Encouraging Encounters: Dignicraft in Conversation with Ionit Behar

Dignicraft is a hybrid between an art collective, a media production company, and a distributor of cultural goods, inspired by human dignity and justice, the artisanal process of creation, and the potential of collaboration to spark change. The essence of the collective’s art practice is to encourage encounters normally not seen between people of different backgrounds. The group accomplishes this by producing documentaries, distributing cultural goods such as films, or creating collaborative workshops as part of a contemporary art project. The most important outcome for Dignicraft is the quality of the relationships they establish and their consequences. Dignicraft has been active since 2013 mainly in Tijuana, Mexico, and also transnationally in California, USA. The group was born of the evolution of the collective work that was started in 2000 under the name Bulbo and Galatea audio/visual. Currently, Dignicraft includes Paola Rodríguez, José Luis Figueroa, Omar Foglio, Blanca O. España †, David Figueroa, and Araceli Blancarte.

Ionit Behar: Often, your projects begin from a specific place and problem. Take, for instance, one of your early projects, Tijuaneados Anónimos (2009), a feature-length film about Tijuana and a group of citizens who participated in a workshop you designed. The documentary includes the testimonies of workshop participants, who share their experiences of the unprecedented wave of violence that erupted in Tijuana and throughout Mexico in 2006. I’m interested in the way your projects are local but also convey larger ideas and raise global questions. Perhaps what I’m trying to say is that your work demands sincerity and, above all, empathy. The idea of “empathy” in socially engaged art has become central to its criticism, both in positive and negative ways. Grant Kester writes that “it’s necessary to begin again to understand the nature of the political through a practical return to the most basic relationships and questions; of self to other, of individual to collective, of autonomy and solidarity, and conflict and consensus, against the grain of a now dominant neo-liberal capitalism and in the absence of the reassuring teleologies of past revolutionary movements.”[1] Is this something you think about when planning a project or getting involved with a new situation? Would you say your projects are as much about the people you meet as they are about yourself?

José Luis Figueroa: Our work takes place in daily life via personal interactions. We believe macro-level problems are experienced in the day-to-day. You might approach a situation theoretically to better understand it, but on the ground level, you live through it. The essence of our artistic or cultural practice is to encourage encounters normally not seen between people of different backgrounds. These encounters are fostered by collaboration, as a means to create a common ground where communication, understanding, exchange, and learning can be possible. We try to co-create possibilities for interaction between individuals or groups that can evolve into close collaborative relationships based on mutual recognition of value and respect, which are key ingredients for empathy. So instead of planning to achieve empathy, we try to avoid any preconceptions and approach other people, places, or situations to learn about them, paying attention along the way to see if there is any way we can be of help. The best way to do this is to let actions speak for themselves. Speak less in favor of doing things together.

IB: As a collective living in Tijuana, what is it like to live and work there. A lot of your work is site-specific––based on research, fieldwork, and relationships that you developed in different places where your projects take place. I wonder, how do your experiences in Tijuana inform your projects in different locations?

Omar Foglio: We are currently developing a space for residencies and knowledge exchange named “Basalto” just outside of Mexico City, in the town of Santa Catarina Ayotzingo, State of Mexico. At first, we thought the place had little to do with our hometown of Tijuana. However, the more time we spend down there working with people from the community, the more we realize that the Valley of Mexico has a dynamic with a strong resemblance to that of the region between Tijuana and Southern California, where life is marked by the border situation. But in this case, the division is between the State of Mexico and the City of Mexico, where there is also unequal access to resources and opportunities, three to four hour-long commutes, and this sensation of an immense periphery subordinated to a political, economic, and cultural center. In this sense, our experience on the border between Mexico and the US has been useful in engaging and understanding a place located almost two thousand miles from our home.

JLF: In our case, life in Tijuana has been binational and bicultural. This forces us to constantly change perspectives between different value systems, ways of thinking, and even working rhythms. This ability to move between cultures has been like a training that has prepared us for all the projects we do outside the city. Especially with the collaborative work we have done with families from the Purepecha communities in Mexico and the United States.

OF: Looking back, our practice has also changed in response to what the city has gone through. When we started Bulbo [2] in the early 2000s as a television program, we knew that we weren’t represented in broadcast media. The majority of the content that was sent to us was either from the United States or from Mexico City, so there was no place to see ourselves, our city, our generation, and the people around us. Consider that this is long before social media platforms evolved into what they are today, so it was even harder to create something and intervene in traditional broadcast media. So, first, the kind of issues we talked about had to do with our daily lives and people who were doing artistic, creative, and independent projects. At the moment, all of this coincided with what we were seeing in the city––there were lots of things happening, it was an exciting time.[3] But around 2006, and especially 2008, things in Tijuana started to change––violence having to do with the drug cartels started to get out of control, so there were a lot of kidnappings and everything went downhill. It felt like the city went into an extended period of depression, and it didn’t feel right to keep celebrating things or pretending that nothing was happening. So we knew we had to do something with our own means to address the situation, and that’s when we started working on projects like Participación [4] and Tijuaneados Anónimos.[5]

IB: Certain aspects of your work remind me of the art in Argentina in the 1960s and 1970s, during the dictatorship. I’m especially thinking about Arte de los medios de comunicación de masas (art of the mass media), which was an experimental arts group formed by Eduardo Costa, Roberto Jacoby, and Raúl Escari in 1966. They used mass media as their art form in order to question issues around truth and the power of media in society. Another important example is Tucumán Arde (Tucumán is Burning). Tucumán, a province in the northwest of Argentina, was extremely affected by the dictatorship; people were driven into poverty and starvation after the closing of several sugar mills and farms. Artists from Rosario and Buenos Aires created a counter-information movement, intervening in mass communication to reveal the regime’s lies about the situation in Tucumán. Artists were seeking to show the truth. I think that your documentary, Tijuaneados Anónimos, has to do in part with uncovering the truth. Can you please tell me a bit about how this project came about? The main component of the project is the documentary, but there are other elements that also form part of Tijuaneados Anónimos, right? Please tell me about those as well.

