Images of Protest: Hong Kong 2019-2020

Mai Corlin Frederiksen

The protests in Hong Kong the summer and fall of 2019, (re)ignited when the administration of Hong Kong, headed by chief executive Carrie Lam, proposed an extradition agreement that would allow China, amongst other nations, to extradite suspects for prosecution. [1] The fear in the general population in Hong Kong was that this would allow the Chinese state to prosecute political dissidents that had so far felt relatively safe in Hong Kong. The demonstrations and mass rallies grew in strength beginning in June 2019 and culminated with the weeklong intense and violent siege of Hong Kong Polytechnic University in November 2019. The protests faded out with the advent of the coronavirus outbreak in February 2020 and was given the final death blow with the introduction of the new national security legislation in June 2020.

European and North American media outlets have primarily shown the protests in Hong Kong through the weekly demonstrations, violent clashes with the police and the large-scale mass rallies. However, people living in Hong Kong during the protests will most certainly also have noticed the massive amounts of visual protest material present on the more than 150 protest walls scattered across the territory. Every footbridge, underpass, metro station, tunnel system or available wall in Hong Kong was turned into a hotspot for distribution of visual protest material – and the material on these walls was renewed on a daily basis reflecting events on the streets and on the political arena. Visual protest material, online as well as in physical space, played a crucial role for the movement, in the formation of their political imaginary of a Hong Kong free of Chinese influence, and as means to affect the public opinion.

The protest movement’s use of visual material to territorialize Hong Kong proved significant in the ability of the movement to secure public support. The movement was so successful in controlling the narrative, that even though the proposed extradition bill was withdrawn by CE Carrie Lam, the protests and the importance placed on constantly renewing the material on the protest walls continued with unforeseen strength. [2] If anything, the withdrawal showed that their efforts proved effective.

Below, I will give an analysis of examples of some of the visual material found on the walls, examples that depict a narrative of a free Hong Kong composed of a community of protesters of all ages and all walks of life. The production of visual material was coordinated by the so-called “Publicity Group” (文宣), which consisted of a large group of anonymous image producers (200-500 people) deliberating over and creating visual material for the protests walls. The material is shared on digital platforms, of which Telegram and LIHKG are the preferred ones for sharing of image files. Other groups of people and individuals then print and glue the posters on the walls independent of the Publicity Group. The Publicity Group uses different methods to produce the visual protest material, of which I will go through a few here.

Recuperation

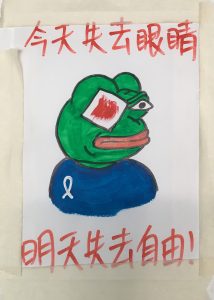

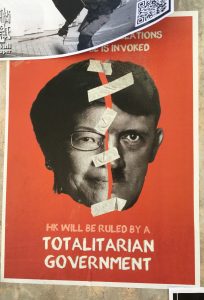

An often-used method of the Publicity Group is what we could call a recuperation of symbols, that is they take an existing symbol and give it a new meaning in service of their purpose. In fig. 1, we see Pepe the Frog who was originally recuperated by right wing supporters of President Trump for his presidential election campaign, but who has now been hi-jacked to be an avid supporter of the Hong Kong protests. Fig. 2 shows the Chinese character Mei from the company Blizzard’s game “Overwatch.” Blizzard punished some of their gamers for openly supporting the protesters in Hong Kong, in return the protesters made Blizzard’s character into a supporter. Also, we have the well-known game of Monopoly now referring to the police, known in Hong Kong as the “popo,” and their government-granted monopoly on violence (fig. 3). And CE Carrie Lam seems to morph into Hitler (fig. 4). Hitler and the notion of Nazis are often used as a proxy for referring to an authoritarian regime. Here, recuperation is used as a shortcut to people’s attention as they present something recognizable, but with new meaning.

