Street Solidarity: A Report on Lebanon’s ‘October Revolution’

By Erin E. Cory

Beirut’s walls are noisy.

Since the Lebanese civil war (1975-1991), the city has been a growing cacophony of the various insignia – graffiti, political posters, flyers – of militias and their respective political parties (Maasri 2009). Significant numbers of stencils in a given area designate the neighborhood as belonging to a particular ethnoreligious group. In the in-between areas – the stretches of street, highway, and alleyway between neighborhoods – local and regional debates go on in quick-scrawl graffiti. Anonymous edits happen: ‘Syria wants Assad’s neck!’ becomes ‘Syria wants Assad, and that’s it!’

The city has had its street art superstars, including hip hop entrepreneurs Omar and Mohammed Kabbani, known collectively as Ashekman; Yazan Halwani; and the REK crew. Drawing on NYC-based traditions like throw-up graffiti, or incorporating traditional calligraphy into public murals of Arab icons like well-known Lebanese singer Fairuz, these artists combine style with function: their colorful art (re)marks (on) the pockmarked postwar city. Theirs is a kind of street-style beautification project, which uses the detritus of war as canvas, inspiration, texture, and challenge.

Beirut’s street artists also borrow the territoriality and machismo of their 70s-era Stateside forebears, piling their tags on top of one another, calling police if they catch rivals covering up their larger pieces, and rarely crossing into other neighborhoods. They paint here, but not there. Say this and not that. And to be sure, what can be said, and what must never be, carefully scripts the visual culture of the city.

In 2012, the Beirut Art Center, in the wake of the Arab Uprisings, debuted an exhibition called ‘White Wall.’ Curators brought in murals by artists from countries swept by the revolutions. Visitors to the gallery were met with a striking collaboration by several of Beirut’s street artists, the very same crews who challenged each other, who had never worked together before. The walls were a chorus of stylized letters. Of the experience, one of them told me later: “It was the first time we could get really political, and feel safe.”[1] They were given materials (quality paint can be expensive) to take out into the city, and after their pieces were finished, they boarded a bus with exhibition attendees and narrated the city and its art for them. Soldiers sometimes peered into the bus as it idled in front of the pieces, but they never asked what it was doing in these odd spots by the side of the road.

If the art touched on anything political, it was not immediately obvious. And besides, the artists were safe, working within the confines of Beirut’s bourgeois art world, which protected them in the absence of anonymity.

Intervention. Reaction. Erasure. Intervention. Preservation?

The movement between these stages in the life of Beirut’s street art echoes across West Asia and North Africa, among other regions. Throughout the Arab Uprisings, activists, artists, and academics roundly praised, examined, and recorded the myriad artistic actions carried out by protestors across the Arab world. While these actions included music, chants, poetry, and public theater, it was the bright, bold images of the uprising’s street art that seemed to circulate with the most energy, through mass and social media alike.

As Mark LeVine notes, while such images captivated global audiences and observers, they have long been widespread across the Arab world (Levine 2015). The walls in the West Bank and Gaza, for example, have since the First Intifada (1987-1993) been used to record messages against the Israeli occupation, as well as Palestinian nationalism. The symbolic struggle inspired Arab protestors, many of whom grew up during the Second Intifada (2000-2005) and assimilated Palestinian means of protest as their own, an action that affirms the power of street art as a regional mode of expression and resistance (Karl and Zoghbi 2011: 100, 125, ctd. in LeVine 2015, 6).

It must be said that while street art may have been ubiquitous in the Arab Uprisings, it did not enjoy a uniformly enthusiastic tradition across the region before 2011. In some countries, like Tunisia, there existed little regard, or indeed tolerance, for street art as an expressive or political practice prior to the uprisings (LeVine 2015: 6). And in Syria, where the regime allowed for only small expressions of dissent prior to 2011, street art produced the gravest consequences. In the small town of Dara’a, teenagers spray-painted revolutionary slogans – which they had seen on TV, scrawled in Egyptian and Tunisian public spaces – on a high school wall: Freedom. Down with the Regime. Their arrest and mistreatment during more than a month of captivity set off protests across Dara’a. When they were released, the regime retaliated, shutting down internet access, and firing bullets in a square outside the Omari mosque. For many Syrians, these events marked the beginning of the country’s ongoing civil war.

