Curatorial Activism in Iran

Elham Puriya Mehr

Introduction

Within the last decades, contemporary art as a “field” of action has become significantly socialized , finding its way into public space, often to merge or overlap with that of political activism. Consequently, the number of curators worldwide utilizing their newfound “power” for changing societal structures has increased. Understanding curation as an actual event itself [1], a form of critical thought and action that aims to question and change the status quo and has a mutual relationship with society. In countries like Iran, due to the restrictions on the use of public spaces, this practice is contextually interwoven with activism from the very first moment. So, is there a sensitivity to how the context controls curatorial activism? And how does this kind of action separate itself from existing norms, and allow continuation of this action? This article seeks to open the discourse of shifting the “public space” to the “public sphere,” which functions as a conceptual foundation for deliberation, in order to arrive at a consensus for the common good. As activism, and to elaborate, it examines a curatorial project Club 29 that employed storytelling as a strategy for constructing a “public sphere” and deconstructing the normalization of power. This performance-based project was presented in a temporary “public space,” Ag Experiment in Tehran, 2018.

Curatorial, “Public Space,” and “Power”

The relationship between the representation of art and politics has been one of the major concerns of Iranian artists and curators in recent decades; many of them have not been able to display their work due to political control from the government. After the revolution of Iran in 1979, the art scene witnessed an obvious dichotomy emerge between governmental and non-governmental art. This division has had a great impact on the way art is represented/presented. Governmental art freely has access to all public spaces, while non-governmental art could only be exhibited in the closed and safe spaces of the galleries. So, curatorial strategies, rather than considering the presentation, have led more to the representation of artworks in white cubes. In the meantime, political themes of exhibitions/projects have tended to be seen as an alternative action for art activism. Yet, this situation has not survived in the face of the government’s enthusiasm for buying artworks as profitable capital in the last decade. This policy, which began during the administration of Alireza Sami Azar at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 1999 under the pretext of bringing art, people and government closer, has encouraged galleries to focus more on selling artworks to private and governmental collections. This has promoted the loss of existing potential in the galleries as the only accessible public spaces. Given these obstacles, art professionals struggle to perform activism in public spaces. How then can these efforts be accomplished? What if the context causes and leads them into a different result? What if those in power uses activist action to normalize the existing politics?

The term normalization connotes concepts such as standardization, conformity, and control. In Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975), normalization is explained as a way of exerting control within society, of applying the most powerful weapon, which he calls “disciplinary power,” without intervening with visible force or violence of any sort. This “disciplinary power” developed in different contexts (such as schools or factories), becomes a prevalent aspect of social structure in modern and contemporary societies. Therefore, ending activist action takes place through normalizing the existing politics. If so, curation paradoxically takes place in between two states of activism, and in being institutionalized, becomes a tool of developing what it opposes. One of the factors this situation is when the act of presentation gets detained in the aesthetics of activism instead of engaging in the activist action. Such a situation could be changed when the crucial factor of public participation enters the field. Accepting the fact that this factor could balance “power,” and play a fundamental role in the curatorial implementation, we return to the question of which “field” could be appropriate for this participation?

Public spaces can offer multiple places, depending on the society’s economy and culture. These temporary arenas, like an intersection, present the moment of the public encountering the unequal distribution of “power.” Simon Sheikh in “Public and Post Public” emphasizes that: “…we must understand public spaces not only in the public/private divide, but also in relations to spaces of production. That is, how public spaces emerge through production, as ideological constructions, and through economic development. However, today, we would not describe public spaces only in dialectics of class struggle, but rather as a multiplicity of struggles, among them struggles for recognition, partly in shape of access to the “public space”, as well as the struggle for the right to struggle itself, for dissent.” [1]

To operate curatorial activism in public spaces, one cannot ignore the fundamental differences of these spaces in various contexts that provide different potentials. Owing to this fact, understanding the structures and infrastructures of public spaces in Iran requires recognition of normative “rules” that are embedded in the definition of society and its relation to “power.” For Islamic philosophers such as Farabi and Suhrawardi, whose theories have been very influential in the ruling ideology, “power” is not an intervening force/network that exists in everything, but a vital factor that balances society qua. They liken the relationship between the public and the “public space” to the human body and its parts. And since they generally consider the city as a “public space,” they emphasize that this inseparable relationship flows through “power.” For instance, Farabi visualizes this belief as follows:

“Both the city and the household have an analogy with the body of the human being. The body is composed of different parts …, each doing a certain action, so that from all their actions they come together in mutual assistance to perfect the purpose of the human being’s body. In the same way, both the city and the household are composed of different parts of a definite number …, each performing on its own a certain action, so that from their actions they come together in mutual assistance to perfect the purpose of the city or the household.” [2]

According to this definition, the concept of “public space” is perceived as a communal social space, which is open and accessible to all people regardless of social identity, and what happens to each person affects society. This approach, without considering the political situation of contemporary Iran, can be both advantageous and problematic, because on one hand, it fosters a form of public relations that leads to social interaction. The result could be realized in small communities such as “squares”, “bazaars”, etc., which are the fields for social actions and public participations. On the other hand, this attitude hijacks the notion of individualized desire and eliminates any possibility of opposition and any activist action which can cure the society, since the slightest change against “power” means the destruction of the society.

What seems notable is that this regular and cohesive model still is repeating in the politics of the relationship between public spaces and the public interactions in nowadays present-day Iran. The difference is that the added modernist approaches have accelerated the subjugation of public spaces by “power.” For example, “squares” as public spaces in which people used to have social interactions now function as only underground spaces of passing through and have lost their social potentials. Due to the urban policies, public places, day by day, are being virtually out of public access, and publics are becoming more and more socially separated. This “symbolic order” is building “planned,” “controlled,” and “ordered” spaces, in the sense that it has an essential role in the development and continuation of its “power.”

Public Spheres, Storytelling, and Activism

Facing such a situation gives us the opportunity to think about curatorial strategies in response to the lack of public accessibility. My suggestion in this text is that planning strategies have the potential to change the purpose of spaces, which means, shifting the focus from recapturing public spaces into building temporary public spheres.

For example, In May 2018, I curated the Club 29 project in collaboration with Canadian and Iranian artists to turn a two-floor old space into a club for a while. This project, which took more than three years of research, resembled an art club in Iran in the 1960’s called Rasht 29 Club, founded and run by architect Kamran Diba, sculptor Parviz Tanavoli, and musician Roxana Saba from 1967 to 1970. This club, which took its name from its address on Rasht Street in Tehran, had not been established to generate income and was thus considered to be the first private and non-profit art space in Iran. The programs and events taking place at Rasht 29 had turned it into one of the most unique of its time: a permanent exhibition space and dining hall where artists, poets, writers, architects, filmmakers and other intellectuals of the time could gather, dine, socialize and engage in dialogue and discourse with other people who would frequent the club. Many trends and developments began at Rasht 29. Tanavoli and Diba permitted the use of some parts of the premise as an artist studio and theater rehearsal room. Inspired by a convent that he had visited in Italy, Tanavoli decided to issue memberships to artists in exchange for their artworks. Diba drafted the initial plans for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art under the influence of the events and programs of the club. And, the first Iranian fashion label was founded by Keyvan Khosravani in the garage of the club building. Rasht 29 differed from the other art spaces in that it invited viewers to join and become a part of the exhibitions/projects by meeting the artists and dining with them within that space. Another result of this space was the dialogue it created between artists and visitors. [3]

The Club 29 project restaged a creative group structure, which unified exhibition spaces with the production of art. Instead of becoming involved in the usual issues of “power,” hegemony, hierarchy, control, value and order of the exhibition space, it focused on the relationship between people and the many performance-based events. The most important achievement of the project was creating a social setting within which participants could play a part in creating art along with the artists and the curator. The initial idea was to build an open space like a café to engage people from different backgrounds. Since the building was new to the art scene, and therefore not known as being a public space, this was improbable, but there was the opportunity to involve many groups of people as performers and get them willing to participate. The whole project was considered as a fluent group storytelling event to create a temporary “public sphere.” In fact, the main goal was using storytelling to build a community with the help of the people. Assuming that public storytelling is a form of activism that gives voices to the people, Club 29 was concentrated on the “power” of individual stories as well as the Rasht 29 Club’s stories.

