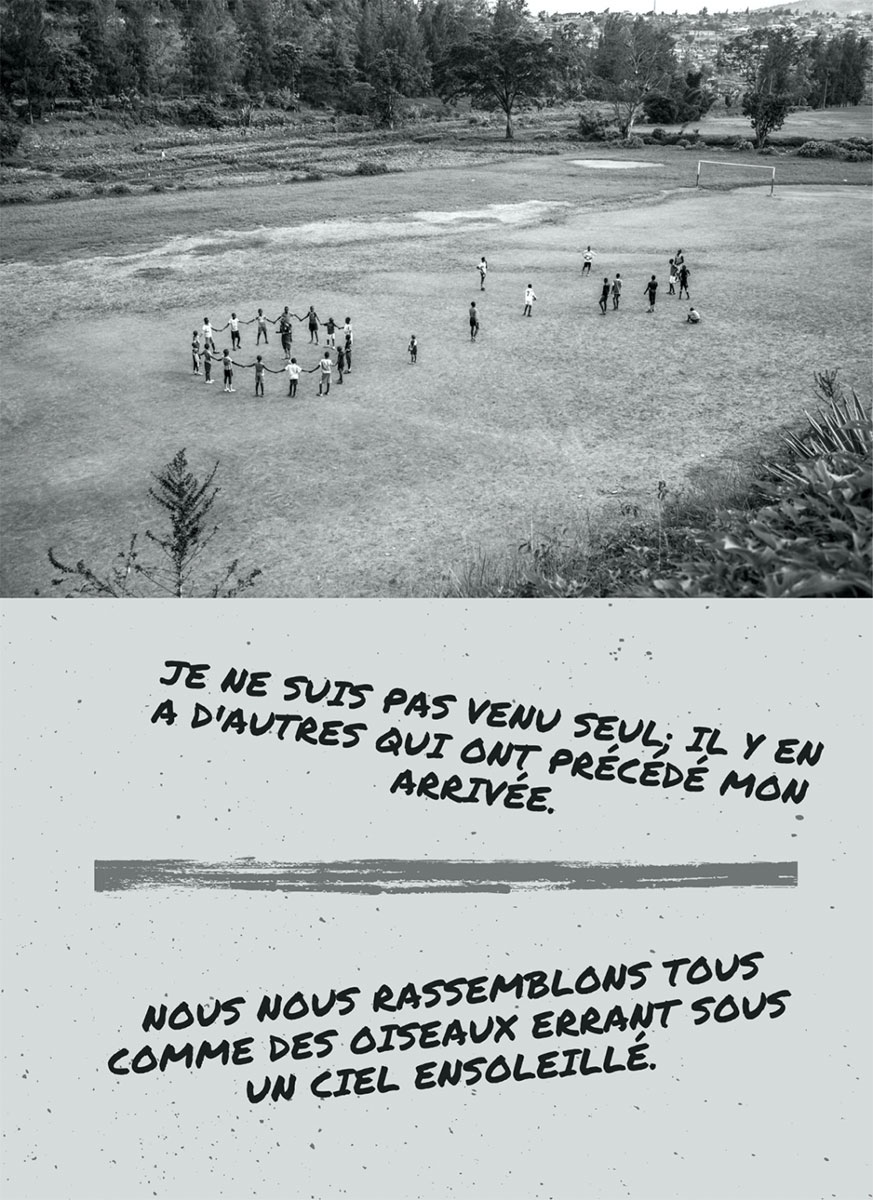

African public space, as we know it, is foremost a communal space. It expands outwards, as it concurrently fragments into pockets of different happenings and configurations, to become a space of proactivity charged with living energy emanated by people who by every gesture of movement are negotiating, breaking with body and presence, molding and remapping an imposed spatial design and cartography. Although today, much of this is being pushed to the fringes by privatization, gentrification, and sometimes militarized operations. This reality is more evident in burgeoning capital cities such as Lagos, Yaounde, Kampala, Bamako and Dhaka than in the rural and provincial regions of the country. Nevertheless, go into market spaces or parts of the city called “quartier Populaire” in the francophone city of Yaounde, the assertions expounded above are more or less the case. We spent ten days of the 2018 Trans-African Road Trip in Yaounde, all the while staying and working on “rue de la Joi” (the street of joy). It bubbled with enough activities and interactions, at all hours, to live up to its name; indifferent to the armored trucks full of gendarmeries positioned at the Kennedy Square, at the city center.

