An Interview with Trinidad Ruiz

Noni Brynjolson

In October 2017 I spoke to Trinidad Ruiz, a community organizer, educator and programmer who has worked for a number of different arts organizations in Los Angeles, including Fulcrum Arts and Side Street Projects. As someone who works at the intersection of creativity, community building and tenant activism, he has a unique perspective on issues related to gentrification and displacement in the city. Our conversation focused on art, real estate and speculation in L.A., the role of art in relation to community organizing and activism, and how mainstream art institutions have sought to reach out to neighborhoods perceived as marginalized or underserved. We also discussed the role of artists who work as community organizers. Ruiz reflected on past experiences working on Watts House Project and with the tenant organization Union de Vecinos. We revisited our conversation in September 2019 in light of recent developments in Boyle Heights. What follows has been edited for clarity and length.

Noni Brynjolson: Can you tell me a little bit about the neighborhood you grew up in, and your relationship with L.A.? As someone who has lived here all your life, what changes have you noticed?

Trinidad Ruiz: I grew up in Santa Ana, California, but as a child my father would drive my mom and me to L.A. regularly. There’s a sign off of the 110 North, Felix the Cat, that car dealership, near USC. I knew when I saw that sign we were in Los Angeles. I don’t remember much of a difference between Los Angeles and Santa Ana to be honest. One of my earliest memories of L.A. was walking in the sawdust of the Grand Central Market, the smell of freshly cut wood, ripening fruit, carne asada saturating the air, my father buying me a bag of steamed peanuts. Those memories were similar to my memories of Santa Ana along 4th Street, where I would ride my bike from Lowell and Bishop Street to find a paletero, eat food, buy toys and comic books, speak Spanglish, and sit outside audio stores that blared mariachi and corridos.

In the late 90s, I lived in Downtown Santa Ana for a few years. The community was overwhelmingly Mexican. In fact, Santa Ana had the largest Mexican immigrant community north of Tijuana. At that time, there was a small art colony taking shape made up of a mix of Chicanxs and Whites. The Gypsy Den was the first artsy coffee shop that opened – they served crème brûlée instead of flan, espressos instead of café de olla. The Gypsy Den opened near the location of the soon-to-be-built Grand Central Art Center. A frame shop and a photography store opened on Broadway, next to a taqueria and dress store selling quinceañera and wedding dresses. The thing about gentrification is that the process looks almost exactly the same no matter where you go. I started to see the changes through the new businesses and galleries opening up. These new shops didn’t cater to the community that lived there. All that the Latinx community could do was shrug their shoulders and try to ignore the weird gringos. Gentrification hadn’t affected housing yet but it was only a matter of time before the seeds planted by the Gypsy Den and the galleries would begin to attract people with a lighter complexion and higher income. When a community lives on land that the rich and powerful want, colonization happens and Santa Ana would be no different. Despite all of our accumulated history, this process of dispossession, displacement, and injustice repeats itself over and over. Orange County cares about ownership – a very Republican ideal – and without any rights, it was easy for landlords and developers to simply raise rents and push people out. It has become more progressive but the housing laws have yet to catch up.

I moved to L.A. in 2000 to complete my education and fell in love with the city, I never left. Back then, L.A. was already experiencing pockets of gentrification due to galleries in places like Culver City, West Hollywood, and Venice Beach. Being that L.A. was so large, if rents got too high, you could move to another part of the city and pay less rent. After 2008, gentrification in Culver City, West Hollywood, and Venice Beach, started happening in Echo Park, MacArthur Park, Highland Park, South Central, El Sereno, Downtown L.A., Koreatown, Chinatown, Boyle Heights, East L.A. Suddenly Los Angles, a city that seemed so big that you could outrun the high rents, became small and deeply interconnected. When communities displaced in Culver City, West Hollywood and Venice Beach moved to places with lower rents it caused displacement and higher rents in those areas. When those communities that were evicted found affordable housing in other parts of the city, they ended up displacing the communities there, and on and on.

NB: What is your relationship with the arts community in L.A.? Do you see yourself as an artist, a community organizer, or both at once?

