Between Uneven Hermeneutics and Alterity: The Dialogical Principle in the Art – Anthropology Encounter

Arnd Schneider

This essay starts with a rhetorical figure, ‘speaking terms,’ which I take from James Clifford’s seminal essay On Ethnographic Surrealism.[1] There he writes about the fertile encounters between artists and anthropologists in 1920s and 30s Paris, especially around the journal Documents and specifically comments on the collaboration between George Bataille (an editor of Documents) and the anthropologist Alfred Métreaux, and concluded that “French ethnography [was] on speaking terms with the avant-garde.” [2]

As much as one can project a romantic view onto another historical period, the idea here, obviously, is not to revive the surrealist encounter with ethnography in the present (although much might be learned from some of the strategies and devices then employed).[3] Rather, the intention is to abstract from a historically contingent case and reflect on the ‘speaking terms’ themselves, and how they might be useful in contemporary times. This is to say, how ‘speaking terms’ could be established as philosophical first principles which could become valid anywhere, anytime, that is in a ‘contemporary,’ as a “…fictive relational unity of the present ,” or “disjunctive unity of present times ,” in the words of philosopher Peter Osborne, when he writes about the ‘contemporary’ in relation to ‘art.’[4] Thus, ‘speaking terms’ can neither mean to have preconditioned meaning, nor do they imply a simple leveling position of speaking subjects, in fact they precisely allow for difference between them.

***

In anthropology, during the last decade or a little longer, a substantial theoretical debate has revolved around the issue of radical difference or alterity, and what are held to be basically incommensurable world-views (such as those of certain Amerindian societies and the West). In the introduction to my recently edited Alternative Art and Anthropology, I have shown how artist-photographer Diego Petrella, engages with others in subtle ways (specifically through his work with certain Amerindian groups in Brazil) without infringing their semantic territory.[5] In a different mode, artists Julia Rometti and Victor Costales also problematize alterity in their work El Perspectivista (2013) through the construction of a fictitious encounter of an exiled anarchist with an Amerindian community. Both Petrella and Rometti and Costales push up against the borders of alterity, the incommensurable, and that which cannot be translated further.[6] At the same time, they leave open an indeterminate space for translation.

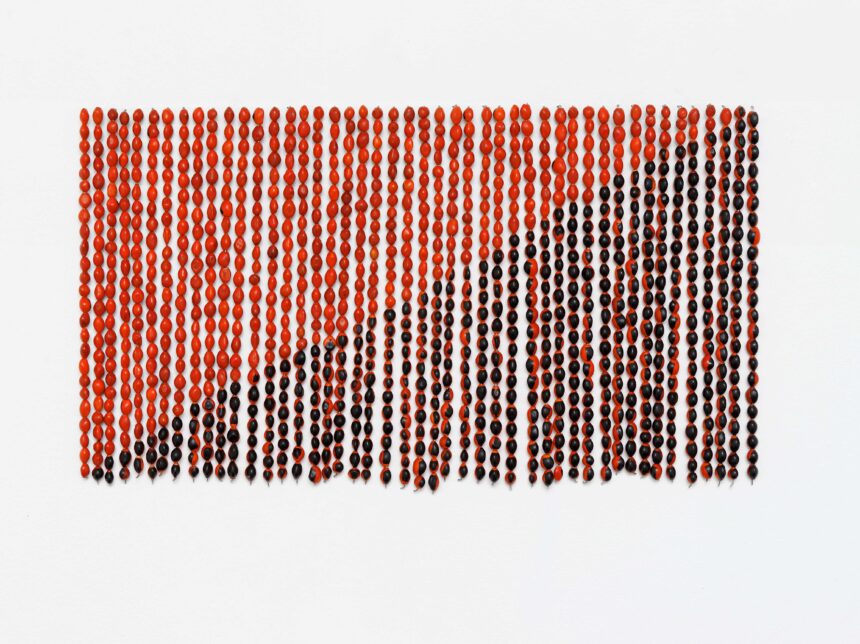

Photo © Aurélien Mole.

