Ascribing an advocatorial role to the work of Zambian artist Agnes Buya Yombwe

Andrew Mulenga

Introduction

This article is a modest response to the main theme of radical social resistance and collective action that might be cultivated through the visual arts albeit within a Zambian context.

Rather than focus on a specific argument, it explores some of the numerous implications of activism that can be derived from an analysis of select artworks and sites of visual arts production by ascribing an advocatorial role to the work of Zambian artist Agnes Buya Yombwe (b.1966).

In this context, some of the questions that propel this essay are: how can we read elements of radical social resistance in the works of visual artists? Is it possible that collective action can be inspired by the display and production of certain artworks? Can producers of such works be seen as activists and agents of radical social resistance and collective action?

Understanding the risk of unjustifiable generalizations and reductionism, within the context of this essay, it is proposed that resistance can take on many forms. When it is considered radical, resistance can also be argued to take on a more disruptive form, but generally, in my understanding resistance is often linked to Liberalism, that is, the purpose of liberating humankind from regressive conservatism or indeed traditionalism as it were. As much as there exists multiple in-depth theories and models on radicalism and resistance, they will not and cannot all be captured within this essay, therefore a caveat is placed herein. Similarly, collective action is a broad themed topic and as Pamela Oliver argues, while “larger empirical literature on collective action and social movements” exists, this essay does not steep into the theoretical discussion of collective action [1]. That said, the themes of radical social resistance and collective action, respectively, in one way or another lend themselves to demands for liberty, reform or some sort of pursuit for equality or ultimately universality.

The article addresses the above by proposing that the work of Buya Yombwe, is an important inclusion in a broader discussion about the role that creative practice can play in catalyzing social mobilization and transformation.[2]

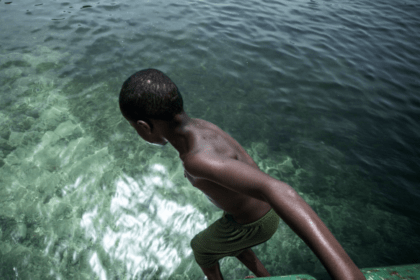

Buya Yombwe is a contemporary female Zambian artist who uses her creativity and her art to situate and address women’s experiences, influenced by her subjectivity in society. She has continuously exhibited this in her artworks as well as her own studio space—Wayi Wayi Art Studio and Gallery (fig. 1 and 2) which now serves as a cultural hub.

Who is Agnes Buya Yombwe?

Since her formative years as an artist, Buya Yombwe has consistently taken an advocatorial or radical stance in one way or another. Not only was she among the students of Martin Phiri, a young revolutionary Zambian artist and lecturer in the late 1980s, she was also part of the team that helped rally Zambian artists from across the country to form the Zambia Visual Arts Council (VAC)[3]. VAC has been the predominant governing body for the visual arts in Zambia ever since.

Following the completion of her three-year Art Teachers Diploma at the Evelyn Hone College in Lusaka in 1989, Buya Yombwe started exhibiting in local galleries and cultural centers. She wanted to see mobilization and collective action within her own visual arts contexts. “Her overriding concern was the struggle to gain credibility as an artist within a male-dominated profession. In an effort to identify other female artists working in the country and to gain support and visibility for their work, she organized workshops and seminars and spoke out on their behalf.”[4] As I previously argued, Buya Yombwe was also key in terms of the informal training of artists:

The 1990s also saw the emergence to prominence of Agnes Buya Yombwe (b.1966); she was among Phiri’s students along with Miko during the founding of VAC, when she served the council as National Treasurer. She was responsible for initiating and coordinating several Women’s Workshops and exhibitions and would later take up a residency at the prestigious Edward Munch Studio in Oslo, Norway in 1995. The contacts she established in Norway would bring about a long-standing link between Norway and Zambia, with a good number of artists following her lead and taking up studies there. Buya Yombwe is a multi-disciplined artist; a printmaker at heart, she often combines painting, sculpture, beadwork and found objects to create installations which emanate a distinctly African aura. Her aesthetic is informed by the symbolism and tenets of the Mbusa marriage rites of the Bemba people of Northern Zambia, but her themes often veer towards family life and social issues such as domestic violence, polygamy, motherhood, and women’s rights.[5]

Buya Yombwe is currently Zambia’s most eminent and emulated female artist and evidently one of the most consistent.[6] She has exhibited extensively in Zambia and abroad. She has held six solo exhibitions and has also undertaken studio residences at Wimbledon School of Art, London, United Kingdom, the Edvard Munch in Oslo, Norway in 1995 and at the McColl Centre for Visual Arts in North Carolina in United States of America in 2002. Her work is in private and public collections in Zambia, Botswana, Namibia, Norway, United Kingdom, United States of America, Germany and Indonesia.