TR: What is an artist, what is an organizer? Are these roles incompatible or interchangeable? I thought of myself as an artist but now I perceive myself more as an organizer. The work of both do overlap in some cases – both are about connecting to community, growing value and agency, but they bifurcate when it comes to who benefits from this work. An artist exists within a capitalist framework and the work generated by an artist becomes a commodity, materialized through a range of mediums, and rarified. The artists themselves can inhabit that very space of commodification if you consider performance art. An organizer, on the other hand, connects with community outside of that capitalist framework. The work of an organizer is about valuing community itself, nullifying the power of capital, and eradicating exploitation through movement building. The currency of an organizer is awakening agency in marginalized and exploited communities, where none is perceived to exist by those in power. That then becomes political strength. Can an artist do similar work that impacts community without taking a paycheck? Sure, but they want authorship at the very least. The organizer doesn’t need authorship. If the work the artist does is about creating something of value in a community, creating something visually impactful, then it can be used as a tool for gentrification and we go back to what happened in Santa Ana, Boyle Heights, Highland Park, Culver City, etc. I return to the same question, the real difference between the artist and organizer is laid bare after asking: who benefits from the work?

As for the arts institutions in L.A., I’ve had the opportunity to work in some amazing places, from Orange County to L.A.: the Orange County Museum of Art, The Fowler Museum, the Hammer Museum, and MOCA, among a few others. There was a lot that didn’t sit well with me in the art world. After having worked within those institutions, I began to discover that there was a small circle of people who decide the value of an artist and the work: collectors, critics, museum directors, etc. It wasn’t until I started working alongside community in 2009 that I was able to diagnose how deep the problem went. I can understand why artists started to work outside the established and commercial world of art as commodity. Social practice, a movement among artists to work within communities, had already taken shape. In the case of my work in Watts, artists worked directly with homeowners around the Watts Towers and marshaled their skill sets to creatively reimagine a unique model of neighborhood revitalization. It was a huge departure from the traditional model of galleries and museums as centers of creativity. Now, artists were working directly in places that museums and galleries ignored. Although community organizing wasn’t in my job description, it was definitely a large part of the work, and that started to become more important than the art part of the project.

NB: As someone who has worked in a number of art museums, what changes have you noticed in their approach to outreach and community engagement over the past decade?

TR: There was a crisis of relevancy with this new movement of social practice and, in general, a move away from cultural institutions as places that define “high” culture. Most of the institutions I was at, aside from a few exceptions, the directors were all men. Another issue was the audience. Who was going to these museums? Not the kids in Watts, who live 3 or 4 miles from the beach but have never seen the ocean. Or kids from Boyle Heights, or from South Central. These institutions were designed for a certain audience and demographic that did not include communities of color, or the working classes. And I really started to see that. Most of the problem is that these institutions are also situated in places in the city that aren’t accessible to working class communities of color.

NB: Can you talk about your experiences working on Watts House Project? It received some criticisms, including that residents were promised certain repairs that didn’t end up happening, that there were issues due to the public-private nature of the project, and that it produced tensions in the community.

TR: When I began working at Watts House Project in 2009, I was just an assistant and helping with programs. It was not very organized, there was no infrastructure or accountability, and when an organization is doing the type of work that this project was doing, a lack of organization can be fatal. Sure, there were a lot of big ideas, but lack of funding and organization made following through on those ideas part of the reason projects took so long. The more aesthetic components happened faster than the interior of the homes. We learned that in construction there are always unforeseen issues and they can be expensive. Structural repairs on a home always ended up costing way more than expected. At one of the houses, contractors went in to the bathroom and said we had to redo all the plumbing, there were a lot of leaky pipes and rotting wood, and they had to replace it all. The interior projects were important to homeowners, but the aesthetic components were important for the public face of the project, and it was often difficult to strike a balance. For example, we would redesign the fence around some of the houses, and include benches so you could sit and enjoy the Watts Towers. The intent of installing benches was to engage the public, but this triggered all kinds of other issues with liability – what if someone sat on the bench and fell over and cracked their head open? Who would be liable? Well, the homeowner would be, it turns out, so we had to be careful. Nevertheless, there was a lot of energy to formulate great ideas in collaboration with the homeowners. We started big and scaled those ideas down as we faced challenges, including liability concerns, budget concerns, and capacity concerns. The projects would get smaller and smaller, or just didn’t happen. Another one of the big issues had to do with the practicalities of tax laws. There were promises made to the homeowners that the work would be gifts, and then the board realized, this can’t be a gift, it has to be a loan in perpetuity, so if they sell the house they only get back what they invested into it. But the homeowners took that as a betrayal because a “gift” had already been promised to them. That created a huge rift, and that was the other huge problem with the project. It was all big ideas – all frosting and no cake. And then another issue was that the Watts Towers Art Center was not supportive, and they saw the project as coming from outside of the community.

NB: What were some of the positive outcomes of the project, in your opinion?