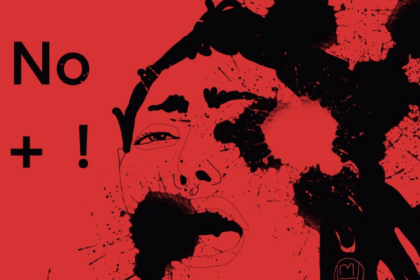

JLF: The city changed. We were seeing a lot of violent events, finding dead bodies hanging from a bridge and terrible things that were impacting the lives of everyone. But not only that. Tijuana, because of its geographical location, is a point of enormous flux; people, goods, and culture come and go through the border, but also drugs, arms, money, anything that comes to mind. We felt the city was a chaotic place and thought it would be nice to have some type of self-help program where people could deal with the situation happening in Tijuana at the time. Then building on the Alcoholics Anonymous “AA” logo, we created a graphic for an imaginary fellowship named “Tijuaneados Anónimos.” The plan was to make “TA” stickers, posters, pins, and distribute them throughout the city as the ironic gesture of an art project. The idea evolved into having an actual space open to the public, where a group of people would hold therapeutic sessions under the name of “Tijuaneados Anónimos.”

OF: It was hard for us to deal with the situation in the city and know how to talk about it. The actual space for Tijuaneados Anónimos was located in downtown Tijuana and was open to anyone who walked in and wanted to take part in the conversations. That lasted for about a year. Along the way, we recreated the “TA” space as part of the “Inside the Wave: Six San Diego / Tijuana Artists Construct Social Art” exhibition at the San Diego Museum of Art, and created an installation at the 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica for “The Future of Nations – Part III: Citizen Artists Making Emphatic Arguments” exhibit, incorporating video clips of the sessions and the logo sign. But after a few months the group took on a life of its own; we listened to the stories that were going on inside, and we felt the need to take this conversation further. That’s when we started to work on a documentary film [6] focusing on some of the people that were part of the “12-step program.”

JLF: The documentary opened the opportunity for us to travel throughout Mexico as part of the Ambulante Film Festival, stopping by the country’s major cities. The film inspired people to reflect upon the problems they were facing in their own cities. We then realized that the situation in Tijuana, in terms of violence, was a few steps ahead of what was starting to happen all over Mexico. A strong sign of this was the need of audience members to talk during the Q&A sessions, to the point of resembling the dynamics of the “TA” group meetings.

OF: However, we knew that the chances of people watching the “TA” documentary were really not that big, despite the packed theaters and the success of the festival. So we did a do-it-yourself guerilla marketing campaign to spread the message of the project.[7] We created a small arsenal of promotional assets like the song “El Corrido del Ciudadano” [8], which subverts the “narcocorrido” genre with lyrics taken from the film dialogues and interviews, to be played on the radio or on a rental car with a loudspeaker that rode around the city or outside of the cinema. We also sent out press releases, held interviews with different media outlets, and spent hours on the street handing out postcards as a way to jumpstart conversations with people about the issues related with violence that were affecting their cities. In a way, we were replicating the 12-step program sessions, but right there on the street. We were promoting a film screening, but below the surface we were having conversations as part of a broader art project addressing an issue that was starting to become out of control all over Mexico.

IB: What does “Tijuaneados” mean?

OF: The word “tijuaneado” is very common in relationship to the sale of used cars. In Tijuana, there’s a huge market for used cars that come from the US, and when people try to sell these vehicles they tell you “this car is not tijuaneado,” meaning it hasn’t been used in Tijuana—because once you drive the car in Tijuana most likely it will get damaged and will soon become ugly, dirty, and will lose value. But at some point, you might also hear the same word used in other contexts for things that are also affected or deteriorated. So, we appropriated the term for the “TA” 12-step program. A word that originally referred to cars was appropriated to talk about us––the people from Tijuana––and how the city affects us as human beings and vice versa.

IB: Something else that came up in the documentary is that people felt extreme fear and believed that if nothing was happening to them directly then nothing was really happening. It is a very common reaction in a society living with fear. During the dictatorship in Latin America, people would withdraw into their private lives or “self-censor”; some would leave the country and go into exile, others would become activists. Of course, there are many positions in between these two. But it was interesting to hear in the documentary that the people going to “TA” were there to change their attitude and the city.

JLF: The attitude of the people who attended the “TA” sessions in the face of violence in Tijuana was what motivated us, in part, to make the documentary. What we did was echo the conversations beyond the four walls of the space where they met, in the context of a city where fear and evasion prevailed. On the other hand, there was documented migration of hundreds of affluent families who moved to San Diego, California, leaving behind closed businesses and abandoned houses. But there were also citizens’ demonstrations against violence and activists, many of whom were directly affected by the turmoil, organizing search parties for the disappeared. During this period, we explored what drives us to take action against a situation of ungovernability and suffering, and the role pain and empathy play in motivating a person to seek an internal change. We did this through two projects: Participación and Tijuaneados Anónimos.

IB: What is Participación about and how does it relate (or not) to Tijuaneados Anónimos?

OF: In July of 2008, we were finishing details for the opening of the Tijuaneados Anónimos space in downtown Tijuana and we received an invitation to take part in Proyecto Cívico: Diálogos e Interrogantes [9], organized by Bill Kelley Jr. Our project was titled Participación, which revolved around one question: “How can we construct civic participation to confront the problem of violence?” The goal was to explore the role of citizenry in creating a public policy against violence in Tijuana. Participación began as a series of conversations between two local journalists, writer Daniel Salinas, photojournalist Omar Martínez, and members of our collective (then named Bulbo). Throughout the process, we kept a record of the discussions and shared relevant images and video clips on a Tumblr site.[10] By September of 2008, the city had gone through the worst period of violent homicides at the time, causing widespread indignation. Deeply shaken by the situation, the conversations turned towards issues that weren’t originally in our minds, like the effects of anger, pain, suffering, and having been the victim of violence to foster civic participation.

The final result of Participación was a video we made in collaboration with both journalists and a panel open to the public, which was held at the Centro Cultural Tijuana. The development of the project occurred in parallel with Tijuaneados Anónimos, and at some point, the conversations were in sync with what was being expressed at the “TA” meetings. The experience of doing Participación informed the story of our feature-length documentary about Tijuaneados Anónimos and helped to articulate the cinematic discourse. Also, the two journalists and activists involved in Participación were also film characters in the documentary. Looking back, Participación and Tijuaneados Anónimos were our responses to what we went through between 2005 and 2010. Our efforts to make sense of the violence and the deterioration of our city and our country. A way of taking action and working towards internal change. All this had a profound effect in our artistic practice.

IB: The way you work as a collective is unusual. As you say in your statement, you are “a hybrid between an art collective, media production company and distributor of cultural goods.” How do you navigate the space between activism, art, audiovisual creation, and also community engagement? Your project La Piñata Colaborativa, for instance, is about living with the Purepecha families in Rosarito, Baja California.