As a school teacher, she taught art at Libala Boys and Matero Boys Secondary School’s in Lusaka for one and seven years respectively. In Botswana, she taught at Bonnington and Donga Community Junior Secondary Schools for one and three years respectively, although she lived in that country for close to a decade.

Overcoming the prohibitive costs and various layers of rigorous, bureaucratic gate-keeping in the publishing industry, Yombwe has also self-published two catalogues namely Kudumbisiana (2015) and Ni Mzilo — It is taboo (2019). These two publications respond to the epistemic gap that persists with respect to knowledge around modern and contemporary Zambian art—its chronicling, theorization and documentation—all of which might lend themselves to the many discourses around de-centering sites of knowledge production vis-à-vis books on African artists always being written in Euro-America, that is the West or global North.[7]

Buya Yombwe the artist as social and cultural activist

The bodies of work that Buya Yombwe has created over the past 13 years, (since her return to Zambia in 2007 after having lived and worked in Botswana as an art teacher), register indigenous knowledge systems as well as activism as sources of artistic reflection. Apart from family ideals, her work values and celebrates traditional values, the rights of women, children, environmental and social issues as well as good governance.

As an artist she also focuses on what she is most familiar with, namely her own experience as an educator, a wife, a mother, an influencer and mentor. She does so by effectively selecting various materials such as found objects, many of which she has horded over several years and has stored at her art studio and residence. Apart from conventional fine art materials such as acrylic, oil paints and canvas, she also uses found objects. Buya Yombwe impulsively and confrontationally exploits a wide range of media to the point that anything can be part of her creative pallet. She uses discarded plastic bottles, ash, bark, half-used firewood, seed pods, leftover cloth from a tailor’s workshop or wire, all of which she manipulates to convincingly embody her ideas.

Buya Yombwe is also a pioneer in the usage of certain materials which are only coming into use by Zambian artists in recent times. Drawing from an interview with the artist from 2000, Deborah A Hoover points out that:

Yombwe’s work differs significantly from that of her male compatriots, who are primarily concerned with landscape . . . genre themes . . . Yombwe, on the other hand combines realism, symbolism, and abstraction, and the experiments with assemblage, installation and performance art as well as painting. This choice of media is rare among Zambian artists, and it has not gone without comment. Yombwe recalls that her early assemblages of wood were labelled ‘witchcraft’ by fellow students and teachers.[8]

In her recent works she questions certain aspects of the traditional customs of her Tumbuka/Mfungwe heritage and captures the broader, sacred practices of ethnicities such as the Bemba people of Northern Zambia[9]. Her works, also lend themselves to discussion of gender issues wedged between western-inspired belief systems, traditional African belief systems and present-day urban life. Featuring quite prominently in her work are cultural referents from the Mbusa initiation rites such as its secret symbols, patterns, materials, rituals and language of which she sometimes figuratively transforms their traditional uses and places them within new, contemporary contexts that speak to current times in an urban setting[10]. The symbols of the Mbusa appear to be among her most preferred—particularly the shapes, colors and their various meanings—that allegorically move between subjective, familial dimensions and collective social experience.

The Mbusa are part of the Cisungu (or Chisungu) initiation rites of the Bemba people (her husband’s cultural group). The rites also extend to newlyweds or couples preparing to marry. It is a ritual that she underwent and influences most of her work. According to Ghurs and Kapwepwe et. al:

The Chisungu ceremony comprises of teachings through song, dance, wall and clay emblems. The Chisungu ceremony emphasizes female fertility, procreation and social etiquette. The importance of human relationships is taught alongside human interdependence with the natural environment. The colors used in these Chisungu rites are white, red and black. The clay emblems, and writings are called imbusa and are inscribed on the wall and placed on the floor of the initiation hut.[11]

The Chisungu colours of white, red and black feature prominently in Buya Yombwe’s pallet, in fact almost as a staple, as can be indicated in the various examples of her work such as Seedpod Sculpture (2012) (fig. 3) among other works.