Anthropologists such as William Hanks and Carlo Severi, precisely advocate an ‘epistemological space of translation.’[7] Whilst acknowledging the existence of different ontologies, they suggest that these ontologies are not homogeneous, but impure and blended, thus leaving frayed edges with the possibility for communication, and hence translation.[8]

Commenting on two of the key figures in the ontology debate, Philippe Descola’s approach and Eduardo Viveiros De Castro’s ‘perspectivism,’[9] they write:

But what about the grey zones between perspectives or between modes of existence? What of the blending or grading or switching between systems, which surely occurs over the history of colonialism in the Americas, for example? Any typological schema will face the question of blends. And if we use translation to name the process(es) that cross between types, then we will have to deal with blending, and the emergence of new types or varieties. How, then, shall we translate ontologies, given that they are emergent and not static, blended, and not pure?[10]

This recalls a similar critique leveled against the idea of hybridity (in its root concept, meaning the admixture of two ‘originally’ pure forms, as in zoological terminology) by Jonathan Friedman who rightly insisted that there are no pure cultures (or by current extension, ‘ontologies’) ab initio.[11] Jean-Loup Amselle tried to resolve this conundrum by speaking of ‘originary syncretism.’[12]

However, one does not have to delve into the thorny issue of the ‘origin’ of cultures, ontologies, or indeed language, but it is clear that the components of radical difference have to be thought of as already blended, and thus -at least in part– open to translation.

The question then remains, how to fill the ‘epistemological space of translation’ that Severi and Hanks project. For this, they take inspiration from the historian-philosopher Thomas Kuhn who suggests to conceive of scientific communities as speech communities,[13]

…where many forms of translation are constantly carried on, despite the theoretical incommensurability of paradigms. Translation ceases to be defined as an abstract impossibility. The challenge posed by the constant confrontation of ‘incommensurable’ (yet translated) paradigms becomes in itself, on the contrary, a field for ethnographical inquiry.[14]

One more obvious candidate of relevance to the art-anthropology encounter, and beyond Kuhn, I contend, must be hermeneutics – but not in its romanticized view of participants in a philosophical seminar in level philosophical discourse – but as those taking part in a conversation acknowledging differences of all kinds (power, gender, post- and decolonial viewpoints).

***

Recent theorizing around the ‘commons’ – with this are meant the limited resources on the planet (e.g. land, water, air) which belong to all (and not to individuals, private companies or the state – however these are defined) show some of the dilemmas of alterity and translation in political struggle, not least in political attempts to reclaim these resources.

In fact, struggles to retain and regain control over the commons can also be fought on the grounds of difference, or that which is not common, indeed uncommon – a theoretical concept introduced into the debate by Marisol de la Cadena. She makes a strong point about this when she shows how indigenous Quechua-speaking peoples in the Peruvian Andes include mountain spirits, or “earth beings” into the argument and attribute agency independent of humans to them.[15] Government agencies, but also potential allies of indigenous struggles over land and water rights, such as NGOs have to acknowledge this. The challenges facing us are truly global, but we must acknowledge the contemporaneity of difference, which includes alliances and struggles on ‘uncommon grounds,’ or between actors of different world-views.[16]

It is from a criticism of classical hermeneutics that Native American anthropologist Darren J. Ranco asks, “What about those stories that are so other that anthropologists cannot understand them at all?,”[17] refusing a simple understanding of the object and one’s own convictions within the same experiential event, as in Gadamerian hermeneutics. Ranco writes from a decolonial perspective and wants to shift “the privilege away from the outsiders and their knowledge to the insiders and their knowledge.”[18] This is clearly a stance of ‘epistemic disobedience’ long advocated by decolonial scholars such as Walter Mignolo. However, whilst acknowledging for differences in knowledge production, and their historical, including (post) colonial contingency, this still allows for, indeed requires translation in terms of ‘border thinking’ and ‘border epistemologies,’ a point specifically argued by Mignolo.[21]

The understanding of ‘our’ tradition, in which the foundation of philosophical discursive hermeneutics rests, implies that the tradition to be understood and the understanding subject are one and the same; a universal tradition is understood by a universal subject who, at the same time, speaks for the rest of humanity. Contrary to the monotopic understanding of philosophical hermeneutics, colonial semiosis presupposes more than one tradition, and therefore demands a diatopic or pluritopic hermeneutic, a concept I borrow from Raimundo Panikkar.[22]