Yet street art is still a quintessential revolutionary intervention, carving out space, marking time, chronicling sentiment and power. In Egypt, in many ways the most visible/visual site of the uprisings, protestors and regime actors engaged in sparring matches: street art went up, got covered up, and the cover-ups got covered up by new street art. The streets acted as newspapers, warning civilians of military and police presence; and as canvases for uplifting messages for the people. The most famous was the so-called Revolutionary Wall on Mohamed Mahmoud Street near Tahrir Square, where the art served up ongoing commentary on the revolution as it went on. In the years since the uprisings, the American University in Cairo, which owns the wall, has largely destroyed it in line with the city’s post-revolution beautification plans. An important archive of contemporary Egyptian culture, politics, and revolution has been erased, the wall scrubbed of the human voices and experiences made visual by Cairo’s artists. While a monument to the revolution has since been erected by the government, the state has been accused of trying to co-opt the revolution, stamping out not only street art, but a truthful urban narrative of the uprising as well.

Lebanon knows well this tug of war between expression and silence, beautification and politics. And to be sure, graffiti occupies a legal grey-area in Lebanon.

In 2012, Syrian-born artist Semaan Khawam was jailed and taken to court for a series of pieces he painted, including small stenciled soldiers carrying tiny green AK-47s. Merely representational, without speech bubbles or captions, they occupied their posts in various neighborhoods until the day plain clothes police officers noticed Khawam painting, and decided that whatever was being said, or not said, tested the bounds of decency.

Khawam’s supporters organized a ‘Day of Expression.’ They took his stencils out into Beirut, an army of artists-for-the-day, too many to efficiently arrest. They covered walls with Khawam’s soldiers, sprayed on pithy slogans, and positioned birds (a theme in his oil paintings) in upward arcs, as though aiming for the sky above and beyond the walls and their peeling archives of posters advertising nightclubs, mobile phone plans and political parties.

Fast-forward to 2015, the beginning of Lebanon’s (ongoing) waste crisis, which started when a major landfill shut down and the government had no contingency plan in place. Dumping trash onto sidewalks and into the ocean, and burning waste in the middle of the street became daily practice. The resulting health crisis prompted thousands to demonstrate downtown. As unrest grew, armed forces set up a barricade between the Grand Serail and the protestors. Locals involved in the secular, youth-fronted #YouStink movement asked Halwani to paint the wall.[2] When he saw protestors coming forward to add their own sentiments, in plain sight of police and the army, he backed off, making room for others’ self-expression in public space.

In October 2019, spurred by a host of persistent ills, protestors took to the streets again, in another display of cross-sectarian solidarity. The country was perpetually on the verge of economic collapse: it had maintained a debt-to-GDP ratio of above 150% for at least two decades, yet sustained yearly increases to government salaries. Wildfires were also ravaging the mountains: people and animals died in the flames, while fire-fighting helicopters sat, useless due to neglect, at Beirut’s airport. The country’s routine electricity cuts continued, but the government announced a new WhatsApp call tax to generate funds for Lebanon’s 2020 budget.

That was the final straw: a government clearly unconcerned about the welfare of its citizens would tax them for merely connecting with each other.

Word spread quickly via social media, and soon a small tent city blossomed in the no-man’s land along the old Green Line, which divided East and West Beirut during the civil war, and in many ways still traces out divisions in the city. Schools shut down, students took to the streets. As did their parents. And their grandparents. Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned 13 days into the revolution. People occupied buildings long closed to the public, like the Egg, a movie theater whose construction was interrupted during the civil war, and which stands as an unofficial monument to the conflict. Local organizations set up tents for teach-ins and talk-backs, where people could learn about the rights guaranteed (if not given) them by their constitution, and debate the issues facing the country. Protestors showed up in downtown Beirut not because they were ordered to by their respective sectarian leaders, but because of a pressing recognition that the ills of the state were the same ills experienced by each and every community in the country.

