Digital Highway Becomes Digital Jail

Katatare Prajapati Collective

Despite the passing of 47 years since its independence, and various efforts to institutionalize democracy, Bangladesh has never embraced the tenet of freedom of expression. Free speech, as enshrined under Article 39 of its Constitution, remains a highly qualified right and is subjected to some notable restrictions.[1] Although the current Awami League government won the 2008 election partially on the popular pledge to build “Digital Bangladesh,” in the last few years a draconian law, and its indiscriminate application, have made digital speech a heavily policed and punished area. This is manifested in the controversial Section 57 of the Information and Communication Technology Act (2006, amended in 2013), and the wider provisions in the forthcoming Digital Security Act (2018).

According to Human Rights Watch, between 2013 and April 2018, the police submitted 1,271 charge-sheets against journalists and private citizens, most of them under section 57 of the Act and with many of the cases involving multiple accused.[2] In July 2017, a Bangladesh Public Prosecutor told journalists that trials in 400 cases filed under Section 57 had begun.[3] Human Rights Watch published a list of recent cases filed under Section 57, which highlights the rise in digital prosecution, which corresponds with the increase in the use of internet in the country.[4] As noted in positive reports of technological breakthroughs, Bangladesh has one of the highest rates of internet usage, and Dhaka, with 22 million active Facebook users, is the second highest Facebooking city in the world.[5] Therefore, we see that digital literacy is followed by digital prosecution, and the information highway is becoming a surveillance and prison grid.

