Uncertain Realities: Art, Anthropology, and Activism

Christopher Wright

Art, anthropology, and activism are three academic disciplines, but also types of action, forms of cultural production in themselves, that were brought into close proximity in the context of documenta 14, a large-scale art event that took place in Kassel, Germany and Athens, Greece in 2016-2017. Proximity is a useful term as the extent to which these three activities merge or fold into each other – or not – is the key issue at stake here. Documenta 14 had the stated aim of “Learning from Athens” and wanted to be a “platform” for change.[1] It defined itself as a “theatre of actions” that aimed to “produce situations, not just artefacts to be looked at,” so “exhibition” is not always a productive way of describing it.[2] The written materials produced by documenta – online, in print – refer to this learning as a process of “aneducation.”[3] This seeks to develop “relationships with learning institutions, artist-run spaces, and neighbourhoods to investigate the correlation between art, education and the aesthetics of human togetherness,” and is “less an attempt at a curriculum than a cacophony, a chorus of voices that not only speaks but listens, shifts, doubts and dreams. It is a mode for unlearning, or, conversely, a nourishing act, a warm gesture that reaches out to the possibility of learning otherwise.”[4] There is a focus on “un-learning” and a particular kind of uncertainty, both in terms of the uncertainties thrown up by the current events in Greece and in retaining a sense of the open-endedness or uncertainties of artistic endeavours. This insistence on uncertainty has a strong bearing on many artists’ views about any kind of responsibility they may or may not have in a given context. It also seems in many ways to be a project that has much in common with anthropological concerns, especially the “aesthetics of human togetherness.” And all of this took place in the context of the Greek crisis, the historical relations between Greece and Germany, between “north” and “south,” and coincided with a European refugee crisis. Many of the artworks in documenta 14 sought to comment on, or actively intervene in, these crises.

Art, anthropology, and activism all deal with notions of uncertain realities: they question what constitutes reality, use reality as a material, and attempt to affect reality and change it. In terms of documenta 14, this questioning of reality takes place in the context of the economic, political, social, and emotional uncertainty that is a central element of the Greek crisis itself. But is this ongoing crisis something that requires the intervention of contemporary art? How can works produced under the banner of these fields actually intervene in the everyday experience of crisis? How do documenta 14’s ideas about “un-learning” relate to those kinds of uncertainty? There is a concern with uncertain realities in two senses –reality as something that is the common material of all three fields, something they all deal with, but also the sense of an uncertain reality that is part of the experience of crisis. What is at stake when you bring these three fields into contact with each other is partly to do with what tools and methods each employs to investigate or approach reality and subsequently to intervene in that reality. But also at stake is how those methods are thought to impact the reality they investigate. We are perhaps used to thinking about art as something open-ended, uncertain, but uncertainty is something that anthropology often finds more problematic in terms of the outcomes produced. There is perhaps a reluctance on both sides here: contemporary art wants to retain an uncertainty, an unlearning, even an unrealism; anthropology is not so keen. Of course, these are sliding scales, and we are often dealing with assumptions, traditions, and not always explicitly announced positions, but these ideas of uncertainty do have important implications for any ideas of responsibility in the kinds of social contexts both art and anthropology deal with.

Underlying many of the aims of documenta 14 is a particular constellation of art, anthropology, and activism in which anthropology is seen, from the perspective of some sections of contemporary art, as a means of theorizing the social and as a method for accessing it. Activism is an important third term here, as a significant sub-field of contemporary art is overtly concerned with actively intervening in the social. Art practices intervene in ways that are sometimes hard to distinguish from what would normally be labelled as activism. One example is the amazing work of artist Theaster Gates who runs a variety of social projects in South Side Chicago. Gates uses money from the sale of his artworks in galleries to fund training courses for unemployed Chicago youth. In doing so, he co-opts the wealthy patrons who buy the work into supporting a local social regeneration scheme.[5] The notion of “the work” becomes stretched and altered here; so too does the notion of the artist as the singular creative producer of art objects. There are artworks in galleries, but they are only one element of the wider “work,” effectively blurring boundaries between art and activism. The artist and his individual creativity in making artworks likewise becomes one element of a more diffused creativity. Are the roofs made by Chicago youth as part of the training schemes organised by Gates to be considered as part of the artwork? A consideration of the relationships between art, anthropology, and activism reveals what is at stake in assertions, explicit or implicit, that art can change social life. Gates’ practice is one example of what art can actually do to address crisis