The public took back public space. And so the revolution began.

And so it continues.

I land in Beirut in early November 2019 to meet up with friends, family, and interlocutors who I know will be involved in some way in the revolution. The normally bustling highways leading into the city, often jammed at all hours, are strangely quiet as my cab speeds me into West Beirut. I catch sight of young men rolling tires out from under an overpass, directing them at the road, presumably to light them on fire, a preferred mode of protest in Lebanon. The cabbie pulls over to a group of soldiers and alerts them to the probable fires. All along the divider, I read ‘thawra, thawra thawra…’ (revolution).

On my first day back in the city, I walk to Martyrs’ Square, which has played host to countless protests, as much because of its central location between East and West Beirut as for its iconic statue, a tribute to Lebanese and Arab nationalists martyred at the order of Ottoman military ruler Jamal Pasha in 1916. The dusty patchwork of dirt lot and parking lot that normally surrounds Martyrs’ Square is covered in small tents. Narghileh smoke and Arabic deep house waft out from between their flaps, their inhabitants relaxing before the next protest. The huge Revolution Fist, visible in recent press photos, punches into the sky.

The camp and its surrounding streets are remarkably tidy. Activists stay mindful of their environment. Recycling bins, still relatively novel in Lebanon, have been set up. People pick up their trash and, if they pack up their tents, do not leave waste behind. They look after the streets in a way that has not been typical in Lebanon, the sort of ‘aesthetic ordering’ undertaken by Tahrir Square protestors nearly a decade ago in demonstrations of revolutionary care for their communal spaces (Winegar 2016).

I approach the statue at Martyrs’ Square and find a young woman busy painting its white base. She has covered the entire foundation in unexpected colors: purple butterflies, swirling pink waves, soft blues and yellows… There are no words, she has not painted ‘thawra’, and yet this indelibly feminine imagery feels brazenly revolutionary. A woman, open-mouthed and yelling out towards the city, takes up a full quarter of the piece, hair flowing from her face as though pushed back with the force of her declaration. The artist, Tamara, has been working in the square for several days, collaborating on parts of the painting with her friend Shadi. Originally from Syria, Tamara moved to Beirut two years ago and has been studying design at a local art school. “You’ve never seen anything like this before in Beirut, right?” she asks me. I admit I haven’t. “It’s always the guys painting. But the feminine is revolutionary.”

As we talk, a young boy comes by and tries to sell me a bottle of water. When I decline, he wedges himself in behind Tamara’s work table, and she offers him paint. He draws a Lebanese flag – stripes and cedars in pink, purple, and blue. His name is Khaled, but when I ask him where he is from, he looks away. “Poor thing,” Tamara says. “He probably doesn’t want to tell you because he’s undocumented and afraid he will get in trouble for trying to sell you water.”

Marginalized people, including refugees, do not have an obvious presence at the protests. Instead, like Khaled, they peddle bottles of water and sweets like ka’ak to protestors and organizers, moving through the crowds, trying to make money out of the nightly gatherings in the various squares in Beirut.

Solidarity has its limits, too.

Street art, however, has opened space for other voices. Local group Art of Change fires up its members to participate in one of the first women’s protests of the revolution. After a candlelight vigil attended by hundreds, during which they chant and sing songs appropriated from old patriarchal folk tunes, women set up a circle of candles, and in their light, artists paint on Martyrs’ Square while a crowd encircles them, watching, filming, photographing. Women’s faces take shape from spray paint and through brushes, gazing up from the asphalt, righteous Ophelias emerging in the glow, reminders of women’s increasing visibility in Lebanese civil society and political life.

And there amongst them is Khaled. One of the artists has given him several pieces of chalk, and he is deeply engaged in drawing. I say hello and ask him what he’s done. “It’s a boy and a girl,” he says. “They’re holding hands. And here is a bird, and some flowers.” The flowers, like the boy and girl, are smiling.