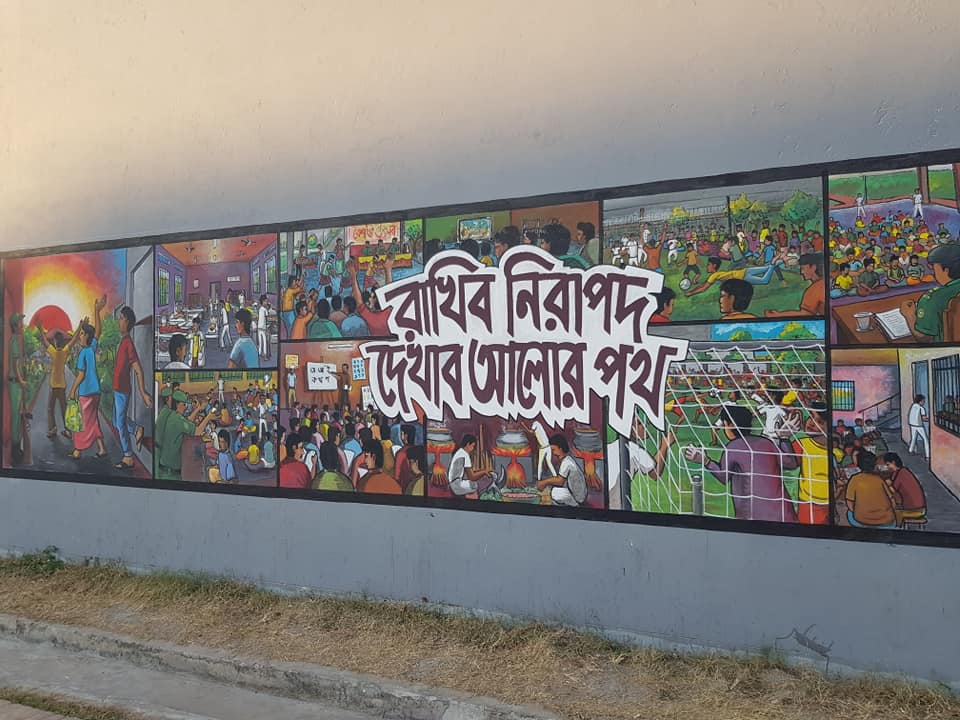

Even prior to the spread of digital literacy and the full expansion of Section 57, the court systems were frequently used to curb speech and traditional journalism. In a two week period in 2016, 67 criminal defamation cases and 16 sedition cases were filed by private citizens against Mahfuz Anam, editor of Bangladesh’s largest English newspaper The Daily Star.[6] The largest Bengali newspaper, Prothom Alo, has faced more than 100 criminal cases against its staff since 2013, half of them still waiting resolution in the court system. One special aspect of prosecutions under Section 57 is that not only the police and other state agencies can bring a case, but so can private citizens. This last aspect is vulnerable to wide abuse, as personal grudges can be settled under this loophole. Cases have been filed by private citizens under Section 57 against academics such as Professor Afsan Chowdhury, co-editor of an eleven volume history of the Bangladesh liberation war, for alleged remarks on Facebook.[7] Most recently, the “remand” detention of actress Nawshaba,[8] and the nighttime abduction and next day arrest of photographer Shahidul Alam, were for online comments on the “Safe Roads” student protests.[9] Arrests were made, under other laws, of student protesters from the “Safe Roads” movement, and the earlier “Quota Reform Movement.”[10]

Successive administrations in Bangladesh have had antagonistic relationships with the media, journalists, civil society actors and even private citizens critical of the government. This was evident when the Bangladesh Nationalist Party(BNP)/Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) rightist-islamic coalition was in power between 2001 and 2006, with journalists being charged with criminal defamation, and sedition cases filed against civil society members. Similarly, under a military-backed caretaker government (CTG) in 2006-2008, the Emergency Powers Rules allowed legal action to be taken against media critics,[11] and the military’s intelligence wing, the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), is known to have used threats and intimidation against journalists critical of the administration.[12]

The end of military rule, and the electoral victory, that brought the Awami League to office in 2008 did not bring any change in this antagonistic landscape. Instead, by 2009, especially after the brutal bloodshed of the Bangladesh Rifles mutiny, social tension was again escalating and the space for criticism and dissent shrinking rapidly.[13] By 2010, there was concern that the DGFI, already a significant factor in the period of BNP (2001-06) and CTG (2007-08), was exerting influence to reduce critical commentary in the media, and journalists and newspaper editors were being threatened for criticizing the government or military.[14] Several television channels were also shut down by the state regulatory body.

The Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT) of 2006 has been part of the current administration’s policy to integrate digital communication and technology at the national and local levels with its very admirable, and essential, goal of advancing technological development. But beyond the development objective, the Act was also drafted to serve as the primary legal reference for matters related to internet access, and to define freedom of expression online, cover crimes committed through electronic means that do not come under the Penal Code and other legislation, and regulate digital communications. For instance, by defining hacking as a crime punishable by up to three years in prison or a fine of 10,000,000 Bangladeshi taka ($125,000) or both, the Act recognized the rights of citizens whose rights to communicate electronically have been violated by others.[15] The possible role of the Act in undermining freedom of expression and speech has caused alarm. One section of the law, Section 57, has been most controversial. This is the section under which various people have been charged recently.

Section 57 (now integrated into the newly passed Digital Security Act) “authorizes the prosecution of any person who publishes, in electronic form, material that is fake and obscene; defamatory; ‘tends to deprave and corrupt’ its audience; causes, or may cause, ‘deterioration in law and order’; prejudices the image of the state or a person; or ‘causes or may cause hurt to religious belief’”.[16] The vagueness of the premises of violations outlined here are disconcerting enough, but political developments in Bangladesh and the subsequent use of Section 57 by state and non-state actors have been even more troubling. In 2012, gangs of men organized via social networks attacked the Buddhist minority community and destroyed their temples in Ramu village, following false accusations against a Buddhist man of defamation of Prophet Mohammed on Facebook.[17] Similar attacks against Hindu minorities took place in 2013 in the town of Santhia following the use of a fake Facebook account to create the pretext for premeditated attacks.[18]