Infographics

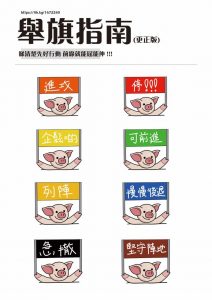

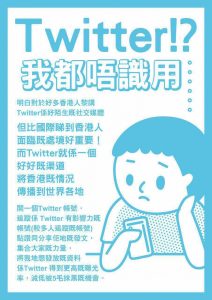

Another category of protest material is that of infographics. Infographics seek to provide the public with various types of information. Some of the infographics provide information of historic and current examples of suppression of the Chinese state – an approach that can be tied directly to the understanding of the communist party and the government as concealing information. Other examples of infographics are more directly linked to the day-to-day battle in Hong Kong and are aimed at providing protesters and other sympathizers with information on how to behave in certain situations.

Figures 5-8 show some examples of infographics. The first one tells you how to act during demonstration when a certain color flag is raised (fig. 5). The second one tells you how to act and what NOT to wear on election day: November 24th 2019, as opposed to what you should usually wear during demonstrations (fig. 6). The poster instructs you to arrive early and make sure that everything is in order with the ballot. Furthermore, you should remember to blow on the ink before you hand over the ballot, to make sure the ink is dry and thus cannot be changed. Other infographics will instruct you who not to vote for. The third one, tells you which press services are reliable (e.g. not affiliated with Mainland China) (fig. 7) by drawing a very clear line. Similarly, there have been infographics depicting which shops are yellow (e.g. pro-movement) and which shops are deemed blue (e.g. pro-government), and how you should refrain from frequenting blue shops and cafes. The last one is a guide to the use of Twitter in spreading the message of what is going on in Hong Kong (fig. 8), an important tactic for pan-democratic supporters of the movement. This is just a really small sample of infographics, to give an idea of the scope. Infographics are used to a great extent as method to counter the narrative and attempts of the government to conceal information. Furthermore, the Publicity Group use infographics to visualize how you should act as a supporter of the movement and thus provides the movement with a code of conduct.

Events to graphic

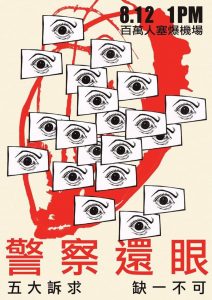

Another predominant method to produce content for the walls is to look towards events on the streets during demonstrations and use that information to produce content and symbols to be used in the battle of the public opinion. The examples given below were all found on Telegram, however, many of these were also printed and hung as posters in public space and on the protest walls across Hong Kong.

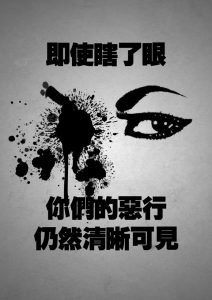

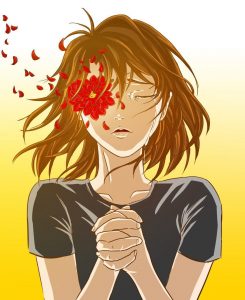

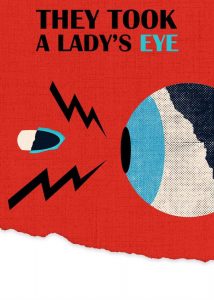

On August 11, a female nurse and protester on the backlines, got shot in the eye with a beanbag round by the police. As usual, in the hours and days after the incident, a surge of graphic content was produced. The visual reproduction of the female with her one eye shot quickly became an ideal symbol for the movement as it came to represent the police violence and power abuse the movement suffered. This event with the depiction of the female with her eye shot is a good example of how the process of production of content unfolded. Fig. 9-12 shows how the Publicity Group reproduces of the image of the woman over and over again and multiply the visual output by presenting different versions of the same. There are cartoonish-versions, pepe-the-frog versions, hand-painted versions, fact-sheet versions, water-color versions, dramatic versions, soft versions and so forth, all catering to different people and different segments of society. Nevertheless, the young woman is primarily presented as a girlish, innocent protester shot directly in the face for no good reason.

