Update from the City of Brotherly Love

Nato Thompson

To state the obvious, the Trump presidency has provided a steaming pile of abject news as our daily breakfast. It’s exhausting to wake up each morning and find yet another disaster awaiting you. If anything, I would say all of us might fight, tooth and nail, the overwhelming need to go numb. How much crap can we take?

Certainly, the pushback to Trump was the Women’s March but that protest seemed to quickly fade and not be followed up by anything of nearly as much significance. Sure the pink pussy hats permeate protest but in general, the roar of mass resistance has subsided. The period is now punctuated either by issue-specific protest and skirmishes, or an exciting (but perhaps not as newsworthy) set of long-term projects that have been dealing with structural issues that one might describe as community based or socially engaged art.

I am writing from the incredible, affordable and mixed race land of Philadelphia. For those that do not know, it is a city one and half hours to the south of New York City and the same distance to Baltimore and DC to the south. It is a city of 1.5 million that, like many cities, is facing a moment of gentrification. It is a city that is 44% African diaspora and thus has faced the racist housing programs that have shaped America’s cities. That said, with that, it has a complex cultural space with a rich history. This city is also affordable and is one of neighborhoods. People still squat here (something practically going extinct in the United States) and collectivist housing still exists. In my opinion, in a country where rising career ambitions and housing prices seem to define the arts and cities, Philadelphia is an impressive contrast.

I want to highlight some interesting trends and projects that are demonstrating a certain political attunement. There is so much great work happening in Philadelphia that I am excited to share this with the readership. I also would like to use this opportunity to wonder aloud (in perhaps what could be construed as an unnecessarily provocative fashion) why it is that there is less conceptual activist art under Republican presidents?

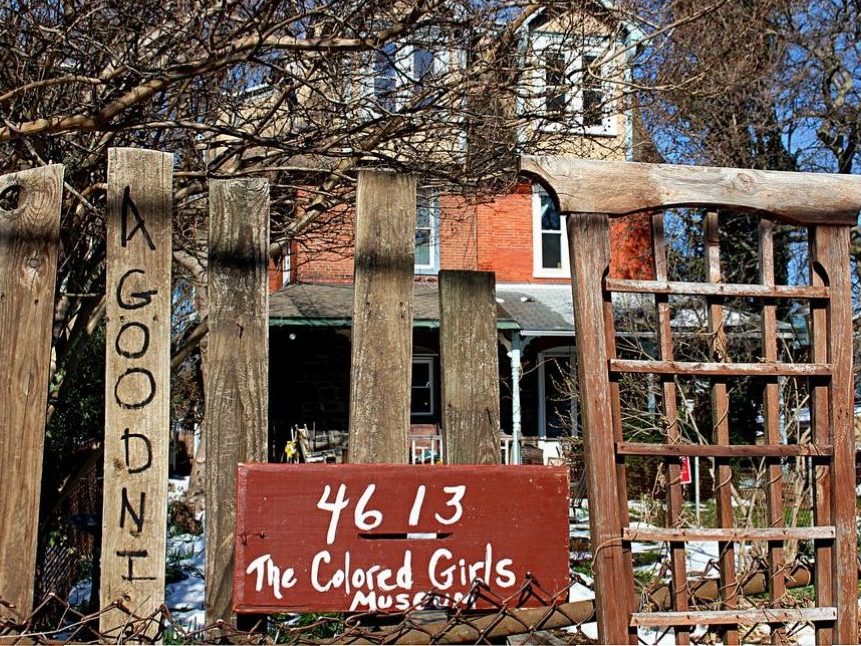

So first, let’s start with the good news. The good news is that there is a lot of interesting political art in Philadelphia. Let’s begin with a house museum in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia that calls itself, The Colored Girls Museum. Started in 2015 as an initial pop-up project for the Fringe Arts Festival by Vashti Dubois (in her home), this unique house museum has a particularly insightful mission. As the website states, “The Colored Girls Museum distinguishes herself by exclusively collecting, preserving, honoring, and decoding artifacts pertaining to the experience and herstory of colored girls.” Vashti Dubois, founder of this fairly recent project, considers the role of curating one of caring and curing. And the subject of that caring and curing being the mythical and actual subject of the colored girl.

With this particular mission, this institution places the role of art into relationship with a specific historic subject. The space itself has a relatively ambitious program schedule and Dubois works with Michael Clemmons and Ian Friday to set forth a rigorous curatorial project. Because the museum is situated in the space of the home, the work itself immediately evokes an intimacy and domesticity that obviously presents not only a different feel from a museum or gallery, but more so, a situated politics.