Achille Mbembe once remarked that what he finds most intriguing about African public space is that wherever one goes, people are engrossed in the constant act of repairing, recycling, and mending. I agree with this assertion. The act of perpetually “repairing” mirrors its biblical equivalent of “turning stone into bread.” Sparks of miracles shoot out from all corners, interiors and sidewalks like streaks of lightning preceding a thunderstorm. All of this is reflected in the relationship between space, objects and people such that every object, taking into consideration its posture, position and relation in space, is an articulation of a people’s interaction and human trajectory. While there is a great deal of effort channeled towards organizing, compartmentalizing, segmenting and ordering space in many of the Euro-American towns and cities, with Africa, spatial design in a postcolonial context is a function of a people’s will to transcend the limitations imposed on them by a neo-colonialist, imperialist, capitalist, patriarchal reality.

Thus, in the Invisible Borders project, we insist on accounting for these tendencies, through our photographs, writings and film, not as a life of aimless, endless struggle, but as a process within the negotiation and reclamation of a people’s agency. It is the content, however, disassembled and multifaceted, of any would-be African unity. Sometimes, this has necessitated the need to speak to the grim side of things—the seeming futility of an uphill battle by citizens weighed down by the nature of their country’s political conundrum:

In Yaounde, everything seems like business as usual. Some people have said this is stability. However, I, for one, see definite signs of docility—docility which has taken the form of fear of the unknown. When people stand in long queues waiting for transportation back home after the day’s work, one sees on their tired faces a kind of unredeemable resignation. But like the taxi driver who drove us from Bernake to Garoua as we entered Cameroun from Nigeria alluded to, Paul Biya has been in power for so long that he has become the cap on the limit or the horizon, if you may, of people’s hopes and aspirations. He is a father figure. I would return to this father-figure notion during a conversation with some of my colleagues on the road. You do not, especially in Africa, reject a father on account that he is a bad father. His place and reverence will continue, more so, if he has not yet earned the ire of the Western world to attract outrageously negative publicity for which the people would consider even a semblance of revolt. [5]

As we evolve in the discourse surrounding borders, it becomes imperative not to undermine the performative, but also non-reactionary, nature of this intervention as an ideological/philosophical foothold: to make it central to its aesthetics of representation. Our aim, therefore, is to continually look for ways to present this project as an intervention within the everyday reality of the regular inhabitants of any given geography, taking into account the element of spontaneity and improvisation, which are the core ingredients of uncurated interactions.

If today someone asked me what exactly is contemporary Africa, I would first speak of radiations, a kind of energy which flows through the continent like a continuous line. This energy, this radiation, is what numerous people coin words to define. It has been there from the onset, and no matter how time changes, it surfaces in myriad forms; it is ever constant and re-inventive; it permeates everything and everyone whose feet are rooted in the continent’s soil and thus has long since become our nature. This radiation gives rise to the shared reality of the people of the continent. In the same vein, it is nourished and fine-tuned by the struggle to circumvent unfavorable situations, which loom above the destiny of the people. It is what gives rise to the “arbitrary” indefinable, and often paradoxical, nature of existence in the continent. This energy is the unequivocal tendency towards spontaneity, the sheer extent of improvisation—that which flaws any form of pre-defined statistics. It is said that in Africa the weatherman is always wrong. Why? Because naturally, people live shoulder to shoulder with the moment, and between two moments, there are one billion ways of being.

Living in this reality is like being in a space where everything is non-linear, shapeless, yet this is the shape because it works. It reevaluates the defined and invigorates the stagnated. It grounds interactions in the present such that it seems far-fetched to base one’s reason for action on the awareness of the past or the assumptions of the future. This, however, does not mean that people do not make plans, but this planning is never incapacitated by pre-defined projections. Every moment is a stand-alone even though one leads to the other. Therefore, to be “African” is to blur the lines between the possible and impossible, rendering the real state of “being” indefinable. It is to become conversant with, to ascribe value to, the complexities and maneuverings of fluidity.