Indeed, hermeneutics recently has gained some renewed traction in anthropology, especially through the work of Michael Lambek, who made a strong case for a fresh reappraisal. Lambek suggests that Gadamer’s hermeneutics (as laid out in Truth and Method, and other writings) offers the best response to the issue of incommensurability, and “that the very activity of conversation (hence interpretation or translation) may be understood as ethical.”[23] Ethics is an important point for Lambek, who in his essay is occupied with the ‘conversation’ between different moral or religious systems, but also anthropology’s work to interpret these. He writes: “The conversation within hermeneutic philosophy and those within anthropology show similarity to one another on these matters – as indeed does the ethical force of interpretation in our respective traditions.”[24]

Importantly, as Lambek points out, for Gadamer, the hermeneutical principle implied the possibility, if not the necessity, to not only understand the position but also, potentially, to accept superiority of the Other’s viewpoint.[25]

Consequently, the ‘fusion of horizons,’ envisaged by Gadamer, for Lambek does not necessarily mean homogenization but can also imply to mean maintenance of diversity, as Lambek writes: “In fact the metaphor of horizons is one of degree and of partially shared or overlapping perspectives and terms of criteria rather than of submersion into common identity.”[26]

***

It is at this point, perhaps, that a productive confrontation with the pluritopic hermeneutics advocated by Mignolo is possible. At least for the western trained, western based anthropologist this would imply relinquishment of one’s own position, accepting if not the superiority, then at least the intrinsic validity of others’ viewpoints. According to hermeneutic philosopher Paul Ricoeur (writing about ‘appropriation’ in the hermeneutic process) this implies to dispossess oneself of the narcissistic ego, in order to engender a new self-understanding, not a mere congeniality with the other.[27] As he writes, “Relinquishment is a fundamental moment of appropriation and distinguishes it from any form of ‘taking possession.’”[28]

And it is here that I propose a concept of uneven hermeneutics, a way of understanding and learning from the Other that does not occupy its semantic territory.

“Uneven hermeneutics … reappropriates anthropological hermeneutics and puts it to use for contemporary times, without colonizing the thought of the Other.”[29]

The concept of uneven hermeneutics comes out of my practical experience of a collaborative art project in northeastern Argentina, Corrientes province, which involved the negotiation of different forms of doing research with, and making sense of the Santa Ana. Different forms of understanding also arose from differences in educational background and notions of anthropology between the artistic researchers and the anthropologist.[30]

The unevenness of the hermeneutic process, as an inherently unstable enterprise, is made evident from conversations I had with Mati Obregón and Richard Ortíz, the two artists who collaborated in the first phase of the project in 2005.

We were exploring the possibility of showing our work in the provincial Art Museum in Corrientes, and the possibility of bringing sand from the village of Santa Ana (referencing its peculiar feature of leaving roads deliberately unpaved, but having them covered with sand instead).

Mati Obregón: To take sand seems more like a game, but I don’t want to play now. It seems more serious to me to make a PowerPoint presentation and that we talk, rather than to make a show. Were you thinking the same?

Richard Ortíz: No, I rather thought something else. But it’s something personal. This work is a bit like taking advantage of, or exploiting, what I have already incorporated.

Mati: A bit like an ‘auto-vivisection.’ I am not taking advantage of, or exploiting, what I have, I use it.

Richard: The image, the lived experience. To make an artwork about the procession gives me the impression that I am taking advantage of it.

Mati: I think for us this continues to be something sacred.

Richard: That’s what’s happening.

Mati: Because for me the procession, on the one hand, is something completely rational as for any other educated person. However, on the other hand, there is also a part in my being which I regard as very sacred. For instance, I don’t omit making the sign of the cross when I enter a church. I do it sometimes even out of respect for the persons who are there. It’s a very sacred space, and it’s a very fine limit between the sacred place, the other, and myself, when I take part in this procession.

Richard: It’s like putting these very sacred things, which we have lived with since we had consciousness, and then suddenly to transfer them to the art world.

