Fragile Infrastructures for an Art of Conviviality: Learning from documenta fifteen

Karen van den Berg

There have been few other major exhibitions in recent years that have prompted such intense fundamental debates on the social role of art as documenta fifteen curated by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa.[1] In the process, documenta not only unleashed an anti-Semitism scandal, which kept German cultural politics and German media commentary particularly breathless for months, but raised some deeper questions that will continue to preoccupy the art world for some time to come. The project-initiated discussions about morality within the art world, artistic autonomy and the limits of artistic freedom, as well as the suitability of existing institutional infrastructures for artistic practices that deviate from those which prevail in the Euro-American art history. Documenta fifteen, more than any other biennial or major contemporary exhibition before it, provided an occasion to re-consider the possibility or impossibility of a de-colonized “art world,” and the viability of the concept of the world art exhibition.[2] Remarkably, both its leading defenders and those highly critical of the exhibition, noted that after this documenta, the art world can no longer simply persist with the same set of theories and hegemonic institutional structures.[3] Any follow-up to this documenta should therefore be by no means solely about anti-Semitism, (although it would be wrong to leave out the deeper reasons for this éclat–and not only those from a specifically German perspective). It will therefore not only be a matter of appreciating this documenta and its specific contribution to a new art historical narrative. The controversies generated by this documenta also challenge us to reflect on how to overcome an overarching tendency to identify exhibited artworks–or even only parts of them–with the political positions of all exhibiting artists and the curators responsible. How, then, can the art field become a place where ways of dealing with ambiguities, contradictions, and polyphony can be practiced and rehearsed? What could an ethics of the postcolonial art world look like?

1. The “Waterloo of the Postcolonial“? [4]

Significantly, shortly before the opening of documenta fifteen, it was not an art critic, but Hans Eichel, the former German finance minister and also the previous mayor of Kassel, who raised the question of whether the Global North would be able to bear it if a collective from the Global South made the Global North the object of its own observation and determined the perspective and the standards within which it would be viewed.[5] It was already clear in the build-up to this documenta that collectives from the Global South would not only show works that dealt with the consequences of colonial rule, they would also determine the point of view, and alter the operating system of the institutional art world. The fact that the so-called global art world with its existing infrastructures was inadequately prepared for the consequences and contradictions that this entailed, and that there is still a long way to go in terms of decolonization, was made abundantly clear by this documenta edition. A certain resistance was also unmistakable to openly discussing real points of contention in the postcolonialism debate, such as the relationship between anti-Semitism and racism. Already planned discussion events were canceled again because representatives of politics, Jewish lobby groups and ruangrupa could not agree on a composition of panelists. Even before the opening, the atmosphere had become increasingly heated.[6]

The fact that a documenta that had made sociability, openness, anti-discriminatory attitudes and the reappraisal of colonial wounds its point of departure was met with accusations of anti-Semitism generated a credibility crisis that affected the entire approach. As a result, the debate about an exhibition that featured thousands of objects suddenly revolved around only a handful of works and the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Campaign) affiliation of some of the participants.[7] Even in the left-wing German daily Die Tazeszeitung, there was talk of a disastrous “Waterloo of the postcolonial.”[8]

What was initially celebrated as an innovative curatorial gesture—that is, handing over a world art exhibition to a collective from Indonesia dedicated to activist and socially engaged practices—was soon thrown into doubt by the direction of the debate.[8] Calls for a return to authorship and responsibility on the part of individuals were voiced, and collective work as a whole was quickly discredited as irresponsible and chaotic.[9] It has been argued that artistic activists could not invoke artistic freedom because they would be practicing politics and not autonomous art in the Kantian sense.[10] The polemical and often paternalistic tone of German cultural policy in particular gave the impression that the common understanding of decolonization in Euro-American art history and cultural policy entailed the incorporation of perspectives from the Global South and the showing of a larger section of ‘the world,’ which the Global North continues to make the object of its own gaze. The underlying assumption, of course, is that a universalist mission can only emanate from the West.[11] Rarely have so many voices felt called upon to speak so openly and blatantly about the loss of their own interpretive sovereignty and privilege. Peter Sloterdijk, for example, remarked: “We are observing the mobilization of a postcolonial intellectual culture. This shows how intellectuals from the periphery are getting ready to take power at the center.”[12]

Therefore, in the aftermath of documenta fifteen, we should not only talk about anti-Semitism and the frightening survival of this “negative guiding idea of modernity” [13] in the twenty first century, but rather about the contribution this edition of documenta made to the development of an alternative operating system for the arts. For there is much to be learned from documenta fifteen, precisely because it is not a simple success story. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at the conceptual side of the exhibition and examining its working approaches and their implementation more carefully in order to better understand, based on its fractures, what working curatorially on a global panorama of art production might look like. There are good reasons, especially in times of great geopolitical upheaval and planetary crises, not to abandon the project of a global perspective, as critical voices suggested, especially in the wake of this documenta.[14] It is particularly fruitful, first, to shed further light on the background of the curatorial concept and, secondly, to discuss what conclusions can be drawn with regard to the operational infrastructures and the display of socially engaged activist art forms at major exhibitions of this kind, and, thirdly, to take a closer look at how contradictory notions of the public collide here. In this way, the curatorial concept of the public sphere, including a departure from the concept of the audience, can be examined more closely.

2. Rhizomatic Curation [15]

Documenta fifteen not only set out to present a spectrum of contemporary art, beyond the author-centred Western art star machinery; the Indonesian curatorial collective ruangrupa, which developed the conceptual cornerstones for documenta fifteen, also replaced the usual organizational structure of large exhibitions with a decentered curatorial approach that was both unusual and radical in this environment.[16] Fourteen other collectives from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe were given extensive curatorial co-responsibility,[17] and were declared Lumbung Artists in a snowball system, and could, in turn, invite further artists.[18] This “voluntary relinquishment of control” was celebrated by some critics as a “welcome alternative to the fetishization of curatorial authorship” or “as a possibility not only to modify the content and look of a major exhibition, but actually to change the structures themselves.”[19] At the same time, however, decentralized curating was seen as the principal reason why the curatorial collective ultimately lacked an overview of the individual works.[20] Yet the consistency of the curatorial work in detail speaks against the latter reading, for ruangrupa aligned documenta fifteen coherently with a terminology that was implemented purposefully and was communicated successfully.