This radiation, this energy permeates everything but manifests prominently through the everyday space of African peoples—the public space, where all the drama of living and coexisting is symbolized. Our work over the years followed this trajectory and hinged on depicting the exchange, the interaction of people and things within public space; looking at what one might dismiss as banal. By the act of “putting a frame to them,” we extract them from the ordinary. We are consistently conscious of the fact that no click is a waste as far as posterity is concerned.

Our approach to imagery, therefore, goes beyond making “beautiful photographs” or the need to show astuteness in photographic skills or capturing “decisive moments.” For us, the real story—often left out in the quest for blatant headlines—is embedded in the indecisive moments. We are more interested in how the approach to imagery mirrors the reality that we are immersed in, rather than how images define or ossify this reality.

In thinking of imagery within the Invisible Borders Trans-African Project, and subsequently its presentation, we account for the in-betweenness of border realities: many people and places exist, live and survive in bracketed spaces. The migrant stuck, for many years, in an enclave in Tangier, waiting for her life to resume signaled by the crossing into Spain is only but one of many figures whose lives are in parentheses. We account for the duality: “where one thing stands, another stands beside it,” as inferred by the Igbo cosmology. We account for moments of opacity when, for instance, we say “dark corners are spaces of intimacy; of freedom.” Freedom to create, freedom to fail, freedom to immerse oneself in process rather than harassed by the pressure of pre-defined outcomes—a methodology standardized by the mainstream media, NGOs and aid industries whereby fixed expectations precedes, and as such constricts, the effervescence of process. For us, the journey is more important than the destination.

In a world obsessed with the thingness of things—where achievements are weighed based on the weightiness and presence of matter—we embrace ephemerality as a response to the transient nature of the road and border spaces.

In past years, what has become challenging is not only the struggle to permeate the implications of borders but also (1) what ways to use the different media at our disposal to question and invigorate discussions about limitations in Trans-African exchange (2) how to present and interpret the project in such a way as to convey the authentic experiences of the journey as a performative endeavor for which the process is the outcome.

As we progressed from one edition to the other, so did our experience. We have come to the realization that borders could act as a double-edged sword, and therefore ought to be considered meticulously. For instance, the notion that borders are something tangible and eradicable is naïve. Borders happen when an individual or a group of people will upon themselves to transcend the norm. Thus the protagonists of this project are foremost the participants and the very first intention to go beyond the norm—the act of becoming a fiction in other people’s reality using themselves—their body and presence—in the negotiation and articulation of border logics. Such positioning gave form to performative images depicting participants projecting their bodies—while alluding to the interplay between the subjective and the collective in their spatial formation—unto a questionable history. I speak of the image titled “Participants at Lugard’s Rest House. Lokoja, Nigeria” made on the occasion of the Trans-Nigerian Road Trip in 2016. This image goes as far as interrogating and makes dry humor of the amalgamation and naming of Nigeria of which the then British Colonial Governor, Frederick Lugard, together with his wife Flora Shaw, were progenitors. It is said that Flora Shaw named Nigeria presumably during a get-away-weekend at the Rest House-now-turned-monument at the top of Mount Patti, overlooking the Niger River. Nigeria was coined from a combination of two words: Niger and Area.

On the road, things happen at random and at a pace that could not be likened to a routine—we are always on roller-coaster mode. We make plans and we counter-plan so much that haphazardness becomes our orderliness. It is never realistic to see the trip as one definite thing. It encompasses everything—failure compliments success, and vice versa. It is where “wrong” is not easily written off as the opposite of “right”, but could be seen as its precursor or its consequence. When we travel on the road trip, we see flashes of images; not one photograph or two. It is a disservice to the experience to speak of a selection of images in this context. How can we “freeze” a moment when we are swamped with infinite moments?