Finally, there were the events surrounding the 2013 Shahbag movement, which was mobilized through social media and centered around the demand for the death penalty for war criminals of the 1971 Liberation War. While initially a non-violent movement that attracted citizens from all social, economic and political backgrounds, the killing of a Shahbag blogger derailed the moment.[19] The death led to protests by Shahbag activists, a counter-mobilization and violent street attacks by an affiliation of madrasas called Hefazat-e-Islam that accused the Shahbag activists of being “anti-Islam”. Various Islamist groups began creating lists of “atheist” bloggers,[20] leading to a spiral of vigilante murders of secular bloggers and LGBTQ activists.[21]

Against this turbulent backdrop within which misinformation and unverified images were spread through social media, the government amended the Information and Communication Technology Act, eliminating the need for arrest warrants and official permission to prosecute, restricting bail, and increasing prison terms to 14 years. Under this 2013 amendment, a person could be arrested on the basis of a complaint to the police, regardless of whether the person filing it had themselves been prejudiced, defamed or otherwise “injured” by the offending material. This opened the door for arrests to be made for any statement that could be interpreted by any citizen as critical of the Prime Minister or her family.[22] The Act also instituted a Cyber Tribunal to solely deal with offenses under the law.

In a large irony of recent Bangladesh history, the amendment to the ICT Act was initially inspired by communal riots and targeted violence against Indigenous Buddhist Jumma people (Ramu, 2012), the Hindu community (Santhia, 2013), the secular Shahbag bloggers, and LGBTQ activists (2013-2015). Yet, since its passage, the amendment has rarely, if ever, been used against forms of hate speech and violence directed against minority Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, or Adivasi communities. Instead, it has most been used against secular activists, bloggers, journalists, photographers, and academics. The amended Act was used in April 2013 after a list of eighty alleged violators had been drawn up by a social committee formed by the government that included several Muslim clerics. It led to the arrest of four bloggers who had expressed their opinions on religious extremism on social media and were members of the Shahbag mobilization. Other detentions and arrests of bloggers, Facebook users, journalists and civil society activists who had criticized the government on social media or in the press followed. The majority of the charges involve criticism of the government, defamation, or offending religious sentiments, while the rest are allegations against men publishing intimate photographs of women without their consent.

In addition to frequently using Section 57, which has resulted in the suppression of diverse opinions in the digital space, authorities in Bangladesh have also blocked Facebook,[23] YouTube and other social network platforms without prior notification on multiple occasions.[24] There has been severe criticism of the Information and Communication Technology Act, and Sections 56 and 57 in particular, on the grounds that they challenge Article 39 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression. In 2015, prominent members of civil society filed a High Court petition against Section 57 alleging that it violated freedom of expression and had created a hostile environment that promoted self-censorship among bloggers, journalists and citizens.[25] In 2017, following public outrage at the arrest of a reporter for a Facebook post in Khulna district, the Bangladesh government proposed replacing the Information and Communication Technology Act with the Digital Security Act. Comprising 36 sections, the new Act has not yet been passed by Parliament although it has been approved by cabinet. If it becomes law, it would mean that Sections 54, 55, 56, 57 and 66 of the Information and Communication Technology Act would be technically “repealed.” But critics have expressed alarm about the draft law, claiming it is simply a redistribution of the disturbing provisions of Section 57 into four sections (21, 25, 28 and 29) and is in fact more far-reaching and draconian than its predecessor.[26] In January 2018, the cabinet secretary stated that the Digital Security Act was not designed to target journalists.[27] But journalists have argued that the provisions that treat “the use of secret recordings to expose corruption and other crimes as espionage” would “restrict investigative journalism and muzzle media freedom”.[28]