Another Philadelphia based project of note has been instigated by the Village of Arts and Humanities (an organization dedicated to social justice facilitated between the arts and community) titled the People’s Paper Co-op. Beside the work of the organization itself which is inspiring (and not easy), the People’s Paper Co-op takes on a variety of projects that connects incarcerated individuals with artists. One of these initiatives they titled “People’s Expungement Clinics” which works to clean up or clear up the criminal records of participants. As part of this process, individuals print out their records, pulp them and create recycled new paper. A new material is born out of both a process and an existing material.

Both of these projects are longer-term efforts aimed at dealing with the outrageous history of racism, patriarchy, and capitalism as well. The ongoing assault of an increasingly privatized and racially organized urban environment has provided much grist for the mill of socially engaged art. And that work is certainly happening and has been happening.

That said, the Trump administration has provided a stark rattling of current political sensibilities. Not at all unlike the early years of the Bush administration in the post-911 reality, the current period is marked by a sense of political vertigo. The scale of the assault on common sense is so vast that much activism, at times, can either be forced into a reactive state, a keep your head down and stay working on long term problems state, or even, stasis.

While the rest of Pennsylvania went Red during the elections, last November, Philadelphia elected what has been described as a Black Lives Matter candidate, Larry Krasner as District Attorney. Extremely critical of the police state, the city’s chief law enforcer has pushed forward a series of criminal justice reforms unheard of across the country including a declaration that “These policies are an effort to end mass incarcerations and bring balance back to sentencing.” In his first three months in office, he fired 31 prosecutors he felt were not committed to equity, he let go 29 officers who were deemed tainted in terms of their commitment to the neighborhoods, and he has actively decreased the length of parole sentences. In other activist politics, there have been numerous protests at ICE headquarters, with anarchist art space Spiral Q producing banners and puppets. As well, there exists an ongoing Occupy-esque encampment currently outside city hall with kitchens, library and tents.

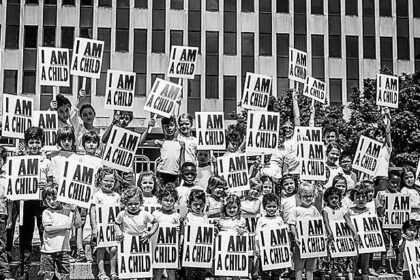

As often is the historical case, the work of pushing back on a fascist administration goes to the more didactic, propagandist artists. Protest art, in its more straightforward sense, is flourishing. But more conceptual work has a difficult time getting its engine going as the pushback to the Trump administration seems to have been taken up by MSNBC, CNN and the New York Times. Taking meme-like potshots at Trump appears to be the fuel for the contemporary news media. And I suspect, this sort of inertia of tabloid-esque pushback sucks some energy out of those looking for a nuanced form or critique. For those pre-disposed toward a unique position in the face of total assault, the options are limited.

Perhaps it is an interest in being interesting (that particular disposition that Neitszche found problematic) that makes more conceptual art allergic to wide-spread political disdain. Perhaps it’s the fact that we wake up to Trump that we don’t particularly feel like making art about it. Whatever the case, the same phenomena took place during the early Bush years. Yes there were mass protests but I would say that much more artwork work went into anti-gentrifcation, anti-patriarchal and issue-based concerns. The other read on this would be to say that structurally, as much as Trump is a nightmare, many are also aware of deep neoliberal problems that have persisted for decades.

Thus, I would say that for this report from the field of Philadelphia, the work of didactic protest and long term socially engaged art are doing great. There is enthusiasm and even electorally, a progressive agenda is very much on foot at the polling station. For those invested in more subtle forms of political opposition, the prevailing winds of anti-Trump media and protest nearly eviscerates anything interesting about protest. Meme culture almost makes protest boring. On the flip side, of course, perhaps artists should revel in the boring sometimes.

Nato Thompson is a curator and author and works as Artistic Director at Philadelphia Contemporary. Philadelphia Contemporary is a mobile contemporary art organization in the process of creating a civically-engaged non-collecting museum in the city of Philadelphia. Previous to Philadelphia Contemporary, he worked at the New York-based public art organization Creative Time as Artistic Director which he joined in January 2007. Since then, Thompson has organized such major Creative Time projects as The Creative Time Summit (2009–2015), Pedro Reyes’ Doomocracy (2016), Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014), Living as Form (2011), Trevor Paglen’s The Last Pictures (2012), Paul Ramírez Jonas’s Key to the City (2010), Jeremy Deller’s It is What it is (2009, with New Museum curators Laura Hoptman and Amy Mackie), Democracy in America: The National Campaign (2008), and Paul Chan’s Waiting for Godot in New Orleans (2007), among others. He has written two books of cultural criticism, Seeing Power: Art and Activism in the 21st Century (2015) and Culture as Weapon: The Art of Influence in Everyday Life published in January 2017.