TR: The idea was to improve the aesthetics of the neighborhood, with the idea that visitors to the Towers might actually come and engage the families on the street, and realize Watts isn’t this dangerous neighborhood. So the project was a way for families in the neighborhood to engage with the general public. A lot of the work was built around volunteering and getting neighbors to help each other. There were weekly meetings at the Watts House Project site, and there were neighbors that would come out to help other neighbors. That was one of the things that was really cool about the project – it would bring people out in a way that wasn’t happening before. I was told by the community that no one knew each other before the project. They would wave and say hi but that’s it. That’s what community organizers do, they get people talking, and they encourage neighbors to help neighbors. There was a roofer on the block and after the project began he would help his neighbors fix their leaky roofs. Another man was a welder and he helped with wrought iron work. So there was an exchange of services that developed, and sometimes they would hire each other. In this sense, I think it was a project that built community, and that ultimately became its legacy, but you can’t see that, you can’t put it in a museum, you can’t buy that or collect it.

NB: Some of the things you’ve been discussing are common within social practice, in which artists attempt to orchestrate social relations in a particular place, or produce useful services in communities. Do you identify with the label ‘social practice artist?’

TR: I don’t know… I think that a lot of artists have been slowly moving into that field of community organizing. When you’re coming out of major art institutions and universities, the whole point is to step into the speculative economy as an artist and make money. When these same artists are helicoptering into communities applying that same model, that should be criminal. When artists become social practitioners they have a responsibility to communities to do no harm. That might mean not doing a particular project. If it means that they become organizers, and give up the idea of authorship and commodification to creatively engage communities, this is work that can become useful. For instance, painting protest signs or other subversive art works meant to recalibrate power dynamics – so that people thought to have none, actually realize they do – that’s art worth doing in communities. When I was working on Watts House Project, the point was to create these beautiful projects in and around the home – to improve quality of life for the residents – but it also became about building community. I think that both artists and community organizers have the ability to engage community and work on specific causes but it goes back to the same dividing line – who benefits? The problem with social practice artists is that they don’t take their own egos out of it – there’s a need to create authorship. When the artists become the focus of the work happening in communities that they don’t live in, then social practice is exposed as nothing more than a vehicle to create value for the artist, on the backs of the less fortunate. Organizers, they’re nameless – some personalities do stand out, but generally they’re less interested in taking credit. Being on both sides of this has been fascinating, and seeing examples of social practice art becoming tarred with “artwashing” and exposed as a tool for developers and gentrification. This has taken a lot of the shine off of this type of work. If you’re an artist doing social practice work in communities and you’re not questioning and analyzing every single thing you’re doing, then there’s something really wrong with the work. Again, it’s going back to that old model of capital and speculation where developers gentrify and the artist creates value with their name or brand. I ultimately decided to leave the art world, all that drama, all that fake shit, and went to work with community.

NB: Thinking about your experience with Watts House Project, what lessons have you learned? What could be applied to thinking about other neighborhoods, like Boyle Heights?

TR: Looking back on Watts House Project, I’ve kind of thought, maybe the Watts Towers Art Center had a point. When galleries or arts organizations come into a community from outside, they can be seen as helicoptering in with their own agenda. I see somewhat of a similar dynamic in Boyle Heights, with activists trying to fight these galleries with everything in their arsenal, going to the press, doing everything they possibly can, similarly to what the Watts Towers Art Center was doing to us. I also think that there were some really important developments that came out of the project in Watts, like encouraging neighbors to share skills, and this is noticeable in Boyle Heights, too. There are skill sets that people contribute to the campaign against galleries, and to neighborhood improvement efforts, like builders and painters. For instance, some residents in Boyle Heights had a problem with dog poop on the sidewalks, and the community got together and said let’s do something about it. They created sturdy “pick up after your dog” signs in Spanish and English. That was exactly the kind of work that Watts House Project was attempting to do – instead, these artistic interventions originated in the community and not from the creative mind of an artist. The difference is that in Watts you had Edgar Arceneaux as a big time artist, but Union de Vecinos is not attracting the same kind of attention.

NB: Can you tell me about your work with Union de Vecinos?

