The Influence of Tehranian Artivism in the Public Domain: An Analytic Discourse on Graffiti

Narciss M. Sohrabi [1]

Introduction

Iran is a country that suffers from various limitations on urban art. These limitations are not only created by urban management authorities but also from property ownership rules. These rules imply that the walls of a house or a shop are the personal property of individuals. In this situation, graffiti artists have found their own solutions to resist and survive. Being on the street for graffiti is their form of resistance that includes enthusiasm, excitement, and a sense of giving identity to places that make everyday life empty of activity and motivation. In establishing the terrain for Iranian urban arts based on socio-political issues, Butler’s assertion can be re-framed that appearance and visibility serve to remark upon the meaning and value of stories marked by different socio-cultural challenges.[2] For Kate Gilmore, art has the right to be just what it is, and it has a duty to sustain and support its companion rights.[3] Gilmore raises the need for communicating issues of freedoms that have been undermined by state, inter-community, and interpersonal conflicts.

The practical role of art in reconstituting the urban sphere defines a citified culture partially, which contributes to the role of art in neoliberal urban planning. Art is an integral part of current capitalist processes that are turning the neoliberal art subject into a source of capital—as a resource for tourism and a real estate investment. However, recent research has found that arts and art establishments are less significant in gentrification processes than before.[4] Both public art and graffiti artworks used to be one of the methods of tourist attraction.[5][6]

Indeed, art’s presence in the urban space is dynamic and interactive, which conveys the complex forms of globalization, cultural hybridity, and plurality in contemporary daily life—where we experience politics. New agential forms and strategies expressing urban creativity in the form of graffiti, wall paintings, yarn bombing, stickers, urban gardening, street performances, tactical art, creative campaigns, and theatrical actions—amongst others—demand active spectatorship and have a growing impact on the renegotiation of space for new approaches to political participation.[7] Social mobilization in neoliberal cities constitutes a common theme in texts inspired by Henri Lefebvre’s 1968, Le Droit à la Ville, his colossal work on production and reproduction of urban space [8], and David Harvey’s Rebel Cities.[9] Urban creativity has a broad scope of interests from a clear “right to the city” perspective with its ecological, spatial, and ideological agenda to the struggles of civil rights as well as the fight for individual and collective freedoms. While this aspect has opened the research into recognizing street art as a genre for “political democratization”[10], the growing significance of art in social and spatial justice movements has been neglected by both art and social movement theories. Thus, the analysis of both fields remains academically insufficient. However, art in Iran is recognized to have had an essential part during the Iran Revolution in 1978-1979 as well as other movements, including the 2009 Green Movement and various reforms in different political periods.

This article seeks to investigate the role of urban art, particularly graffiti, in the social and cultural developments of Tehran, spanning from tangible public space to the virtual realm. I introduce specific examples of images on architectural walls, bridges, stairs, and in social media platforms—such as Facebook and Instagram—that expose socioeconomic and/or cultural problems. Overall, this paper explores art as a viable and valuable expression of social problems and suggests that images can create a symbolic terrain of resistance.

I selected the graffiti analyzed below by roaming through both the city and cyberspace over the past ten years, and my examination was carried out by thematically categorizing these works. It was challenging to locate graffiti artists willing to be interviewed. This difficulty is rooted in two main problems: first, in Iran, anonymity is one of the characteristics necessitated by these artists, and secondly, there is not enough security for this group to appear in the official media space. Interviews were conducted with nine graffiti artists in Tehran, each of whom was male and aged 22 to 28 years old, except for one who was over 35.

