Artistic Protest Practices in Serbia

Rena Rädle

In this article I will give a brief overview of artistic protest practices in Serbia at the time of the normalization of an authoritarian right-wing government. As such practice can’t be treated apart from the struggles it is linked to, I will also explain the social context out of which these practices emerged.

After almost two decades of economic and legal reforms, with the aim of transforming this formerly socialist country into a potential member state of the European Union, the majority of the population lives in poverty. A small oligarchy has established itself and, together with the government and international investors, sells out the remaining resources of the country. The majority of the population works for wages below the existential minimum. While the first wave of privatization mostly left industrial workers without jobs, the recent measures, involving the privatization of communal services, have also effected the academically educated middle class and city dwellers, amongst them art and cultural workers. During the last few years, mainly in the bigger cities, citizens organized to address the devastating effects of the neoliberal reforms, with a special focus on the privatization of communal services such as energy and water supply, waste, public transport, health services, the educational system and the commercialization of city space. Along with protesting against the privatization of public and common goods, pauperization and precariazation, these movements express a deep concern about the political system of a form of ostensibly liberal democracy that proves to be non-representative and corrupt. Their response is to advocate for social justice, political participation and organization in a horizontal way.

Let’s narrow the focus to the arts now. The context in which art is produced in Serbia is constituted by ruined and dysfunctional national institutions (the art academies, the museums of contemporary art, the city cultural centers or galleries), project-oriented NGO’s with short-lived interests, emerging art market oriented galleries linked to obscure businesses and since recently—the Orthodox church. While cultural politics have not directly been the focus of state policy reforms so far, the current autocratic right-wing government is attacking the autonomy of cultural and educational institutions as part of a “culture war” waged against any kind of opposition and alternative to its leadership. The manifesto of this strategy is a policy document published in 2017 that includes a list of criteria that define Serbian culture. The program, along with encouraging liberal values such as cultural minority rights and cultural entrepreneurship, promotes an ethno-national understanding of culture and prescribes a catalog of precise criteria outlining what is to be considered Serbian art and culture. It is supposed to be rooted in folklore, ethno-national myths, and ethno-national hardship that have historically formed a “Serbian national identity,” which needs to be “defended from globalization.” The second pillar of right-wing cultural policy is the state-funded commercialization of art and production, with the aim to transform culture into profit-generating creative industries. Although the policy document is not yet officially adopted, in 2018 state funding was significantly reduced for independent actors and channeled to exponents of ethno-culture and commercial actors.

The take-over of art institutions by actors who are loyal to the new strategy has not passed without protests by artists. The first protest took place at the opening of an exhibition of Damian Hirst’s work titled “New Religion” at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina (MSUV) in Novi Sad in 2016. A group of artists and activists carrying posters with slogans such as “No to corporate culture,” “No to servile institutions,” and “No to bourgeois art,” entered the hall of the museum, distributed flyers and tried to hold a speech. They were interrupted and violently removed by private security. Hirst’s exhibition was the biggest ever held in Novi Sad, and it was publicly funded with an amount equaling one third of the annual program budget of the entire museum [1]. It was criticized on several levels: first, as an example of a neocolonial relationship towards a public institution, because the touring exhibition was organized by British Council and imposed by the ministry; and second, as an exploitation of public resources with the aim of promoting a corporate model of artistic production within the market of speculative financial capital.

This protest needs to be seen in the context of a growing awareness amongst art and cultural workers, students and academics in Serbia that public institutions need to be transformed into places where art and culture are produced and shared as a common good. Shortly before the Hirst protests artists and curators organized “F.A.C.K. MSUV”[2], a kind of soft occupation of the museum involving the staff, in order to try out a plenum-based model for the development of the museum’s programming, at least within a limited time frame.

