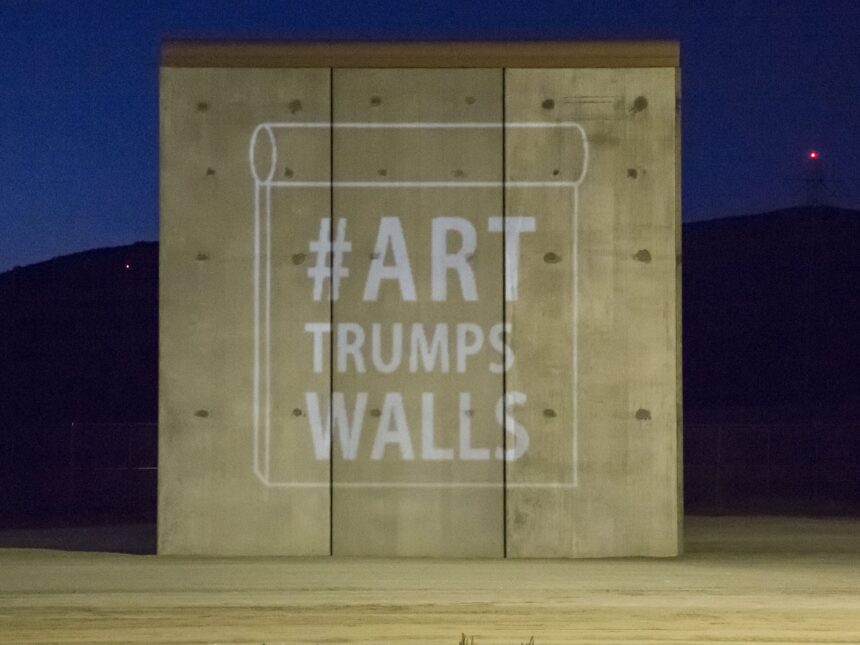

Art Trumps Walls

Andrew Sturm

The border wall prototypes constructed in San Diego / Tijuana to fulfill President Trump’s campaign promise are a type of political theatre, a sleight-of-hand to redirect attention at an “immigrant problem” that does not exist while his administration carries out its xenophobic agenda. Art Trumps Walls literally shines light on this issue, transgressing the current US / México border wall to trespass on Trump’s political theatre with visual narratives that challenge the President’s divisive rhetoric. These narratives came from youth living near the border. The Art Trumps Walls action provided a platform to amplify their voices and project them into the discourse surrounding the border wall. This work happened during a particular historical moment in the United States: youth around the country are raising their voices in protest to demand common-sense gun regulations, inspired by the survivors of the massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Right now, young people are sending some of the clearest and most compelling messages into the otherwise polarized madness that adults have allowed to fester.

During the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump made building a “big, beautiful wall” across the southern border of the United States a central campaign promise. Once elected, his administration put out a request for proposals and eventually selected eight potential border wall designs. As part of the selection process a physical prototype of each design was constructed at a location just east of Otay Mesa, a neighborhood of San Diego, California that runs along the border with Tijuana, México. The selected site placed the prototypes in line with a secondary border fence, about 125 feet north of the original corrugated steel border wall, which was constructed in the 1990s and still exists.

Each border wall prototype is roughly 30 feet tall and 30 feet wide. The prototypes are arranged with gaps between them in a dashed line extending east, away from Otay Mesa and out into the desert. On the U.S. side, temporary fencing, vehicle barriers and “no trespassing” signs have been installed to create a secure perimeter about a mile and a half from the prototypes. The only way to see the prototypes from the United States is with a strong pair of binoculars or a telephoto lens. By contrast, from the México side, the hulking wall segments feel almost close enough to touch.

In October 2017, I visited the prototypes as part of a tour led by Tijuana-based artist and photographer Jill Marie Holslin, along with a group of visiting architects and journalists. Jill outlined the history of the various border walls, and her practice, which has been focused on the Tijuana / San Diego border for over ten years. While the group took photographs and dimensions, I spoke to Holslin about how the prototypes resembled billboards or drive-in movie screens and how they might be engaged artistically to challenge their oppressive presence.

Not long after this visit an activist group, Overpass Light Brigade, approached Holslin to discuss a project they were considering, and we decided to work together to create a series of light projections on the prototypes. In mid-November 2017 the group assembled in Tijuana and used a large theater light with gobo stencils to project light graffiti over the existing steel border wall and onto the prototypes. The projected icons ranged from messages that welcomed refugees, to a luchador mask, to a 31 foot tall ladder. The action received press coverage from more than a dozen prominent outlets across the United States and México for using art as a form of resistance against the Trump regime including the LA Times, USA Today, New York Times, Reforma and Milenio. [1]

Following this success, Holslin and I were approached by border art curator Alessandra Moctezuma, and introduced to Perry Vasquez, an artist and professor of visual art at Southwestern College in Chula Vista, CA, which is very close to the border. Following the conversation, Holslin, Vasquez and I decided to work together with his student artists on a new action that became known as Art Trumps Walls.