City as Canvas

In Iran, public spaces and walls are considered areas reserved for the expression of the government’s ideology, as well as several governmental and semi-governmental organizations that are responsible for implementing various artistic projects on urban walls.[11] In Tehran, the municipality is mainly responsible for arranging various periodic or religious events of urban art, including sculptures and murals.[12]

For Iranian graffiti artists, any topic that is interesting to the public qualifies as a subject worthy of graffiti creation. These artists consider every opportunity to affix their words and opinions onto the walls of the city. In this situation, the wall is a feature in stimulating emotional excitement, an emotion that can tarnish the collective consciousness through their appearance. Both during the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and more recently, the wall is an intermediary site that is located alongside both social activists and political situations. Graffiti artists who embed their work in public spaces are aware that those who see their art may be limited, sometimes only seen by those who are responsible for washing and clearing the walls, but they persist. Graffiti projects in Iran tend to focus on crises, including the environment, social issues, discrimination, child labor, women’s participation in soccer stadiums, inflation, embezzlement, and social services. Graffiti has a long history in Iran, as Divar Negareh, traditional paintings on the wall, but in its modern sense, it has been formed since less than two decades ago, and most graffiti artists are young people aged 18 to 32. The audience is important in Iranian graffiti art, and the artists respect the current norms of society, compelling a good relationship between the citizens and the graffiti.

In the first generation of Tehranian graffiti, most of the works were found in the northwest (Shahrak-e-Ekbatan) and west regions of Tehran, located on large cement walls. In my recent field study, I observed that most of the graffiti has been located in central parts of Tehran over the last five years. Throughout this period, I interviewed artists who worked exclusively in central Tehran and primarily produced mid-size graffiti. Many of these artworks highlight harmful stereotypes, poems, and anti-authoritarian slogans as a means to memorialize or remember the revolutionary period, which function as tools for the transformation of city walls into social diaries. Usually, these images are an expression of standing against everything that can be seen as a symbol of the existing world order: slogans and images that depict ongoing environmental problems, feminist phrases, and anti-authoritarian and geopolitical problems of Iran.

Graffiti as an Instrument for Self-Presentation

“The public sphere is constituted in part by what can appear, and the regulation of the sphere by appearance is one way to establish what will count as reality and what will not. It is also a way of establishing whose lives will be marked as lives, and whose deaths will count as deaths.”[13] Street art, in general and graffiti in particular, are methods of self-expression and communication practiced in the “third space”—a claim towards an alternative view of the society, in which another aesthetic order is possible, another city is possible, another encounter with differences is possible, and so another way of living is possible. But what about the artists?

Many intellectuals have ruminated on this query. Jean-Luc Nancy writes of a community founded on communication that is far more than the exchange of words or images.[14] Luke Dickens calls for an “in-between space” in which “urban inscription allows the city to become known through the bodily, rhythmic writing, and to rewrite it.”[15] Homi Bhabha speaks of a “third space” of dialogue and negotiation, a space where equality is practiced through difference.[16] From Anthony Giddens’s perspective, human identity is created in interaction with others and constantly changes throughout one’s life.[17] These writers suggest that no one has a steady identity. Rather, identity is under construction and change.[18] The membership of a person in a group has a strong influence on judgments regarding each individual.[19]

In the formulation of national strategies for the leisure of youth, the Ministry of Sports and Youth of Iran has divided the identity of young people into seven areas: religious identity, national and political identity, the influence of globalization, ethnic and linguistic difference, family affiliations, gender identity, and job identity.[20] This strategy emphasizes that the youth encompass a major segment of the urban population, which is one of the characteristics of urban life in Iran. Attempts to preserve subcultures and align with global developments are often pursued by young people in societies. Since young people are curious and often welcome new phenomena, they are more affected by this method than any other social group. As a result, youth culture can be viewed as the most affected by these approaches, leading to diverse identity formation in society.[21] Without a sense of one’s social identity—i.e., without specific frameworks that reveal similarities and differences—individuals in a community will not be able to establish meaningful and lasting relationships with each other.[22] It is from this perspective that we can insist that graffiti is a way to demonstrate our existence.