Sometimes the image made does not justify the experience lived, and this amounts to a kind of frustration. Add to that the shortcoming of the camera, the lens, view and limitations of materiality. The window screen shielding you from the expanse out there, the van constantly moving, bumping—your position displacing at 100 miles per hour (so are your thoughts). One loses all of this to the click of the camera. Therefore, the indecisive-moment images tell the story much more than the decisive. The exact nature of the African Space is that swarming with unquantifiable moments carrying in each one of them an integral part of the people’s existence and by that, their history. Therefore, every click of the camera, every stroke of the writer’s pen, the record button of the filmmaker’s camera, is history in the making.

In photographing, writing and filming the “banal,” we focus on those tiny moments, which give the “headlines” their backbones. Our concept is surmised as follows: to highlight the everyday interaction between people and the space they occupy; with time and consistency, we would have created an archive of how people shared in their various modes of coexistence—the intimacy, the beauty, the harmony as well as the many ways these are contradicted and complicated.

We are not interested in the photographic nature of imagery but its performative nature. I do not use the word “performative” here to mean the antithesis of “real” or “unperformed” but rather as a frame that allows for the kind of feedback loop characteristic of dialogue—that which emphasizes process as an essential precursor to outcome (we find iterations of this feedback loop in the call-and-response nature of African folk tales and such musical genres as Afrobeat). There will be no decisive moment without the myriad indecisive moments sandwiched in between. It is also in line with this logic that we proclaim: there is no “African unity,” without prioritizing our understanding of the complex, arduous process in between. What then, if otherwise, is the content of this African unity often spoken about?

As the project has evolved to become a trans-media project, intertwining, almost in equal parts, photography, writing and film, our exhibition has sought to centralize these thoughts in such a manner as to retain the ephemeral, transient nature of the project while referencing the complementary association between process and outcome. The near-best form of presenting the project so far—besides tentacular activities such as workshops, presentations, site-specific interventions and readings—has been an installation that depicts a performance of imagery, writings and film as a constellation of multimedia components. The exhibitions are not a showcase of outcomes as much as they are a furthering of the conversations begun on the road. Thus, the exhibition invites the audience to partake in the journey; to weave, through innate orientation, their imaginary of space, time and self. The exhibitions do not presuppose thematic narratives but aim to make the audience complicit in finding their subjective compass with which they remap the imposed cartography.

This was the inspiration for the project’s installation at the 2015 Venice Biennale, at the invitation of the late Okwui Enwezor. Titled “A Trans-African Worldspace,” the Invisible Borders presentation consisted of video projections, images and texts, set up as a constellation of impulses, experiences and deductions from materials generated from five editions of journeys across myriad borders. Spread across two rooms, open at both ends (as a way of enabling a cross-navigation of the space bearing in mind the visitor’s unique sense of orientation) the installation was designed to immerse the visitors in the processes of the road trip through a collage of images, audio-visual documentation and cartographic depictions. The video projected on the wall of the Arsenale had a specific aim: just like the image of the participants at Lugard’s Rest House discussed above, the video served to superimpose the project’s narrative onto the walls of the Arsenale—a building which, over many centuries, facilitated much of Venetian naval power and maritime trade, roping in Indians, Arabs and Africans in the movement of goods and slaves in the Mediterranean.

At the 12th edition of the Bamako Photography Encounters, the focus was mainly on public space interventions. Seventy-two posters generated out of images and writings from the road trip were exhibited in six out of eight districts of Bamako. They were strategically placed to ensure unplanned/unscheduled engagement with indigenes of Bamako from all walks of life. The texts were translated into French.