Activists organize demonstrations through social media platforms, through WhatsApp, and through word of mouth. Importantly, the revolution is leaderless, steered by the masses instead of a centralized command. The energy this generates is clear in the swirling soundscape of the city at night: dance music over loudspeakers, people banging on pots and pans while zipping through Beirut’s streets on motorbikes, chants from alleyways, megaphone-amplified voices cutting through the calls to prayer in the many pockets of the city.

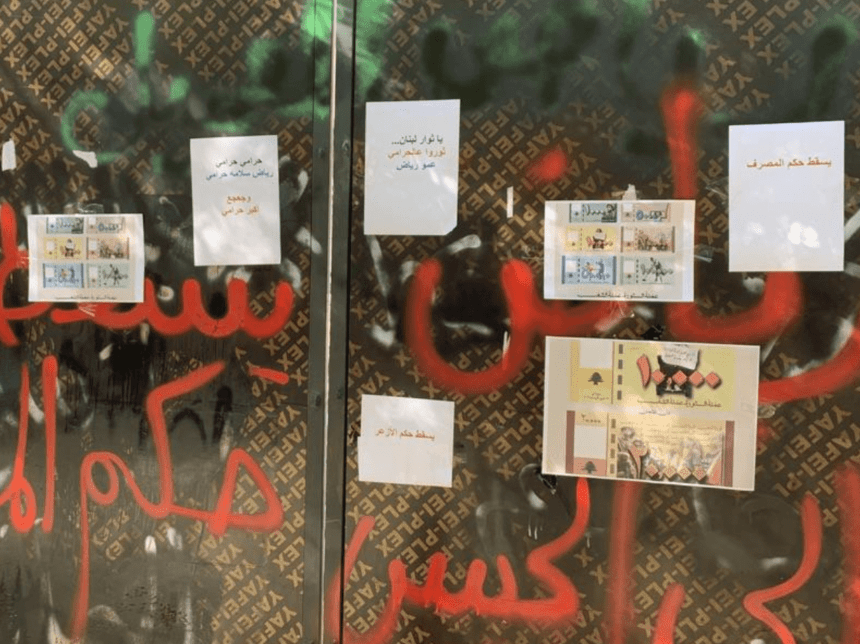

Site-specific graffiti has also emerged, addressing corruption in the telecommunication and banking industries. One night I come across a small band of fifteen or so protestors. While a woman plays rhythms on a tabla drum, two men take turns chanting call-and-response style into a small megaphone. The crowd – several children among them – laugh at the irreverence of the lyrics, which take the government and the banks to task for devaluing the Lebanese lira vis à vis the US dollar (also accepted currency in Lebanon). Pages printed with images of Lebanon’s colorful bills are glued to this barricade, along with salty slogans criticizing the banks and lawmakers for the inflation that is causing the country’s economic emergency.

Soldiers stand with their hands on their Kalashnikovs, against a wall erected to protect the national bank.

The soldiers have perhaps been sent to help avoid the fate of other banks. I visit a Bank Audi branch on a Thursday, to see my friend Elie who works there. He takes a break to chat outside. The banks have just re-opened after closing for several days due to unrest. Elie’s manager is trying to calm long-term customers, who are panicking and trying to withdraw all their funds while the banks stay open.

As I wind my way back down to the city center, I stop to photograph the Fuad Chehab Bridge, which funnels traffic between East and West Beirut. Physh, a street artist I’d met years ago, says that his friends have been active in that area, and indeed the concrete wall is alive with revolution. These veins between neighborhoods carry the slogans and emotions that connect, however ephemerally, the city’s sectarian geography, re-membering the shared history and legacy of suffering at the hands of the most powerful (Cory 2015).

