We Are Everywhere!: On Oliver Ressler’s Video Installation Everything’s Coming Together While Everything’s Falling Apart.

Julia Ramírez-Blanco

After that huge climate march, I asked Jamie Henn, a co-founder of and communications director for 350.org, how he viewed this moment and he replied, “Everything’s coming together while everything’s falling apart.” – Rebecca Solnit

Capitalism has always depended on fossil fuels. Today, despite the scarcity of resources, those running the system do not want to stop its expansion. Ignoring climate change, they continue to construct energy mega-structures all over the world, often destroying local communities together with their habitats. Researchers are now pointing out that the resulting loss of biodiversity and the shattering of natural ecosystems create precisely the conditions for diseases such as COVID-19 to emerge. If things do not change, the “Capitalocene” might turn out to be an age of epidemics and pandemics. Points of resistance to ecological damage are sprouting all over the globe. The Environmental Justice Atlas (ejatlas.org) provides information on around 3,000 socio-ecological conflicts among the tens of thousands that it estimates are taking place right now. The recent work of Austrian artist Oliver Ressler has focused on this kind of struggle. In the six videos that comprise his video installation Everything’s coming together while everything’s falling apart (2016-2020), he puts together different examples of activism against the fossil-fuel economy. For him, these stories from the climate-justice movement “may turn out to be a story about the beginning of the climate revolution.”

Filming the climate movement

For twenty years, Ressler´s work dealt with social movements in different parts of the world. Climate conflicts appeared early in his work: in both 100 Years of Greenhouse Effect (1996) and Sustainable Propaganda (2000), he criticized capitalism’s technocratic approach to the ecological crisis and its promised solutions of what we now call green capitalism. With his billboards entitled Failed Investments (2015), Ressler linked real-estate speculation with the environmental crisis, and his film Leave it in the Ground (2013) denounced undersea extractivism. But the direction of his work changed with the installation For a Completely Different Climate (2008), in which the artist dealt directly with climate activism for the first time. For this project, Ressler created an installation using photographs and sounds that he recorded at the Climate Camp organized that summer near the Kingsnorth coal-fired power station in Ashford, Kent in the UK.

Activists managed to temporarily block the existing power station and to prevent the construction of a new one in the same place. Climate camps are a form of political protest that emerged in the UK in 2006 and they have since spread throughout the world. These camps function as communities of resistance and coexistence, working as a base for environmental direct action and providing spaces for meetings, workshops, and social life. They also constitute places of radical democracy, where other possible societies are sketched out. Thus, Ressler’s interest in them foreshadowed the utopian drive that characterized his subsequent series on climate activism, in which the struggle and the construction of alternatives go hand in hand.

Everything’s coming together

Oliver Ressler began his video series Everything’s coming together while everything’s falling apart in 2015 with a trip to the Paris COP21 climate conference, following the mobilizations in the street. Thus, he began a practice of filming different moments of climate activism and then shaping the narrative at the editing desk. The six videos that make up the series correspond to six times and places where environmental activism was successful in one way or another. This strategic optimism is centered on the idea that the movements can win. Ressler emphasizes this diagnosis in the description of the series: “The title (. . .) refers to a situation in which all the technology needed to end the age of fossil fuel already exists. Whether the present ecological, social, and economic crisis will be overcome is primarily a question of political power. The climate movement is now stronger than ever.”

Places and actions

Each of the six videos covers a time and place of activism and community organization. In a sense, most of them function as a kind of journey for the spectators.

The first of the videos (COP21, 2016, 17 min.) was filmed by Ressler during the United Nations Climate Conference (COP21) in Paris in December 2015. Instead of recording the meetings between leaders who, as Ressler remarks in the film, were not really looking for an agreement, the film focuses on protestors. We see the inflatable cobble-stones designed by the Tools for Action collective, and listen to the words of John Jordan, an artist-activist who played an important role in the global-justice movement. On a stage during the protests Jordan presents the direct-action Red Lines, organized on the basis of a consensus reached by 150 organizations.

Ressler’s film is narrated by a woman’s voice, the political writer and activist Renée Gadsen, who reads texts written by Ressler in collaboration with Matthew Hyland. The narrator’s interventions are poetic and range from the apocalyptic to radical optimism. We also see images of the festive atmosphere of the protest––beautiful banners, a batucada in the street, and people dressed in red and pink, dancing. The culture of the movement also implies a celebration of diversity, expressed by certain music, forms of dress, and chants. One of the most recognizable symbols of the environmental movement in Europe––the use of white overalls––would become a key feature of Ressler’s next video.

A central action of the European environmental movement is the occupation of open-pit coal mines. The second video (Ende Gelände, 2016, 12 min.) follows a 2016 action in the Welzow-Süd open-pit mine in Brandenburg, Germany. Its participants are part of Ende Gelände (meaning “Thus far and no further”), a movement that emerged in 2015 from a coalition of German environmental groups, and which focuses on blocking coal mines. While its iconic image of people wearing white overalls and masks relates to protecting the body, on an unconscious level it also evokes images of dystopian disaster. Upon arriving at the mine, we see the contrast between the white suits of the activists and the blackness of the environment. They are successful in a two day blockade: during the 48 hours of confrontation about 4,000 activists from different countries blocked the open-pit coal mine, and the coal-fired power station was cut to 20% of its power for two days. The narrator talks about the need for a change in the ways of living.