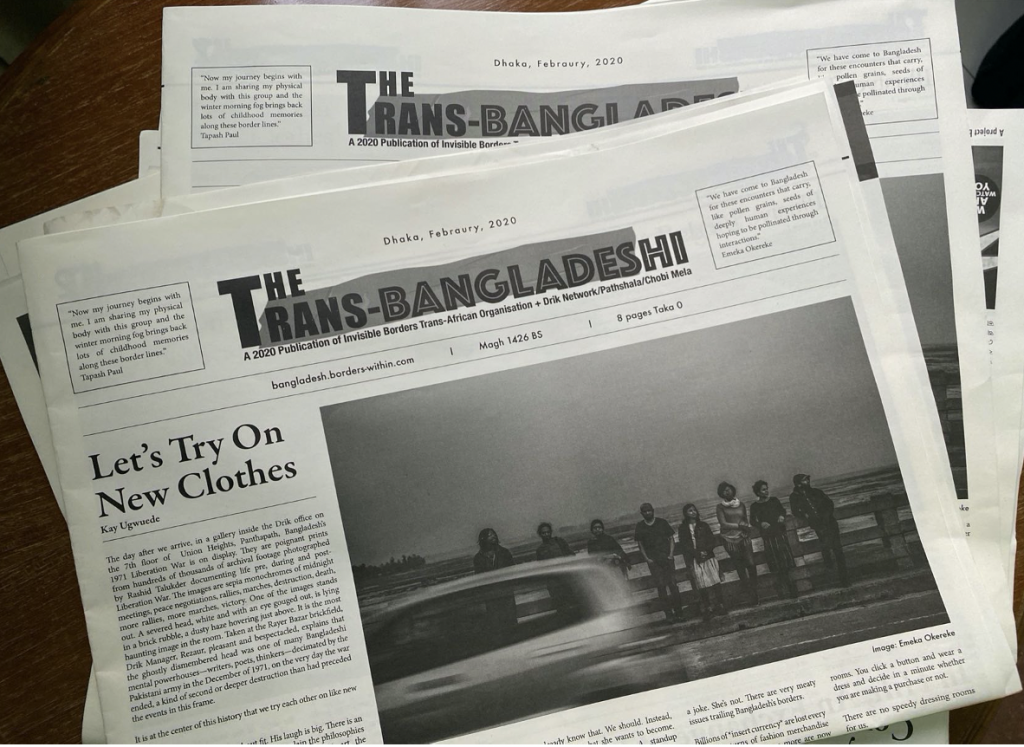

At the Dhaka Art Summit in 2020, the Trans-Bangladeshi Road Trip was presented in the form of a newspaper journal consisting of works from all the participants—photographers, writers and filmmakers—of the project. In the course of our time in Bangladesh, we observed that newspaper prints remain the primary means of dissemination of information. Thus, 5000 copies of the newspaper journals were printed and installed in the Art Summit. The visitors were also allowed to take copies of the newspapers with them. We also shared many copies around strategic areas of Dhaka. The newspaper was produced in English and Bangla.

It is imperative to state that we aim to go further than the act of image-making; to seek ways to put imagery to use as a performative tool, to use the Invisible Borders Trans-African project as a platform for the articulation of the psychology, philosophy and critic of post-slavery, neo-emancipatory, Africanness in its varied possibilities. We are continually asking the never-ending question: How can we use photography in such a way as it becomes a tangible act of social intervention rather than art for art’s sake? How can seeing with the eyes carry the entire body along? How can we extend the thoughts and experiences articulated through our photographs beyond the esoteric confines of the literate and the art world? Conversely, how can we inject into art /the art milieu the same enthusiasm, emotions, curiosity and humanity evident in mundane life?

The Collective in the Subjective

The Invisible Borders Trans-African project is not a collective as much as it is a collective way of being and thinking. It is a project that fully recognizes that the journey from point A (the individuals who come to the project with their limitations, assumptions, preconceived notions as well as strengths—a function of a defined “self”—the subjective) to point B (freshly acquired perception, clarity, intimate knowledge; the collective) is full of tumultuous tensions, precariousness, and thistles of inconsistencies. We do not shy away from this reality. It is not a safe space where this means comfort, self-preservation, and exclusion from the complexities and inexactitudes of the world encapsulating it. If anything, it is like Chinua Achebe’s middle ground: “the home of doubt and indecision, of suspension of disbelief, of make-believe, of playfulness, of the unpredictable, of irony.” [6]

The project embraces these tumultuous tendencies; more often than not, this is the nature of the road and the ground shifting under our feet—to reset and remap imposed cartographies. More than bad roads, more than stringent border posts, what has been most threatening in the project’s course, is subjectivity’s tendency to curl up into itself—and by so doing weaponize itself against the collective—at the slightest sensing of losing its protective shell; what Toni Morrison refers to as the fear of losing “one’s own valued and enshrined difference”.[7] When the subjective operates this way, it is only a thin line shy of being xenophobic towards the collective. On some occasions, with some participants of past Trans-African Road Trip project, we have had to deal with the ugly consequences of well-meaning intentions that deteriorated right at the crucial point where the collective was to be birthed.