Around the corner from the bank, I find a message scrawled in green paint: No era depresión, era capitalismo, from Beirut to Santiago. ‘It wasn’t depression, it was capitalism.’ Solidarity isn’t just local, or national, or even regional. Chilean protestors, set off by similar developments like hikes in metro fares and rampant privatization – the latest in a long list of injustices – have apparently found their way to a wall in Beirut, or have had a proxy write a message of solidarity for them.

Further on, offices belonging to banks and other arbiters of capitalismo are marked with the more aggressive signs of revolution: broken windows lie splintered on the pavement, the sites of impact portholes into abandoned rooms littered with graffiti.

Thawra, thawra. On the walls outside, cheeky stencils of politicians’ silhouettes sit along damning slogans, well-placed, thought through: Kiss Imou (His mother’s cunt), YES ALL POLITICIANS, Sex is good but have you ever fucked the system?

A notice declares that this branch of BankMed is closed until further notice.

In the couple of months after I left Beirut, the streets turned up the volume. Activists organized clothing drives for those protesting and those caught in Lebanon’s poverty cycle. More tents served free food for those demonstrating in downtown Beirut. Teach-ins multiplied. Students burned textbooks in front of the Ministry of Education to challenge school closings and a curriculum that does not teach them their own history or geography. Activists from Tripoli bussed down to Beirut in solidarity, and Beirutis went north to Tripoli as well. The day-to-day actions were myriad and persistent. Grassroots media organizations like Megaphone News went live at demonstrations and archived online the actions of the state. Protests still ran day and night. The same clear voice echoed between neighborhoods, suturing together the fabric of a city long divided: Kiloun ya3nee Kiloun (All of them means all of them). It was time to dismantle the sectarian government, formed during the French Mandate and run by civil war-era warlords since the early 1990s, and to push for an end to widespread corruption across all sectarian lines.

And yet…

Security forces blasted crowds with tear gas and rubber bullets. Banks imposed capital controls, barring customers from withdrawing more than 200 USD every 15 days. Prices of food and consumer goods continued to rise, by up to 40%. The army erected the Wall of Shame, a structure made of concrete and metal barricades, to keep protestors away from Parliament. Inclement weather at times produced flash floods that washed away encampments and donation sites. And when the streets were once again dry, these same structures were subject to looting and attacks by counter-protestors.

In December, Minister of Education Hassan Diab was elected as Lebanon’s new prime minister. Despite protestors’ demands, a new government was agreed upon in January 2020, and in February were officially voted in. While Diab was relatively low-profile before his appointment, he has the support of the pro-Syrian March 8 Alliance, which leaves many sectarian leaders comfortably in place. Nevertheless, Diab set up his new Cabinet, made up of 20 so-called ‘technocrats’ as members, and vowed to reform Lebanon’s electoral law.[3] If he pursues reform, the sectarian nature of Lebanese politics (which also informs the inequalities in the country) could be challenged.

Activists, however, remain unconvinced and have repeatedly expressed no confidence in Diab and the larger government, as their country hurtles toward economic collapse by way of a bond default.

They continue to show up downtown, as near to Parliament as they can get given the circumstances, and to protest in Martyrs’ Square as generations of Lebanese have done before them. The Revolution Fist met its end in November, consumed by flamed on Independence Day. A phoenix, constructed by Lebanese artist Hayat Nazer from the metal poles of tents destroyed by counter-protestors, rose in its place. On Valentine’s Day, Nazer revealed her latest work: a huge heart composed of tear gas canisters, rocks, and barbed wire, meant to represent the unity of the Lebanese people, whichever side of the conflict – revolutionaries or establishment – they are currently on. The heart’s support bears the names of Lebanese who have lost their lives challenging the status quo, including journalists, and activists in the current revolution. When it is lit up at night, its neon lights throw a heart-shaped shadow upon the Wall of Shame, illuminating both the challenges of the present and, perhaps, the way forward.

Epilogue

I wrote this piece in the early days of 2020, well in advance of the upheavals (some new, some old but revitalized by growing awareness of persistent global injustices) that will surely make this year infamous.