While a relatively young institution like the MSUV could give space to self-organized programs such as F.A.C.K. MSUV or COLD WALL [3], which are both situated in a wider left movement, the older Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade (MSUB) never embraced such artistic practices. Founded in 1965 after the model of MoMA in New York, MSUB was basically a showroom of Yugoslav modernism aimed at culturally validating the nation’s estrangement from the Soviet Union and secondarily at demonstrating to all other countries a dedication to Western modernization. [4] Public discussion and negotiation about the function of MSUB within society were put on hold over the ten years of its closure. During this hiatus the museum staff failed to design a new role for Belgrade’s museum of contemporary art that would give space to a contemporary critique of hegemonic discourses in Serbia. Therefore it is no surprise that the much anticipated re-opening of the museum in autumn 2017 revealed a curatorial outlook that was entirely in line with the ministry’s new right-wing cultural strategy, and that it was overshadowed by violent police repression against protesting artists.

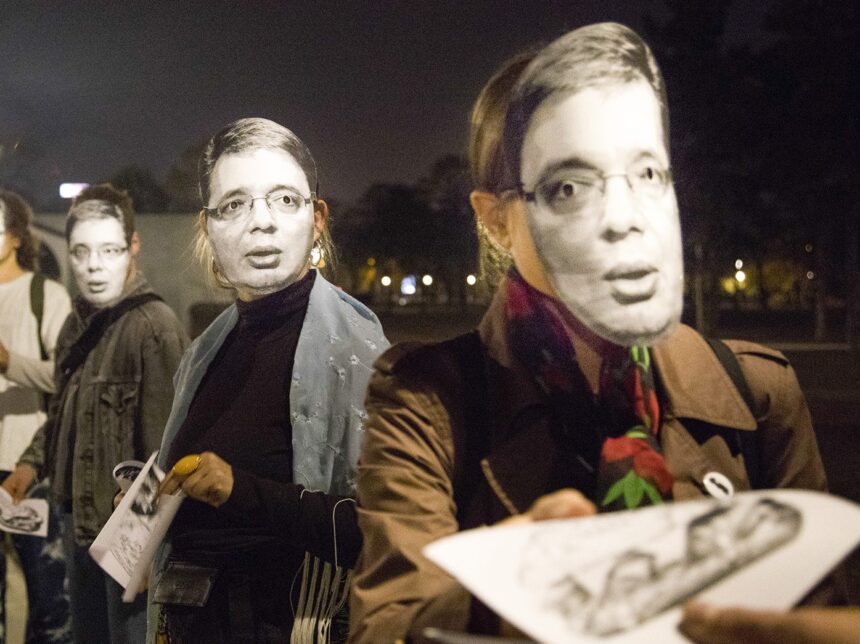

For the day of the opening, the group “The Unbribables” [5] had prepared a media campaign and exhibition program designed to protest the ethnification and commercialization of culture. They launched the program with an artistic action in which they wore masks with the image of the Serbian president and handed-out photocopies of sandwiches to the visitors in front of the museum, alluding to the common practice of political parties in Serbia of buying votes and employing supporters in party-controlled enterprises (so-called “sendwichari”). The performance was intended to symbolize the participation of the majority of the population in a system of corruption and blackmailing, while struggling for daily existence in an economically devastated country. One member of the group, Vladan Jeremic, was soon arrested. Uros Jovanovic, an independent artist and performer, experienced this same reality only half an hour later. He was arrested when he tried to enter the museum with a giant, golden-framed photograph of the Serbian president. [6] The arrests were widely covered in the local and international media and condemned by the umbrella organization of the independent cultural scene of Serbia (NKSS) and international artist organizations.[7] The museum director, for his part, stated to the local press that such forms of artistic intervention “exceed certain limits of civilized norms”.[8] It should be mentioned here that state-ordered repression measures against opponents are not an exception at all, that verbal humiliation and physical violence against journalists or any sort of “whistleblowers” is common, and that there are a number of examples of censorship in Serbia in recent years.

If nothing else these artistic protests, with their broad visibility and the accompanying harsh reactions by the authorities, helped to politicize the art and cultural scene, particularly in Belgrade, where local elections were held in spring 2018. With their horizontal approach and political aim to include citizens in decisions concerning the urban structure and life in the city, the initiative Ne da(vi)mo Beograd (Don’t Drown Belgrade) [9] succeeded in putting forward a list of candidates for city elections in which many people from the cultural field joined. Although not voted into city parliament, the movement gathered a considerable number of votes and represents one of the recently emerging left parties in the region, together with “Zagreb je naš” (Zagreb is ours) from Croatia and “Levica” (Left) from Slovenia.