There are concerns about other provisions too. Section 21 of the new bill proposes a 14-year jail term for anyone convicted of “negative propaganda and campaign against liberation war of Bangladesh or spirit of the liberation war or Father of the Nation”. Section 25 (a) states that publishing information that is “aggressive or frightening” is punishable by up to three years in prison, without defining how such determinations would be made. Section 28, which deals with speech that would be considered to “injure religious feelings” and carries a prison term of up to five years, requires proof of intent. The abuse of such a provision to target citizens in the context of Bangladesh raises significant concern. Section 29 focuses on online defamation but, unlike the Information and Communication Technology Act, limits such charges to those that meet the requirements of the criminal defamation provisions of the Penal Code. But this still runs contrary to a growing argument in the country that defamation should be treated as a civil matter and not as a crime carrying a prison sentence.[29] Section 31 says posting information that “ruins communal harmony or creates instability or disorder or disturbs or is about to disturb the law and order situation,” and speech that “creates animosity, hatred or antipathy among the various classes and communities”, would carry a prison term of up to 10 years.[30] But it does not clearly define what kind of speech would be considered a threat to “communal harmony” or one that would “create instability”.

As the space for dissent narrows in neighboring India and Pakistan, Bangladesh, in its efforts to remain a democracy, should be vigilant of the slippery slope of gagging fundamental rights and freedoms in the name of “law and order” using draconian legislation. While repealing Section 57 would be a step in the right direction, implementing the Digital Security Act with its existing flaws would usher in fresh crises. The current trend of silencing its citizens through legal intimidation does not bode well for the country’s democracy. Can the government step back from the temptations of narrowing the space for public discourse, and instead step forward to harness digital technology to advance the achievements, grow the economy, and increase social stability of Bangladesh?

Katatare Prajapati is a collective of Bangladeshi writers, photographers, and filmmakers. The name, which is Bangla for “butterfly on barbed wire,” comes from a 1989 Selina Hossain novel. They have made work about the long-running campaign led by leftist political parties to stop construction of the Indian-funded Rampal Coal Plant on the margins of the Sunderbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest, which spans Bangladesh and India.

Notes

1. Asadullahil Galib, “Section 57 of the ICT Act and Right to Freedom of Expression: Seeking the Balance Within,” The FutureLaw Initiative, August 9, 2017 https://futrlaw.org/section-57-freedom-of-speech-balance/ [viewed August 10, 2018]

2. “No Place for Criticism: Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/09/no-place-criticism/bangladesh-crackdown-social-media-commentary [viewed August 10, 2018]

3. Udisa Islam, “What Will Happen to the Section 57 Cases?” Dhaka Tribune, July 13, 2017 https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/law-rights/2017/07/13/will-happen-section-57-cases [viewed August 10, 2018]

4. “No Place for Criticism: Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/09/no-place-criticism/bangladesh-crackdown-social-media-commentary [viewed August 10, 2018]

Also see: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/bangladesh0518_annex_0.pdf

5. Mahmud Murad, “Dhaka Ranked Second in Number of Active Facebook Users,” BDNews24.com, April 15, 2017 https://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/2017/04/15/dhaka-ranked-second-in-number-of-active-facebook-users [viewed August 10, 2018]

6. Michael Safi, “Bangladeshi Editor Who Faced 83 Lawsuits Says Press Freedom Under Threat,” The Guardian, May 18, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/may/18/it-all-depends-on-how-i-behave-press-freedom-under-threat-in-bangladesh [viewed August 10, 2018]

7. “Afsan Chowdhury Gets Bail In Case Under Sec 57,” New Age, July 11, 2017 http://www.newagebd.net/article/19443/afsan-chowdhury-gets-bail-in-case-under-sec-57 [viewed August 10, 2018]

8. “Nawshaba Remanded Again,” The Daily Star, August 11, 2018 https://www.thedailystar.net/news/city/nawshaba-remanded-again-1618792 [viewed August 12, 2018]

9. “Bangladesh: Photographer Shahidul Alam Detained For Posts Supporting Student Protests, Say Reports,” Scroll.In, August 6, 2018 https://scroll.in/latest/889366/bangladesh-photographer-shahidul-alam-detained-over-posts-supporting-student-protests-say-reports [viewed on August 12, 2018] Also see: https://scroll.in/article/889351/as-dhaka-student-movement-for-safe-roads-turns-violent-protestors-and-government-trade-charges

10. “Quota Reform Leaders Fear Arrest, Enforced Disappearance,” Prothom Alo, July 4, 2018 https://en.prothomalo.com/bangladesh/news/179095/Quota-reform-leaders-fear-arrest-enforced [viewed August 14, 2018]

11. “The Torture of Tasneem Khalil: How the Bangladesh Military Abuses Its Power under the State of Emergency,” Human Rights Watch, February 13, 2008 https://www.hrw.org/report/2008/02/13/torture-tasneem-khalil/how-bangladesh-military-abuses-its-power-under-state [viewed August 14, 2018]. Also see: www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JlALawTA/2008/9.pdf.