OF: The city of Rosarito, Baja California, has a community of about 250 Purepecha families, most of whom migrated from their ancestral homeland on the island of Janitzio, located in the State of Michoacan. Most of these families make piñatas for a living and work for one single distributor who then exports their work to the U.S. Over the years, they have developed a high level of craftsmanship which is quite remarkable because they learned the trade after resettling in their new environment. La Piñata Colaborativa [11] started in 2015 as a collaboration between Dignicraft and four families of Purepecha master artisans to design and create a series of piñatas as tools to talk about their identities as indigenous peoples and their history as a migrant community. We then made a documentary about the experience, started showing it together with the new series of piñatas, and whenever possible arranged for a few of the artisans to give talks or piñata making workshops. The following year, the project evolved into a series of conversations and collaborations between these master artisan families and cultural agents based in Los Angeles to explore issues related to fair trade, an alternative market for the commercial distribution of piñatas, and the community organizing made by other migrant indigenous peoples in Southern California, to name a few. La Piñata Colaborativa continues to evolve in unexpected ways, in part thanks to the respect and friendship that we have developed over the years with the master artisan families. The way we navigate the space between activism, art, community engagement, and audiovisual production is by focusing on the excitement of doing something together along with people you deeply respect. If there’s a point in the whole process where it feels like the project has taken on a life of its own and things start coming together by themselves, beyond the individual efforts of each collaborator, it means we are on the right track.

IB: With such a special way of working collaboratively, do you feel like you are part of the art world? How involved are you with other artists and collectives in Mexico? Are there other people in the art world with whom you feel connected or can collaborate?

JLF: Due to the nature of our work, we are constantly collaborating with people who are linked to the art world, whether academics, artists, or groups. But the core of our work occurs in the place where we are carrying out a project, and oftentimes the people we collaborate with are involved in a series of actions that might not be relevant to the art world; they are simply doing things. For example, in 2018 we held the Transcommunal Cornfield (Milpa Transcomunal) [14] in Basalto, a space for the exchange of knowledge and culture that we opened in the community of Santa Catarina Ayotzingo, State of Mexico. The purpose of this collaboration was to exchange knowledge about traditional sowing methods and to appreciate all of the work involved in this ancient practice. Vidal Campos, a Purepecha farmer, was our guest resident, and he brought purple corn seeds from his hometown in Michoacan to trade with local farmers Emiliano Leal and Juan Peña. We prepared about 2,000 square meters of land for them to sow and exchange know-how while we documented the process. Over the following months, we continued working the cornfield together with the locals. But the process of connecting with the farmers, preparing the land, and sowing the field felt far away from what we might consider to be within the realm of the art world. This is a common feeling in our practice. However, we understand this particular collaboration as an art project, and we might come across an opportunity to showcase it as part of an art exhibition. Also, half of our resources for Transcommunal Cornfield came from the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, a government fund for the arts in Mexico.

IB: Do you think your work is experienced differently in Mexico than it is abroad? I think one of the roles you take is the one of mediators. You spend a lot of time in a place working and researching, having conversations with certain groups, building relationships, and then you communicate something out of this process to different audiences, maybe broader audiences. What gets produced from those relationships fascinates me. While I was reviewing all of your different projects, the word “empathy” kept coming back to me. I haven’t been to Tijuana or most of Mexico, but I felt you were able to transmit this sense of empathy that I think is very important. What obstacles do you encounter with this type of methodology?

JLF: I would say that rather than encountering obstacles we encounter challenges. Oftentimes, we embark on projects that seem impossible to achieve because they depend on things beyond our control. So, we just focus on creating circumstances and building relationships, in hope that the outcome can take the shape of an artistic experience or a cultural product. I think of it as if preparing a dish using only the available ingredients, but always trying to do something good and nourishing. Empathy is one of those ingredients. It’s important to create a space of mutual respect with your collaborators. Then there’s always the need for resources to get things moving. In our case, we save money from commissioned film jobs, apply for a grant, or find ways of making a project self-sufficient. Another element is collaboration, which has been our core medium of communication between different people that we connect with, because we really believe that working together is a viable way to communicate with another person. If we work together, some of the differences start collapsing. Actions connect us on a deeper level and create a unique space for exchange. Being exposed to life in a border region also plays an important role because we get used to switching perspectives by going back and forth between Los Angeles and Tijuana. The border really forces you to switch perspectives all the time. And being involved in documentary filmmaking pushes us to confront different life perspectives or realities, so that’s another key component for us. By switching perspectives, we can bridge ideas between people.

OF: I would just add that we use the word “projects” when speaking of our undertakings, but I think they aren’t really projects in the sense of doing a job, shelving it, and moving onto the next one. Our art practice is our life, it’s what we do, and we do it whether we have a job or not. This gives our work a different level of commitment and responsibility. It changes the ball game, drastically.

IB: Like other socially engaged artworks, Dignicraft’s projects seem to be structured through processes of exchange and dialogue, unfolding over time. How do you maintain the relationships and infrastructures that you develop for each project?

JL: Each project generates a small network of relationships. This network is enriched whenever we begin a new project. Some of these relationships demand time and energy, while others are nourished by friendship or common interests. What we do is like having a map of this network based on our previous collaborations, and each time we are about to start a project we look for different ways to make connections and reincorporate those relationships in this new chapter of our practice. The relationships with collaborators transform along with life and can be constantly reactivated if both parties are willing to continue to work together, as if you were going through an endless journey.

OM: Our documentary films tend to be results of these processes of reconnecting with people who are part of an organically built network. So, a project does not end because human relationships do not end. And we need to assume responsibility for the connections that we jumpstart with our collaborators. The joy has been to see how life seems to connect us with others, continually leading us from one project to another and so on. It’s been that way since we started working together 20 years ago under the name “Bulbo” and “Galatea audio/visual” and it continues today with Dignicraft. So we’re hoping we can ride this wave as far as we can, as far as life will let us.

Dignicraft is a hybrid between an art collective, media production company, and distributor of cultural goods, inspired by human dignity and justice, the artisanal process of creation, and the potential of collaboration to spark change. The essence of the collective’s art practice is to encourage encounters normally not seen between people of different backgrounds. The group accomplishes this by producing documentaries, distributing cultural goods such as films, or imparting a collaborative workshop as part of a contemporary art project. The most important outcome for Dignicraft is the quality of the relationships they establish and their consequences. Dignicraft has been active since 2013 mainly in Tijuana, Mexico, and also transnationally in California, USA. The group was born of the evolution of the collective work that was started in 2000 under the name Bulbo and Galatea audio/visual. Currently, Dignicraft includes Paola Rodríguez, José Luis Figueroa, Omar Foglio, Blanca O. España †, David Figueroa, and Araceli Blancarte.