It is currently a commonplace assumption that contemporary art has contributed to processes of “urban regeneration” (including gentrification), created forms of ongoing sociality, and influenced political change. The “social turn” of contemporary art is not just concerned with an interest in drawing from social reality or using it as a kind of raw material in artworks; it presumes that art can intervene directly in the social and alter it positively. But where are the lines that distinguish anthropology, art, and activism from one another? Does it matter that the borders might be blurred? That an art event as large as documenta 14 could see itself as centrally concerned with social change, the politics of crisis, and the north/south divide suggests that there is a massive investment in art as a force for change. Perhaps this is a kind of civil contract of contemporary art?

Some of this, of course, has its roots in much earlier concerns in art. Clearly, one important antecedent is Joseph Beuys’ idea of “social sculpture,” especially when one considers that artist’s massive influence on documenta as an institution. It is worth revisiting his definition:

My objects are to be seen as stimulants for the transformation of the idea of sculpture […] or of art in general. They should provoke thoughts about what sculpture can be and how the concept of sculpting can be extended to the invisible materials used by everyone.

THINKING FORMS – how we mould our thoughts or

SPOKEN FORMS – how we shape our thoughts into words or

SOCIAL SCULPTURE – how we mould and shape the world in which we live:

Sculpture as an evolutionary process; everyone an artist.[6]

Beuys, and his artwork, featured directly in documenta 14 when the Kosovan artist Sokol Beqiri took a cutting from one of Beuys’ 7000 Oak Trees (Kassel, 1982) and grafted it onto a tree outside the documenta 14 offices in the compound of the Athens Polytechnion for his work Adonis. At the time I last saw the tree, it looked – tellingly, perhaps – as if the graft had not taken. But the historical resonance of this concern with the social formed a context for many of the artworks exhibited or enacted in both Athens and Kassel. These included Rick Lowe’s project, which involved renovating an old commercial premises in the Victoria Square area of Athens and turning it into a community center running a range of art-based workshops, printing a local newspaper, and organising events, all with a particular focus on working closely with local residents and with the migrant and refugee population with which the area was then very much associated. The Facebook page for the project, one of its public interfaces, refers to the “work” as “social sculpture.”[7] The Victoria Square project is a long term one; it began in 2016 and is currently still running, although it remains to be seen for how long. Questions about what kind of timescale validates, or invalidates, a project like this have a direct bearing on anthropological concerns as well as those of artists. Lowe has run an incredible project along similar lines in Houston, Texas – his hometown – for many years.[8]

When I visited the work in the autumn of 2017, there was a small group of young people. The women were wearing hijab and sitting together in a group slightly separate from the men. They had all been working on a visual project of some kind – scissors, paper, notes, and various images lay around – and were taking a break to eat, speaking quietly among themselves in their gender-defined groups, while sitting at a large table that was prominently situated in front of the large shop window of the space. The street was quiet at that time in the morning, and there was no apparent audience for the group’s work, inside or outside the space, other than myself. The project support staff were happy to show me around, only interacting with the young people when asked to do so. My initial question was the extent to which the young people saw themselves as participants in Lowe’s artwork? The experience also made me think about what counted as “the work.” Should I be watching the group of young people working? Looking at what they made? Or somehow “watching” the whole social context? Was this a gallery? What are the limits to the work? Whose is the artistic labour? Like Beuys’ definition, the work provoked me to think about what art is and can be. But how does that sit with the reality that the project intervenes in the lives of people? Lowe’s project is not concerned with an academic discussion of the limits of art, but with a kind of situational responsibility. The work undertaken by the Victoria Square project ranges from putting new migrants in touch with relevant local NGOs and helping them with bureaucratic paperwork to organising African drumming classes open to the public. From previous conversations with staff, and unfortunately only briefly with Lowe, I had a sense that those involved clearly thought the project could have a really positive impact on people’s lives and on the area and community more widely. There was a strong feeling of individual and group responsibility towards the situation.

Projects like Victoria Square demonstrate that there is a real attempt among a major strand of contemporary art to intervene in the social in ways that draw, explicitly or not, on both activism and anthropology.

