Romanticizing Reaction: Thoughts on Bouchra Khalili’s The Tempest Society

Alexis Fidetzis

As Documenta 14 entered the Athenian intellectual and artistic scene, a series of responses across a wide political spectrum generated complex rhetorics regarding the whole initiative and the validity of the dominant voice of a mega-exhibition that tries to integrate itself into a fractured political condition. Ranging from humorous to aggressive, most reactions focused on the fact that such a gesture, coming from the top, has no real potential to become part of a comprehensive cultural and social analysis, even if the people behind the exhibition were honestly interested in power structures that disseminate institutional dominance. Whether valid or not, such voices focused mainly on the institution itself and not specifically on individual artworks that, as they were created especially for this show, presented an outsider’s vision of the political and social intricacies of a country experiencing economic austerity.

Bouchra Khalili’s The Tempest Society is a visually exquisite, hour-long video piece that offers filmic portraits of different Athenians and, in order to present their life experiences as archetypal cases of perseverance against oppression, draws connections throughout space and time, linking cities and eras in a period spanning centuries. Sequestered from historical contextualization, these portraits present in a profound manner the institutionally driven oppression that many disenfranchised groups have to endure in contemporary Greece. But the creation of a historical amalgam is a dominant narrational tool of the artwork and therefore the lives of the protagonists are interlinked with the revisited heritage of the Parisian theatre group ‘Al Assifa,’ a collective of performers and activists that fought to raise muted voices against colonialism and to support immigrant labour rights in the 1970s. The video explores the legacy of the group by inserting their actions in the context of contemporary Athens, “the European economic crisis and its effect on Greece, contemporary migration and the conditions of immigrant workers and refugees.” [1]

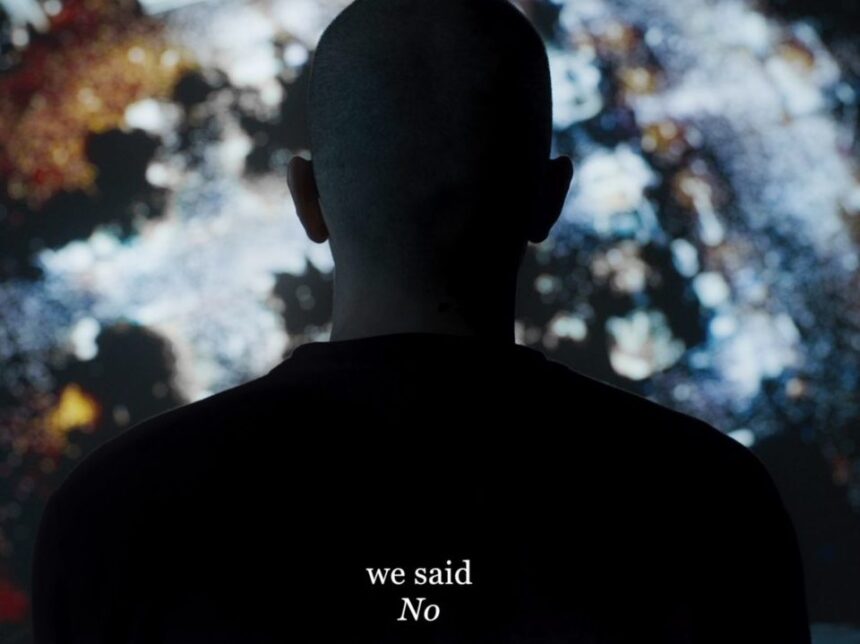

By channeling Pier Paolo Passolini’s concept of the Civic Poet, the film continues with the presentation of several acts of civil disobedience, creating parallels between a wide range of such acts that took place in Greece over the last 150 years. In a perplexing mix of different situations which–in my opinion–are clumped together disregarding the intricacies of each case, the artist presents us with the stories of the 1973 student anti-Junta riots at the Athens Polytechnic, Alekos Panagoulis’s attempt to assassinate that regime’s dictator, General Makriyannis’ request for a constitutional monarchy in 1843, the anti-austerity protests of 2011, and the crowds that celebrated the “Oxi” vote in the 2015 referendum–the last three incidents taking place in the same location, Syntagma square (Syntagma meaning Constitution) in the center of Athens, right in front of the former royal palace, which now houses the Greek parliament.