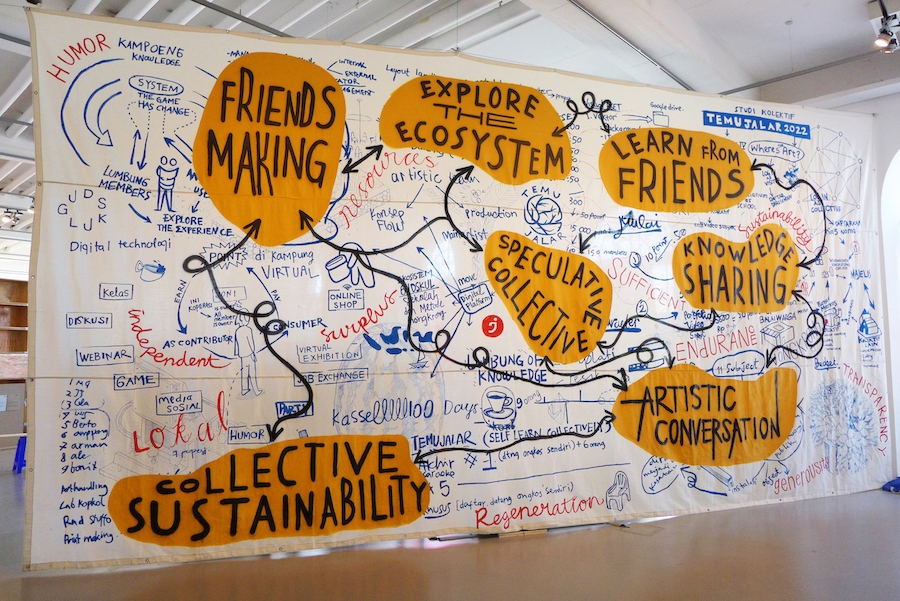

This terminology was new to the art world because it derived from the Indonesian language and an everyday cultural practice anchored there, rather than following from a widespread body of art-theoretical terminology. And at the same time, this terminology seemed eminently connectable to Western discourse. The most memorable and important term was “lumbung”. In the Indonesian language, it refers to a communal rice barn, as found in rural regions, which is used jointly by farmers to collect and store harvest surpluses and share them as common property. In their curatorial concept, which ruangrupa unfolded within the exhibition itself in wall drawings and diagrams at various locations, this term was illustrated many times. The entire curatorial and organizational logic of documenta fifteen was derived from the lumbung concept. This principle of the “collective of collectives”[21] resulted in the overwhelming number of 1,500 participating artists, some of whom said of themselves that they were not actually artists but activists, cultural workers, and community workers or even puppeteers, whereas others were quite traditional painters.

Accordingly, not everything in the exhibition was art nor did all practices follow the logic of an art exhibition. It was not always clear which objects were exhibits by individual artists and which were documentation, furnishings, educational designs, traditional folk art or workshop facilities, especially since ruangrupa as a collective of architects, artists, designers and filmmakers was itself active in design and intentionally did not differentiate between artistic and curatorial work. But this was also part of the concept. Members of ruangrupa, together with the student collective Studio 4oo2 from Jakarta, designed the corporate identity of the interlocking hands, as well as the furnishings of entire exhibition areas.[22]

What is remarkable here is that ruangrupa did not resort explicitly to terms circulating widely in the art field, such as commons, care, or multitude. Instead, the collective derived its curatorial concept by drawing-on historically rooted rural Indonesian traditions. At the same time, the anthropological concept of art anchored in traditional everyday practices exhibited a striking similarity to the terminology circulating among international curators who acquired their conceptual framework at elite European and American universities. By consistently holding on to their own terminology, ruangrupa made it clear that the concepts seen as new or novel in the Western art world, such as speaking about commons or rhizomatic structures of thought, responsibility and the social, can also be derived from and through other cultural traditions, and by no means owe their origin to Western thinking alone. It was not a matter of opposing the hegemonic Western discourse with a new particularistic concept of art, but rather of promoting a polyphonic understanding of art that has diverse roots and can also be derived from a range of other life practices and not just those from the cultural traditions of European bourgeois society. With this conceptual orientation, therefore, an attempt was made to develop an anthropologically broad concept of art, rooted in everyday practice and not fashionable art theoretical discourse. “Art is rooted in life,” ruangrupa writes in the explanatory text of the documenta fifteen handbook.[23]

In the midst of the highly competitive star system which documenta has encouraged for decades, ruangrupa therefore invited little-known collectives and artists barely anchored in the gallery system to simply do what they usually do in their local communities.[24] They were to represent artistic practices and a self-understanding whose premises for action developed in all kinds of different social constellations and fields of force outside those recognized by a Western-dominated general global art public. Another important concept that shaped the style of the documenta fifteen experience was “nonkrong”. In Indonesian, nonkrong refers to hanging out together and having time for each other.[25] Instead of focusing on individual contemplation, the focus was on decelerated togetherness. To this end, ruangrupa and various other artists association with local initiatives set up places of regeneration and gathering throughout the city, creating hangout zones, community gardens, and waterfront spaces that invited people to linger. Already in 2021, ruangrupa transformed an empty department store directly on Friedrichsplatz into a community center. With its inviting brightly painted facade, it established a space for discussion events and gatherings in the middle of the pedestrian zone long before the formal exhibition opening.[26] One of ruangrupa’s most radical curatorial decisions in this context was to transform half a floor of the venerable Fridericianum—the main documenta venue—into a lively creative playground for children and young people under the label RURUKIDS, and to use the site to bundle a series of educational projects together. Graziela Kunsch’s project Public Daycare, in particular, apparently enjoyed great popularity among the people of Kassel, so much so that an initiative to purchase it was formed after the end of the exhibition.[27]

The fact that ruangrupa did not conceive of documenta fifteen as an exhibition, but rather as what they termed an “ecosistem” was reflected, among other things, in the fact that the collective initiated a range of more or less sustainable co-operative projects with a wide variety of local initiatives well in advance—for example, with art and cultural spaces, the local boat rental, sustainability initiatives, local restaurants, local publishing houses, all the way to local radio stations and a homeless magazine in which the list of artists was published.[28] In addition to the official exhibition spaces, this led to the creation of a whole series of “accessible common spaces” in the city that were free of charge and grouped together under the umbrella term “Meydan”.[29] This makes it clear that an expanded concept of curating came into play at documenta fifteen, one that went far beyond simply making an exhibition. This concept also shows a kinship with what has been described by theorists such as Beatrice von Bismarck and others as an extended understanding of the curatorial. [30] The curatorial is described here as a relational knowledge system of its own with its own intellectual and aesthetic discourses, practices, and infrastructures. In this view performative activities such as cooking, eating, meeting, and principles of hospitality and the creation of temporary educational platforms are as much a part of the curatorial repertoire as is a notion of art that also includes political activism, journalistic research, humanitarian interventions, research on politics and ecology, social work and educational workshops.[31]

