Editorial | Fall 2024

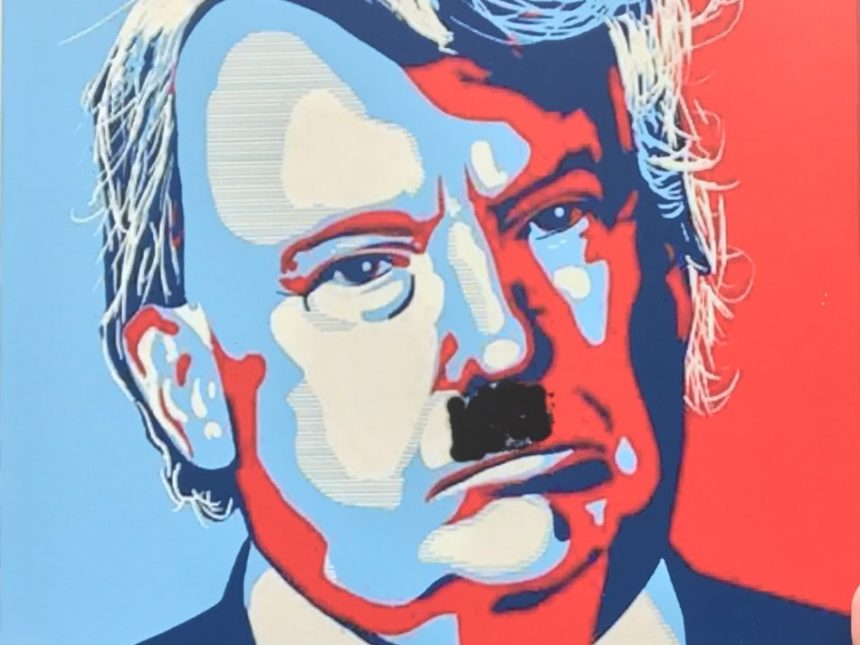

Welcome to FIELD’s Fall 2024 issue. We are publishing this issue on the cusp of a momentous presidential election, with our country poised on the brink on incipient fascism. Following the recent catastrophic hurricanes in the southeast, rescue efforts were hampered by reports of roving bands of armed, white supremacists “hunting” for federal relief workers. This is symptomatic of a much broader assault on the structures of government in the U.S., encouraged and facilitated by Donald Trump. These attacks are the logical culmination of efforts by the Republican party to dismantle forms of state infrastructure that seeks to support the broader public, beyond the mechanisms of the private market (public education and libraries, voting rights, disaster relief, workplace protections, welfare, social security, etc.). These systems of public provision were achieved through decades of working-class struggle. Beginning in the 1980s the single-minded goal of conservatives in the U.S. has been to reverse these achievements, demonize government, and “drown it a bathtub” as Grover Norquist famously observed. Driven by right wing ideologues serving at the behest of capitalist economic elites, this strategy was intended to unravel the redistribution of wealth that followed the New Deal and that was carried forward by the Great Society programs of the 1960s. Over the past four decades that redistribution has been almost entirely reversed through regressive tax policies and cuts in government programs, with $50 trillion moving from the bottom 90% of the population to the top 1%. As a result, economic inequality in the U.S. today rivals that of the Gilded Age over a century before. The economic elites who benefit from this process are able to circumvent political solidarity among the working class by appealing to the racism of white workers and pathologizing non-European immigrants through an Americanized version of Renaud Camus’ Great Replacement Theory. What the first generation of neoconservative “thinkers” were too purblind and historically ignorant to realize is that the forces they unleashed with the “Reagan Revolution” in order to enrich their donor class, led, almost inevitably, to the consolidation of a neo-fascist movement in the United States. The rise of Donald Trump marks the apotheosis of that shift, with his attacks on human “vermin,” his mobilization of SA-like gangs, his threat to unleash the military on his political enemies, his attempts to censor and control the media, and his eagerness to create internment camps for undesirable immigrants. At the same time free speech on U.S. campuses is being throttled by conservatives working to suppress dissent regarding U.S. military support for the Gaza genocide. This is, no doubt, intended to lay the foundation for a more general attack on free speech, especially at universities, should Trump return to power. Meanwhile, Elon Musk and the super wealthy are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into Trump’s presidential campaign, not in order to prevent a communist revolution that might end with them strung from a light pole, but simply because they don’t want to pay a slightly larger marginal tax rate.