It was in 2010, the 2nd edition of the Invisible Borders Trans-African Road Trip, that we had our first experience of a participant quitting before the end of the project. Ever since, we have had to deal with the rupturing effects of disenchantment and disillusionment experienced by some participants. The 5th edition of the Trans-African Road Trip from Lagos to Sarajevo in 2014 was the longest and most arduous. By the time we got to Sarajevo only four participants out of the initial ten who began the journey in Lagos were still on board. The reasons for the participants leaving the project midway were as valid as they were subjective. Yet, it is worth noting that there simply was no way of completing a journey of such magnitude and mileage if the focus was not on the collective—something greater than the subjective. That was how impossible the four and a half month trip was, for some. Much like Edouard Glissant’s take on the space of relation, there is nothing passive in the collective. It feeds on our resolve—stretching it across long expanses of road. The further we come in togetherness the stronger the collective becomes.

Thus, if the subjective is to be purposeful, it must first find its place in the collective. There is no subjectivity for subjectivity’s sake. The subjective ought to be at the service of the collective. Put differently, the collective is a precipitate resulting from the sublimation of the subjective. When we allow ourselves to think of the collective, not as a flattening of subjectivity but a sublimation of it—for which duration, location, cultural contexts, personal histories across space and time are vital catalysts and solvents—we envision a more connected world held together by different degrees of tautness upon which our actions travel. The subjective will curb the extent to which—at the slightest awareness of its insecurities and fears of the impossible—it becomes a threat to the collective. Then, the collective will be directly proportional to how less we expect a direct or immediate gratification for every time we give of our self.

I am Where I Think: A Decolonial Option

When all is calm, you will hear the roars of the lake. Smell the aroma of [the] dancing wind.

And soon the birds will sing in unprecedented unison––melodious yet so purposeful. As if to declare a new day born.

A lot has been said of a city. Of its beauty or not.

Of its warmth even in chilly evenings

Of its mountains and volcanoes

Of pestilence and turmoil

A lot has been said of a city and its people––from above and abroad.

From miles away, safe from the disquietude of intimate knowledge.

Yet here, boots on the ground, walking on black earth, contours and textures of beauty are questioned––from within––flipped upside down, literally.

Colors spew from the crevices of erupted paths. Paved not long ago by hot rocks––today, a tapestry of a people’s resolve to make life matter.

Vigor of living relentlessly dousing the hopelessness peddled by the presence of barraging “humanitarian” agents and peacekeepers of United-dis-Uniting Nations.

I am where I think. A needful refrain,

A constant reminder that life moves as one move.

Like all the stories of distances from which Goma was born.

Now, I have stepped out to the balcony again,

Before me, Lake Kivu.

In all its calmness and straight-face, it is hard to tell the line where it joins the sky.

I remember tales told of the arrival of the Bantu and Neolithic peoples. And how they crumbled further into minuscule parts, here.

Things have never been the same.

Once in a while, a message comes from the peripheries. Carried on the faces, and held banners, and quiet, unobtrusive protest, of Hutu youths.

A message to their Nande brothers.

Those faces, as flat, as blue, as unreadable, as the surface of the lake.

The volatile negotiations continue––as if the lava boils.

Indeed the lava boils.

Let the blues of the lake not fool you.

Underneath, fishes scurry for cover––back and forth the border. Not caring in the world where Congo stops and Rwanda begins.

Not caring when last the surveyor checked the dividing lines between peoples.