Nevertheless, ruangrupa’s ecosystem follows an episteme of its own. While in von Bismarck’s logic these practices arise from the decolonization efforts of Euro-American art theory, in ruangrupa’s case this repertoire is traced back to a popular cultural understanding of art, folk art traditions and the micropolitics of everyday life in small Indonesian communities. Therefore, from ruangrupa’s perspective, the open kitchen behind the Fridericianum, which was potentially accessible to everyone, the possibility of participating in cooking teams as a visitor, the appearance of the curators as DJs in a neighboring retail store, and the extremely relaxed and inviting atmospherewas not intended to introduce a new set of concepts into the artworld. And collective and participatory approach was not chosen to propagate a new understanding of authorship.

Ruangrupa’s approach was rather indifference to the artworld expectations and thus becomes more understandable when one realizes that ruangrupa was founded in 2000 as a non-profit organization that primarily offered video workshops and showed films.[32] During the Indonesian dictatorship under Haji Mohamed Suharto, which ended in 1998, there was only one television channel in the country. When digital cameras became available in the 1990s, a number of networks were established in Indonesia to develop their own film programming.[33] Ruangrupa was one of the oldest and most extensive of these networks, training people throughout the country to capture their own environments on film and encouraging people to counter the monopolization of image production by state television by creating their own images. In order to promote a diversity of perspectives, people also experimented creatively with images and participated in media workshops,[34] which became “effective sites at which normative ideas about national and local identity were questioned,” according to ethnologist Miguel Eschobar Varela [35]. This experimental way of working served to “break away from the aesthetic—as much as ideological—constraints of mainstream film and television.”[36]

Just as Achille Mbembe has argued that there can only be decolonization if the once colonized develop their own epistemology, ruangrupa follow the principle of taking their own epistemic traditions as a starting point.[37] Therefore, if one wants to understand ruangrupa’s rhizomatic, collective model of production and presentation, it is important that this is not defined as simply a reactive distancing from the Western concept of individual authorship or even from the concept of genius, which, incidentally, also developed in opposition to specific forms of domination and oppressive aristocratic regimes.[38] Rather, ruangrupa’s curatorial approach to work derives from its own understanding of the solidarity-based creativity of the many and from traditions of Indonesian hospitality. Added to this is the fact that their form of work emerged in a country without strong cultural institutions and infrastructures—and under the conditions of incipient digitalization. It would therefore also be a serious misunderstanding to regard runagrupa’s form of collective working as a rampant culturalism that only recognizes the collective nature of cultures, or as the “sheep bleating of cultural identities,” as the art theorist Bazon Brock did in a polemic on documenta fifteen, borrowing from Friedrich Nietzsche’s polemic vocabulary.[39] Brock, who had founded the documenta visitors’ school in 1968, believed ruangrupa’s documenta would finally bury art, because it was deliberately heading toward a re-totalization of society by collapsing the individual and the concept of subjectivity into the collective. “People liquidated art in the name of artistic freedom.”[40]

However, to view documenta fifteen as a departure from the Western principle of the individual artist fails to recognize both its claim to self-empowerment (which can also be individual) and the importance of polyphony and that in this documenta “completely different concepts of art stood side by side on an equal footing.”[41] With Indonesian terms such as lumbung and nonkrong, in fact, a terminology was introduced that made it possible to integrate such diverse approaches to art as activism, folk and avant-garde art, the visual practices of marginalized groups as well as ethnic and “neurodiverse” minorities [42], pop culture, but also touching, poetic artworks by individual artists into an astonishingly unified and largely serene, hospitable and convivial panorama, in which a very relaxed time regime alternated with violent images and the almost excessive productivity of the many.[43] Through this polyphony, any self-exoticization and any totalitarianism of a specific understanding of art was avoided. Here are a few impressions: the initiative Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture invited visitors to skater classes in a halfpipe, next to a running printing press that produced small publications, whilst on the wall was a monumental mural with scenes from Bengali cinema by the Britto Arts Trust-Collective, which had set up a vegetable garden with an open kitchen in the outdoor space, and where one hundred guest groups with migrant histories cooked on one hundred days. Spread throughout the city were small art-related creative ecotopes like the backyard near the main train station, where the Nhà Sàn Collective from Hanoi collaborated with Indonesian immigrant initiatives to create a poetic garden with typical Indonesian herbs.[44]

The Danish community project Trampoline House and the Wajukuu Art Project from a slum on the outskirts of Nairobi were among those initiatives that explicitly promoted the power of the collective, but at the same time made structural violence and the fragility of the individual tangible. The Wajukuu Art Project provided one of the most impressive installations in terms of aesthetics and content, which revolved around life under the conditions of violence and criminality present in the slums, with all its regimes of thought and feeling. It also documented how artists in the slums, in the complete absence of any formal created a community studio that evolved into an educational project for the young people in the neighborhood who had few opportunities.[45] This Kenyan collective should be singled out because it was also given a particularly prominent location within the exhibition parcours. It clad the entrance to the sleek glass architecture of the Documentahalle in rusty corrugated iron and transformed the spacious entrance into a favela-like hut entrance, thus making the whole paradox of such a major exhibition tangible. Inside, one entered a space somewhere between torture chamber and refuge with dark exhibits full of magical violence. On Friedrichsplatz, Richard Bell erected a simple tent, a replica of the “Aboriginal Embassy” set up in Australia in 1972, where people were invited to talk about identity issues.[46] The opening party on Friedrichsplatz with the Indonesian women’s band Nasida Ria and mass karaoke had more the character of a cross-cultural folk festival and had little in common with a conventional art vernissage, especially since the audience was not the usual glamorous art public.