[…]

Mati: This process affects me now. Because you [Arnd] came and mobilized us in order to enter a process of auto-ethnography. And I came and started to see what I was very familiar with, to see it again in a more detailed fashion – I am myself from this area. I came a thousand times to Santa Ana. I don’t know the names of all the people you [Arnd] now know, but I know the life of Doña Petra who was the shopkeeper on the corner of the house of my friend, the life of another shopkeeper – well, I know this place. And to come back and see, I am in fact looking at myself. So, it’s really a new process I am experiencing in this project. I don’t know what will be the outcome. There will be a procession, sure, but we want to put for all the people a protection, a protection against the alien eye. I don’t want to be touched, I don’t want to be seen, the same the people felt who didn’t want to be recorded – you felt it also now, I don’t want that they see me.

Arnd: This we have to respect, we are not doing the project with a hidden agenda. Similarly, with the taking of photographs, some even approach us directly, they want to be interviewed.

Mati: This is the process of the gaze toward the other, and we are now also experiencing it. Up to what point I show myself, the difference between private and public, of what I want they see, and what I am familiar with, and what your eye as an anthropologist sees; of what a scholar from another culture finds in my inner self, in my culture which is myself. So, one feels as if one is delivering one’s treasured own being. It’s very strange – I never put this to myself.

Richard: Many things are happening to me now. From now on, it might even be that I take another direction in my work.

Arnd: But you see this as something positive ….?

Mati: Like a change, as something very strange.

Arnd: Like a challenge?

Mati: It’s something strange, after I open myself more, I show myself more, because it’s good to get to know each other, this is the only way to understand each other in this world, and so we can reach something like a ‘communion,’ or mutual respect. Like somebody who reveals herself slowly. I don’t know what my work will turn out to be. Here is everything I have lived.

Mati returned to this point at our public discussion as part of the opening of the exhibition:

Mati: First of all, I found myself observed like a strange being. I felt they were to take my soul, as the people must have felt whom Arnd approached to record, and sometimes did not want to. At one stage, I said I will do this and I could make any artwork from this, but I felt observed and that I was delivering my most private secrets. This I didn’t like – I don’t know about Richard…

Richard: What happens with this project is that he [Arnd] wants that we put in all our experiences which we had and to do it quickly from one day to the next it’s something a bit forced, a mere illustration. This is one of my preoccupations when making contemporary art.

Mati: So for me to make a work of art about Santa Ana to show it to somebody, for me it’s like an aberration. Not knowing what to do, I started collecting things in the fiesta. I collected the little medals they sell in the plaza. I started to work like an anthropologists. I can tell him the story of my life, my feelings, but he didn’t come to look for this.

Richard: I think he looked for us like some translators.[31]

The conversations clearly show that we were entangled in a two-way conceptual, yet uneven process of translation. The discussions between us revealed fragmentary, and contested notions of each other’s practices. However, in a gradual process both sides learned from each other, to achieve a complementary understanding.[32]

More profoundly, the project resulted for the artists in a complex and contradictory process about the revelation of content (something they considered ‘sacred’ in Mati Obregón’s words), or release of meaning, and negotiating it as translators or conductors of meaning in conjunction with the anthropologist who, in turn, was charged with translating meaning to arrive at understanding.[33]

Hence, this project – which stands in here for other situations of uneven hermeneutics in the art-anthropology encounter – throws us back to the possibilities and impossibilities of translation, but which maintain the dialogical principle.

Uneven hermeneutics would also speak to the ‘dialogical aesthetics’ advocated by Grant Kester. Kester builds critically on Habermas’ speech act and theory of communicative action, and also on Gemma Fiumara’s concept of ‘listening,’ by explicitly acknowledging the differences between those engaged in any ‘dialogue,’ that is cultural workers, artists and communities; or in our case, artists and anthropologists, and their subjects in the mise-en-scène of ethnography.

For the art – anthropology encounter then, the dialogical principle stands paramount. This returns us to the ‘speaking terms,’ taken from Clifford, with which I opened this essay. There can be no a priori demands to fill this, only – as in hermeneutic discourse, and through the cumbersome and arduous work of translation – carefully tuned negotiation, and understanding, respecting the incommensurable, and making it productive for future dialogues.