The third film in the series (The ZAD, 2017, 36 min.) shows a place where this has already taken place. In it, Ressler focuses on the largest autonomous area in Europe. The story of the ZAD (zone à défendre: in French, zone to defend) begins with the opposition of farmers to an airport project in Notre-Dame-des-Landes, near Nantes. In 2009, activists organized a Climate Action Camp, joining the struggle and eventually settling down to live in the area, building a village called “La Châtaigne”. There, a diverse community of 250-300 inhabitants governed itself through a system of direct democracy and consensus-based agreement. Ressler’s camera films conversations between activists and also shows us the beauty of the place: we look at the meadows, the self-made houses, and the library. The video ends with the voices of activists Isabelle Fremeaux and John Jordan. The latter´s words could be taken as a summary of the meaning of this video and of Ressler’s whole series: “You have to create alternatives while you resist at the same time.” As we hear this, the camera is moving away, along the road, leaving the ZAD behind.

After the release of Ressler’s film, in January 2018, under the presidency of Emmanuel Macron, the French government declared that it was abandoning the airport project, representing a great victory for the movement. However, a series of extremely violent evictions from the ZAD began in April of that year. Today, there are about 200 people living there, but while 350 hectares of the land are legalized, the houses continue to be illegal. The intention of some of the activists is to reclaim the land and make the area function as a commons.

The fourth video (Code Rood, 2018, 14 min.) focuses on the civil-disobedience action that took place in June 2017 at the Amsterdam coal port––the second largest coal port in Europe – now privately owned. Again, we see activists arrive in white overalls decorated in a DIY manner. In this film we see them in action: standing on the conveyer belts, locked onto the cranes, and blocking the port. Although the voice of the narrator here has a somber, apocalyptic tone, the video ends with activists singing “Power to the People”.

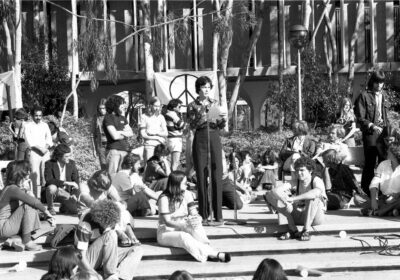

The fifth video (Limity jsme my, 2019, 10 min.) begins with a landscape seen from a prisoner transport truck operated by the Czech police. It is actually from Ressler’s perspective, as a prisoner in the truck: he was arrested in the course of filming this event of direct action. In the film we see the Bílina coal mine in the Czech Republic: activists of the Czech movement Limity jsme my (“We are the limits”) conducting direct action. Created in 2015, this group defines itself as “an open grassroots civic movement against coal mining and coal burning”: Ressler portrays them singing while sitting on the ground.[image 7] The camera also records the presence of the police, who urge them not to act. Off-camera, the activist group carried out a blockade of the mine, which was followed by a mass arrest.

The last video in the series (Venice Climate Camp, 2020, 21 min.) takes us to the first climate camp organized in Italy, in September 2019 in Venice. The film then shows us how these activists occupied the red carpet of the Venice film festival, dressed in white overalls and displaying banners. In fast-moving footage, we see them spend the night there as we listen to their slogans. When dawn breaks, many more people arrive, joining the protest. Different people speak, although the camera focuses more on those who listen.

United in a single installation, the six videos form a geographical polyphony, creating a simultaneous narrative of actions taking place around Europe. Through its installation form–in which the films and actions surround the viewer–Everything’s coming together while everything’s falling apart presents the climate movement as a global movement, just as the global-justice movement was intended to be. Although the chronological placement of the videos allows us to observe an evolution in the movement, the public’s perception is often one of simultaneity. The videos thus function as chapters in a larger story that is still being written.

New armies

In each of the six videos, the voices of the narrator and the activists continually insist on the need for a collective response to the climate crisis. Responsible individuals are not enough: governments and big business will change only if they are forced to. The very way in which the videos are structured also responds to this idea of the collective. In an interview with Maja and Reuben Fowkes, Ressler explained: “In more recent years I have tried to avoid having a single person in front of the camera ( . . .) Because the social transitions needed for planetary survival must be brought about democratically, it is important to present the democratic processes of group discussions in films.”[1] This interest in the collective activist body is also manifested in Ressler’s work New Model Army (2016-17), in which several life-size mannequins representing activists carry different banners. One of them is a polar bear, another is an activist from Ende Gelände, and the third one is dressed in red referring to the climate movement axiom “Be the Red Line”. With these ghostly figures sneaking into the exhibition space, Ressler seems to be inviting us to step out of the white cube and join the struggle, in a fight that will define the future.

Julia Ramírez-Blanco is lecturer at Barcelona University. Art historian and critic, she has specialized in the relationships between art and utopia, to which she dedicated her European PhD thesis (2015). Her recent work has focused on the intersection between art, social imagination and activism. She is author of the book Artistic Utopias of Revolt: Claremont Road, Reclaim the Streets, the City of Sol (New York, London: Palgrave, 2018) previously published in Spanish as Utopías artísticas de revuelta. Claremont Road, Reclaim the Streets, la Ciudad de Sol (Madrid: Cátedra, 2014). Her articles have appeared in English, French, Italian, and Spanish within various co-authored books and in journals such as Third Text, Arquitectura Viva, Quintana, Lars, Boletín de Arte, El Mundo, Abc Cultural, and The Nation Journal. She is co-curator of the exhibition THE GRAND DOMESTIC REVOLUTION (Familistère, Guise, 2019, together with Sally Bonn and Lise Lerichomme). She collaborates regularly with the MACBA Museum of Contemporary Art, where she will direct the course Utopian nineties (2020), as well as directing the Research group on the collection. She has lectured in many international universities and art institutions, including Princeton University, Columbia University, the Reina Sofía Museum, the Prado Museum, or the Warburg Haus Frankfurt, among others. Currently, she is working on a book about the history of artist collectives.

Notes:

[1] “Oliver Ressler: Gathering around the Wreckage”, Dejan Vasić (Ed.), Belgrade: Cultural Centre of Belgrade, 2020.