According to Father Jean Jacques Corbeil who conducted extensive ethnographic research on Chisungu, “Mbusa means ‘sacred emblems’. These are used in the initiation ceremony of a Bemba girl when she reaches maturity. I say ‘sacred emblems’ because they are used to teach the young girl her domestic, family and social duties.”[12] The Mbusa do not only include the obligations of marriage and the duties of motherhood, but also blessings and prayers, and they are completed with symbolic purification.[13]

Nevertheless, through her art, Buya Yombwe plays an advocatorial role with regards referencing the Mbusa in that, in her own way she reinforces the resistance effected by women who preserved the essence of the Mbusa and the Chisungu before her, even during times when such rites were banned. Ghurs and Kapwepwe et al. mention this paradox when they describe how certain aspects of the ritual have survived and have been adapted to contemporary contexts:

Like many traditional rituals, the Chisungu ceremony was banned by the Catholic Church and colonial administration, and this practice was forced into secrecy for a number of decades. Much of what was taught in the Chisungu was viewed with suspicion and distaste by outsiders and appeared at odds with colonial and Christian values. But the ceremony refused to die, and women somehow managed to fit the traditional rites of the Chisungu into new social economic structures. Today, especially in urban settings, the Chisungu ceremony is perhaps one of the best examples of the interacting identities of tradition and modernity.[14]

The acts of these above-mentioned women who have over the years managed to adapt the traditional rites of the Chisungu into “new social economic structures” is a form of radical social resistance as well as one of collective action of which Buya Yombwe art is a part. Women have skillfully appropriated modern ideas into the ceremony. The imbusa clay models, as in the old days are freshly made for each occasion, but the wall emblems, which used to be painted afresh on the walls of the initiation hut for each occasion, are now conveniently on a white cloth which can be hung up flip-chart style, and folded away when no longer required[15]

The “white cloth which can be hung up flip-chart style” shows Imishintililo—the symbols that were traditionally painted on walls bear similar motifs to those that can be found at Wayi Wayi Art Studio and Gallery (fig. 4) particularly the vivid bands of zigzags in red, black and white.

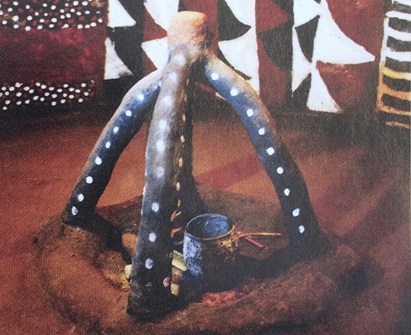

Stimulated perhaps by the earthen figurines and functional sculptures (fig. 5 and 6) she was exposed to during the rituals, Buya Yombwe effortlessly exhibits numerous fundamentals when working with three-dimensional installations. Her own performance space, a room within her art studios also exhibits sculptures and other paraphernalia that draw direct reference from the Mbusa (fig. 7).

This can also be seen in the intensity of her meticulous bead work and pointillism that is also heavily borrowed from the Mbusa motifs. Although this may seem decorative in appearance, they are in fact deeply rooted secret codes that carry messages which only initiates are able to decipher. Her exploration of the Mbusa allows her to create powerful narratives that speak to many storylines beyond her own, and this ability to transcend her own personal experiences and passionately speak to those of others is what makes her an activist.

A work that she unveiled at a solo exhibition in Livingstone entitled Stop Women Abuse (2012) creates a poignant representation of a battered woman, using just a few strips of repurposed wire, cloth and collaged wording (fig. 8). The woman’s disfigured face has been stitched-up and is depicted in a rudimentary and playful manner. The message however, is loud and clear—Buya Yombwe is advocating for an end to domestic violence. The portrait depicts a woman who is well dressed but scarred and who tries to fake a smile even amidst the harrowing ordeal of wife battery that she may be experiencing on a daily basis. In broader terms it tackles the issue of sexuality and questions women’s vulnerability in society, and reflects on socially critical issues of women’s place in society as subordinates.