Arnd Schneider is a Professor of Social Anthropology, University of Oslo where he researches and teaches on contemporary art, visual anthropology, and international migrations. He is a collaborative partner of “TRACES: Transmitting Contentious Cultural Heritages with the Arts” funded under the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme. His books include Futures Lost: Nostalgia and Identity among Italian Immigrants in Argentina (Peter Lang, 2000) Appropriation as Practice: Art and Identity in Argentina (Palgrave, 2006), and most recently, Alternative Art and Anthropology: Global Encounters (edited; Bloomsbury, 2017). He co-organized the international conference “Fieldworks: Dialogues between Art and Anthropology”, at the Tate Modern, London (2003), and the symposia “Performance, Art and Anthropology” (2009) and “New Visions: Experimental Film, Art and Anthropology” (2012) at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris. He has taught at the University of East London and been a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Hamburg.

Endnotes

[1] James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Surrealism,” in The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988): 126.

[2] Ibid.

[3] James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Surrealism;” also Arnd Schneider, “Unfinished Dialogues: Notes Toward an Alternative History of Art and Anthropology,” in Made to Be Seen: Perspectives on the History of Visual Anthropology, ed. Marcus Banks and Jay Ruby (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011). For a recent attempt by visual anthropologist Alyssa Grossman and artist Selena Kimball to work with surrealist techniques in the ethnographic archives of museums, see Alyssa Grossman, “Counter-Factual Provocations in the Ethnographic Archive,” OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform, no. 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/counter-factual-provocations-ethnographic-archive/(accessed February 16, 2018).

[4] Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London and New York: Verso, 2013), 17, 26.

[5] Arnd Schneider, “Alternatives: World Ontologies and Dialogues between Contemporary Arts and Anthropologies,” in Alternative Art and Anthropology: Global Encounters, ed. Arnd Schneider (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2017), 2-4.

[6] Ibid., 4-9.

[7] William F. Hanks and Carlo Severi, “Translating Worlds: The Epistemological Space of Translation,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4, no. 2 (2014): 1–16.

[8] Ibid.: 8.

[9] Philippe Descola and Marshall David Sahlins, Beyond Nature and Culture, trans. Janet Lloyd (Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013 [2005]); Eduardo Viveiros De Castro, “Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4, no. 3 (1998): 605–632.

[10] Hanks and Severi, ibid.: 8-9.

[11] Jonathan Friedman, “Global Crises: The Struggle for Cultural Identity and Intellectual Porkbarrelling. Cosmopolitans versus Locals, Ethnics and Nationals in an Era of de-Hegemonisation,” in Debating Cultural Hybridity: Multicultural Identities and the Politics of Anti-Racism, ed. Pnina Werbner, Tariq Modood, and Homi K. Bhabha, Critique, Influence, Change (London: Zed Books, 1997); and “The Hybridization of Roots and the Abhorrence of the Bush,” in Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World, ed. Mike Featherstone and Scott Lash, Theory, Culture & Society (London: Sage, 1999).

[12] Jean-Loup Amselle, Mestizo Logics: Anthropology of Identity in Africa and Elsewhere, (Mestizo Spaces) (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998).

[13] Thomas S. Kuhn, The Road since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970 – 1993, with an Autobiographical Interview, ed. James Conant and John Haugeland (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 166.

[14] Hanks and Severi, ibid.; 6

[15] Marisol de la Cadena, “Uncommoning Nature,” E-Flux Journal SUPERCOMMUNITY, May-August (2015), http://supercommunity-pdf.e-flux.com/pdf/supercommunity/article_1313.pdf (accessed February 16, 2018); and Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), esp. chapter 2. In Aereotora, New Zealand, several mountains have been granted ‘legal personality’ and thus the same legal rights as a person, most recently Mount Taranaki, “Mount Taranaki Granted Legal Rights,” The Guardian Weekly, January 5, 2018, 3.

[16] Schneider, ibid., 14.