A worsening economy has meant fluctuating exchange rates, with the Lebanese lira depreciating to a rate of 7,000 lira to 1 USD on June 11th, up from the standard 1,507.5 lira. The country has a debt of more than 170% of its GDP and defaulted in March. While the lockdown imposed by the government since March in response to the Covid-19 pandemic may have dampened protests for a time, June saw easing restrictions and thus a return to the streets.

Demonstrators have even more to fuel the flames of protest now: unemployment is up to 35%, the tourism industry is down, and vast swaths of the population are dealing with food insecurity. Reports have emerged of daytime robberies by tearful people who apologize on-site for stealing – their families are starving, there is nothing else to do. Lebanese are facing the worst economic crisis since the civil war, and while the precariousness of the situation encourages solidarity, the Internal Security Forces (ISF) have clashed with demonstrators, and ISF has detained at least 100 activists since the revolution began.[4]

And then, on August 4th, a blast located in Beirut’s port, and felt as far away as Cyprus, ripped through surrounding neighborhoods, decimating the city to a degree not seen since the civil war. Many of my friends took to social media, uploading videos of the explosion and its aftermath – bloodied civilians, streets seemingly cobbled in broken glass – as speculation swirled around what had happened. Was it an Israeli attack on Hezbollah weapons stores? Was it a warning ahead of the verdict, due August 7th in the Hague, for Hezbollah members linked to the 2005 murder of ex-PM Rafik Hariri?

It seems not. Although information is still emerging, the blast apparently resulted from 2,700 tons of toxic ammonia nitrate that the government had stored in warehouses at the port, which sits just a couple of hundred meters from residential areas. If this is in fact what happened, it is a devastating revelation, an excruciating example of adding insult to injury: instead of having outside parties to blame for an attack, Lebanese must contend with the latest in a long history of terrorist (in)actions on the part of a government willing to sacrifice its people’s basic safety for the sake of convenience, power, and a neoliberal development agenda.

The sit-ins and dance parties feel long ago indeed in the face of mounting desperation. Lebanese politics has never lent itself to neat conclusions. Modes of dissent and solidarity, too, quickly change in color and scope in Lebanon, depending on what the moment calls for. We might expect the revolution – and the protests that carry it – to continue in some form, even if only, for the moment, online. As I write this, on August 5th, social media is filled with potent rage. Kiloun ya3nee Kiloun, the charge of last October’s uprisings, circulates anew. But there is grief, deep grief, too. A friend writes to me: “Habibte, everything we know is gone. I don’t know how to breathe anymore.”

Dr. Erin E. Cory is Senior Lecturer in Media & Communication Studies at Malmö University, Sweden. Before moving to Scandinavia, Erin lived and worked in the U.S. and in Lebanon, where she conducted fieldwork towards her dissertation (UC San Diego, 2015). Her current research, supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, examines the role of participatory art in building everyday solidarities between new arrivals and autochthonous Swedes.

Notes:

[1] Anonymous street artist in conversation with the author, April 2013.

[2] The #YouStink movement has its roots in the grassroots organization of the same name, which led protests against the Lebanese government during the summer of 2015. Protestors both used funny slogans, and harnessed the protest rhetoric of the Arab Uprisings. These protests encouraged the formation of the volunteer-led political campaign Beirut Madinati (Beirut, My City).

[3] For a list of the cabinet members, please see: https://en.annahar.com/article/1109464-lebanons-cabinet-lineup-who-are-our-ministers.

[4] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/lebanon-detained-100-activists-october-200622091557209.html.

References

Cory, Erin Elizabeth. 2015. Re-Membering Beirut: Performing Memory and Community Across a “Postwar” City. http://search.proquest.com/docview/1753896474.

LeVine, Mark. 2015. “When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World.” Religions. 6 (4): 1277-1313.

Maasri, Zeina. 2009. Off the Wall: Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War. London: I.B. Taurus.

Winegar, Jessica. 2016. “A civilized revolution: Aesthetics and political action in Egypt.” American Ethnologist. 43 (4): 609-622.