Ionit Behar is an art historian, curator and writer. She is a Ph.D. candidate in Art History at the University of Illinois at Chicago and her dissertation is titled Intimate Space and the Public Sphere: Margarita Paksa in Argentina’s Military Dictatorship. Her interests are focused on 20th century Latin American and North American art, art under censorship, socially engaged art practice, the history of exhibitions, and theories of space and place. She holds a Master’s degree in Art History, Theory and Criticism from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a Bachelor of Art Theory from Tel Aviv University, and a degree in Art Administration from the Bank Boston Foundation in Montevideo. She is the Director of Curatorial Affairs for Fieldwork Collaborative Projects NFP (FIELDWORK). She has served as the Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, as a Research Assistant for the exhibition “Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium” at the Art Institute of Chicago, and as a curatorial assistant at Gallery 400, UIC.

Notes

[1] Grant Kester, “Editorial: Spring 2015” in FIELD: A Journal of Socially Engaged Art Criticism) <https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/issue-1/kester>

[2] https://www.dignicraft.org/2002

[3] https://www.newsweek.com/worlds-new-culture-meccas-144621

[4] https://www.dignicraft.org/2008-a

[5] https://www.dignicraft.org/2008b

[6] https://www.filminlatino.mx/pelicula/tijuaneados-anonimos-una-lagrima-una-sonrisa

[7] https://youtu.be/RJYg7fJMDtg

[8] https://youtu.be/nlmrBetwfik

[9] http://proyectocivico.blogspot.com/

[10] https://participacion.tumblr.com/

[11] https://sites.saic.edu/talkingtoaction/artist/dignicraft/

[12] https://www.otis.edu/ben-maltz-gallery/talking-to-action-art-pedagogy-activism-americas

[13] https://sites.saic.edu/talkingtoaction/

[14] https://vimeo.com/348937228

Spanish Version

Fortaleciendo Encuentros: Dignicraft en Conversación con Ionit Behar

Traducción del inglés al español: Dignicraft, Ionit Behar and Cynthia Landa

Dignicraft es un híbrido entre un colectivo de arte, productora de medios y distribuidora de bienes culturales, inspirado en la dignidad y justicia humana, el proceso artesanal de la creación y el potencial de la colaboración para provocar cambio. La esencia de su práctica artística consiste en propiciar encuentros que normalmente no ocurren entre personas de distintos entornos. Esto se hace mediante la producción de documentales, la distribución de bienes culturales, como películas y artesanías con una gran historia detrás, o impartiendo talleres colaborativos como parte de un proyecto de arte contemporáneo. Lo más importante es la calidad de las relaciones que se establecen y sus consecuencias. Dignicraft ha estado activo desde 2013 principalmente en Tijuana, México, e internacionalmente, en California, USA. El grupo nació de la evolución del trabajo en colectivo iniciado en el año 2000, junto con otras personas, bajo el nombre de Bulbo y Galatea audio/visual. Actualmente, Dignicraft está integrado por Ana Paola Rodríguez, José Luis Figueroa, Omar Foglio, Blanca O. España †, David Figueroa y Araceli Blancarte.

Ionit Behar: A menudo sus proyectos comienzan con un lugar y un problema específico. Por ejemplo, unos de sus primeros proyectos, Tijuaneados Anónimos (2009), es un largometraje sobre Tijuana y un grupo de ciudadanos que participó en un workshop que ustedes diseñaron. El documental incluye los testimonios de los participantes del workshop, que comparten sus experiencias de la ola de violencia sin precedentes que estalló en Tijuana y en todo México en 2006. Me interesa la forma en que sus proyectos son locales pero también hablan de ideas más amplias y se hacen preguntas globales. Quizás lo que quiero decir es que su trabajo demanda sinceridad y, sobre todo, empatía. La idea de “empatía” en el arte socialmente comprometido ha devenido central en relación a su crítica, tanto de forma positiva como negativa. Grant Kester afirma que “es necesario comenzar de nuevo para comprender la naturaleza de lo político a través de un retorno práctico a las relaciones y a las preguntas más básicas; de uno mismo hacia el otro, de lo individual hacia lo colectivo, de autonomía y solidaridad, y de conflicto y consenso, a contracorriente del ahora dominante capitalismo neoliberal y en ausencia de teologías reafirmantes de movimientos revolucionarios del pasado.”[1] Es esto algo en lo que piensan cuando planean un proyecto o cuando se involucran en una situación nueva? Dirían que sus proyectos son tanto sobre la gente con la que se encuentran como sobre ustedes mismos?

José Luis Figueroa: Nuestro trabajo se desarrolla en la cotidianidad, a través de interacciones personales. Creemos que los problemas macro-estructurales se perciben en el día a día. Puede haber un acercamiento teórico al problema, pero al final de cuentas, se experimenta físicamente. La esencia de nuestra práctica artística o cultural es propiciar encuentros que normalmente no ocurrirían entre personas de diferentes entornos. Estos encuentros se logran a través de la colaboración, como un medio para crear un espacio común donde la comunicación, la comprensión, el intercambio y el aprendizaje puedan ser posibles. Intentamos crear encuentros entre individuos o grupos que puedan convertirse en redes de colaboración basadas en el reconocimiento del valor y respeto mutuo, ambos componentes clave de la empatía. Entonces, en lugar de buscar empatía, tratamos de evitar prejuicios, nos acercamos a personas, lugares o situaciones para aprender de ellas, poniendo atención durante todo el trayecto con el fin de ver si podemos ayudar en algo. La mejor manera de lograr esto es dejar que las acciones hablen por sí mismas. Hablar menos para hacer cosas juntos.

IB: Cómo es vivir y trabajar en Tijuana siendo un colectivo artístico? Gran parte de su trabajo es “site-specific”––basado en la investigación, el trabajo de campo, y las relaciones que han desarrollado en los sitios donde han tenido lugar sus proyectos. Me pregunto, cómo contribuyen sus experiencias en Tijuana a sus proyectos en diferentes lugares?