Various kinds of uncertainties are thrown up in crisis. Eleana Yalouri has talked recently of older Greek notions of prophecy, about how one may as well consult an oracle as an economist in order to understand the current crisis in that country.[9] What effects and/or affects do the works produced under the banner of art, anthropology, and activism have? Here we come to one of the key issues in bringing them together: the boundaries of the works that are produced. What is the “work” that is produced by Rick Lowe in Athens? Is it necessary to produce a “work”? Documenta expressed a concern with “events,” not just with objects for exhibition. Given a certain reframing, is there a way in which we can think of anthropologists doing fieldwork as a “work”? There is much at stake here: not only the massive financial project of documenta 14 and its cultural impact, but also the massive investment in art’s agency on a wider social scale, the hope that art can change social reality in a positive way.

If we are thinking about art, anthropology, and activism in relation to times of crisis, if they are to be charged with the task of tackling crisis, then we also need to acknowledge the various responsibilities involved. Anyone working in these kinds of contexts has what can be called a “situational responsibility,” a position in relation to the social, political, and economic particularities of a specific context. It also means an attention to the creative, imaginative, and affective particularities of that context. This situational responsibility entails firstly a recognition of that position (in this case, documenta in Athens). But what follows from that self-reflexivity – including an interrogation of the term “responsibility” with all of its ideological overtones – is an attention to the ethics of engagement and intervention. These ethics are not predetermined – by the artists, the anthropologist, or the activist – but are specific to a particular context. They are also emergent; they arise through a process of collaboration and engagement. These ethics are open and adaptive.

There is sometimes a misperception from the perspective of contemporary art that anthropologists are almost incapable of action because they are bound by a set of strict ethical guidelines, a disciplinary imposition that can be seen as a burden by artists. This is both true and not true: anthropologists in the UK do have an ethical code of conduct set out by the Association of Social Anthropologists.[10] But the reality of fieldwork means that ethics are actually about an ongoing and constantly shifting process of negotiation. And who is to say that the ASA’s ethics are the relevant ones? What of other culturally specific ethical codes that may be as, or more, relevant in certain cross-cultural contexts and encounters? Of course, the reverse is also true: anthropologists have the misperception that artists are not bound by any ethical responsibilities. The work of Gates and Lowe are both guided by a strong sense of ethics. The position and possibilities of being an actor or activist in any given situation entails a responsibility to that context. Some artists might argue the opposite, for the need to be irresponsible, to act outside of ethical codes. I am not suggesting here that there is one binding set of agreed-upon ethics, or corresponding form of responsibility, but that acting in the world necessarily entails a network of entanglements with other actors, and that contemporary art’s – and artists’ – claims to intervene positively and productively in crisis comes with forms of situational responsibility.

Many contemporary artists and activists aim to catalyse new forms of solidarity, to promote new knowledge and understanding in their audiences, and to intervene in civil society in a positive way. But anthropologists may be reluctant participants here – there are arguments for and against calls for a more “activist anthropology.” Joseph Kosuth’s 1975 argument that the artist is perceived as someone engaged in his or her own culture while the anthropologist studies someone else’s culture is relevant to understanding work like the Victoria Square project.[11] Perhaps many of the artists involved in documenta 14 are like anthropologists – they study other people’s culture – but also like activists – they intervene in it.

Bringing anthropology, art, and activism together may entail a reconfiguration of the creative process. Where does creativity lie in the kinds of social intervention and activism that some artists are pursuing in and as their work? With the artist? With their participants/collaborators? With the culture? With the particular situation or context? Perhaps what is necessary is an opening out to different processes of creation, or the development of what the anthropologist Steve Feld calls a “co-aesthetic.”[12] What if, rather than coming to a situation with a pre-formed aesthetic, as an artist may, one treats aesthetics as something that emerges from a learning process, something more anthropological, the product of a particular kind of encounter? For artists, this would mean relinquishing a sense of their own creative priority or importance, or at least an opening out of that creativity into a wider and more inclusive field. This is one area where artists can learn a great deal from anthropologists and activists who are used to constantly adjusting what they do in terms of their research to what is directly relevant to a particular group and situation. Perhaps grafting is a useful analogy? Grant Kester makes a really strong and convincing argument along similar lines around the artist Francis Alÿs. Despite recruiting a large number of students to vainly try shifting a huge sand dune with shovels in his 2005 artwork When Faith Moves Mountains, Alÿs is the sole individual “able to accrue the symbolic capital necessary to enhance his career as an artist” (emphasis added).[13] Does the labor of the participants in the Victoria Square project enhance the artistic capital of Rick Lowe? Does that matter if the end results for the participants are positive?