This situation is hardly unique to the U.S., of course, as evidenced by the recent election of Björn Höcke, leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany, in the eastern state of Thuringia. The rise of the neo-fascist Rassemblement National party in France this year was only narrowly averted by a center/left alliance of the Nouveau Front Populaire and Emmanuel Macron’s Ensemble coalition. In this respect, France has pointed the way towards one possible response to the global rise of neo-fascism; a new “Popular Front,” echoing the original movement of the 1930s, that will bring together a broad confederation of political actors to challenge right wing authoritarianism. Over the past decade fascism has joined climate change as one of the most significant political challenges facing us today. Engaged art can play a role here, as documented by Greg Sholette’s special double issue of FIELD (Winter/Spring 2019: https://field-journal.com/category/issue-12-13/). Its role, of course, is not to serve as a singular catalyst for change, but rather, as one element within a broader mosaic of oppositional practices. The coalitional nature of a Popular Front movement requires us to move beyond the Manichean oppositions that are often encountered in contemporary left cultural theory. Here any form of resistance that fails to measure up to a prescribed model of revolutionary purity is dismissed as complicit or reformist. In the absence of any meaningful form of political action today, all that remains for art is to explore its own immanent conditions in an endless, recursive loop, modeling a properly self-reflexive criticality for future revolutionaries to emulate. In this manner, as Walter Benn Michaels’ writes, “[artistic] form in itself becomes the bearer of a class politics.”[1] The engaged art practices documented in FIELD suggest a very different paradigm. In this view we must acknowledge the necessarily pragmatic and imperfect nature of all political change, as well as its immense autopoietic potential. This doesn’t mean abandoning our ability to critically decipher processes of political appropriation and cooption, but rather, recognizing that these can be minimized, but never entirely eliminated. They must always be weighed in the balance with the contribution that any single gesture, however imperfect, might make to concrete and sustainable forms of emancipation now and in the future.

This “pragmatic” orientation, as Rodrigo Nunes argues in his essay in this issue of FIELD, allows us to multiply our efforts through collaborative interaction and alliance building, establishing “transversal relations where the composition between the two sides serves to transform them, increasing the power to act on both”. Our fall issue also features Paloma Checa-Gismero’s analysis of the various artistic and cultural interventions that were generated in response to the massive 2002 oil spill off the Galician coast of Spain. Like Nunes, Checa-Gismero points to the importance of a diversity of activist gestures. “Far from classifying and evaluating art forms as more or less appropriate in the unfolding catastrophe,” as she writes, “my hope here is to show how a multiplicity of art practices can constitute a choral ecocritical consciousness through which to document and denounce crisis, transform commonsensical narratives about our relationship to oil extraction.” This issue also features the first part of Sreejata Roy’s important analytic survey of socially engaged and public art in India, focusing on the period since the 1990s. Although often neglected in Anglophone literature, India has been an important hub of new activist and engaged art practices. The second part of Roy’s essay, based on extensive field research, will appear in our Winter 2025 issue. We are also pleased to publish Hande Sever’s interview with the Armenian artist, researcher and curator Ruben Arevshatyan. Here Arevshatyan explores the complex cultural politics of Armenia across the tumult of the twentieth century, as Armenia sought to define itself against the grain of Ottoman, Russian and Soviet imperialism. Finally, this issue includes David Guttierez’s review of Eva Marxen’s new book, Deinstitutionalizing Art of the Nomadic Museum: Practicing and Theorizing Critical Art Therapy with Adolescents (Routledge, 2020), which documents an innovative, decade long project that Marxen developed with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona (MACBA) between 1999 and 2009. Marxen was also the guest editor of FIELD #25 (Winter 2020), which was devoted to the analysis of recent engaged art practices in Latin America (https://field-journal.com/editorial/introduction-to-learning-art-and-resistance-from-the-south/). In her new book she explores the ways in which, as Guttierez writes, we might “build another political territory for Museums.” It is my hope that when the next issue of FIELD is published, we will no longer be living under the ominous cloud of neo-fascist Trumpism, or at least that we may have eluded it for a while longer as the struggle continues.

FIELD is available at: www.field-journal.com.

Grant Kester

- Walter Benn Michaels, The Beauty of a Social Problem: Photography, Autonomy, Economy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015), p.70. ↑