Omar Foglio: Actualmente estamos desarrollando un espacio para residencias e intercambio de saberes cuyo nombre es “Basalto”, está ubicado en las afueras de la Ciudad de México, en el poblado de Santa Catarina Ayotzingo, Estado de México. Al principio creíamos que el lugar tenía muy poco en común con nuestra ciudad de origen, Tijuana; sin embargo, a medida que pasamos mayor tiempo trabajando con los miembros de la comunidad, más nos damos cuenta de que el Valle de México tiene una dinámica muy parecida a la que existe entre Tijuana y el Sur de California, donde la vida cotidiana está determinada por la situación fronteriza. El Valle de México limita territorialmente con la Ciudad de México, esta división entre lo urbano y la periferia evidencia la desigualdad de oportunidades, representa para los residentes de 3 a 4 horas de desplazamiento del hogar a los sitios de trabajo y la sensación de habitar la inmensa periferia subordinada al centro político, económico y cultural del país. En ese sentido, nuestra experiencia de vivir en la frontera entre México y EEUU nos ha servido para entender y conectar con un lugar ubicado casi a dos mil millas de nuestra casa.

JLF: En nuestro caso, la vida en Tijuana ha sido binacional y bicultural. Esto nos ha obligado a cambiar constantemente nuestras perspectivas sobre sistemas de valor, formas de pensar e incluso ritmos de trabajo. Esta habilidad para transitar entre culturas ha sido como un entrenamiento que nos ha preparado para los proyectos que hemos hecho fuera de la ciudad; especialmente el trabajo colaborativo que hicimos con familias de la comunidad Purépecha de México y Estados Unidos.

OF: En perspectiva, nuestro trabajo se ha transformado en respuesta a lo que ha ocurrido en la ciudad. Cuando empezamos Bulbo [2], en los inicios del año 2000, como un programa de televisión, sabíamos que no éramos representados por los medios masivos. La mayoría del contenido que recibíamos provenía de EEUU o de la Ciudad de México, así, no había lugar para ver a nuestra ciudad, a nosotros mismos, nuestra generación y la gente que nos rodeaba. Hay que considerar que esto fue mucho antes de que las redes sociales se convirtieran en lo que son ahora, por eso, era todavía más difícil crear contenido distinto e intervenir en los medios tradicionales. Al principio, los temas que abordamos eran acerca de nuestra vida cotidiana y sobre personas que realizaban proyectos artísticos, musicales, creativos o independientes. En ese tiempo, todo esto coincidía con lo que veíamos en la ciudad, estaban ocurriendo muchas cosas, fue una época muy emocionante.[3] Sin embargo, por 2006 y especialmente en 2008 la situación en Tijuana empezó a cambiar, la violencia relacionada con el crimen organizado comenzó a salirse de control; hubo muchos secuestros y todo iba en decadencia. Se sintió como si la ciudad hubiera entrado en un periodo de depresión y no consideramos correcto seguir celebrando y pretendiendo que no estaba sucediendo nada. Entonces supimos que teníamos que hacer algo, con nuestros propios medios, para combatir la situación, a partir de ahí empezamos a trabajar en los proyectos: Participación [4] y Tijuaneados Anónimos.[5]

IB: Algunos aspectos de su trabajo me recuerdan al arte de los años sesenta y setenta en Argentina, durante la dictadura. Me refiero más específicamente al Arte de los Medios de Comunicación de Masas, que fue un grupo artístico experimental formado por Eduardo Costa, Roberto Jacoby, y Raúl Escari en 1966. Este grupo usaba medios de comunicación masiva como formato artístico para cuestionar problemas relativos a la verdad y al poder de los medios en la sociedad. Otro ejemplo importante es Tucumán Arde. Tucumán, una provincia del noroeste de Argentina, fue extremadamente afectada por la dictadura; el pueblo fue llevado a la pobreza y a la hambruna debido al cierre de varias granjas e ingenios azucareros. Artistas de Rosario y de Buenos Aires formaron un movimiento de contrainformación, interviniendo los medios de comunicación masiva y revelando así las mentiras del régimen militar acerca de la situación en Tucumán. Los artistas buscaban mostrar la verdad. Creo que su documental, Tijuaneados Anónimos, en parte tiene que ver con revelar la verdad. Podrían contarme un poco sobre cómo surgió este proyecto? El componente principal es el documental, pero hay otros elementos que también conforman Tijuaneados Anónimos, ¿no? Cuéntenme sobre esos elementos también, por favor.

JLF: La ciudad cambió. Empezamos a ver muchas situaciones violentas, encontrábamos cadáveres colgando de puentes y otras cosas terribles que estaban impactando la vida de todos. No solo era eso, debido a su ubicación geográfica, Tijuana tiene un enorme flujo de personas, bienes y cultura que van y vienen a través de la frontera, pero igual sucede con drogas, armas, dinero, entre otros. Nos parecía que la ciudad era un lugar caótico y pensamos que sería bueno tener un programa de autoayuda donde las personas pudieran lidiar con lo que estaba sucediendo en la ciudad en ese momento. Posteriormente, con base en la estética del logotipo de Alcohólicos Anónimos “AA”, creamos una identidad gráfica para una comunidad imaginaria llamada “Tijuaneados Anónimos”. El plan era hacer calcomanías, posters, pins y distribuirlos en la ciudad como un gesto irónico parte de un proyecto artístico. La idea original evolucionó a tener un lugar físico abierto al público donde un grupo de personas hacía reuniones de apoyo psicológico bajo el nombre “Tijuaneados Anónimos”.

OF: Fue muy difícil para nosotros enfrentarnos a la situación que se vivía en la ciudad y buscar la manera de hablar de ello. El espacio físico de Tijuaneados Anónimos estaba ubicado en el centro de Tijuana y estaba abierto a cualquier persona que pasara por ahí y quisiera formar parte de las conversaciones. Esa dinámica duró alrededor de un año. Al mismo tiempo, participamos con la recreación del espacio de “TA” en una exhibición artística del San Diego Museum of Art llamada “Inside the Wave: Six San Diego / Tijuana Artists Construct Social Art” , además, creamos una instalación, presentando videoclips de las sesiones del grupo y el logo de “TA”, en el 18th Street Arts Center in Santa Monica para la exhibición: “The Future of Nations – Part III: Citizen Artists Making Emphatic Arguments”. Después de unos meses, el grupo tomó vida propia, escuchamos las historias que contaba la gente que asistía y sentimos la necesidad de llevar esa conversación más lejos. A partir de ahí empezamos a trabajar en el documental [6] para contar las historias de las personas que eran parte del programa de los “12 pasos”.