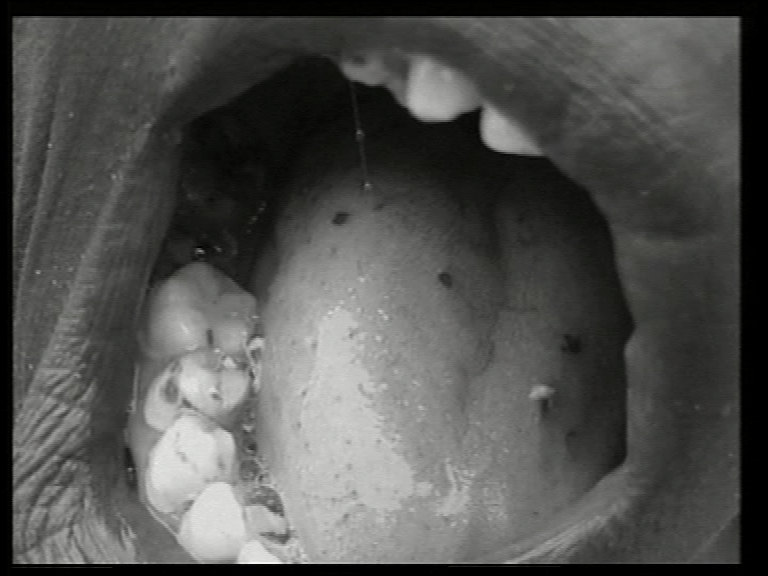

I want to think further about the relationship between art, anthropology, and activism by considering a digital video work, De la vie des enfants au XXI° siècle. The film was created by a former Senegalese street child, Papisthione, with the help of another ex-street child, Grand Malien. The entire film can be accessed online.[14] It is an incredibly powerful piece of visceral filmmaking, often very harrowing, that records in a series of episodes the daily experiences of children living rough on the streets of Dakar in Senegal in grainy, pixelated black and white. There is no voice-over narrative to guide us, and the protagonists speak only intermittently. An early section of the work consists of an agonisingly slow pan along the bodies and bare feet of children sleeping huddled together on the floor of a shop doorway – with callouses, sores, rubbish, and dirt in plain view – until the camera, and our gaze, ends up focusing on one particular child who, prone, at first appears dead. One feels a palpable moment of relief when the child’s chest finally moves.

The film was shot on a small consumer-level digital video camera by Papisthione between July 1999 and January 2000. Papisthione and Grand Malien had received basic audio-visual training while at the Man-Keneen-Ki residential school and orphanage in Dakar, which was set up with the help of French artist/activist/stage producer Jean Michel Bruyère in 1996 as an association of various NGOs concerned with improving the lives of street children through art and activism. Bruyère helped to finance the school, which he also ran, until it closed in 2006. The film was a project intended to publicize the school’s work, initially just locally, and as a way of practically advancing the development and employment chances of individual children through audio-visual training. Papisthione’s interest in pursuing visual skills was motivated by the earlier success of another child at the school, Sada Tangara, whose photographic project depicting street children, The Big Sleep, did well in publicizing the work of the school on an international scale.[15] Papisthione’s film was produced in collaboration with the French organisation LFKs, an arts collective, of which Bruyère is a key member, based in southern France. LFKs is concerned with the creation of art, with research, and with direct social action in liaison with local agencies.[16]