It is not possible to make Iranian graffiti without self-expression, which is associated with creativity that links the affairs of being to anything that exists. Thus, the creative self-expression of the graffiti artist, as a person whose identity is on the path to the formation, can be linked with elements in her/his society. In graffiti, the insistence of one’s “existence” is something that introduces the graffiti artist as a mediator and linker of the wall to the city. The self-expression of graffiti in Iran is accompanied by the creativity that serves the modern needs of a new life. In the early iterations of Iranian graffiti between 2006 and 2007, the presence of low-quality spray paint, lack of access to appropriate resources, and the work produced by artists who dominate this medium, and even high-speed Internet, contributed to the unique development of Iran’s graffiti culture. Owing to these factors, a particular strain of creativity is embedded in Tehran’s urban culture. This essential attempt for existence, the feeling of “being necessary” for presence on the street, and “fever” to join the hidden subculture of graffiti distinguish graffiti protests in developed countries from those of Iran. In Iran, hidden self-expression in graffiti contrasts against what it refers to in its own terms is associated with the aliases of artists. The alias here is an element that leads away from the direction of self-expression. How can you express yourself while not revealing your name? Perhaps we ought to return to the subject of identity to answer this question. Often Iranian graffiti artists take on a pseudonym aligning themselves with legendary superheroes such as Zorro, Batman, or Superman—heroes whose identities are unknown albeit popular amongst the people. In a way, secrecy is a part of their memorandum, and they consider public spaces to be protesting grounds.

Interview: The Voice of Dissent with Street Artists

In interviews I conducted with young graffiti practitioners for this study, I noticed that each artist said similar things in terms of content. Each is self-confident about their art and sees a bright future for their work. They acquit themselves from following Western artists and confronting the norms and values of society. Although graffiti works are censored in Iran systematically, it is possible to disseminate art virtually with the expansion of social networks, which helps to record these artists’ work and recognition.

Regarding the definition and history of graffiti in Iran, a graffiti artist who goes by the alias Nafir says: “In Iran, graffiti work is a hybrid technique for transferring meaning and arrangement of objects in cities. This art began from the generation of the 1980s, and those who began to start this art, consider themselves owed to this generation. I choose the subject of my graffiti works from my daily concerns, and I think that these issues are also of concern to the people.”

In interviews with other Iranian graffiti artists, they express their working conditions and characteristics. Kaveh, for example, views graffiti as an immortal art, and he exclusively relaxes by making this type of art. He says: “I need to create, and people love rising, especially artists. I try to talk to people through this art.” When I told him that graffiti art is illegal and asked him why he was doing this, he replied:

I love working on the street. I love to see my thoughts everywhere. I love to talk. Talking is something I’m interested in. I look at the walls in the streets when I am walking, rather than the other attractions. I would like to convey my thoughts in the simplest form. Graffiti is not just an art; it’s a kind of lifestyle. Unlike other artists, you are not at your home to paint just a few hours on a canvas. When you paint graffiti, the street becomes your second home, a house where both paintings and everyday events happen to you. Iran’s graffiti is full of potential and has made good progress. However, three things afflict the graffiti artists in Iran; one of them is washing their works from the walls; another is when you close the hands of graffiti artists to prevent creating their artworks; the third is that see their work as an example of Satanism and Westernization.

s.e.r.r.o.r argues that graffiti wants to talk about poverty. It wants to provide solutions to poverty alleviation. It does not want to blacken the face of society but wants to make the face of the city beautiful. “We increase the heartbeat of the city with this art,” said a graffiti artist called Qalamdar. “We add something to the wall. I want to talk to you. The wall is like a whiteboard and has no sense. I want the wall to be exposed to the audience.”

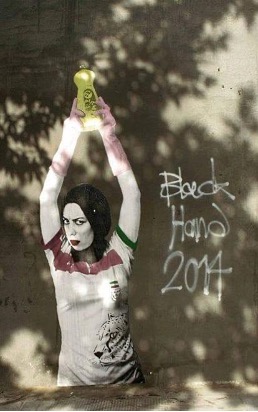

An artist named Black Hand says:

Graffiti is finally a type of urban art. I want to express the words that are not told to people. Iranian graffiti [is] not looking for erotic expression of the problems, but rather to talk about problems logically, such as the presence of women in the stadiums. Political commentary in Iran is very difficult and even harder for graffiti.

Another graffiti artist states:

Earlier, people said to me to not blacken the wall. However, the generations of the Iranian 80s and later know the structural meaning of this art. I sometimes saw an illiterate worker who reacted to an artwork, and sometimes, literate people did not. What is not expressed in mass media appears in the graffiti. Instead of saying our thoughts, we get involved in the social atmosphere, and when graffiti work is completed, people are happy about this work. Our work is an art and has a promising future in Iran, and its number is increasing, and this is due to the good things and bad things that are happening in Iran and produce concerns for the artists.