JLF: El documental nos dio la oportunidad de viajar por las ciudades más importantes de México como parte del Festival de Documentales Ambulante. La película propició que las personas reflexionaran sobre problemas similares que enfrentaban en sus propias ciudades. A razón de esto nos dimos cuenta de que la situación que atravesaba Tijuana, en términos de violencia, estaba solo unos pasos adelante respecto a lo que estaba empezando a ocurrir en todo México. Una clara muestra de esto fue la necesidad de los espectadores de hablar durante las sesiones de preguntas y respuestas al terminar la presentación del documental, a tal grado que se asemejaba a las dinámicas que sucedían en las reuniones de “TA”.

OF: Sin embargo, sabíamos que la probabilidad de que la gente viera el documental “TA” no era muy alta, a pesar del éxito en taquilla del festival. Así que preparamos una campaña de marketing de guerrilla, al estilo “hazlo tú mismo”, para difundir el mensaje del proyecto.[7] Creamos un pequeño arsenal de materiales promocionales, como la canción “El Corrido del Ciudadano” [8], que subvierte el género del “narcocorrido” utilizando letras basadas en los diálogos y entrevistas del documental, para reproducirse en la radio o en un auto rentado con unas bocinas potentes que recorriera la ciudad o se estacionara afuera del cine. También enviamos boletines de prensa, dimos entrevistas a diferentes medios de comunicación y pasamos horas en la calle repartiendo volantes como un medio para iniciar conversaciones sobre los problemas relacionados con la violencia que estaban afectando a sus ciudades. De alguna manera, estuvimos replicando las sesiones del programa de los 12 pasos, pero en la calle. Estábamos promocionando la presentación de una película, pero de manera subyacente estábamos provocando conversaciones como parte de un proyecto más amplio que abordaba un problema que se estaba saliendo de control en todo México.

IB: ¿Que quiere decir “Tijuaneados”?

OF: La palabra “tijuaneado” se relaciona comúnmente con la venta de un automóvil. En Tijuana, existe un amplio mercado para la venta de autos usados que vienen de los Estados Unidos, cuando las personas intentan vender un vehículo dicen “este carro no está tijuaneado”, esto significa que no ha sido utilizado en Tijuana (porque al conducir un auto en Tijuana es muy probable que se dañe, se vea feo, sucio y que pronto pierda su valor). En cierto punto, esa palabra también se usaría en contextos relacionados con el deterioro o maltrato. En ese sentido, nos apropiamos del término “TA” para designar un programa de “12 pasos”. Una palabra que originalmente hacía referencia a vehículos se tomó como propia para designarnos, para hablar sobre nosotros (los habitantes de Tijuana) y de qué manera la ciudad nos impacta como seres humanos y viceversa.

IB: Algo más que surgió en el documental es que la gente sentía un miedo extremo y creía que si no les pasaba nada directamente a ellos, en realidad no estaba pasando nada. Ésta es una reacción muy común en una sociedad que vive con miedo. Durante las dictaduras en Latinoamérica, la gente se replegó hacia sus vidas privadas, o se auto-censuró; algunos dejaron sus países y se exiliaron, otros se convirtieron en activistas. Por supuesto que hay muchas posiciones intermedias. Pero es muy interesante escuchar en el documental que la gente que iba a “TA” estaba allí para cambiar su actitud y para cambiar la ciudad.

JLF: La actitud, frente a la violencia en Tijuana, de las personas que asistían a las sesiones de “TA” fue, en parte, lo que nos motivó a realizar el documental. Lo que hicimos fue resonar en el exterior las conversaciones que se llevaban a cabo dentro del espacio donde se reunían, en el contexto de una ciudad donde prevalecen el miedo y la evasión. Por otro lado, había registros de la migración de cientos de familias pertenecientes a la clase alta que se mudaron a San Diego, California, y dejaron a su paso negocios cerrados y casas abandonadas. También hubo protestas ciudadanas y participación de activistas en contra de la violencia, muchos de los cuales habían sido directamente afectados por los disturbios, quienes organizaron grupos de búsqueda de los desaparecidos. Durante este periodo, exploramos qué es lo que nos motiva a actuar en contra de una situación de ingobernabilidad y sufrimiento, así como, el rol que juegan el dolor y la empatía en la motivación de una persona para buscar un cambio interno. Hicimos esto a través de dos proyectos: “Participación” y “Tijuaneados Anónimos”.

IB: ¿Sobre qué es Participación y cómo se relaciona (o no) a Tijuaneados Anónimos?

OF: En julio de 2008, mientras estábamos terminando de afinar los detalles para la apertura del espacio de Tijuaneados Anónimos en el centro de Tijuana, recibimos una invitación a participar en “Proyecto Cívico: Diálogos e Interrogantes” [9], organizado por Bill Kelley Jr. Nuestro proyecto se titulaba “Participación” y se desarrollaba alrededor de la siguiente pregunta: “¿cómo podemos enfrentar el problema de la violencia a través de la participación cívica? El objetivo era explorar el papel que juega el civismo en la creación de una política pública en contra de la violencia en Tijuana. “Participación” empezó como una serie de conversaciones entre dos periodistas locales, el escritor Daniel Salinas y el fotoperiodista Omar Martínez, y miembros de nuestro colectivo (antes llamado Bulbo). Durante el proceso llevamos el registro de las discusiones y compartimos imágenes y clips de video relevantes en un blog de Tumblr.[10] En septiembre de 2008, la ciudad vivió el peor periodo de homicidios violentos del año, eso provocó indignación generalizada entre la población. Conmovidos profundamente por la situación, dirigimos las conversaciones hacia problemas que no estaban originalmente en nuestra mente, como, los impactos del enojo, dolor, sufrimiento, haber sido víctima de la violencia, para promover la participación cívica.

El resultado final de “Participación” fue un video que hicimos en colaboración con los dos periodistas y un panel de discusión abierto al público que se llevó a acabo en el Centro Cultural Tijuana. El proyecto se desarrolló al mismo tiempo que “Tijuaneados Anónimos”, y en un punto, las conversaciones se sincronizaron con lo que se manifestaba en las sesiones de “TA”. La experiencia de hacer “Participación” nutrió la historia de nuestra película documental acerca de “Tijuaneados Anónimos” y contribuyó a la articulación del discurso cinematográfico. Además, los periodistas y activistas involucrados en “Participación” fueron personajes en el documental. En perspectiva, “Participación” y “Tijuaneados Anónimos” fueron nuestra respuesta a lo que enfrentamos entre el año 2005 y 2010. Nuestros esfuerzos para entender la violencia y deterioro de nuestra ciudad y de nuestro país. Una forma de tomar conciencia y trabajar para lograr un cambio interno. Todo esto tuvo un profundo impacto en nuestra práctica artística.