Papisthione was 17 years old at the time he shot the film, and Bruyère describes the process as one in which he provided a video camera and tapes every day over a long period. Grand Malien was a tall, strong ex-street child who could provide protection for Papisthione during the filming process, and the film’s credits refer to him as an assistant. Their project was to “document the world they came from.” [17] Bruyère describes the resulting footage as “odd and harsh, some almost unbearable.” The daily footage was screened to staff and children at Man-Keneen-Ki until everyone felt they had enough to show the lives they knew so well. The video technology of the time did not make the editing process very easy, or portable, and Bruyère worked on editing the footage in a professional video studio. Papisthione was present at some of these editing sessions, having been invited to screen the film at a festival in Belgium that included the anthropological filmmaker Jean Rouch, whom he met. Bruyère and LFKs had previously brought street children resident at the Man-Keneen–Ki school to Europe to appear in stage performances, and almost all of the school’s boarders travelled there at least once to participate in shows created for them. They performed for the first time in Paris in 1997, in a show called Poèmes à l’infect at La Grande Halle de la Villette, but also at big festivals (including three times at the Festival d’Avignon), national theatres, opera houses, and galleries in France, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Bruyère says he worked closely with two famous Senegalese artists and friends, Goo Bâ and Issa Samb-Jo Ouakam, on editing Papisthione and Grand Malien’s footage. He also worked “in constant relation with the work of the philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne who was at that time the cultural adviser for the President of the Senegalese Republic.” Bruyère and his collaborators worked intensively on the editing, altering the color (switching the footage to black and white), the speed, the sharpness, and even re-recording some scenes in reverse. Bruyère says this was to give the footage “a clear distance from reality,” not because the events depicted were untrue, but because he wanted to establish the film as a kind of “poem” since Papisthione and Grand Malien were not trained documentary filmmakers and were “unaware of documentary filmmaking rules and ethics.” The film is accompanied in places by a minimalist soundtrack. For me this is a disturbing element, adding an aesthetic dimension, a distance, that I struggle with.

In terms of Papisthione’s involvement in the post-production, Bruyère says,

I was constantly talking to him, showing and explaining as much as I could about how and why things were done. He was a student of the art school for street kids that I built and I was aware that giving him as much education as possible could make the difference between staying alive, or returning to those terrible conditions. We were all aware of how important it was not to fail in terms of teaching, to not miss a single occasion to give them effective tools, to give them weapons with which to struggle against their unfair fate. So I showed him everything I could. I am sure he knew enough after the editing process to be able to explain to others what had been done and why, and this is a very important point.

Despite the creative impact of the post-production work, for Bruyère the film belongs to Papisthione and Grand Malien because it is their footage, because it is so close to their lives: “it was his own life, and that of his friends, his way of being and making a living just two years before he first got access to a video camera.”

Bruyère discusses the dynamics of the editing process:

You have to remember that this was twenty years ago in the context of the Senegalese education system and you have to try and imagine what that relationship between a student and a teacher, an adult and a child, would have been like. We were responsible for 43 street-kids who were used to surviving mostly through criminal activity. There was a certain authority, that was the only way to keep the whole thing going. I asked [Papisthione’s] point of view about what I was doing in editing, but his responses were based on an alternative knowledge.

To an anthropologist the relationship between that alternative knowledge and “documentary filmmaking rules and ethics” is key.

The intention of Bruyère and Man-Keneen-Ki

[…] was to use the film in our collective art-action to protest about and change the situation of homeless children in Dakar. The film was primarily made for this purpose–to be one element in a larger exhibition about street children called Enfants du Nuit. But, after a while, we could also see that it had its own potential and that the use of this potential by Papisthione as an independent filmmaker could offer him a solution for his personal future.

Papisthione remained in France for some time after the editing process as the completed film was subsequently screened at various European film festivals. The French television company Arte, among others, bought the screening rights to the film. Bruyère says he had nothing to do with the deal, and the film was subsequently screened by Arte despite his opinion that

This film 1. was not something we could sell, 2. was not designed to win distinctions in festivals and other kinds of arty big circus events. But I thought about it differently when it came to Papisthione’s interests. I was the person picking him up out of the hell of the streets and giving shelter and schooling: to be frank, I just could not refuse an opportunity for him to have fun traveling everywhere, to have dinner with glorious old guys like Jean Rouch, to make some money and to have worldwide fame for a while. This was an unexpected but good outcome for him and Grand Malien.

Bruyère goes on to say that “it went so well for Papisthione … that he never showed up again, we did not hear that much from him anymore, and we felt fine with that too: what is good for them as an opportunity and/or good for them as individuals is good for us anyway.” Bruyère does not know what eventually became of Papisthione. Among those who met Papisthione, there is some disagreement about who benefitted from the Arte deal, and suggestions that he deliberately overstayed his visa to try and avoid returning to Senegal.