All of this did not seem chaotic at all, but rather the product of a very consistent choreography, in which two central concerns were obviously at stake: first, to make it possible to experience the diversity of forms of life and expression from the most diverse regions of the world and the aftermath of colonial rule, and second, to enable encounters through many different gestures of hospitality. For the majority of exhibition visitors, therefore, the anti-Semitic, or the works interpreted as such, were by no means among the dominant experiences of documenta fifteen.[47] Rather there was a chance to immerse themselves in African pop culture or Armenian folk music, the possibility of rummaging through archives of marginalized groups, some of which operated with more or less unambiguous messages but others which were also translated into immersive installations open to a range of different interpretations. Lumbung curating involved an amazing attention to detail. Even the usual sponsor boards in the entrance area were replaced and artistically interpreted by the drawings of the Romanian activist Dan Perjovschi—incidentally an avowed critic of the compulsion to be collective. Through many small measures, therefore, it was possible to transform the venue—the often-considered charmless German provincial city of Kassel—into a place where one could go on sensory journeys of discovery, encountering very different familiar or foreign aesthetics, symbolic worlds and narratives.

3. Fragile Infrastructures for the Politics of Friendship

The principle of hanging out, the nonkrong, which also made it possible to meet artists such as Richard Bell or Dan Perjovschi and members of ruangrupa again and again in the city and in the ruruHaus, the visitor center with café, bookstore, and discussion forums, did not, however, align with the demand for educational programs available to large groups of visitors.[48] The informal gatherings were unable to compensate for the lack of public discussion events with adequate publicity, since only a few enjoyed the privilege of having individual conversations with the curators or participating artists. Participation in the workshops was, to an extent, reserved for insiders and persistent visitors who clicked their way through the depths of the website, registered well in advance, and were prepared to wait longer. There were, as a consequence, two distinct approaches to experiencing documenta fifteen: either the visitors regarded the event as a conventional exhibition experience, or they followed the participatory logic and also took part in the workshops, bringing with them the capacity for the time and patience required for an unusually lengthy exhibition visit. The direct juxtaposition of the traditional infrastructure of rather high-priced gastronomic offerings and classic guided tours on the one hand and home-cooked free food with informal conversations on the other, resulted in unequal and often contradictory experiences. In addition, some guides apparently felt completely overwhelmed and ended up protesting openly against their working conditions.[49] In the eyes of the guides, documenta’s “Education and Mediation” department did not take the ruangrupa concept sufficiently seriously. The guides attributed their poor working conditions not to the curators, but to the educational department of documenta itself.[50]

Overall, the impression was that the organizational infrastructure was inadequately adapted to the requirements stemming from the various forms of participatory and discourse-oriented art. Ruangrupa, who formulated their understanding of “Socially Engaged Art” in one of their conceptual illustrations and wrote that visitors “should not be there to observe but to be part of the process,”[51] were well aware that their claim contradicted the structures of a mega-event. In their accompanying book, in self-critical terms, they admitted that they would have liked to find better solutions [52]—especially since behind the slogan “make friends not art” was an understanding of the public that contrasted with what the community art researcher Doug Borwick—not entirely without disdain—called “spectator art”.[53] Instead of relying on the attention economies of the star system, documenta fifteen with its 1,500 artists operated with a kind of hyperproductivity of the many and thus fulfilled the requirements of a spectacular large-scale event in an astonishingly successful manner. By contrast, ruangrupa had a hard time to serve the structures of a Western public dominated by often belligerent mass media. The option of “wanting to learn” in this respect, which they put forward as an apologia in the face of the anti-Semitism accusation, was largely perceived as inadequate by the German public.[54] It was precisely against this background that the concept of “make friends not art” was discussed with great controversy and in many cases condemned as naïve social kitsch.[55] Oliver Marchart commented bitingly that documenta fifteen wanted to counter the great traumas, conflicts, and crises of the present with a harmonizing “diversity training”.[56]

At the same time, there were other more supportive voices. The Russian artist and activist Olga Egorova from the St. Petersburg collective Chto Delat, which has been running a School of Engaged Art for 20 years, said that she was particularly convinced by the concept of friendship because it had a new meaning for her since the spring of 2022. Since the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian military, for many activists in Russia it was no longer about resistance, but about survival. Thus, suddenly “friendship became something else.”[57] Without friends, suddenly nothing was possible. This assessment reminds us that the turn to the principle of friendship among many of the collectives that defined documenta fifteen owes much to social and political necessity, as it does for the exiled Russian artist. Artistic work under authoritarian regimes or in countries without supportive infrastructures for arts and culture requires a network of friends and mutual understanding. This friendship principle, however, does not follow a new distinctive global art fashion. It is neither “radical chic,” nor kitsch, nor an “experiment in form” designed out of the attention economies of the Western art system.[58] Collective curating and producing in befriended communities is rooted above all in artistic creation under precarious production conditions.

But what does it mean when “making friends” becomes the presiding concept of an exhibition which among artists and critics is still considered generally as “the world’s most intellectually acclaimed art venue”[59], and accordingly has a very powerful infrastructure, worth more than 42 million €, essentially financed by German public funding institutions?[60] This question also arises against the background that the art of the twenty first century has often been described as a medium that generates publicity essentially by marking conflicts and making contradictions tangible.[61] Does the principle of friendship not stand in contrast to this? Does it therefore achieve anything more than evoking amorphous communities that lack an awareness of diversity, fragility and antagonism, as well as a notion of public, resulting in art that, as Claire Bishop argued twenty years ago, would hardly be distinguishable from harmonizing leisure activities? [62] What does the principle of friendship mean, when operating under the eyes of the world public in one of the strongest art infrastructures, and how does it relate to the debates around decolonization?[63] Does friendship here, then, mean an allying of “the repressed and persecuted, the exploited and humiliated,” against others? How does it relate to the concept of fraternity, which gained enormous political importance with the French Revolution?[64] And how does the sphere of friendship relate to the public sphere, politics, and power relations? Does making friends mean more than creating dissident private spaces of refuge?

The history of Western philosophy has a long tradition of theoretical discussion on the concept of friendship, one in which this concept was also understood in a deeply political way. Hannah Arendt, for example, considered friendship to be the basic condition of every community. [65] Jacques Derrida argued that friendship is political above all because it frees itself from traditional ties such as “familial, neighborhood, national, political, linguistic and finally generic appurtenance” [66] and creates a space “where every other is equally altogether other.”[67] Ruangrupa did not develop an elaborate epistemology of friendship of their own, but their way of curating, which initially began with the invitation of five individuals from Kassel, Amsterdam, Jerusalem, and Denmark,[68] nevertheless did not rely on an abstract principle of friendship, but on the imperative of making friends, which was more important than art to them, since their slogan was: “Make friends, not art!”[69] So it was not about a meeting of the like and a collaboration between those who were already friends, but about creating new friendships. Seen in this light, with their rhizomatic, decentralized-collective way of curating, they were serious on an organizational level about an imperative of the friendship of the many. The choreography of the exhibition itself also unfolded a panorama of concerns that could be read as involving a search for possibilities of a coexistence of the diverse, a search that encounters ruptures, conflicts, and traumas, but also cheerfully offers to do one thing above all: to develop a common interest in the world and a shared reality.