– Even Stones Speak: Goma, A Recap, Day 42, Lagos-Kigali Trans-African Road Trip 2018

As a project firmly grounded in the notion of movement while aiming to traverse the power mechanisms/dynamics necessary for its flow, we realize that much of the work to be done lies not in what newer knowledge is produced or acquired, but how old knowledge is reimagined and re-historicized. In more precise terms, we are in the thick-middle of a volatile negotiation between the past and present. “I am where I think” points to the need to be cognizant of a multi-contextual world with as many centers as peripheries. Edouard Glissant’s “Poetics of Relation” (to be here and elsewhere) does not disavow Poetics of Location (to be here, where I am—now). Although Western modernity presents history as linear and centered in the West, negated knowledge(s) from many other parts of the world were never really buried; neither were they rendered impotent. Today, this knowledge is rising from the sidewalks, graves and footpaths where, for many centuries, it was relegated to the shadows of Western hegemony. Thus when we speak of “one world” today, it is no longer in a generalized sense for which the seat of hegemony is solely located in the Occident. One-world is a complex world wherein the notion of scale, distance, identity, and location are perpetually expanding and contracting, out of which myriad ways of being-in-the-world are generated.

The Invisible Borders project recognizes these tendencies and applies them accordingly to the notion of Africa: a story of many journeys and dispersals. The knowledge generated from the Invisible Borders project operates relationally. It preserves nothing of itself, neither does it aim to make a center of itself. It assumes the consistency of air as soon as it is let out into the world, yet it acknowledges that the experiences upon which it is generated are anchored to the context-specific realities, at the moment of encounter, of peoples, places, rivers, bridges, objects on the road in the corners of the world where the artists have set foot. The significance of the body and presence, feet touching the ground—to think on, and from the road—is at the core of the project’s decolonial premise.

It is for this reason that we have made our work readily accessible. From the onset of the project, we have generated a substantial amount of knowledge-materials, which today have a place in the cultural archive of our time and contributes to complicating the linearity of global language. More than sustaining a commendable string of online platforms and offline database, we have preserved this knowledge in every artist or art administrator who have so far participated in the project. In Dhaka, Kay Ugwuede, a writer and participant, was heard explaining to another colleague that “what we are attempting to do with the Invisible Borders Project is to humanize borders”. This description has remained––despite its brevity––the most loaded, in my opinion. It also sets the tone and focus on what is to come in the second decade of the project.

Emeka Okereke is a Nigerian visual artist and writer who lives and works between Lagos and Berlin, moving from one to the other on a frequent basis. A past member of the renowned Nigerian photography collective Depth of Field (DOF), he holds a bachelor’s/master’s degree from the Ecole Nationale supérieure des Beaux Arts de Paris and has exhibited in biennales and art festivals in cities across the world, notably Lagos, Bamako, Cape Town, London, Berlin, Bayreuth, Frankfurt, Nuremberg, Brussels, Johannesburg, New York, Washington, Barcelona, Seville, Madrid and Paris. In 2015, his work was exhibited at the 56th Venice Biennale, in the context of an installation titled A Trans-African Worldspace. Okereke has served as guest/visiting lecturer in several art platforms and learning institutions – most recently Hartford University’s MFA program in photography and Summer Academy of Fine Arts, Salzburg Austria (July 2018). In 2018, Emeka Okereke was conferred France’s prestigious insignia of Chevalier dans l’ordre des Arts et Lettres (Knight in the Order of Arts and Letters) by the Ministry of Culture of France as recognition of his contribution to the discourse on art in Africa, France, and the world at large.

Notes

[1] Invisible Borders Trans-African Photographers Organisation, “Mission,” https://invisible-borders.com/about/mission/.

[2] Walter D. Mignolo, The Darker Side of Western Modernity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[3] One of the main strategies, since the inception of the project in 2009, is to keep a daily blog while on the road. The entries consist of images, videos, essays, and audio recordings (podcasts). This has evolved into mobile apps. The same was the case for the 2018 road trip. See link: http://lagosmaputo.invisible-borders.com/lagosmaputo/recent.

[4] Emeka Okereke, “Transcending ‘Africa’: Diary of a Border Being,” published on May 2012, https://borderbeing.com/2012/05/16/transcending-africa/.

[5] Invisible Borders Trans-African Project, Lagos-Maputo Road Trip 2018, “Cameroun a Few Days After”, 2018, http://lagosmaputo.invisible-borders.com/lagosmaputo/post/cameroun-a-few-days-after.

[6] Chinua Achebe, The Education of a British-Protected Child (London: Penguin Books 2009), pp. 5-7.

[7] Toni Morrison, The Origin of Others (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), p. 30.