[17] Darren J. Ranco, “Toward a Native Anthropology: Hermeneutics, Hunting Stories, and Theorizing from Within,” Wicazo Sa Review 21, no. 2 (2006): 61–78.

[18] Ibid., 73.

[19] Walter D. Mignolo, “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom,” Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 7–8 (2009): 1–23.

[20] Miranda Fricker, Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); also, Andrea J. Pitts, “Decolonial Practice and Epistemic Injustice,” in The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice, ed. Ian James Kidd, José Medina, and Gaile Pohlhaus Jr., Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy (London; New York: Routledge, 2017).

[21] See Walter D. Mignolo and Freya Schiwy, “Transculturation and the Colonial Difference: Double Translation,” in Translation and Ethnography: The Anthropological Challenge of Intercultural Understanding, ed. Tullio Maranhão and Berhard Streck (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2003), 15; also, Walter Mignolo, The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995); and Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking, Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000).

[22] Mignolo, The Darker Side of the Renaissance, p. 11. See also Raimundo Panikkar, “Cross-Cultural Studies: The Need for a New Science of Interpretation,” Monchanin 8, no. 3–5 (1975): 12–15; and “What Is Comparative Philosophy Comparing?” in Interpreting Across Boundaries: New Essays in Comparative Philosophy, ed. Gerald James Larson and Eliot Deutsch (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

[23] Michael Lambek, “The Hermeneutics of Ethical Encounters: Between Traditions and Practice,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 5, no. 2 (2015): 227–250, here page 228 ; see also his “‘Tryin’to Make It Real, but Compared to What?,’” Culture 11, no. 1–2 (1991): 29-38, and Filipe Verde, “Astrólogos e Astrónomos, Nativos e Antropólogos: As Virtudes Epistemológicas Do Etnocentrismo,” Etnográfica, no. 2 (2003): 305–319. [Available in English as: “Truth as the Critical Edge: Gadamer’s Hermeneutics and Anthropological Knowledge,” http://iscte.academia.edu/FilipeVerde/Papers (accessed 9 Februrary 2018)]. For Gadamer, the principal references are: Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. Garret Barden and John Cumming (London: Bloomsbury, 1985 [1969]); and Philosophical Hermeneutics, trans. Robert R. Sullivan (Cambridge Mass: MIT press, 1976).

[24] Lambek, “The Hermeneutics of Ethical Encounters”, 228.

[25] Ibid.: 229

[26] Ibid.: 231

[27] Ibid.: 243

[28] Paul Ricœur, Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences: Essays on Language, Action, and Interpretation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 191-193.

[29] Ibid., 19

[30] Schneider, ibid., 15.

[31] This conversation extract has also been used in Arnd Schneider, “Contested Grounds: Fieldwork Collaborations with Artists in Corrientes, Argentina,”

Critical Arts 27, no. 5 (2013): 511 – 530, here 515 -516.

[32] Schneider, ibid.: 515 – 516.

[33] Schneider, ibid.: 520. Cf. Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 82 – 123, esp. p. 106. The references are to Jürgen Habermas, Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, trans. Christian Lenhardt and Shierry Weber Nicholsen, Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991); and Gemma Corradi Fiumara, The Other Side of Language: A Philosophy of Listening (New York: Routledge, 1995).

Bibliography

Amselle, Jean-Loup. Mestizo Logics: Anthropology of Identity in Africa and Elsewhere. Mestizo Spaces. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Cadena, Marisol de la. Earth Beings: Ecologies of Practice across Andean Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

———. “Uncommoning Nature.” E-Flux Journal SUPERCOMMUNITY, May-August (2015). http://supercommunity-pdf.e-flux.com/pdf/supercommunity/article_1313.pdf.

Clifford, James. “On Ethnographic Surrealism.” In The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Corradi Fiumara, Gemma. The Other Side of Language: A Philosophy of Listening. New York: Routledge, 1995.

De Castro, Eduardo Viveiros. “Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4, no. 3 (1998): 469–488.

Descola, Philippe, and Marshall David Sahlins. Beyond Nature and Culture. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2013 [2005].