4. “Dig Where you Stand”[70]

The curatorial approach that ruangrupa itself placed in the foreground of documenta fifteen centered on working with local communities. However, little attention was paid to questions about the relationship of this work to a national public sphere or to a so-called world public sphere, and to questions about how this approach relates to the simple local/global binary, as well as to the contentious terms of postcolonial debates “global justice and responsibility,” “critical regionalism,” “alter-globalization,” or civil society.[71] The curator’s approach was to work with local communities. This is another reason why ruangrupa underestimated the consequences that exhibiting works containing anti-Semitic caricatures would have, in Germany in particular, and what BDS (Boycott, Disinvestment, Sanctions) proximity means in a state-sponsored exhibition in a country, moreover, that has just decided by a narrow majority in the Bundestag to refuse state funding for artists and scientists who support the BDS movement. “In Indonesia, nobody cares much about us. The documenta, on the other hand, is almost a state affair. This magnitude should have been clear to us earlier,” ruangrupa members Reza Afisina and Farid Rakun told the Berlin Tagesspiegel.[72]

In addition to the successful work with the local communities undertaken by the group, there was also the governmental cultural-political public that financed documenta fifteen and a media public that viewed such events within different horizons. And here it played a decisive role that documenta, on the one hand, is regarded as a flagship and marketing instrument of German cultural policy and, on the other hand, that it is considered the foremost reputation machine of the global art world per se.[73] Here, it is remarkable that the latter function—in particular—has persisted to this day. Contrary to what the art theorist Stefan Germer assumed more than thirty years ago in an essay for Texte zur Kunst, it is obvious that documenta has still not completely degenerated into an anachronistic ritual in which internationally known curatorial impresarios announce the art market trends of the next season.[74] Against all the reasonable doubts that arose as early as the 1970s as to whether something like world art could ever be more than a “naïve claim” [75], a certain intellectual and conceptual thrust was able to persevere until today, also because the major exhibition reinvented itself at more or less regular intervals. Documenta fifteen was also such a reinvention—despite all the justified criticism.

The large-scale exhibition was created with the goal of reconnecting Germany with the international art world after the monstrous and murderous cultural slash-and-burn policies of the Nazi regime. Under the title “documenta–Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts“ (documenta, Art of the 20th Century)” its first edition in 1955 in post-war destroyed Kassel, not far from the East/West German border, was initiated by the Kassel painter and academy professor Arnold Bode, who himself was ostracized by the National Socialists. The art historian Werner Haftmann, author of the opus Malerei im 20. Jahrhundert (“Painting in the 20th Century”), which was long considered a standard work, was responsible for the art-historical direction and the formulation of curatorial theses at that time.[76] He, who together with Bode had a significant influence on the content of the first three exhibitions, was an apologist for a new world art jargon. The fact that he had once been a member of the SA and a strict National Socialist, and that he was probably also involved in the torture of partisans and the shooting of civilians in Italy, points at the same time to the sinister, guilt-ridden reverse side of this undertaking and the “hasty escape into the normal,” [77] as Germer called it, that it represented, because documenta soon wanted to do more than make Germany internationally compatible again.[78] It quickly grew into a claim to cultural leadership. Germany wanted to show itself as a model pupil of the Western post-war order and place the accomplished intellectual and moral turnaround in an internationally effective shop window. Haftmann’s talk of abstraction as the “world language of art” was not only a welcome contrast to the Nazi dictates on art, but also to Socialist Realism, which was considered constrained and regressive.[79] As if it were a matter of course, it was only German art historians who initially had the right to define this world art. It was not until 1972 that Harald Szeemann became the first non-German curator, and it was not until 2002, with Okwui Enwezor, that the European horizon was also abandoned and serious efforts to take a postcolonial view of contemporary art history could be discerned.[80]

This brief look at history underlines the fact that documenta was always more than a seismograph of “current art developments”[81] and that it still conceals a West German “soft-power post-war imperialism” tendency[82]. From a German perspective, it refers much more to a specifically German history than the international art community generally assumes. In this national perspective and the arrangements of this politically constituted public sphere, the concepts of hospitality and locally anchored solidarity promulgated by ruangrupa obviously could not quite take hold. The intensive work with local communities and the exemplary commitment to local initiatives failed to reach or effect this macro-political level. As intensive as the local work was, this documenta did not reflect critically on the fact that it was also driven by national interests. But the community-based approach also lost sight of the fact that—if one also wants to stand up for universalistic solidarity—it is out of the question to consider anti-Semitism as a distinct phenomenon which can be assessed differently according to cultural background and not as a murderous ideology that must be fought. These considerations make it clear that all local work is entangled in a complex conditional relationship between universalism, nation states and particularism, and that exploring this relationship is one of the great tasks of contemporary political and theoretical work, especially in light of multiple global entangled predicaments and relations of violence.

In the aftermath of documenta fifteen, a cultural studies volume was published under the title Frenemies—Antisemitismus, Rassismus und ihre Kritikerinnen (Frenemies–Antisemitism, Racism and their Critics), co-edited by Meron Mendel, documenta’s designated and then resigned anti-Semitism advisor. Here the memorable concept of “contact guilt” emerges, expressing the complete impossibility of a substantive discussion when anti-Semitism or accusations of racism are involved.[83] This contact guilt was also palpable for the artists involved; “Suddenly, we all had to fear being labeled anti-Semitic because we were in this exhibition,” as Tania Bruguera explained in an interview.[84] Such dynamics, however, have long since become general contemporary phenomena that have also gripped other cultural events and large sections of society. In any case, calls for the removal of artworks and the closure of exhibitions or the withdrawal of exhibits have long been part of the common culture of outrage, increasingly replacing antagonistic debates.[85] The argument that documenta fifteen became a scandal because it represented post-autonomous activist positions and because it included explicit political statements, whilst at the same time invoking artistic freedom and complaining about censorship, therefore misses the point—especially since the majority of the artworks exhibited at this documenta were not activist in the first place. The sculptures and drawings by Amol K Patil, for example, or the works from Atis Rezistans can hardly be categorized under this term. It would also be strange to read Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’ fabric collages and the Off-Biennale artworks as activist statements. Even in the case of those works that can be described as activist art, such as Dan Perjovschi’s drawings, part of their appeal lies in the fact that they operate with a humorous ambiguity.