Focussing on this particular image during the opening of the exhibition, the guest of honor, Brenda Muntemba (the police commissioner at the time) stated: “you have to go beyond the pictures, what I like is that she [Buya Yombwe] is talking about things we are usually ashamed to talk about, things that we want to ignore and pretend do not occur or exist. But the exhibition itself goes beyond abuse because it challenges silence.”[16] Muntemba, a strong advocate of non-violence against women during her tenure as the commissioner of police added that “we are brought-up in a culture that says it is okay to suffer abuse as a woman,” and continued by stating “sadly for us as police, one day she [the wife] will wake up on the wrong side of the bed and stab her abusive husband then for us the law will have to take its course regardless of the obvious abuse that was a build up to the final act. We therefore need more people like Agnes to come out and stop the silence.”[17] Consequently, one of the central elements in Buya Yombwe’s artwork is violence towards women and her advocacy beckons that it should not only be stopped at all costs, but women should rise up and also ‘stop’ the silence as supported by Muntemba. Cases of domestic violence should not go unreported until a point where it is too late and life is lost.

The work makes us ponder why is it that women often opt to remain in abusive relationships. By creating Stop Women Abuse Buya Yombwe assumes the role of a social activist for women’s rights and against this backdrop, her work clearly possesses an advocatory nature. This suggests that as an artist she is contributing to the role of creative practice by being a catalyst in social mobilization and transformation. Not only is her work able to reach out to important voices in society such as a police commissioner who has the power to enforce the law and mobilize change, but she is also able to communicate with the people that visit her exhibitions in public galleries such as the Livingstone Museum and Livingstone National Gallery as well as her own personal studio at Wayi Wayi Art Gallery which is also a cultural centre that conducts various types of creative workshops.

Regarding Buya Yombwe’s advocacy by means of public exhibitions as well as publications, reference can be made to her 2019 exhibition Ni Mzilo — It is taboo, that was also held at the Livingston National Art Gallery. This work investigates the subject of taboos and superstitions, but also focussed on issues ranging from environmental concerns to prostate cancer. Both the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue can be read as an inquiry and call to conversation on the curious paradox at the heart of time-honored traditions in a fast changing world. They also question certain matters of faith alongside social customs of the artist’s cultural heritage, such as the practice of Chisokoto.[18] According to the artist, she generously extracted the ‘taboos’ from personal experiences, family, friends, and the local/international community during the research phase for this accumulative body of work. She used a myriad of materials including garbage to create several installations, sculptures, collages, paintings, photographs, as well as ready-mades such as a toilet bowl.

Her work in Ni Mzilo — It is taboo can be divided into several conversations, the first being mixed media installations speaking to the advocacy of environmental awareness. Some of it comprises heaps of garbage, that was neatly aligned around a makeshift pillar and along a large window. The garbage includes everything from diapers, rusty barbecue stands, empty charcoal sacks, and those woven cages from which village chickens are sold at the marketplace. These last two items may usually be found discarded at marketplace dumpsites, but what is interesting—and this is what Buya Yombwe brings to our attention—is that they are constructed of bark fibre, which can easily be soaked, softened, and recycled. But this is not happening—whenever the contents are sold, the creators simply go back to the forest to cut down more trees. The layers of material and meaning constructed by the artist in this regard create a dynamic statement that again confirms that creative practice can play a role in catalyzing social mobilization and transformation in that the work can make its viewers think twice as they throw garbage or litter around their lived environments. Granted it is not a form of mass mobilization and may not instigate radical social resistance and collective action, but in a small way it does spark a conversation and bring awareness around environmental issues.

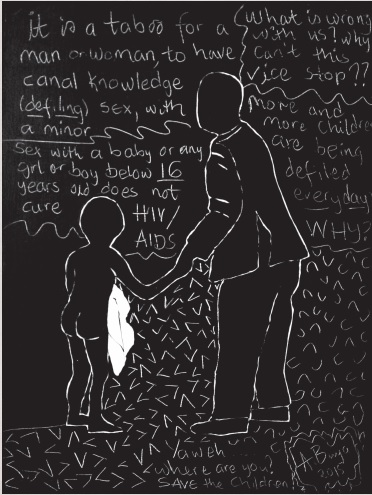

Another work from the exhibition features a series of paintings that open a wider public conversation about the plight of children. In fact, it can be suggested that these works seem more like posters than they do paintings, as all of them are enhanced with the use of text which carries very clear-cut and passionate messages. The work titled It is a Taboo to have Carnal Knowledge of a Minor (fig. 9), calls for activism against the rape of young children, particularly in certain sectors of society where it is believed that if a grown man has sex with a young child, this could cure HIV/AIDS. The painting features the simplistic outline of a man coercing a child to take off their clothes, but behind the two figures are written bold statements in the form of questions. One asks, “What is wrong with us? Why can’t this vice stop?,” while another asks “More and more children are being defiled why?” and another states “Sex with a baby or a girl or boy below the age of 16 years old does not cure HIV/AIDS.” Exhibited in a national gallery space, these expressive proclamations reshape community attitudes by beckoning the reader to do something or at least take a stance.