TR: I worked there from 2015 to 2019, and the organization has been around since 1996. It was formed after the closing of the Pico Aliso public housing project, when 900 residents were displaced. So the majority of the work is focused around housing, but they also do environmental issues, neighborhood safety, popular education, they educate tenants about their rights, they work with unions, and various housing rights organizations. They have a headquarters, but most of the work happens in the community, it’s decentralized. They help organize resident committees, which are maybe about a square block radius, and these are made up of all the people who live in that area. They have weekly meetings led by organizers, and they talk about local issues. So there’s Hollenbeck Committee, there’s Bienestar, there’s Cesar Chavez, there’s Estrella Committee. Some of these neighborhood committees formed to address issues with alleys – there was prostitution and drug dealing, and tenants created various interventions to change the dynamic. They paid for and built benches and installed solar powered lights. They wanted to create a space for community to gather, so it was safe for everyone. On some streets, like Bienestar, there were high speed cars going through and the committee lobbied the city to create speed bumps to make it safer. But the aim of Union de Vecinos has really been to bring neighborhood residents and tenants into the fold. Meetings are held at somebody’s house, and are focused on residents of Boyle Heights talking together about the issues facing their community, like rent protection, and gentrification caused by galleries. Union de Vecinos also organizes larger events – they have gone to City Hall to attend meetings, organized protest actions, press events and sit-ins. Their aim is to do whatever they can to disrupt how power is exerted on communities, and instead, to exert their own power as a community.

NB: What do you think these types of organizations can do? Do you think they’ve been able to effectively put pressure on the city, or on local developers?

TR: One of the things we were doing was going after local property owners. We were going to their houses, to the neighborhoods they live in, to protest, and we were doing this to politicians as well. It was one of our tactics. Ultimately, we were creating an environment in which ignoring and doing nothing about housing issues was untenable, and that put political pressure on politicians. Movement building doesn’t happen by staying home and hoping for change. We have plenty of examples in history that have shown us the way: the Civil Rights movement of the 60s, LGBTQ rights, Suffrage, the Chicanx movement, etc. For private developers, exposing the rent gouging and slumminess of their buildings makes unethical and illegal behavior more of a liability for them. These developers hide in the shadows, behind LLCs, LP, Trusts, and other financial barriers. Exposing them means learning about the various boards they’re on, churches they attend. When your neighbors in Hancock Park, Brentwood, Malibu or Beverly Hills learn that they’re living next door to a person who would rather evict a 70 or 80 year old onto the streets where this person will die, just to make an extra dollar, it changes everything.

NB: What role have you seen artists play in some of the social movements against displacement in Boyle Heights?

TR: There are a handful of artists involved, and they’re really active and vocal. They bring creativity and their own aesthetics to these movements. There are also community members who have no training in visual arts involved in the process of visualizing the issue of gentrification, and they sometimes see it differently than artists. I think the real energy comes from the community. In the Guardian article that came out about Boyle Heights, the activists were all portrayed as white, middle-class artists.[1] I really disagreed – it focused too much on people’s backgrounds when it should have been about the issues. But what is really interesting is that some of the artists involved in the protests know the artists on the gallery side, and some of them are friends, or were friends. I knew people on the board of PSSST, for example, who called me because I worked in the art world, and they wanted Latino people on the board so it didn’t look like a bunch of white hipster artists coming into the neighborhood to gentrify it. To me, this felt similar to Edgar going into Watts not really knowing the community. Same thing here. A lot of the artists and gallery owners didn’t come to Boyle Heights knowing the community, and that’s what I warned my friend about – I told him that this is a community that’s been organizing for decades, and for multiple generations, and it’s going to get ugly.

NB: So what would you say to artists who argue that they’ve been priced out of neighborhoods like the Arts District, and they have nowhere else to go but low-income neighborhoods like Boyle Heights?

TR: Although artists are considered a force for gentrification, let’s be frank, they’re tenants too and it all goes back to a lack of tenant rights. This is what the L.A. Tenants Union has been arguing: we need renter protections and this is the real crisis in L.A. – a lack of renters’ rights. If you examine what’s happening now, there’s an eviction crisis despite a high percentage of vacancy rates downtown and across the city. Apartments aren’t being filled because they’re too expensive. For buildings that are RSO (rent stabilized), older property owners die, or they cash out by selling for several million. Tenants who live in these buildings have been there for 20-30 years sometimes, paying $700-800 for a one bedroom, and they are suddenly at the mercy of developers incentivized to evict them using the Ellis Act who can bring in $3000 a month from that same one bedroom. A developer wants to make money off of the building that they overpaid for, and without renters’ rights and protections, they evict everyone, including artists. If there were renter protections or even a change in the amount of relocation amounts or vacancy control, then maybe developers would think twice about the incentive to displace working class POC families, and elderly people on the streets. For the elderly and retired, it’s especially lethal to get evicted. They’re earning just social security and that might be $1500 a month but they’re paying $500 in rent. When they’re evicted, where do they move to? Some artists evicted from the Arts District, on the other hand, moved to Boyle Heights for more affordable rent pushing out these same families. L.A. is a city that is profoundly connected, in terms of neighborhoods.

NB: Where are people getting displaced to?