The philosopher Hannah Arendt believes that storytelling can be used to reopen the idea of “public space” and to facilitate dialogue/action amongst citizens aimed at attaining a more participative society. She regards storytelling as the only real political action, as it opens up the idea of “public space” where everybody is invited to take part in the discussion in which decisions upon the polis – the common realm – are taken together. [4] But how can this “common realm” stay away from the path of normalization? Usually, it is possible that curatorial practices symbolically lead the project to a platform for governmental control. Especially thematic projects that are framed on the one hand by a historicizing drive, and on the other hand, by the arbitrary nature of curatorial agency. As a cure, Club 29 refrained from any political slogans and practiced to keep the project away from politicization. The club was not a place for “catharsis,” where storytellers could unload a heavy burden from their shoulders, but it was a “public sphere” exchanging the stories. It is critical to be aware that sometimes not acting is a stronger gesture than acting, and that not being political may be political.

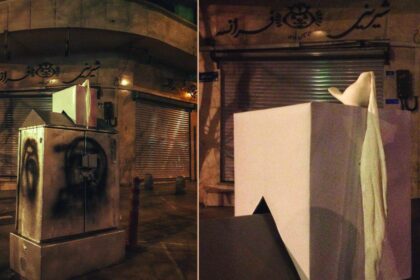

With all these attempts to keep public, common realms removed from the path of normalization, we can observe that normalization eventually enters our spaces through the back door. This is where being temporary comes to action. Temporality is a significant factor that has a very practical role in the implementation of these types of spaces. It plays a central role in the identity of all public spheres, as it takes form through rapidly changing urban, political and social situations. This flexibility in temporality helps the strategies activist actions to be sustained, that is, to avoid normalization. The Club 29 project evoked the mentality that the best way to struggle with this trap is try to build public spheres in very unexpected areas. Those that exist in people’s daily lives. From educational spaces to restaurants, cafes, and all the places where people are involved in society. This strategy of space appropriation allows curatorial activism to imperceptibly make fundamental positive changes for the publics. With this in mind, curatorial approaches, rather than creating a “power spectacle,” could work alongside activism.

For more information: www.club29.ca

Elham Puriya Mehr is an artist, curator, and lecturer based in Vancouver, BC. She received her BA and MA from the Tehran University of Art, and her Ph.D. in Art Research (Cultural Discourse of Curating in Contemporary Art of Iran) from Alzahra University in Tehran. Her researches focus on curatorial knowledge in social contexts, non-Western curatorial methodologies, and public engagement. She investigates innovative methods to involve publics in art projects and exhibitions, so the publics reactions and behaviors on one hand and roles/responsibility of art institutions and art professionals on the other hand develop her practices. She has worked as a university teacher, curator and writer over the past fifteen years in West Asia and Europe, and lectured in international conferences, symposiums and talks in Tehran, Singapore, Amsterdam, Vienna, and Vancouver. She is one of the co-founders of Empty Space Studio in Tehran and Vancouver.

Notes

[1] Publics and Post-Publics; The Production of the Social (January 2007), Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain, (p 5): https://onlineopen.org/publics-and-post-publics. pdf [Accessed Jan 21, 2021].

[2] al-Farabi’s Philosophy of Society and Religion (June 2016), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (Selected Aphorisms 25: 23): https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/al-farabi-soc-rel/ [Accessed June 15, 2016].

[3] Curatorial Statement, Club 29, (May 2018): http://club29.ca/modules.php?name=Menu_Items&op=show&pageid=21®ion=1, [Accessed November, 2018].

[4] Virginia Tassinari, Francesca Piredda, Elisa Bertolotti, “Storytelling in design for social innovation and politics: a reading through the lenses of Hannah Arendt”, (Design for Next; 12th EAD Conference Sapienza University of Rome, April 2017), p. 2.