This is precisely why it remains so important to insist that exhibited works of art—and even more so historical documents contained in archives—do not necessary reflect the artists positions. But the fact that ruangrupa argued in part in the same way undermined their own achievements.[86] For what was most convincing about this documenta were the open spaces for experience and encounter and the impressive polyphony. The event made it possible to experience what distinguishes activist art from political activism and what distinguishes socially engaged art from social work. Art-related social projects derive their power from the fact that they open-up spaces of possibility and operate with fictions, in so doing opening-up the social through the fictive and imaginary. This is precisely what many of the works exhibited at documenta have done—including, for example, the paintings created at Project Art Works. As an overall exhibition and as a visitor experience, this documenta was therefore such a space of possibility. And in this name, it should also be defended: by standing up for the fact that art must also be a place that can make the horror, the false, the monstrous, the magical, the violence and the images of the enemy its subject. Faux pas, scandals, and disputes are not always avoidable in this process, but they are not solved by expert panels and the intervention of politics. Therefore, paving exhibitions with trigger warnings or even introducing attitude tests for curators and artists is not a path that is recommended for self-respecting democracies.

Against this background, documenta fifteen was not a success story, but neither was it a disaster, because it refers above all to the unsettled and to work that is still to be done. It points to the fact that conventional infrastructures must be adapted if they are to adequately represent the diversity of artistic practices. And it points to work still to be done that, in addition, decolonizes the decolonization debates themselves, working to put local, national, and global entanglements in relation to each other, and from here to argue about an ethics of image regimes. On this basis, one of the great tasks of art could be to advocate for what I would like to call a non-non-contradictory polyphony and for forms of self-empowerment, and to open-up spaces of possibility for a new world-directedness, and from there to develop access points into a planetary imaginary.[87]

Karen van den Berg is Professor of Art Theory & Curating at Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen Germay since 2003 and since 2006 she is academic head of the university’s arts program. She studied Art History, Classical Archaeology and Nordic Philology in Saarbrucken and Basel. Teaching and guest residencies have taken her to the University of Witten/Herdecke, the Chinati Foundation in Texas, Stanford University and Bauhaus University Weimar, among others. Van den Berg’s research focuses on art and politics, socially engaged art, the theory and history of exhibiting, and studio research. Van den Berg is currently training coordinator of the EU-funded innovative training program, FEINART.

Notes

[1] From the countless contributions, only a few are singled out here: Amin Alsaden, “Collective Burdens: Making Room for ‘Others’,” Texte zur Kunst, Oct 17, 2022, https://www.textezurkunst.de/de/articles/amin-alsaden-documenta-collective-burdens-making-room-for-others/ [All web pages below were last accessed on June 24, 2023]; Andreas Fanizadeh, “Größenwahn und Niedertracht. Antisemitismus auf der documenta fifteen,” die tageszeitung, June 25, 2022, https://taz.de/Antisemitismus-auf-der-documenta-fifteen/!5860742/; Oliver Marchart, Hegemony Machines: documtena X to fifteen and the Politics of Biennalization (Zürich/Berlin: OnCurating/n.b.k., 2022); Gregory Sholette, “A short and incomplete history of ‘bad’ curating as collective resistance,” e-flux, Sept 21, 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/criticism/491800/a-short-and-incomplete-history-of-bad-curating-as-collective-resistance. For numerous references I thank Mirwan Andan, Simon Dethleffsen, Philipp Kleinmichel, Hadrian Mattern, Matthias Nölke , Andrew McNiven and Joachim Landkammer.

[2] Cf. Hito Steyerl, “Context is Everything, Except When It Comes to Germany,” &&&, June 4, 2022, https://tripleampersand.org/context-everything-except-comes-germany/.

[3] On ruangrupa cf. https://ruangrupa.id/en/about/; on the transformative impact of documenta cf. Saskia Trebing, “Documenta-Fazit. Zwischen den Fronten zerrieben,“ Monopol, Sept 26, 2022, https://www.monopol-magazin.de/documenta-fifteen-fazit/; and Nicole Deitelhoff et al., Abschlussbericht, https://www.documenta.de/de/news#news/3089-aufarbeitung-documenta-fifteen-gesellschafter-legen-abschlussbericht-der-fachwissenschaftlichen-begleitung-vor, 2023. Here documenta fifteen is described as a „game changer“ (p. 96).

[4] Andreas Fanizadeh, “Waterloo der Postkolonialen,“ taz, die tageszeitung June 21, 2022, https://taz.de/Andreas-Fanizadeh/!a64/.

[5] Hans Eichel, “Finger weg,“ Süddeutsche Zeitung, June 13, 2022, p. 134.

[6] Nicola Kuhn, “Zwei Documenta-Kuratoren im Gespräch: ‘Es gibt gar nicht den Wunsch, einander zu verstehen’,“ Tagesspiegel, August 28, 2022, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/kultur/documenta-kuratoren-im-gesprach-hier-hort-keiner-richtig-hin-8575561.html; ruangrupa, “We are angry, we are sad, we are tired, we are united: Letter from lumbung community”, e-flux, Sept 10, 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/489580/we-are-angry-we-are-sad-we-are-tired-we-are-united-letter-from-lumbung-community.

[7] What role Islamophobia played in these debates, and the effects of the extremely poor and partly misguided communication by the documenta in relation to the individual works deemed anti-Semitic or which included unequivocally anti-Semitic elements, as well as individual participants’ support of the anti-Israel BDS Campaign has therefore subsequently occupied a series of scholarly symposia, several investigative reports and research papers, especially in Germany—and this reappraisal is far from complete. Cf. https://www.uni-kassel.de/uni/en/aktuelles/meldung/2022/10/11/d15-forschungsprojekt-analysiert-antisemitismus-kontroverse?cHash=287706a3e5a00ee378cdd97249a5a9d3; https://www.his-online.de/veranstaltungen/veranstaltung-einzelansicht/news/encounter-documenta-fifteen-als-politisches-und-kulturelles-ereignis; https://www.hfbk-hamburg.de/en/aktuelles/kalender/kontroverse-documenta-fifteen-2-2-2023/; Christoph Möllers, “Grundrechtliche Grenzen und grundrechtliche Schutzgebote staatlicher Kulturförderung. Ein Rechtsgutachten im Auftrag der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien”, Oct 2022, https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/973862/2160112/e18f6070e3c66bde480f152719b07e63/2023-01-24-bkm-gutachten-moellers-data.pdf. The lawyer Christoph Möllers, a member of the expert commission, wrote that the terms of the offence of incitement were not fulfilled at the documenta; Alexander Fahrenholtz, “Der Bericht ist Teil des Problems,” HNA (Hessische/Niedersächsische Allgemeine), March 21, 2023, https://www.hna.de/kultur/documenta/der-bericht-ist-teil-des-problems-92160077.html; Oliver Marchart (as note 1), p. 107.