Fricker, Miranda. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Friedman, Jonathan. “Global Crises: The Struggle for Cultural Identity and Intellectual Porkbarrelling. Cosmopolitans versus Locals, Ethnics and Nationals in an Era of de-Hegemonisation.” In Debating Cultural Hybridity: Multicultural Identities and the Politics of Anti-Racism, edited by Pnina Werbner, Tariq Modood, and Homi K. Bhabha. Critique, Influence, Change. London: Zed Books, 1997.

———. “The Hybridization of Roots and the Abhorrence of the Bush.” In Spaces of Culture: City, Nation, World, edited by Mike Featherstone and Scott Lash. Theory, Culture & Society. London: Sage, 1999.

Gadamer, Hans Georg. Philosophical Hermeneutics. Translated by Robert R. Sullivan. Cambridge Mass: MIT press, 1976.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. Translated by Garret Barden and John Cumming. London: Bloomsbury, 1985 [1969].

Grossman, Alyssa. “Counter-Factual Provocations in the Ethnographic Archive.” OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform, no. 2 (2017). http://www.oarplatform.com/counter-factual-provocations-ethnographic-archive/.

Habermas, Jürgen. Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Translated by Christian Lenhardt and Shierry Weber Nicholsen. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1991.

Hanks, William F., and Carlo Severi. “Translating Worlds: The Epistemological Space of Translation.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4, no. 2 (2014): 1–16.

Kester, Grant. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Road since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970 – 1993, with an Autobiographical Interview. Edited by James Conant and John Haugeland. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Lambek, Michael. “The Hermeneutics of Ethical Encounters: Between Traditions and Practice.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 5, no. 2 (2015): 227–250.

———. “‘Tryin’to Make It Real, but Compared to What?” Culture 11, no. 1–2 (1991): 29–38.

Mignolo, Walter. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000.

———. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

Mignolo, Walter D. “Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom.” Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 7–8 (2009): 1–23.

———, and Freya Schiwy. “Transculturation and the Colonial Difference: Double Translation.” In Translation and Ethnography: The Anthropological Challenge of Intercultural Understanding, edited by Tullio Maranhão and Berhard Streck, 3–29. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2003.

“Mount Taranaki Granted Legal Rights.” The Guardian Weekly, January 5, 2018.

Osborne, Peter. Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art. London and New York: Verso, 2013.

Panikkar, Raimundo. “Cross-Cultural Studies: The Need for a New Science of Interpretation.” Monchanin 8, no. 3–5 (1975): 12–15.

———. “What Is Comparative Philosophy Comparing?” In Interpreting Across Boundaries: New Essays in Comparative Philosophy, edited by Gerald James Larson and Eliot Deutsch, 116–36. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Pitts, Andrea J. “Decolonial Practice and Epistemic Injustice.” In The Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice, edited by Ian James Kidd, José Medina, and Gaile Pohlhaus Jr. Routledge Handbooks in Philosophy. London; New York: Routledge, 2017.

Ranco, Darren J. “Toward a Native Anthropology: Hermeneutics, Hunting Stories, and Theorizing from Within.” Wicazo Sa Review 21, no. 2 (2006): 61–78.

Ricœur, Paul. Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences: Essays on Language, Action, and Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Schneider, Arnd. “Alternatives: World Ontologies and Dialogues between Contemporary Arts and Anthropologies.” In Alternative Art and Anthropology: Global Encounters, edited by Arnd Schneider. London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2017.

———. “Contested Grounds: Fieldwork Collaborations with Artists in Corrientes, Argentina.” Critical Arts 27, no. 5 (2013): 511 – 530 .

———. “Unfinished Dialogues: Notes Toward an Alternative History of Art and Anthropology.” In Made to Be Seen: Perspectives on the History of Visual Anthropology, edited by Marcus Banks and Jay Ruby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Verde, Filipe. “Astrólogos e Astrónomos, Nativos e Antropólogos: As Virtudes Epistemológicas Do Etnocentrismo.” Etnográfica, no. 2 (2003): 305–319. [Available in English as: “Truth as the Critical Edge: Gadamer’s Hermeneutics and Anthropological Knowledge.” http://iscte.academia.edu/FilipeVerde/Papers (accessed 9 Februrary 2018)].