Taboo for Children to get Pregnant (fig. 10) is another painting that speaks to the plight of children with a focus on teenage pregnancy. Without casting particular reproach on any section of society this work merely highlights the existence of under-age pregnancy and perhaps reminds us that it does happen although it does not state whether we should or how it could be prevented.

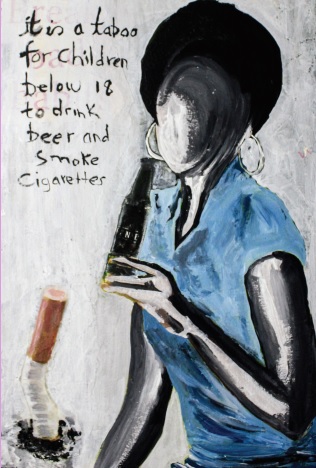

There has been an apparent increase in alcohol abuse in Zambia which has been compounded by youth unemployment but also the proliferation of cheap alcohol and cigarettes that can be bought from the make-shift corner stores in the townships. To this, Buya Yombwe responds with a work entitled Taboo for Children below 18 to Drink and Smoke (fig. 11). Here she depicts what appears to be a young woman drinking a beer. In the backdrop are the words “It is taboo for children below 18 to drink beer and smoke,” again here the artist is calling for social transformation by using her creative expression as an intervention.

While homosexuality is secretly practiced in Zambia, society does not take kindly to it. In fact, same-sex sexual activity is proscribed by Cap. 87, Sections 155 through 157 of Zambia’s penal code, where homosexual or “carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature” is a felony punishable by imprisonment for 14 years. In addition, Zambia had been declared a Christian nation by its second republican president Frederick Chiluba and ever since, Christian conservatives do not take lightly to the matter. Therefore, against this backdrop, homosexuality or rather LGBTQI+ matters are seldom spoken about in Zambia and they are often avoided almost as if the community tries to imagine it away.

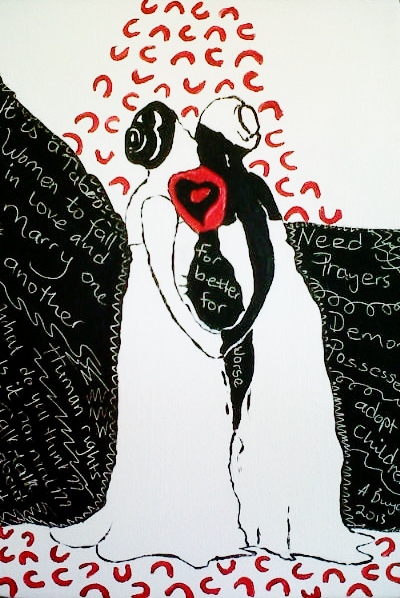

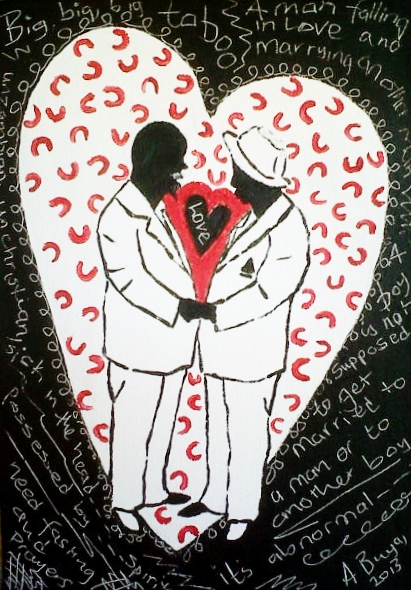

In the visual and performing arts too, the topic seems to be avoided as much as possible, not to say that it is completely sidestepped, but there seems to be an unwritten code of self-censorship. However, there are a few instances where it has surfaced in art exhibitions such as in the paintings of Buya Yombwe. While she may not be said to be an advocate for same-sex marriage or relations, her work negotiates the intricacies of these gender, or rather sexuality-based politics by motioning the public to engage in debate around the issue. In this regard, and through works such as Taboo Series Lesbian, Marriage II (fig. 12) and Taboo Series Gay Marriage II (fig. 13), Buya Yombwe’s work can be read as part of the conversation voicing LGBTQI+ concerns. Both paintings respectively depict same-sex couples kissing during western style weddings, however they are embellished with typical Mbusa motifs in the form of small C-like symbols that represent “pamo”—meaning unity, togetherness, company or most importantly, love.

