Transcription: Lauren Bon Presentation with Newton Harrison

Lauren Bon & Newton Harrison

Lauren Bon: Listening to the Web of Life

Thank you Tatiana for this beautiful name.

Listen.

If you listen here, if you listen here on this site. (That’s my screen saver – my virtual background.) You’ll hear birds

And you’ll hear trains and you’ll hear cars and you’ll often hear desperation of the unhoused community that lives in the infrastructure corridor of the LA River and other infrastructure corridors in the arid lands of the greater West.

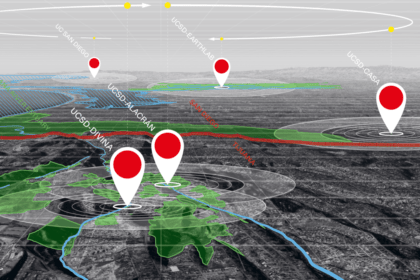

Bending the river is an infrastructural artwork. It aims to redirect that low flow channel that you see in this image.

The “low flow channel” that even after months and months of no rain has water in it from all of the things that we use municipal water for cleaning our roads, cleaning our yards, and watering our lawns.

It all flows out to sea. Bending the river asks the question

“Wouldn’t it be good if instead we could redirect just a small portion of the low flow channel of this river?”

Lift it on the power of the water’s movement itself?

Move it through a native wetland on this site here – the one that you see the triangles on which are actually triangles lifted out of the river – before reconnecting to its floodplain, currently the Los Angeles Historic Park – that I spent a large part of my practice cultivating.

In 2005, I was able to clean it up with a performative action of growing corn on all 32 acres of brown field.

And that catalyzed the park into being.

When I did “Not a Cornfield” – I would go down to the river here with a red truck and fill it up with water and then I found out that that wasn’t permitted and I couldn’t understand why.

Why would it be that water, that would normally just go out to sea, couldn’t be used to clean up the park?

Bending the river is about thinking about this kind of common sense and the 69 local, state and federal permits that I’ve had to get in order to be in construction with this project — it shouldn’t be that difficult.

I had no idea that doing something that seemed so logical – taking water that is a waste product and connecting it to land that desperately needs to be re-energized, re-generated would be such a difficult thing to do.

But it is and it makes one think as an environmental artist that maybe part of our job is to persevere through these permitting processes, in order to create new stories and new cultures of care.

I’m so glad that we were finally able to get into the river because it was only by lifting these triangles that you see behind my head that we discovered a river underneath the river.

That not the treated wastewater but the water itself is flowing under this large area of concrete that we call a river but is actually flood control measures.

But underneath that river is another river and that river has a floodplain there?

And that floodplain is a miraculous Organism. It’s capable of sequestering carbon and giving off oxygen as if it were an old growth forest. Let me show you.

This cut that you see here. It’s a cut created by the removal of those triangles.

Isn’t it beautiful? Imagine my surprise when lifting those triangles in that brutal environment. What I found was this pure water. So what you’re seeing here is this red line and the yellow box is Metabolic Studio. That’s my studio building that you saw as my virtual background. Right here.

And this is the way that the watershed once looked. The red dot is where this water is and this red dot shows all of the natural rivers and streams that flow from the mountains. That would have regularly flooded this whole basin here. So this whole basin, this Los Angeles water basin would have been an incredibly fertile zone, carrying food – medicine – for the pre-colonial people who lived here as well as the animals and the fish.

That would have made this place abundant.

So I’ll show you a little bit of video about this project.

Thank you so much for allowing me to contribute to this conference.

Thank you for allowing me to share this public work with you.

Newton Harrison: “You know what?”

Lauren Bon: “What?”

Newton: Around 1987 I found a map of the whole LA Basin River system, and 90% of it was in concrete. In the book, I think I have that map. And I’d like you to refer to it because it invisibly tells the shocking story.

Lauren: Is it connected to your Hahumunga project?

Newton: Yes

Lauren: Yeah, I know that Map.

Newton: OK it’s grayish and well, I suggest that that map – I know by now it’s like 25 – 30 years old by that, but an improved version, a high drama version of that map needs to be there, and now there’s another calculation. Can’t believe I’m doing this, another calculation that might be good to make. You’ve just lifted up like a 20 by 50 area of concrete or something like that, right?

Lauren: It’s 77 feet by 300 feet.

Newton: That’s a big piece yeah. But this is one thousandth of 1% of the amount of concrete on our rivers. And the power of this thing is if you can if you take the map I have and make a more powerful or grown up version – since it’s 30 years old – and then those diamonds – You have the possibility – not the possibility by now it’s the obligation – to make a narrative that people can get and the narrative is a word image, thing. That’s stuff Helen and I struggle with all those years.

But here’s what strikes me, if I see that map and then i see, then I shrink down to your section of river, then I see the 300 feet lifted up. Then I see the concrete thing. And then I say there are several million of these Mack trucks of concrete that make our rivers that tells you a story of culture that has to change.

Lauren: So, this is this red dot here on the right. Is the picture of where this is taken right? So your map was clearly articulating this line. All of the water that moves from the Arroyo Seco down to this point. It would have been joined then with the water coming from the artificial watershed here. So this point where the Arroyo Seco meets at this point is an incredibly invisible bread basket, right? Like I don’t think that there’s a way to clearly articulate the power in an arid land of this location.

Newton: OK, let me make this second suggestion. Umm? It posed the question of can you interface a complex, but unpredictable, new kind of ecology that we’re talking about in several hundred places in the LA Basin where you find the places to rehab them?

And the proposal then is to set up the conditions for a novel floodplain ecosystem to emerge that will not be the floodplain, but it will be the whisper of what it was and the direction it’ll have to take because ultimately people will move out and these concrete things will overflow, and all kinds of stuff will happen.

Lauren: And also there’s the other thing which is that we have less rain, but when we have rain, we have more of it and we can’t recharge the water table with everything sealed.

Newton: It’s certainly true.

Lauren: So it’s also that added complexity of needing to resource the water.

Lauren Bon: Newton and Helen have been instrumental in helping me understand what this work is a part of, namely the hydraulic water and power grid of the greater West. And advocating for this being a drop in the bucket. But a realizable, scalable drop.