During these interviews, Iranian graffiti artists expressed their dissatisfaction with false censorship of the problems they focus their work on. Additionally, they suggested that there are many things that have been wrongly censored in Iran; many things have become taboo which should not qualify as taboo.

Graffiti in Iran, from the Streets to the Internet

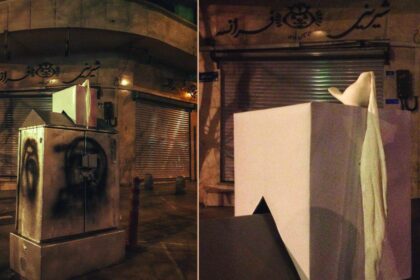

Iran’s graffiti, before its presence on the Internet, had a form of resistance to official wall paintings. The most important feature of the graffiti artists in Tehran is resistance to having a presence in the streets. The graffiti artist takes things from the city and gives something back. Like many artists, the graffiti practitioner uses a real urban context to express and influence, while large advertisements of corporations, banks, and consumer products extensively appear on billboards, wallboards, and public transport vehicles. Meanwhile, with the pervasiveness of cyberspace and the use of apps such as Instagram and Facebook with the mediation of digital cameras, graffiti has become a network that transmits the identity of these artists to cyberspace and creates a hybrid identity for them.

In graffiti culture, resistance resides in a network of relationships, the critical feature of which is the hybrid identity. Young people upload their local neighborhood subculture onto the Internet and share it in virtual networks. Iranian graffiti artists oscillate between local and global audiences. The graffiti subculture tends to be present on the street with its own signs and properties. This subculture shares itself over geographic boundaries in virtual networks. There are graffiti artists that are known by social networking apps. One of the first graffiti artists known in social networks had the alias name of Mirza Ahmad, who painted in the central neighborhoods of Tehran and abandoned spaces in a monochromatic form, which was completely different from the work of other graffiti artists. In his answer to the question of what his intent was in creating these works, he stated that: “I imagine the images of the primitive human who faces reality without any definition. At that time, scientific tools that specify the scope of everything were not available. The primitive that humans faced directly with the nature surrounding them. Such a picture takes me to the street to make all my efforts for ‘better insight.’ I seek to discover things that have been discovered earlier, and I want to express my discoveries in the virtual world.”

In the interviews, all the graffiti artists emphasized that they are thinking of Internet pages more than the street. The concept of resistance and social activity has been formed in a network of urban walls, spray paint, graffiti forms, photography, and the Internet. A resistance that, in dealing with the real world of dominant discourse, thinks about “existence.” With the presence of graffiti on the Internet as a complementary network, graffiti art has changed in shape and is not erased simply by wiping off the walls. The Internet is a medium that, in the form of a network suitable for time and space, emits another possible form of graffiti. In fact, viraffiti is another possible form of graffiti that keeps up to date. By translating graffiti to viraffiti, street art resists the city and its walls, and hybrid identities are formed based on it, a resistance that restricts the presence of city laws in daily life.[24] As a result, viraffiti is related to a hybrid identity. Whatever the reason for street art in Tehran, graffiti artists have helped to highlight the distinctions between virtual and real identities, which have changed in favor of virtual identity.

The Last Word: Concluding Remarks

“From the earliest of times—through the mediums for the externalization and expression of human longings, dreams, fears, and aspirations—explorers of creative forms have sought to offer an accounting of the best and the worst of us. This is the very same space occupied by human rights.”[25] Street art helps to highlight urban gaps and untold stories, giving a platform for the interrogation of legislations that remain ideals and not practices.

Graffiti artists form a subculture through their self-expression, which means that society does not accept them, and they depict feelings on the wall that result from this concern and an effort to find an identity. Existence in the urban space and daring to express oneself is the essential point that is raised in Iran’s atmosphere. In fact, “being afraid of the street” is replaced with “daring to go on the street.” According to the results of my interviews, it can be said that graffiti in Iran is a hybrid technique for transferring the meaning and arrangement of things in cities. Through graffiti symbolism, young people give a social aspect to their thoughts and thus distinguish themselves from the official culture. Graffiti is a way to bring your voice to others in the city. Graffiti in Iran is a form of resistance that has its own unique characteristics. The most important thing for Tehran’s graffiti artists is resistance to being present in the streets.