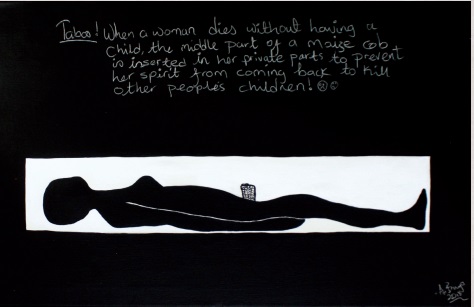

While Buya Yombwe’s work may also advocate for African culture and certain local traditions, her work is also known to challenge some of these time-honored traditions. For example, in the works Chisokoto (fig. 14) and Umufito (Charcoal) (fig. 15) she depicts the figures of women in coffins. Chisokoto bears the text: “When a woman dies without having had a child, the middle part of a maize cob is inserted in her private parts to prevent her spirit from coming back to kill other children . . .” The work can be said to argue against this seemingly barbaric custom of which is adequately explained in the text that accompanies it. Buya Yombwe can be read as being an activist who questions whether it is truly necessary to continue such practices. She perhaps sees this rite as a violation of the female body even in death, an injustice which conceivably the deceased would not have wanted to happen to them, particularly the failure to conceive or the lack of conception thereof, may not have been something of their own wanting.

‘Elephant in the room’

Ever since Buya Yombwe’s earlier mentioned exhibition Social Issues, it’s safe to argue that through her artworks she continues to explore indigenous knowledge systems such as the Mbusa, as well as engage in environmental, social-political commentary and activism that continues to question the human condition. Five years after her 2012 exhibition Social Issues, Buya Yombwe’s artworks are still challenging silence on various issues within different aspects of society. In her latest body of work exhibited during an exhibition entitled Tuning-In: Other Ways of Seeing (2019), the message in her installation of 11 paintings entitled Elephant in the room (fig. 16) was again loud and clear particularly to those within the Zambian context.[19] The phrase is a metaphorical English idiom for an important topic or problem that everyone knows about, but no one wants to discuss because it makes people uncomfortable or is socially, or politically embarrassing. Buya Yombwe’s artworks beckon the Zambian viewer not to ignore the “elephant in the room” with regards allegations of corruption among senior government officials, particularly when government continuously takes a dismissive stance towards these allegations.

Elephant in the room features silhouettes of elephants, enhanced with the use of painted text as a medium, text which carries clear-cut and passionate messages that call for conversations around many of the above issues. One of the most contentious texts reads “42 fire tenders at $42 million” (fig. 17) in reference to the Zambian governments purchase of 42 fire trucks by the state for an alleged cost of $42 million, a case that was widely known as “42-for-42” and sparked protests by some non-governmental organizations outside parliament in 2017.

Earlier that year, a report by Africa Confidential alleged that up to USD$4.7 million in aid money from Western nations had been embezzled and as a result, the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden, Ireland, and UNICEF pulled out aid from Zambia. In response, President Edgar Chagwa Lungu fired one minister and another was tried and acquitted suggesting that the current government may not truly be committed to a fight against corruption. Another painting that focuses on government’s alleged dishonesty includes text that partially reads “Natural Reserve Forest No. 27” in reference to a forest reserve that was until a few months ago, the only public protected large natural green space near Zambia’s capital. In 1957 the reserve was set up to protect the source of the Chalimbana River. Despite its importance, it has allegedly been demarcated and shared by senior government officials.

Other paintings in the series with text such as Castrate Child Defilers and Girls Not Brides address children’s rights and welfare (fig. 18). The paintings with the words “Cherish peace” and “Justice Minister Given Lubinda Clobbered by PF Youths in Kabwata” are calls for peace in the nation. Another work with the words “for the past decades and under different administrations, retirees have become destitute due to delayed payments of their benefits,” speaks for the plight of retired civil servants such as those that have been camping outside the Ministry of Justice for over 3 months. With this latest offering Buya Yombwe may be lauded for mustering the courage to touch on thorny issues at a time when public/democratic media platforms and artistic freedoms seem to be in steady decline. This is also in a context where conservativism is usually the order of the day and artists are known to shun pointed issues that may potentially land them in trouble with the authorities.