I will finish this overview with the example of a protest in which the demands of cultural workers and the demands for social housing for evicted families met in the joint struggle for a squatted building. In Belgrade you can find plenty of places that are abandoned by the authorities, left to decay or intentionally ruined, awaiting their privatization as building plots. In one of these buildings (a former army hotel), a group of people organized the social center NNK in April 2018 and after months of fixing and cleaning up the four floor structure they opened it to the public. Five hundred people joined in the first two days of programming in the building, which was big enough to house dozens of initiatives with their social, educational, art and cultural programs, with one floor reserved for evicted families in need of urgent housing. NNK was evicted by the military police soon thereafter, but the activities at the center and the following protests brought together a well articulated group from different fields of struggle: artists, poets, curators and left political groups that emerged from the broader student movement and from the struggle against evictions of debtors and of workers’ families from formerly state or socially owned, and now privatized, housing estates. These days of joint struggle were a test-ground for social movements and artists in learning how to make use of a variety of methods, not only of protesting but also of creating a space to deal with social and political problems in a collective way. In times when the New Right has appropriated the most advanced techniques of media communication, artists, writers, musicians and other cultural workers need to be at the side of emancipatory movements in order to develop a true culture and art of social transformation. The spontaneously held protests of artists and the outcry of cultural workers against commercialization and right-wing culture are not enough. What our situation requires is a practice that leaves the art world as the only point of reference behind and becomes part of the broader struggle in Serbia today.

Rena Rädle is an artist based in Belgrade. In collaborative artistic practice with Vladan Jeremić she explores the relationship between art and politics. She is member of ArtLeaks (https://art-leaks.org) and The Unbribables (https://theunbribables.wordpress.com). Also see: http://raedle-jeremic.net

Notes

[1] Amongst the protesting artists were Danilo Prnjat, Zivko Grozdanic Gera and Uros Jovanovic. Maja Broun, “NE korporativnoj kulturi?,” Vizkultura, (Sep. 19 2016). Accessed at https://vizkultura.hr/ne-korporativnoj-kulturi

[2] For the program see http://www.msuv.org/program/2016-08-01-fack-msuv-eng.php

[3] For the program see http://www.msuv.org/program/2016-07-08-hladni-zid-eng.php

[4] Dejan Sretenovic, “Uvod: Muzej savremene umetnosti u socijalistickoj Jugoslaviji i posle,” Prilozi za istoriju Muzeja savremene umetnosti (Beograd: MSUB, edicija Oko umetnosti #2, 2016), pp.11-14.

[5] The website of the group can be accessed at https://theunbribables.wordpress.com

[6] A few months ago the image of the president became a hot topic when two ministers proposed to place his picture in public institutions and schools. The proposal was welcomed by the Serbian Prime Minister because, as she said, the cult of national symbols of Serbia needs to be strengthened.

[7] The arrests were discussed on e-flux at https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/artists-arrested-during-opening-in-belgrade/7195 and artseverywhere at http://artseverywhere.ca/2017/11/08/unbribables/

[8] “Razlicite ocene u MSUB-u o privođenju umetnika,” Seecult, (Oct. 27 2017). Accessed at http://www.seecult.org/vest/razlicite-ocene-u-msub-u-o-privodenju-umetnika

[9] The initiative has its roots in the occupation and maintenance of empty private or public buildings and eventually widened its political focus, joining protests and blockades against the privatization of city space and communal services, and illegal evictions by a cruel system of banks, courts and private bailiffs. The movement grew considerably during the protests against the Belgrade Waterfront redevelopment, sparked by the illegal demolition of buildings at Savamala district by mysterious masked people in 2016. See also: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/may/26/serbs-rally-against-shady-demolitions-after-masked-crew-tied-up-witnesses