IB: Como colectivo trabajan de una forma poco común. Como dicen en su statement, son “un híbrido entre colectivo artístico, empresa productora de medios, y distribuidor de bienes culturales.” ¿Cómo navegan el espacio entre activismo, arte, creación audiovisual, y también compromiso comunitario? Su proyecto La Piñata Colaborativa, por ejemplo, se trata de la experiencia de vivir con las familias Purepecha en Rosarito, Baja California.

OF: En la ciudad de Rosarito, Baja California, habita una comunidad de aproximadamente 250 familias purépechas, la mayoría de estas proviene de la ancestral isla de Janitzio, ubicada en el estado de Michoacán. Muchas de estas familias hacen piñatas para sobrevivir y trabajan para un solo distribuidor que exporta las piezas a los Estados Unidos. Con el paso de los años, han desarrollado un alto nivel de destreza manual que es digno de tener en cuenta porque aprendieron el oficio después de asentarse en su nuevo entorno. “La Piñata Colaborativa” [11] empezó en 2015 como un proyecto de colaboración entre Dignicraft y cuatro familias de maestros artesanos purépechas con el objetivo de diseñar y crear una serie de piñatas que funcionaran como herramientas para hablar sobre su identidad como indígenas y de su historia como una comunidad migrante. Después hicimos un documental acerca de la experiencia, lo presentamos junto con la serie de piñatas que se crearon y, cuando fue posible, preparamos las condiciones para que algunos artesanos dieran pláticas y talleres sobre cómo hacer piñatas. Al año siguiente, el proyecto se transformó en una serie de conversaciones y colaboraciones, entre dichas familias de maestros artesanos y agentes culturales de la ciudad de Los Ángeles, sobre los problemas relacionados con el comercio justo, medios alternativos para la distribución comercial de las piñatas y la organización comunitaria liderada por otros grupos indígenas migrantes del Sur de California, por mencionar algunos. “La Piñata Colaborativa” continúa evolucionando en formas inesperadas, en parte gracias al respeto y amistad que hemos desarrollado en el transcurso de los años con las familias de los maestros artesanos. La manera en que navegamos el espacio entre activismo, arte, integración comunitaria y producción audiovisual es concentrando las energías en la emoción de hacer algo juntos, en colaboración con gente que respetamos profundamente. Si en algún momento del proceso sentimos que el proyecto ha tomado vida propia y las cosas suceden sin necesidad de nuestra intervención, entonces, significa que vamos por buen camino.

IB: Con un modo tan especial de trabajar colaborativamente, sienten que son parte del mundo del arte? ¿Cuán involucrados están con otros artistas y colectivos en México? ¿Hay otra gente en el mundo del arte con la que se sientan conectados, o con la que puedan colaborar?

JLF: Debido a la naturaleza de nuestro trabajo, constantemente estamos colaborando con personas conectadas con el mundo del arte, ya sean académicos, artistas o grupos. Sin embargo, el corazón de nuestra práctica está en el lugar donde desarrollamos un proyecto, frecuentemente las personas con las que colaboramos realizan acciones que pudieran no ser relevantes en el mundo del arte; simplemente están haciendo “cosas”. Por ejemplo, en 2018 llevamos a cabo “Milpa Transcomunal” [14] en Basalto, un espacio para el intercambio cultural y de saberes que abrimos en la comunidad de Santa Catarina Ayotzingo, Estado de México. El propósito de esta colaboración era intercambiar conocimiento sobre el método de siembra tradicional y reconocer todo el trabajo que representa esta práctica ancestral. Vidal Campos, un campesino purépecha, fue nuestro invitado en la residencia, él proveyó semillas de maíz morado originarias de su pueblo natal en Michoacán para hacer un intercambio con Emiliano Leal y Juan Peña, campesinos locales. Preparamos cerca de 2,000 metros cuadrados de tierra para que sembraran e intercambiaran sus métodos de siembra, mientras nosotros registrábamos el proceso. Durante los meses siguientes, seguimos trabajando en el campo de maíz junto con los locales. El proceso de conectar con los campesinos, preparar la tierra y sembrar el campo parece estar muy lejos de lo que puede considerarse como parte del medio artístico, este es un sentimiento frecuente en nuestra práctica. No obstante, consideramos esta colaboración en particular como un proyecto de arte, y probablemente tengamos la oportunidad de presentarlo en una exhibición artística. Además, la mitad de los recursos para la Milpa Transcomunal llegaron a través del apoyo del Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, un fondo gubernamental para el desarrollo de las artes en México.

IB: Piensan que su trabajo se vive de forma distinta en México que en el exterior? Creo que uno de los roles que ustedes toman es el de mediadores. Pasan un largo tiempo en un lugar trabajando e investigando, teniendo conversaciones con ciertos grupos, cultivando relaciones, y luego comunican algo acerca de este proceso a diferentes audiencias, quizás a audiencias más amplias. Lo que se produce en esas relaciones me fascina. Mientras estaba repasando todos sus diferentes proyectos, no podía dejar de pensar en la palabra “empatía”. Nunca he ido a Tijuana ni a la mayor parte de México, pero siento que fueron capaces de transmitir esta sensación de empatía que creo que es muy importante. ¿Qué obstáculos encuentran con este tipo de metodología?