In an attempt to celebrate voices that she perceived as muted throughout history, the artist aestheticizes the acts of resistance creating a system of values under which whoever stands against authority is by definition acting on the right side of history. As one of the actors states, “the beauty of resistance is a beauty that is foreign to them”. The term “them” is used here rather vaguely, implying in a way that there is a polarity between a collective us and an obscure, powerful them in an ongoing battle between good and evil. But the ethics of aesthetics is a field that breeds complexities. To portray each act of resistance as de-facto beautiful downplays the differences between the political status quo that is targeted, alongside the real conditions of oppression that individuals experience under autocratic regimes. Relying on a romanticized image of complex and varied political conditions, the artist seems to perceive all acts presented in the film as equally significant and therefore implies that all the regimes that produced them were equally oppressive. In this manner, extreme and reactionary actions such as mob violence towards politicians, calling for the hanging of elected officials or the burning of the parliament during the period of a constitutional democracy–things that took place as part of the 2011 protests–are presented as having the same validity as people demanding the right to vote or the attempt to assassinate a torturous dictator. Moreover, such linear narratives that somehow create causality behind acts detached from one another tend to mimic the problematic modus operandi of modernist historiography and feed into a Greek national narrative of resistance that was developed in the twentieth century and embellished existing ontological and philhellenic approaches with the idea of resistance as a phenomenon that historically condenses Greek identity as such.[2] This narrative was generally perpetuated by outsiders and natives alike, during the periods of economic collapse, in a way that the crisis became a catalyst for an attempt to define Greeks as valiant protestors, regardless of their political affiliation.

But even if we take these historical projections out of the equation, this blurring of distinct political orientations that the narrative of the film perpetuates is politically problematic and creates generalizations regarding the heterogeneous crowds that were protesting in the city of Athens during the recent times of extreme austerity. It creates a polarity where a homogenized “we” is standing against the oppression of “them’’–describing both the crowds and the regime in a concrete manner, depriving the public of their individuality but, most importantly, their different demands and political theses. This reading of Khalili’s work becomes more apparent when an actor states that “freedom is not dependent on a political regime. It depends on us. If we are free, we are free forever”. For the artist, it seems that all these beautiful people need to find a common goal, meaning freedom. But if we take into account the demographics of the anti-austerity movement, their definition of freedom would be deeply differentiated.

Regarding the referendum of 2015 for example, the film becomes extremely idealized and describes the crowd that is filmed from the sky as stars and galaxies ready to erupt. But crowds are not monoliths and, especially when energized by fantasies of national independence, they tend to be politically diverse in a spectrum that also includes dangerous extremes. Therefore, while aestheticizing the protests, the artist failed to realize she was including dangerous and extreme far right groups such as the Neo Nazi party, Golden Dawn, that urged its supporters to vote ‘No’ in the referendum and had a well-documented presence on Syntagma square during that period.

In conclusion, I would like to point out that the problems identified in the film, as they revolve around issues of disenfranchisement and institutional racism in Greece and Europe, are absolutely spot on. But the narrative that the film perpetuates in its effort to evoke the idea of a radical equality through the emotional struggles of the protagonists, creates historical leaps and projections. This condition undermines the film’s visual excellence and the artist’s critique of patriotism, as it remains trapped within a Greek national narrative that was naturalized and reinforced throughout Documenta 14. As the exhibition in its entirety focused on celebrating indigenous peoples and cultural intricacies through the lens of anti-capitalist resistance, it positioned itself into spectrums of national narratives. In the case of Greece, this focus generated a flirtation with antiquity but also, as in the case of The Tempest Society, played into a particular nationalist fantasy where resistance is portrayed as an inherent characteristic of Greekness.

Alexis Fidetzis was born in Athens in 1987. He studied painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts and the Munich Kunstakademie while he got his MFA at the Pratt Institute in New York where he focused on research-based artistic practices. He got his second master’s degree on modern Greek history at the School of Philosophy in the University of Athens. He is currently a doctoral candidate at ASFA. Fidetzis uses historical research as a means of artistic creation in an effort to diagnose current social, cultural and political issues. He is interested in the institutional management of collective social trauma alongside the ways in which power structures shape our common past. For his work he has been awarded by institutions in Greece and abroad, including the Onassis and Niarchos Foundations, while his work has been presented in group and solo exhibitions in Greece, France, Germany, Switzerland and the USA.

Notes

[1] From the summary of Bouchra Khalili, The Tempest Society (London: Bookworks, 2019), in http://worldcat.org/identities/lccn-no2010000231/ , last visit 2/3/2021

[2] Nicolas G. Svoronos, Το Ελληνικό Έθνος, Γένεση και διαμόρφωση του Νέου Ελληνισμού (Athens, Πόλις, 2004).