Narciss M. Sohrabi is an invited researcher in LADYSS. Her main research interests include public spaces, public art, and the socio-political movement of Middle Eastern societies with particular reference to modern movements when Iran engaged in different modes of socio-political exchange with the Western World. She holds a Ph.D. in Aménagement de l’espace, urbanism from Université Paris Ouest- Nanterre – La Défense, Paris, France. She has been working on Iranian public art and urban art for more than ten years. A part of her research is about graffiti and its impacts on urban public spaces. She has presented her research at national and international conferences and published part of her research in peer review journals, book chapters.

Notes

[1] Université Paris Ouest – Nanterre – La Défense-Laboratoire LADYSS-UMR7533

[2] Monica Casper and Lisa Jean Moore, Missing Bodies: The Politics of Visibility (New York: New York University Press, 2009).

[3] Kate Gilmore, “Art Rights are Human Rights,” TDR: The Drama Review 50, no. 4 (2006), pp.190-191.

[4] Carl Grodach, Nicole Foster, and James Murdoch, “Gentrification, Displacement and the Arts: Untangling the Relationship Between Arts Industries and Place Change,” Urban Studies 55, no. 4 (2018), pp. 807-825.

[5] Lindsay Bates, Bombing, Tagging, Writing: An Analysis of the Significance of Graffiti and Street Art, (Masters Thesis) (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2014).

[6] Richard Chused, “Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz,” The Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts 41, no. 4 (2018), p.583.

[7] Nicholas Whybrow, Art and the City (London: IB Tauris, 2010).

[8] Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la Ville, vol. 3. Anthropos: Paris, 1968.

[9] David Harvey, Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution (London: Verso, 2012), p. 14.

[10] Peter Bengtsen and Matilda Arvidsson, “Spatial Justice and Street Art,” Nordic Journal of Law and Social Research 1, no. 5 (2014), pp. 117-130.

[11] Narciss M. Sohrabi, “Walls and Places: Political Murals in Iran,” presented at the 4th Global Conference: Urban Popcultures (2014).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Myrto Tsilimpounidi and Aylwyn Walsh, “Painting Human Rights: Mapping Street Art in Athens,” Journal of Arts & Communities 2, no. 2 (2011), pp.111-122.

[14] Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperative Community, vol. 76. (Minneapolis,MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1991).

[15] Luke Dickens, “Placing Post-Graffiti: the Journey of the Peckham Rock,” Cultural Geographies 15, no. 4 (2008), pp.471-496.

[16] Homi Bhabha, Debating Cultural Hybridity: Multicultural Identities and the Politics of Anti-Racism (London, Zed Books Ltd., 2015).

[17] Anthony Giddens, et al., Introduction to Sociology (New York: Norton, 1991).

[18] Masoud Kosari, “Graffit as Protest art (Graffit be manzalei honar e Eiteraz),” Journal of Art and Culture Sociology, no.1 (2010), pp. 65-102.

[19] Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993).

[20] Agance Architecture Farnahad, “Report on General Strategies for Youth Leisure” by the Order of National Youth Organization (2006).

[21] Amartya Sen, “How Does Culture Matter,” Culture and Public Action 38 (2004).

[22] Asadi, “The Art of Protest, the Revolution Art”, Visual Art Journal, no. 25 (2018), pp. 18-26.

[23] He explained that Maryam Rajavi and Senator John McCain both said about the recent protests across Iran: “we stand with the protesters who demand freedom and peace!” Is it possible for an organization which claims to be anti-imperialist to be aligned with American senators who support sanctions and war against the people of Iran? Could they cooperate for peace and freedom?

[24] Philip Goodchild, “Gilles Deleuze and the Question of Philosophy,” (London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1996).

[25] Kate Gilmore, “Art Rights are Human Rights,” TDR: The Drama Review 50, no. 4 (2006), pp.190-191.