JLF: Diría que más que encontrar obstáculos, hemos enfrentado retos. Frecuentemente emprendemos proyectos que parecen imposibles de realizarse porque dependen de factores fuera de nuestro control. Entonces, solo nos concentramos en crear las condiciones para construir relaciones, esperando que el resultado tenga la forma de una experiencia artística o de un producto cultural. Esto lo comparo con preparar un platillo con los ingredientes que se tienen a la mano, pero siempre con la intención de que resulte algo bueno y nutritivo. La empatía es uno de esos ingredientes. Es importante crear un entorno de respeto mutuo entre los colaboradores. Siempre existe la necesidad de buscar recursos para echar a andar las cosas. En nuestro caso, buscamos la manera de ahorrar parte del dinero que ganamos mediante trabajos de cine comisionados, solicitando alguna beca o encontramos formas de hacer que un proyecto sea autosuficiente. Otro elemento a considerar es la colaboración, que ha sido nuestro medio de comunicación más importante con las diferentes personas con quienes hemos conectado, pues creemos, sinceramente, que el trabajar juntos es una forma viable de comunicarse con los demás. Si trabajamos juntos, las diferencias entre nosotros empiezan a disolverse. Las acciones nos conectan en un nivel más profundo y se desarrolla un entorno único para el intercambio. El estar expuestos a la vida de la frontera también juega un rol importante porque gracias a esto estamos acostumbrados a cambiar perspectivas debido al ir y venir entre Los Ángeles y Tijuana. Vivir en la frontera te obliga a alternar perspectivas constantemente y estar relacionado con la producción documental te empuja a confrontar diferentes formas de vida o realidades, ese es otro componente clave en nuestra práctica. Al alternar perspectivas, intentamos que las ideas sean puentes que conecten a las personas.

OF: Solo me gustaría agregar que usamos la palabra “proyectos” para referirnos a nuestras actividades, pero no los consideramos realmente como ‘proyectos’, en el sentido de realizar un trabajo, archivarlo y seguir adelante con el próximo. Nuestra práctica es nuestra vida, es lo que hacemos, y lo hacemos así tengamos un proyecto o no. Esto le otorga a nuestro trabajo un sentido de compromiso y responsabilidad; con esto las reglas del juego cambian drásticamente.

IB: Tal como otras obras comprometidas socialmente (“socially engaged art”), sus proyectos parecen estar estructurados a través de procesos de intercambio y de diálogo, que se desarrollan a lo largo del tiempo. ¿Cómo mantienen las relaciones e infraestructuras que desarrollan para cada proyecto?

JL: Cada proyecto que hacemos genera un conjunto de relaciones interpersonales. Esta red se enriquece cada vez que iniciamos un nuevo proyecto. Algunas de esas relaciones requieren tiempo y energía, mientras que otras se nutren por la amistad e intereses mutuos. Cada vez que iniciamos un proyecto nuevo buscamos la manera de incorporar las conexiones que hicimos en trabajos anteriores, hacemos como si tuviéramos una especie de mapa de las colaboraciones anteriores y con base en esto creamos nuevas relaciones y recuperamos las previas. Las relaciones que establecemos con los colaboradores se transforman durante el transcurso de la vida, se pueden reactivar constantemente si ambas partes están dispuestas a seguir trabajando juntos, como si se tratara de un trayecto sin fin.

OM: Nuestras películas documentales suelen ser resultado de esos procesos de reconexión con personas que forman parte de una red orgánica de colaboración. Así, el proyecto no termina porque las relaciones interpersonales no lo hacen, de este modo, asumimos la responsabilidad de las relaciones que provocamos con nuestros colaboradores. La satisfacción ha sido ver cómo la vida parece conectarnos con los demás y cómo continuamente nos lleva de un proyecto a otro. Así ha sido desde que empezamos a trabajar juntos hace 20 años bajo el nombre “Bulbo” y “Galatea audio/visual” y sigue siendo de esta forma hasta la fecha en Dignicraft. Esperamos que tengamos la fortuna de navegar esta ola lo más lejos posible, lo más lejos que la vida nos permita.

Dignicraft es un híbrido entre un colectivo de arte, productora de medios y distribuidora de bienes culturales, inspirado en la dignidad y justicia humana, el proceso artesanal de la creación y el potencial de la colaboración para provocar cambio. La esencia de su práctica artística consiste en propiciar encuentros que normalmente no ocurren entre personas de distintos entornos. Esto se hace mediante la producción de documentales, la distribución de bienes culturales, como películas y artesanías con una gran historia detrás, o impartiendo talleres colaborativos como parte de un proyecto de arte contemporáneo. Lo más importante es la calidad de las relaciones que se establecen y sus consecuencias. Dignicraft ha estado activo desde 2013 principalmente en Tijuana, México, e internacionalmente, en California, USA. El grupo nació de la evolución del trabajo en colectivo iniciado en el año 2000, junto con otras personas, bajo el nombre de Bulbo y Galatea audio/visual. Actualmente, Dignicraft está integrado por Ana Paola Rodríguez, José Luis Figueroa, Omar Foglio, Blanca O. España †, David Figueroa y Araceli Blancarte.

Ionit Behar es una historiadora de arte, curadora y crítica de arte. Es candidata a doctorado de Historia de Arte en la Universidad de Illinois en Chicago (University of Illinois at Chicago) y su tesis es titulada Espacios Íntimos y Públicos: Margarita Paksa durante la Dictadura Militar Argentina. Sus intereses están enfocados en el arte del siglo XX en Latino América y Estados Unidos, arte conceptual, arte político, arte bajo censura, historia de exposiciones, y teorías del espacio. Recibió un Master en Historia del Arte de la Escuela de Artes de Chicago (School of the Art Institute of Chicago), se licenció Magna Cum Laude en Teoría del Arte en el Programa Multidisciplinario de las artes de la Universidad de Tel Aviv y realizó estudios en Gestión Cultural en la Fundación Bank of Boston en Montevideo. Actualmente es la Curadora de el colectivo Fieldwork Collaborative Projects (FIELDWOR). Fue curadora en el Instituto Spertus, Investigadora para la exposición “Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium” en el Instituto de Arte de Chicago (Art Institute of Chicago), y Asistente de Curador en Gallery 400.

Notas

[1] Grant Kester, “Editorial: Spring 2015” in FIELD: A Journal of Socially Engaged Art Criticism) <https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/issue-1/kester>

[2] https://www.dignicraft.org/2002

[3] https://www.newsweek.com/worlds-new-culture-meccas-144621

[4] https://www.dignicraft.org/2008-a

[5] https://www.dignicraft.org/2008b

[6] https://www.filminlatino.mx/pelicula/tijuaneados-anonimos-una-lagrima-una-sonrisa

[7] https://youtu.be/RJYg7fJMDtg

[8] https://youtu.be/nlmrBetwfik

[9] http://proyectocivico.blogspot.com/

[10] https://participacion.tumblr.com/

[11] https://sites.saic.edu/talkingtoaction/artist/dignicraft/

[12] https://www.otis.edu/ben-maltz-gallery/talking-to-action-art-pedagogy-activism-americas

[13] https://sites.saic.edu/talkingtoaction/

[14] https://vimeo.com/348937228