The eye as a symbol of police violence was already there for the taking, as it had been used as part of the visual protest repertoire prior to the incident with the woman. It had been used to refer to the all seeing eye of “big brother,” the idea of the surveillance state connected to China and when referring to events and incidents, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was understood to conceal. It was a convenient proxy for the notion that the protest movement “saw through” the propaganda and secrecy of the CCP. The reinvigoration of the “eye” with this new symbolism connected directly to events during the protests in Hong Kong only made the symbol stronger. It was afterwards repeated again and again in various types of protest posters throughout the protest period.

The protesters

As with the young woman, I just described, the representation of the protesters as innocent, loving and vulnerable recur in many of the depictions of the protesters. Like in this collection of posters:

The protesters are more often than not depicted as vulnerable, compassionate and peaceful protesters against an all-powerful supremist. They fight with non-lethal, everyday objects such as umbrellas, traffic cones, tennis rackets and gas masks and they help each other should anyone get hurt in the violent clashes with the police (fig. 15). Furthermore, a group of protest posters are specifically concerned with the mental well-being of the protesters, such as this example:

Do Not Split

Another very strong trope present in the visual material is the idea of opposing views fighting the battle together, thus placing significant importance on not splitting and disintegrating into disagreement. In all its diversity, the movement included positions ranging from democrats, anarchists, anti-capitalist as well as nationalists and localists, or as they were divided in Hong Kong at the time: as wo lei fei fei (peaceful, rational, non-violent) protesters and yong mo (valiance) protesters.

As early as mid June, 2019 a poster showed a protester dressed in the frontline uniform (yong mo) hand in hand with a protester without all the frontline gear (wo lei fei fei), the poster reads: all factions should cooperate, unite and do not split (fig. 17). This poster, and many other like it, communicate to movement participants how to react to differences of opinion and the importance of standing together united. As a mantra, do not split, is repeated again and again, and as such serves several purposes: instructing people within the movement how to act at the same time as it displays this unity to a broader public.

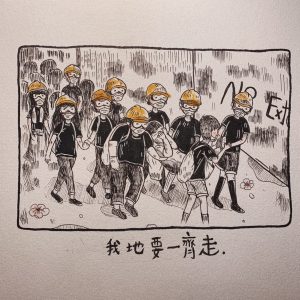

To begin with the unity within the movement is mostly represented by the two figures of the peaceful and the valiant protester, later, however and entire community of protesters become included in the unity, as this poster shows:

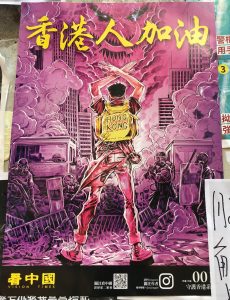

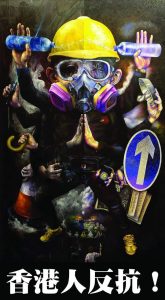

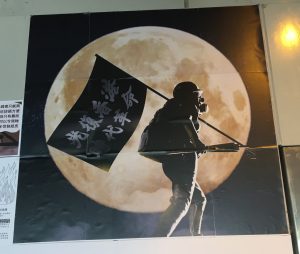

Nevertheless, one of the central and most reproduced images of the protest movement is the image of the black-dressed protester wearing a safety helmet, a gas mask and carrying a flag or an umbrella in their hand (fig. 19 and 20).

The black clothes refer to the uniform that frontline protesters are wearing during the weekly demonstration, in order to better be able to hide from the police in the dark corners of the city. But in addition to being the required uniform of the front runners, the protesters on the backlines have adopted the uniform in an act to protect the front liners. The logic is, that if everyone is wearing black clothes and safety helmets, the police won’t be able to discern one protester from another, in a sense creating a uniform of anonymity. Fig. 21 not only shows the protesters as against an authoritarian superpower, it shows the protester in the middle of the act of territorializing. He/she is seemingly conquering the moon, claiming territory and winning an impossible battle.

Concluding remarks

In this short visual essay, I have laid out some of the tropes that were visible within the Hong Kong protest movement from 2019-2020. The amount of visual material produced during this period was massive, and I do not purport to be familiar with all corners of the visual resistance of the protest movement. However, these examples do show some overall tendencies in the production of images as central to the formation of a political identity as protester in Hong Kong, such as unity, compassion, power and information. The visual material tells you what to think and feel and how to act in relations to the ongoing conflict in Hong Kong. It literally depicts the possibility of an independent Hong Kong through a highly visual territorialization of the territory of Hong Kong.