[8] Andreas Fanizadeh (as note 4).

[9] Cf. Nils Minkmar, “Solche Leute leiten die Documenta?,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, Sept 13, 2022, p). The final report on the anti-Semitism scandal speaks of a “principle of organised irresponsibility” (cf. as note 3, p 126); Patrick Bahners, “Der letzte Skandal,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Jan 23, 2023, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/gutachten-zur-kunstfreiheit-nach-dem-documenta-skandal-18621542.html.

[10] Möllers (as note 7); cf. Natan Sznaider, keynote at the symposium “Kontroverse documenta fifteen” (Controversy documenta fifteen), https://hfbk-hamburg.de/de/aktuelles/mitschnitt-kenyote-von-prof-natan-sznaider/; Aude Bertrand-Hoettcke and Matthias Kettner “Framing people’s justice. Normative Aporien des interkulturellen Dialogs über Kunst am Beispiel der documenta fifteen,” Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, 67/2 (2022), pp. 75-99.

[11] Hito Steyerl (as note 2).

[12] Tomasz Kurianowicz, “Peter Sloterdijk zum Krieg: Die Mehrheit der Menschheit bleibt indifferent oder stellt sich auf Putins Seite,“ Berliner Zeitung, June 26, 2022, https://www.berliner-zeitung.de/kultur-vergnuegen/peter-sloterdijk-nicht-jede-art-von-israelkritik-ist-antijudaismus-li.239934/

[13] Samuel Salzborn, Antisemitismus als negative Leitidee der Moderne. Sozialwissenschaftliche Theorien im Vergleich (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus 2010).

[14] Cf. Hito Steyerl (as note 2); Stefan Germer, “Documenta als anachronistisches Ritual,” Texte zur Kunst, vol. 6 (1992), pp. 49-64.

[15] The real novelty is the rhizome-like structure, writes Judith Elisabeth Weiss, “Schau der Kollektive. Entspannt euch! Die Documenta Fifteen ist ein Brennglas für kollektive Erinnerungen,” Kunstforum International, 283, (2022), pp. 66-77, p. 68. On the concept of the rhizome cf. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, (London and New York: Continuum, 2004).

[16] Gregory Sholette (as note 1).

[17] These were Britto Arts Trust, FAFSWAG, Fondation Festival Sur Le Niger, Gudskul, INLAND, Instituto de Artivismo Hannah Arendt, Jatiwangi art Factory, Más Arte Más Acción, OFF-Biennale Budapest, Project Art Works, The Question of Funding, Trampoline House, Wajukuu Art Project, ZK/U – Center for Art and Urbanistics, cf. ibid. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/lumbung-members-network/.

[18] https://booklet.documenta-fifteen.de/en/ueber/lumbung-member

[19] Christian Berger, “Das Prinzip der Umverteilung,“ Texte zur Kunst, Oct 17, 2022, https://www.textezurkunst.de/en/articles/christian-berger-documenta-das-prinzip-der-umverteilung/; translation by Karen van den Berg

[20] Cf. Jörg Hätschel, “Was sich ändern muss,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, Feb 8, 2023, p.9.

[21] David Joselit, “History in Pieces – On the Documenta,” Artform, Sept 2022, https://www.artforum.com/print/202207/david-joselit-on-documenta-15-and-the-59th-venice-biennale-88912.

[22] https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/the-visual-identity-of-documenta-fifteen/.

[23] Ruangrupa (ed.), Documenta Fifteen Handbook (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2022), p. 30; see also p.37.

[24] Ibid., p. 30.

[25] Cf. Ruangrupa, “What is Lumbung?,” asphalt magazine, Sept 2021, https://documenta-fifteen.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Asphalt_Issue_1.pdf.

[26] Cf. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/venues/ruruhaus/.

[27] Cf. https://www.kassel.de/buerger/kunst_und_kultur/documenta15/spendenaufruf-public-daycare.php. Likewise, the City of Kassel had already acquired the heritable building right to the ruru-Haus before the exhibition began. Further information on the works acquired by the city of Kassel can be found here: https://www.kassel.de/buerger/kunst_und_kultur/documenta15/index.php. I would like to thank Kassel city councillor Hadrian Mattern for these references.

[28] Cf. as note 25.

[29] https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/glossary/.

[30] Cf. Beatrice von Bismarck, The Curatorial Condition (London: Sternberg Press, 2022).

[31] Cf. Nina Möntmann, “Small-scale art organizations as participatory platforms for decolonizing practices and sensibilities,” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol.13, no. 1 (2021), pp. 1-8, p. 4.

[32] Cf. Miguel Eschobar Varela, “Ruangrupa. Experimental Video Workshops and Activism in Indonesia,” in Community Art. The Politics of Trespassing, edited by Paul De Bruyne and Pascal Gielen (Amsterdam: Valiz 2011), pp. 287-96, p. 288; The Collective Eye in Conversation with ruangrupa, Thoughts on Collective Practice pp.14f.

[33] Ibid., p. 294.

[34] Ibid., pp. 294-95.

[35] Ibid., p. 296.

[36] Ibid., p. 295.

[37] Achille Mbembe, Out of the Dark Night. Essays on Decolonization (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

[38] Cf. Jürgen Fohrmann, “Dichter heißen so gerne Schöpfer. Über Genies und andere Epigonen,” Merkur vol. 39 (1985), pp. 980-989.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Saskia Trebing (as note 3); translation by author.

[42] The term “neurodiverse” is used by the UK-based collective Project Art Works, https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/lumbung-members-artists/project-art-works/.

[43] Gregory Sholette (as note 1).

[44] This garden is still run by the Indonesian community: https://www.hna.de/kultur/documenta/gaertnerstolz-wie-in-vietnam-hier-wachsen-fast-100-exotische-kraeuter-und-gemuese-91745934.html.