We spoke to Vasquez’s students about the histories of politically engaged art practices, the history of the border wall itself, and what it might mean for them to engage with the prototypes as canvases for their messages. Vasquez worked with them for several weeks while they prepared multiple drafts of their proposals, and twenty-three different designs were created by seventeen student artists. A large majority of them identify as Latinx and several live in Tijuana although they attend college in the U.S. Many of the student artists shared in discussions that the toxic immigration rhetoric of the Trump administration feels directed at them, their friends and family, and they wanted to use this project as a way to challenge the President’s xenophobic narrative.

On Saturday, April 7, 2018, Vasquez, Holslin and I met with several students, their families, journalists, and other guests in Tijuana to set up for the projection. That evening the otherwise omnipresent Customs and Border Patrol agents were noticeably absent, but on the Tijuana side, youth on four wheelers raced up and down the dirt road adjacent to the wall as the sun set over the pacific in the distance. The designs from the student artists were arranged in series, like a silent film, and played as the assembled group looked on and cheered.

[nemus_slider id=”2497″]

The projections involved several different themes. Carlo D. created a trampoline graphic, with the words “use in case of wall”, and a second graphic with a family in an elevator, underscoring that the walls would be creatively transgressed regardless of how high the U.S. builds them. Some of the artists’ projections simply reflected core values of the United States, a theme picked up from Holslin’s work, which is perhaps best shown by Brooke H. in her melting pot graphic. Cristy D. showed President Trump as the Statue of Liberty with a torch made from a stack of burning dollar bills, to emphasize that the wall would be an economic waste. Nicholas A. created a graphic based on the concept of the hidden 93/4 train platform from Harry Potter, replacing Harry’s owl with the eagle and snake from the Mexican flag. Some of the artists integrated idioms, including Le’Toya J., who created a series of faces saying “ojos que no ven, corazon que no signet”– what the eyes don’t see, the heart does not feel – the idea that something is easily forgotten or disregarded when not visible. For Le’Toya this was about how the U.S. has turned its back on its neighbor and the many refugees who seek asylum every day at the Tijuana crossing. Another phrase, “traemos el nopal en la frente” – we wear the cactus on our foreheads – is often spoken between Mexicanos to those among them who have become Americanized, reminding them that they are still Mexicano. When the nopal graphic was projected on the border prototype, Raquel N. felt it could be understood as a reference to how California was once a part of México, and how building this new wall would only further reinforce the notion some Mexicanos have that the US feels it is better than México. One last common theme was perhaps best represented by Alejandro E. in his Let Us Love, which was meant as a call for people to come together in the face of the wall’s divisive message.

We see this work in sharp contrast to projects like Christopher Büchel’s, which attempted to reframe the prototypes from afar as historical land art. Through a website which was promoted by super gallery Hauser + Wirth, Büchel asked visitors to sign a petition to have the prototypes declared a national monument and sold tickets for bus tours of them. His project was heavily criticized as being an example of how contemporary art is “concerned more with spectacle and irony than critically dismantling oppressive structures that undermine the lives of the most vulnerable…” [2] Our work with the Southwestern College student artists diverges from work like this by engaging and pulling its narratives from some of the very communities that the wall is meant to exclude and oppress. In this way our project performs as a more socially engaged and locally situated alternative, more aligned with the performances of Augusto Boal’s Theater of the Oppressed, than projects like Büchel’s.

Andrew Sturm is an artist and architect, and recent MFA graduate from UC San Diego.

Full list of participating student artists:

Daphne A., Edgar A., Nicholas A., Alejandro C., Carlo D., Cristy D., Alejandro E., Arturo G., Brooke H., Le’Toya J., George L., Kiara M., Raquel N., Ricardo P., Michelle R., Kevin T., Abby W.

Notes:

[1] See Kate Morrissey, “Border wall prototypes become canvas for light graffiti,” Los Angeles Times, November 22, 2017; Tim Arango, “In Clash Between California and Trump, It’s One America Versus Another,” New York Times, January 7, 2018; Alden Woods, “Activist artist flashes messages of protest on Trump border-wall prototypes,” USA Today, November 22, 2017; Gael Montiel, “Invaden Grafitis Muros,” Reforma, November 24, 2017; “Con graffiti virtual ‘pintan’ los prototipos del muro”, Milenio, November 23, 2017.

[2] Maximilíano Durón, “Artists, Curators Respond to Christoph Büchel’s Border Wall Project,” ArtNews, February 7, 2018.