Papisthione and Grand Malien’s film raises emotive and difficult questions about the relationship between art, anthropology, and activism. The long slow pan along the children’s feet feels unbearable to me because I am witness to awful conditions without any direct ability to influence them. This is a common enough experience in watching documentary and a product of my own position as an affluent, middle-class, white viewer. But this film has little of the contextualization, explication, or narrative voiceover of much documentary practice. These absences make it more disturbing as a viewing experience. Although the truth of the events depicted is not at stake, I am not convinced I am watching documentary; but the idea that this might be art is too much to bear. If it is framed as documentary, I am somehow reassured of its ethics. Of course, this reassurance is misplaced, but if it is art, how am I to think of its ethics? I am also concerned about the role of the cameraperson. Who is showing me this hell? When I first encountered the film, I had no idea that those holding the camera were Papisthione and Grand Malien. My initial response was to be shocked, not just by the footage itself and the events depicted, but by the fact that a cameraperson had done these things with a video camera in this context. At one point in the film the camera nearly enters the mouth of one of the street children, showing us bad teeth and saliva in extreme close-up. It is an amazing piece of cinema, as well as a terrifying existential moment. It feels as if I, the viewer, were about to be ingested.[18] I am more at ease with the film when I know that the cameraperson is an ex-street child, but I am also deeply suspicious of that ease. Why does the knowledge that Papisthione was holding the camera make me less uncomfortable? It is almost as if, being one of them, Papisthione partially elides my discomfort at watching these events by taking away – even if only momentarily – the guilt of my own position. If I thought it were Bruyère holding the camera, it would be worse. Of course, what is assumed, and elided, in my response to the authorship is precisely the point.

A significant part of my discomfort in viewing the film also has to do with my inability to place it in terms of any clear fit within art, anthropology, or activism. It exceeds any clear disciplinary framing. But this is a productive ambiguity. The film blurs the boundaries between all three. It is beautiful, terrible, awfully visceral, and incredibly creative in terms of how the camera is used as a tool to enter the lives of these street children. I certainly feel that I have an incredible amount of ethnographic understanding of a particularly affective kind through watching the film, and it is a potentially powerful tool for activism. But how am I supposed to appreciate it aesthetically? How can I possibly do that at all given its subject matter? This is of course a long-standing issue in documentary filmmaking, beginning perhaps with Joris Ivens and Henri Storck’s 1934 film depicting the awful living conditions of unemployed Belgian miners, Misère au Borinage, in which there is a deliberate attempt to suppress any aesthetic beauty. But, as Bruyère points out, Papisthione and Grand Malien are not trained documentary filmmakers with an established sense of documentary ethics from a “Western” perspective and tradition. This film is concerned with other aesthetics, even with the editing input from Bruyère, and perhaps also with a different ethics. Watching the film certainly sets my own ethics – their limits and their positionality – in stark relief. Maybe what makes Papisthione’s film so powerful is precisely the fact that he has not learnt the “rules” of documentary filmmaking? As a visual anthropologist, I am excited by the prospect that the film was edited in relation to Senegalese philosophical concerns, not “documentary rules and ethics.” Bruyère himself is keen to establish the film as a “poem,” not a documentary. But “poem” is often a residual category that we use for films that do not fit easily within other genres. In that sense it is a similar designation to the way in which “poetic” is sometimes used, applied to something that cannot otherwise be adequately described. It is concerned with a certain kind of license too, a point that must be seen in relation to the notion of a situational responsibility. The film is productive in its disruption of the usual accepted boundaries between art, anthropology, and activism, and I think the lack of a suitable term for it is a positive. Perhaps there is a Senegalese term that is more appropriate? The film holds out the possibility of an other aesthetics.

The film makes me productively question the notion of an “artwork” in the context of bringing together art, anthropology, and activism. Are the activities of Man-Keneen-Ki and LFKs/Bruyère taken as a whole “the work”? Or just the film and my viewing of it? What is entailed by thinking of the activities of something like the Victoria Square Project taken as a whole as “the work”? Should we think of Rick Lowe as “the artist” in that project? The film is certainly an example of a co-aesthetic: Papisthione’s footage, Bruyère’s and others’ editing. It is also something that provokes me to think again about any easy distinctions between anthropology, art, and activism. Those distinctions are less important than actively and productively working with some of the methods and impacts they share in common to intervene positively in various crises with a notion of situational responsibility. That is, of course, more important than any territorial manoeuvring. But if we are considering the relations between art, anthropology, and activism, particularly in terms of research, then the distinctions, or lack of them, between all three are revealing.