[45] Cf. Eric Otieno Sumba, “Sell the Vision. Eric Otieno Sumba on Wajukuu Art Project at documenta fifteen,” https://www.textezurkunst.de/en/articles/eric-otieno-sumba-documenta-sell-the-vision/#id5.

[46] https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/calendar/embassy-talk-4/.

[47] Cf. Niklas Maak, “Abhängen lernen. Wenn alles so Lumbung wäre,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, June 18, 2022, p. 33.

[48] The documenta fifteen attracted more than 738,000 visitors, cf. https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/news/documenta-fifteen-closes-with-very-good-attendance-figures.

[50] Their poor working conditions resulted not only from the enormous impact of the anti-Semitism scandal, but also from the sheer volume of material in the art projects, which required a great deal of training. The leaders also complained about inadequate training and the ignoring of the fact that a wave of covid infection among the staff paralysed to a large extent the deployment of staff teams, especially at the beginning, and subsequently led to an accumulation of overtime; cf. Open letter, https://sobatsobatorganized.files.wordpress.com/2022/08/open.letter.sobat-sobat.18.08.22.pdf.

[51] Documenta Fifteen Handbook (as note 23), p. 29.

[52] Ibid., p. 40.

[53] Doug Borwick, Building Communities, Not Audiences. The future of the arts in the United States, (Winston-Salem, NC: ArtsEngaged, 2012), p. 35.

[54] Cf. Karen van den Berg, “Der Teufel steckt im Detail,” ZUDaily, https://www.zu-daily.de/daily/zuruf/2022/06-28_van-den-berg-der-teufel-steckt-im-detail.php.

[55] Cf. Eric Otieno, (as note 45); Robert Misik, “Radical Kitsch”, Vernunft und Exstase (blog by the author), August 25, 2022, https://steadyhq.com/de/vernunft-und-ekstase/posts/6715b553-6cce-49dc-958b-5a50bca750c2.

[56] Cf. Oliver Marchart (as note 1), p. 121.

[57] Olga Egorova and Dmitri Vilensky, “Die dunkle Seite der neo-liberalen Gesellschaft,” Kunstforum International, vol. 288 (2023), pp. 172-81, p. 175.

[58] Saskia Trebing (as note 3).

[59] Gregory Sholette (as note 1).

[60] Andreas Fanizadeh (as note1).

[61] Oliver Marchart, Conflictual Aesthetics Artistic Activism and the Public Sphere (Berlin: Sternberg Press 2019).

[62] Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (2004), pp. 51-79, p. 52.

[63] „Everyone seems to be invited to a communal »sharing« based on the ruangrupa of principle of generosity, but Jews from Israel had never been invited to share. It takes a lot of willful naiveté to believe that this is for the same circumstantial reasons why Swiss artists had not been invited” (Oliver Marchart, as note 1, p. 120).

[64] Hannah Arendt, “On Humanity in Dark Times. Thoughts about Lessing” (1959), in Men in Dark Times (New York: Harvest, 1968), pp. 3 – 31, p. 14

[65] Ibid., p24.

[66] Jacques Derrida, The Politics of Friendship, trans. George Collins (London/New York: Verso, 2005), p. 22.

[67] Ibid., pp. 297-298.

[68] Documenta Fifteen Handbook (as note 23), p. 16.

[69] Benjamin Seroussi, “Make friends, not art,” Select, October 16, 2019, https://www.select.art.br/make-friends-not-art/.

[70] Oliver Marchart (as note1), p. 120.

[71] Cf. Nikita Dhawan and Shalini Randeria, “Perspectives on Globalization and Subalternity,” in The Oxford Handbook of Postcolonial Studies, edited by Graham G. Huggan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 559-586; Stuart Hall, “The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity,” in Dangerous Liaisons: Gender, Nation, and Postcolonial Perspectives, edited by A. McClintock, A. Mufti, and E. Shohat (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), p. 173–87; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Judith Butler, Who Sings the Nation-State? Language, Politics, Belonging (London: Kolkata Seagull Books, 2007).

[72] Nicola Kuhn (as note 6).

[73] Cf. Oliver Marchart (as note 61), p. 26.

[74] Stefan Germer (as note 14).

[75] Hito Steyerl (as note 2).

[76] Werner Haftmann, Malerei im 20. Jahrhundert (München: Prestel Verlag, 1954).

[77] Stefan Germer (as note 14), p 50.

[78] In 1959, the city of Kassel and the state of Hessen founded a limited liability company to sponsor the event, which from then on took place every 4-5 years; cf. Carlo Gentile, “Der Krieg des Dr. Haftmann. Der Kunsthistoriker Werner Haftmann folterte für das NS-Regime,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, June 7, 2021, p. 9.

[79] Cf. Raphael Gross et al., documenta. Politics and Art (Munich, London, New York: Prestel 2021).

[80] Cf. Marchart (as note 1), pp. 56f.

[81] “If you couldn’t conquer the world with tanks – maybe with art?” (H. Steyerl, as note 2).

[82] Ibid.

[83] Meron Mendel, Saba-Nur Cheema, Sina Arnold, “Warum dieses Buch ein Fehler war,” in Frenemies: Antisemitismus, Rassismus und ihre Kritiker*innen, edited by Meron Mendel, Saba-Nur Cheema, Sina Arnold (Berlin: Verbrecher, 2022), pp. 9-25.

[84] Tania Bruguera, “Wir Künstler wurden nicht fair behandelt (Interview),“ Monopol, Sept 15, 2022, https://www.monopol-magazin.de/interview-tanja-bruguera-documenta-kuba-instar-antisemitismus-debatte-wir-kuenstler-wurden-nicht-fair-behandelt.

[85] Karen van den Berg and Marie Rosenkranz, “Von der Institutionskritik zur Moral Economy. Hans Haacke, Dana Schutz und eine queer-feministische Buchhandlung,” Journal of Cultural Management and Cultural Policy, vol. 8 no. 2 (2022), pp. 139-57.

[86] According to a dpa report of 4.8.2022 (reproduced e.g. on the website of “Deutsche Welle” (public broadcost abroad) August 4, 2022, https://www.dw.com/de/ruangrupa-brosch%C3%BCre-eindeutig-nicht-antisemitisch/a-62701145, the curatorial collective ruangrupa has declared the brochure “Presence des Femmes” by the Syrian artist Burhan Karkoutly to be “clearly not anti-Semitic”.

[87] This wording follows on from Bhabha’s concept of the „global or transnational imaginary” (Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London and New York: Routledge 1994), p. 205).