Conclusion

While Buya Yombwe’s work may be hard to empirically define as a social movement per se, it is implicit in her art production, that has the contentions of a cultural activist. This is especially important when regarding her role in terms of gender. In her formative years, art became Yombwe’s way of addressing her identity and positioning herself as a professional artist and a married woman within the context of contemporary society.[20] In her own way at Wayi Wayi Art Studio and Gallery which is open to the general public and frequently visited by school and college tours, she is actively reconceptualizing certain cultural norms and also engaging in advocacy by conducting workshops for women and youth. For example, during such workshops, participants engage in creating clay and mud sculptures (fig. 19.) that mimic traditional Mbusa sculptures (fig. 20).

At Wayi Wayi Art Studio and Gallery the artist also has a recycling shed in which she stores discarded and found objects that she repurposes to create ornamental wares (fig. 21 and 22). With these acts of recycling trash, Buya Yombwe can also be posited as an environmental activist or at least someone who is using her artistic space for social change with regards environmental awareness.[21]

Furthermore, through her art centre, Buya Yombwe claims cultural agency and formulates an artist’s intervention at the community level. As Hoover argues this affords “valuable insights into the role of art as a dynamic expression of a culture, and artists as agents of cultural change.”[22] In conclusion, again bearing in mind the risk of generalizations and reductionism, Buya Yombwe’s practice is exemplary of work “that place the woman’s voice beyond the narrow confines set around women’s lives by patriarchal society.”[23] As Ugandan scholar Amanda Tumesiime points out:

Africa needs a collective voice to speak about exploitation, challenge marginalization, and resist oppression. However, if this voice is to service a common good and qualify as truly ‘our voice of Africa,’ then its tone has to be modified to accommodate liberative voices of women. Short of this, our voice of Africa will continue to reflect the same old noises made by… selfish men, especially the power-hungry political male elite who have ruled many African states since independence.[24]

Buya Yombwe is not only one of these important “liberative voices” that Tumesiime alludes to, but her voice as an artist is also that of an agent of radical social resistance and collective action.

Andrew Mulenga is a Zambian Art Historian and a member of staff in the Fine Arts Department at the Zambian Open University in Lusaka where he lectures Art History, Philosophy of African Art in Zambia, Visual Culture and Contemporary Art Practice. He has research interests in Modern and Contemporary Zambian art, Comparative Modernities, African Futurism and the Geopolitics of Knowledge. He is also an award-winning Arts and Culture columnist (2012 CNN African Journalist of the year Arts & Culture) whose focus is documenting the contemporary art scene of his home country Zambia. He currently publishes “Mulling over Art with Andrew Mulenga”, a weekly art column in The Mast Newspaper (Zambia) and formerly published a similar column in The Post Newspaper (Zambia) from 2003 to 2016. Mulenga recently submitted a PhD thesis in Art History at Rhodes University in South Africa and holds an MA Art History from the same institution priory to this, he studied Art & Design at the Africa Literature Centre in Kitwe, Zambia. He has also conducted several art criticism/journalism workshops for emerging arts writers in Zambia. He was recently among the emerging scholars selected for the Modern Art Histories in and across Africa, South and Southeast Asia (MAHASSA) in Hong Kong and Bangladesh, organized by Cornell University, Asia Art Archives, Dhaka Art Foundation and the Getty Foundation. Mulenga is also a recipient of National Research Foundation (NRF SARChI Chair) and Andrew W. Mellon scholarships.

Endnotes

[1] (Oliver 2000: 272)

[2] (Makhubu, Castellano: 2019).

[3] See Mulenga, A. 2017, Germinating in the cracks: the identity of contemporary Zambian art, Martin Phiri (1947–1997) brought about an artistic revolution and a shift in conceptual attitudes. As a lecturer at the Evelyn Hone College returning from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing in 1987 where he had obtained a Fine Art degree, Phiri would rally his students and form the Visual Arts Council of Zambia (VAC) with the backing of the Department of Cultural Affairs. VAC would later establish its own space, an artist-run gallery which is named after Henry Tayali, a Modern Zambian Master. In 1987, Martin Phiri and his students gate-crashed a cultural policy meeting chaired by the Zambian Minister for Labour and Social Services, in an act that would redefine the destiny of contemporary art in Zambia.

[4] (Hoover 2000:45).