TR: Most of the working class families are moving to Riverside, Menifee, they’re moving to the desert, closer to places like Antelope Valley, where there are fewer services and no public transportation. It’s either that, or the streets of L.A. There is a vicious cycle of displacement and homelessness in this city. For people who have lived here for 30 years, lived through the worst times in L.A., then suddenly priced out or evicted, the only choice is to find a place with lower rents and that seems to be farther and farther east. I’ll say this – displacement means more than just relocating to the desert. It means leaving your support network, jobs, friends, grocery store, doctors, schools, family. It’s devastating. Displacement is an issue that goes beyond housing.

NB: How do you think speculation and art-related development are affecting Boyle Heights right now?

TR: Speculation doesn’t happen without a trigger, and in Boyle Heights the trigger has been the galleries. Property owners, LLCs and multinationals are going in and buying these buildings, and fixing them up to make them appealing for someone who can afford the rent. We have this one guy, Brian Newman, an owner who bought a building, right where 6th Street Bridge is being built. Latino residents who lived there and were paying $700 for a one bedroom have been asked to leave, and it’s clear that he would prefer white artists to live there – he actually said it himself to tenants and organizers. One of the first questions he asked the tenants after purchasing the building was “do you have papers?” Some people didn’t and they moved immediately, just disappeared. Real estate and art live and die off of speculation. It’s the driving force in both markets. Maybe that’s why they’re so interrelated. Artists raise the property values because they make a neighborhood ‘cool’ to live in. Perception is everything when it comes to art and land. In this country, someone with money can force you to move away from the place you live, and the only motivation for that is to cash in on the perceived value of property. To me, this sounds a lot like colonization. The laissez-faire L.A. city government can continue to count on seeing tens of thousands of the growing unhoused until they address the lack of tenants’ rights head on.

NB: Can you talk a little bit more about the art that is made in Boyle Heights outside of the galleries and official art spaces?

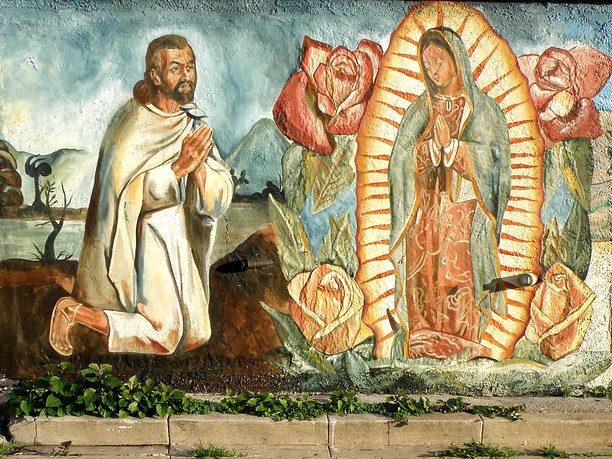

TR: Boyle Heights has a long tradition of murals, mariachis, poets, singers – it’s a truly vibrant artistic community born from its cultural roots and history. The galleries that moved in claimed to bring the culture. Which is all bullshit. What they were bringing was an economic, capitalistic model of land speculation that has resulted in displacement. But the culture of Boyle Heights is about the community asserting itself to reclaim space. When you visit Boyle Heights today you’ll see lots of murals of the Virgin of Guadulupe. Union de Vecinos, along with the community, helped paint many of these murals in the 90s because the gang bangers respected that image. Those walls were usually left alone with no graffiti. Want a wall safe from tagging? Paint a mural of the Virgin and those walls are left untouched. If you think about it, this is the real social practice.

Trinidad Ruiz is a Chicano, an avid cyclist, visual artist, community organizer, educator, programmer and collaborator. He is currently Programs Manager at Fulcrum Arts, “an art service organization originally formed in 1964 to provide resources, communication services and other support to artists, cultural organizations, audiences and visitors.” He is also Communications Manager at Side Street Projects, a completely mobile arts organization that delivers arts resources directly to diverse and underserved communities and schools with programs that weave together problem-solving, creativity and skill sharing. Ruiz was previously Director of Sustainability & Storytelling for People Organized for Westside Renewal (POWER) and Union de Vecinos. He was also Programs Director at Watts House Project where he managed programs and projects that re-interpreted the ecology in Watts to benefit community through partnerships between creative professionals and residents. Ruiz received a BA in Art History and a Minor in Chicano/a Studies from UCLA, as well as an AA in Studio Art.

Noni Brynjolson is an Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Indianapolis and a member of FIELD‘s editorial collective.

Notes:

[1] Rory Carroll, “Are white hipsters hijacking an anti-gentrification fight in Los Angeles?” The Guardian, October 18, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/oct/18/los-angeles-gentrification-boyle-heights-race-activism