“Social sculpture” projects like Victoria Square can productively draw on anthropological methods and concepts, as well as those of activism, in their planning and development as they unfold and mould themselves to specific contexts. Projects like this aim to work in some kind of extended way with local people, “the work” involving social interactions that develop, change, and are in some sense uncertain. But that uncertainty needs to be seen in relation to a situational responsibility. The residues that are accumulated from these interactions subsequently form “the work” in a different way, as something that can be exhibited, posted online, etc. But the residues that are more important are the effects on participants’ lives, something that Lowe acknowledges. Many of these issues around distinctions between art, anthropology, and activism are products of habit; it has required a conscious decision to try to describe the Victoria Square project as a “project” rather than a “work” by Lowe. These are the habits and the art-world systems that need to be challenged. Bruyère suggests, art, anthropology, and activism are not only linked but “are one single thing.” “I do not see myself as an artist,” he goes on to say, “or an activist. I simply believe in creativity and friendship.”

The Papisthione film and the Victoria Square project also suggest that in some contexts artists need to take the co-aesthetic seriously and expand the notion of artistic authorship, creativity, and cultural capital into something more inclusive. What kinds of cultural capital have Papisthione and Grand Malien accumulated from the film? The amount of faith poured into the belief that contemporary art can positively intervene in the realities of people’s lives suggests that “social sculpture”deserves to be assessed in the light of continued detailed research between art and anthropology.

Christopher Wright is Lecturer in Anthropology at Goldsmiths, University of London. From 1992 until 2000, he was Photographic Officer at the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. He is a coeditor of the books Between Art and Anthropology and Contemporary Art and Anthropology.

Notes:

[1] “Documenta 14,” Documenta 14, http://www.documenta14.de/en/ (accessed January, 8, 2018).

[2] Quinn Latimer, Adam Szymczyk, “Editors’ Letter,” South Magazine Issue #6 [Documenta 14 #1] (Fall/Winter 20156), http://www.documenta14.de/en/south/12_editors_letter (accessed December, 17, 2017).

[3] “Public Education,” documenta 14, http://www.documenta14.de/en/public-education/ (accessed December, 17, 2017).

[4] ibid.

[5] See, for example, Carol Becker et al., Theaster Gates, (London, New York: Phaidon Press, 2015). Interestingly Bruyère has previously collaborated with Gates.

[6] Beuys’ quote from Theory of Social Sculpture, 1979, as cited in: Chris Thompson, Felt: Fluxus, Joseph Beuys, and the Dalai Lama (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 88-89.

[7] “Victoria Square Project – Home,” Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/VictoriaSquareProject/ (accessed January, 22, 2018).

[8] “Project Row Houses,” Project Row Houses, https://projectrowhouses.org/ (accessed January 23, 2018).

[9] Eleana Yalouri, “‘The Metaphysics of the Greek Crisis:’ Visual Art and Anthropology at the Crossroads,” Visual Anthropology Review 32, no. 1 (2016): 38–46.

[10] “Ethical Guidelines for Good Research Practice,” Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth, https://www.theasa.org/ethics/guidelines.shtml (accessed January 23, 2018).

[11] Joseph Kosuth, “The Artist as Anthropologist,” in Art After Philosophy and After: Collected Writings, 1966-1990, ed. Joseph Kosuth and Gabriele Guercio, (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1993 [1975]), 107-128.

[12] Steve Feld, “Dialogic Editing: Interpreting How Kaluli Read ‘Sound and Sentiment,’” Cultural Anthropology 2, no. 2 (1987): 190-210.

[13] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2011), 73.

[14] The whole film can be found online here: Papisthione and Grand Malien, “De la Vie des enfants au XXI° siècle,” filmed 2000 at Dakar. Video, 57:21,

http://www.lfks.net/en/content/de-la-vie-des-enfants-au-xxi°-siècle (accessed January 1, 2018).

[15] See Jean Michel Bruyère (ed.), L’Envers du Jour: modes réels et imaginaires des enfants errants de Dakar (Paris, Madrid: Editions Léo Scheer, 2001). The Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne also contributed to the book.

[16] “LFK(s) collectif,” LFK(s) collectif, http://www.lfks.net/en (accessed January 05, 2018).

[17] Jean Michel Bruyère, from email correspondence in the early months of 2018. All further quotes from Bruyère are taken from this personal correspondence and I am extremely grateful to him for his time and his honesty.

[18] There is an anthropophagic element to this that could usefully be explored further.