With the introduction of the national security legislation on June 30th, 2020, however, the circumstances for producing and safely distributing visual protest material changed greatly. Overnight, supporters of the protest movement across Hong Kong removed protest posters, post-it notes, flags and other visual protest material. Collections of protest material were sent abroad, books were removed from the shelves of bookstores, and private protest walls in shops and cafes across town were dismantled. Suddenly, it became very obvious what could no longer be said and shown. The disappearance was what made it all so obvious. The same tactic of disappearance was now used in much of the protest material. Blank papers were raised in the LegCo, to illustrate what they could no longer say. The protest movement in Hong Kong had to change their methods all together. The coming years will show how this legislation becomes embedded in Hong Kong society and how it effects the production of protest material in the longer run.

Mai Corlin Frederiksen is currently Carlsberg Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Copenhagen, working on a research project on the image politics of the 2019 protest movement in Hong Kong. She has previously done extensive research into socially engaged art practices in China and Hong Kong. She is the author of The Bishan Commune and the Practice of Socially Engaged Art in Rural China (Palgrave, 2020) and “Aesthetics of Reciprocity: Socially Engaged Art in China and Hong Kong” in The Routledge Companion to Art and Activism in the Twenty-First Century (Routledge, forthcoming).

Notes

1. All the images in this article are either taken by me in Hong Kong during the summer and fall of 2019 or collected via public groups on the messaging app Telegram during that same period. I would like to express my gratitude to Frank Vigneron, professor of art history at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, for bringing me to Hong Kong as postdoctoral researcher in the first place. I arrived in Hong Kong five days before the storming of the LegCo July 1st, 2019 and I left Hong Kong way too early in February 2020 due to the coronavirus situation. Thanks also to the Carlsberg Foundation for generously funding further research into the visual aspects of the Hong Kong protest movement after I returned to Denmark.

2. For more reading on the protest movement in Hong Kong, I can recommend the writings published by anarchist/left-wing collectives such as Lausan, Crimethinc and Chuang. They are some of the few outlets that have also presented a critique of the more nationalistic and racist sentiments of the Hong Kong protest movement, see Zhao 2020, Crimethinc 2019, Wong 2020. Other relevant and important articles on the movement includes Lee et al. (2019) and Lee (2020), articles that shed light on the composition of the movement and on the solidarity between the different radical wings of the movement (Lee 2020). Lee et al. (2019) provides data that supports claims to a leaderless movement, such as how a majority of the movement participants are self-mobilized and the documented “antipathy among the protesters towards a centralized movement leadership” (Lee et al. 2019: 14-15).

Literature

Chuang. 2019. ”Other Voices from the Anti-Extradition Movement,” Chuang. http://chuangcn.org/2019/06/anti-extradition-translations/

Crimethinc. 2019. “Anarchists in the Resistance to the Extradition Bill,” Crimethinc. https://da.crimethinc.com/2019/06/22/hong-kong-anarchists-in-the-resistance-to-the-extradition-bill-an-interview

Lee, Francis L. F., Samson Yuen, Gary Tang, and Edmund W. Cheng. 2019. “Hong Kong’s Summer of Uprising: From Anti-Extradition to Anti- Authoritarian Protests,” China Review 19 (4): 1-32.

Lee, Francis. 2020. “Solidarity in the Anti-Extradition Bill movement in Hong Kong,” Critical Asian Studies 52 (1): 18-32.

Wong, Ahkok Chun-Kwok. 2020. “On racial hatred: How the coronavirus has uncovered the dark side of Hong Kong’s movement.” Lausan. https://lausan.hk/2020/on-racial-hatred-how-the-coronavirus-has-uncovered-the-dark-side-of-hong-kongs-movement/

Zhao, Zoe. 2020. “Facing down the Hong Kong protests’ right wing turn.” Lausan. https://lausan.hk/2020/facing-down-the-hong-kong-protests-right-wing-turn/.