[5] (Mulenga 2017:71-72)

[6] Unfortunately the Zambian art scene, like many others around the world, is very gendered. In as much as one would want to avoid the mention of gender for fear of reinforcing stereotypes.

[7] (Miko; Simbao 2017: 10-14).

[8] (Hoover 2000:44-45)

[9] Sacred is used here in reference to Corbeil

[10] Mbusa means “sacred emblems,” these are used in the initiation of a Bemba girl when she reaches maturity.

[11] (Ghurs and Kapwepwe et al. 2006: 167)

[12] (Corbeil 1982:7).

[13] (Corbeil 1982:7)

[14] (Ghurs and Kapwepwe et al. 2006: 168)

[15] (Ghurs and Kapwepwe et al. 2006: 168)

[16] (Muntemba 2012).

[17] (Muntemba 2012).

[18] Chisokoto is the act of inserting a maize cob in the corps of a woman who did not bear any children.

[19] Buya Yombwe’s work was exemplary in its purpose as part of the Tuning-In: Other Ways of Seeing which served an artistic objective of political hot potato and mouthpiece for social mobilisation among other things. The 2019 exhibition “Tuning In: Other Ways of Seeing” curated by the Livingstone Office for Contemporary Arts (LoCA) and Julia Taonga Kuseka at the Livingstone National Art Gallery which opened in August and ran until December was arguably the most extraordinary contemporary Zambian art show of the year.

[20] Hoover (2000:46)

[21] There is howver a general culture of recycling by artists all over Africa and so Yombwe’s practice is not different in this regard.

[22] (Hoover 2000: 42).

[23] First Word essay for African Arts entitled “Our Voice of Africa”: It Is Less Than Our Voice Without a Woman’s Voice

[24] (Tumesiime 2018:2)

Bibliography

Yombwe, A. B.2013. personal communication, Livingstone, Zambia.

Yombwe, A. B. 2017. NIMUZILO (IT IS A TABOO), Wayi Wayi Art Studio and Gallery

Corbeil, J.J. 1982. Mbusa, sacred emblems of the Bemba, Cheney & Sons Ltd. (Banbury, Oxfordshire England

Guhrs, T. and Kapwepwe, M. 2006 (et. al) Rites of Passage – Chisungu in Ceremony: Celebrating Zambia’s Cultural Heritage, Kapwepwe, M. (Ed.) Celtel Zambia Plc, Lusaka, Zambia

Hoover, A. H. 2000. Revealing the Mbusa as art Women Artists in Zambia, African Arts, Autumn

Mulenga, A. (2012), Agnes’ ”Social Issues” condemns child, women abuse, in Andrew Mulenga’s Hole in The Wall, The Saturday Post, Lusaka, Zambia. http://andrewmulenga.blogspot.com/2012/04/agnes-social-issues-condemns-child.html

Mulenga, A. 2017b. Germinating in the cracks: the identity of contemporary Zambian art (Pages 61 to 84) in Sambia – 72 Volksgruppen bilden einen Staat: Einblicke in eine postkoloniale Gesellschaft” (Zambia – 72 ethnic groups form a state: insights into a postcolonial society) edited by Prof. Dr. Kreienbaum, M. A. and Pillmann, R. , University of Wuppertal, Germany, Budrich UniPress Ltd.

Mulenga, A. 2017a. Focus Zambia: Martin Phiri, The Man Who Changed the Zambian Art Scene in Contemporary And (C&) https://www.contemporaryand.com/magazines/the-man-who-changed-the-zambian-art-scene/

Mulenga, A. 2016 in Visual Voices, catalogue for an Exhibition of Zambian Contemporary art published by the German Embassy in Lusaka, Zambia.

Mulenga, A. 2020, ‘Elephant in the room’ in Mulling Over Art with Andrew Mulenga, The Mast Newspaper, February 5, Lusaka, Zambia.

Oliver, P. E. 1993. Formal models of collective action, Annual. Rev. Social. 1993. 19:271-300 Department of Sociology, University of Wisconsin – Madison

Simbao, R. and Miko, W. B. et. al 2017. Reaching Sideways, Writing Our Ways: The Orientation of the Arts of Africa Discourse, African Arts SUMMER 2017 VOL. 50, NO. 2

Tumesime, A. 2018. Our Voice of Africa: It is Less Than Our Voice Without a Woman’s Voice (First Word), Summer 2018, Volume 51, Number 2, African Arts Consortium: UCLA, Rhodes University, University of Florida, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.