12. Ibid.

13. “Bangladesh to Execute 152 Soldiers for Mutiny Crimes,” BBC World News, November 5, 2013 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-24817887 [viewed August 14, 2018]. Also see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bangladesh_Rifles_revolt.

14. “No Place for Criticism: Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/09/no-place-criticism/bangladesh-crackdown-social-media-commentary [viewed August 10, 2018]

15. “Bangladesh: Freedom on the Net,” Freedom House, 2014 https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/Bangladesh.pdf [viewed August 14, 2018]

16. Ibid.

17. Kaberi Gayen, “A Known Compromise, A Known Darkness: ‘Ramu-nisation’ of Bangladesh,” Forum, Volume 6, Issue 11, (November 2012) http://archive.thedailystar.net/forum/2012/November/known.htm [viewed August 10, 2018]

18. “Ramu Attack a Santhia Rerun,” BDNews24.com, November 8, 2013 https://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/2013/11/08/ramu-attack-a-santhia-rerun [viewed August 10, 2018]

19. “Two Sentenced to Death for Bangladesh Blogger Murder,” The Guardian, December 31, 2015 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/31/two-sentenced-death-bangladesh-blogger-ahmed-rajib-haider [viewed on August 10, 2018]

20. Samanth Subramanian, “The Hit List: The Islamist War on Secular Bloggers In Bangladesh,” The New Yorker, December 21 and 25, 2015 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/12/21/the-hit-list [viewed August 14, 2018]

21. Mukul Devichand, “‘Nowhere Is Safe’: Behind The Bangladesh Blogger Murders,” BBC World News, November 7, 2015 https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-33822674 [viewed August 14, 2018]. Also see: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/08/world/asia/bangladesh-secular-activist-killed-nazim-uddin.html

22. “No Place for Criticism: Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/09/no-place-criticism/bangladesh-crackdown-social-media-commentary [viewed August 10, 2018]

23. “Bangladesh Death Sentences Lead to Facebook Ban,” BBC World News, November 18, 2015 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-34860667 [viewed August 12, 2018]

24. “Bangladesh Plans to Block Facebook for Six Hours from Midnight,” BDNews24.com, April 3, 2017 https://bdnews24.com/technology/2017/04/03/bangladesh-government-wants-to-block-facebook-for-six-hours-everyday [viewed August 14, 2018]

25. “No Place for Criticism: Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/09/no-place-criticism/bangladesh-crackdown-social-media-commentary [viewed August 10, 2018]

26. “Digital Security Bill Placed in JS Amid Concern,” The Daily Star, April 10, 2018 https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/digital-security-bill-placed-js-amid-concern-1560637 [viewed August 14, 2018]

27. “Digital Security Act Draft Approved, Section 57 Repealed,” Dhaka Tribune, January 29, 2018 https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/law-rights/2018/01/29/digital-draft-cabinet-approval/ [viewed August 14, 2018]

28. “Bangladesh: Protect Freedom of Expression: Repeal Draconian Section 57 but New Law Should Not Replicate Abuses,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/05/09/bangladesh-protect-freedom-expression [viewed on August 14, 2018]

29. “Bangladesh: Scrap Draconian Elements of Digital Security Act: Cabinet Approves New Law That is Overly Broad and Ripe for Abuse,” Human Rights Watch, February 22, 2018 https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/02/22/bangladesh-scrap-draconian-elements-digital-security-act [viewed on August 14, 2018]

30. Ibid.