SovereignTies: The Shared Sovereignty of Trust, Culture, and Land

Libertad O. Guerra and Angel ‘Monxo’ López-Santiago

Reacting is not deep activism; it cannot be consonant with it. Of course, sometimes we feel the urge to simply react, for we live in a world where democracy is being openly used to bludgeon democracy; a world where Brexit happened; where the Colombian peace process was voted down; where the United States is perhaps the largest post-democracy, a place where widespread corruption and white supremacism does not shock anymore. Today, the terrifying slogan “one man, one vote, one time”[1] does not simply ring crazy; it rings possible. These all, are but symptoms of long burning inequalities, and historical injustices. In urban settings, the policy path to the urbicide[2] (self-immolation) of great American cities has been in the making for decades. Yet, in troubled times activist struggles for justice cannot be zeitgeist-constrained: coherent activism is not fashion, nor should it be preeminently driven by reacting to the perceived hotness of issues at a given moment.

As we will see, land activists in New York City, and in the South Bronx specifically, are engaging in a non-reactive process of community and cultural organizing, data gathering, and investigation of the disinvestment > reinvestment > hyper-speculation > dispossession cycle to pre-empt what journalist Kevin Baker calls a “predatory monoculture.” Activists are taking the initiative, not simply reacting, by centering on land as a geography of justice. We can witness the diverse stages of this dreaded cycle of boredom in a triad of distinct enclaves that are intimately related through the Nuyorican community’s deft strategies at tropicalizing the urban space, and over a century of Puerto Rican inter-penetration through a ‘revolving door’ circular migratory flow: Loisaida/Lower East Side, the South Bronx, and San Juan/Puerto Rico.[3]

The Loisaida neighborhood, now considered the ground-zero of anti-gentrification activism in the late 70’s, demonstrated a community embarking upon the process of place-keeping that combated invisibility and social isolation through intentional acts that created a sense of belonging. Activist artists started numerous community gardens, recycling centers, and explored alternative energy sources, linking environmental issues to that of neighborhood revival. At present the gentrification process of private properties is almost complete, but the neighborhood still has a diverse population of working-class residents (43% Asian, 25% Latino, 20% White, 8% Black) in part thanks to the high concentration of New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) housing, rent-stabilization, and property titles, outcome of mutual housing, squatting, and homesteading activism.

Similarly, the South Bronx has been branded as an icon of urban blight, while simultaneously being the cradle of mambo, salsa, hip-hop, voguing, unsanctioned/sanctioned public art and street art sub-genres (sculpture, post-graffiti, conceptual outdoor work, and muralism). The area is now both still critically poor[4], and at the center of a vicious real estate feeding frenzy that threatens to ethnically cleanse its communities. South Bronx Unite—a community coalition that began as an environmental justice effort concentrating primarily around the Mott Haven and Port Morris neighborhoods in the South Bronx—developed the only mitigation and resiliency plan for the area’s waterfront. These efforts received much media visibility; while the coalition itself proved to be rather skillful in its management of both legacy and social media. This notoriety the coalition achieved was, in turn, weaponized by private developers with bad taste investing in Mott Haven[5]; as when during a meeting with local activists, Keith Rubenstein, one of the most notorious and wealthiest of the developers investing in the neighborhood, and also a notorious art-collector, thanked activists for the work they had done on behalf of Mott Haven saying—without a trace of irony—that their work had put the neighborhood ‘on the map,’ and showed people like him that the area was ‘valuable,’ as there were people passionately defending it. In 2013 the Mott Haven-Port Morris Community Land Stewards (CLT), was incorporated to ensure that community members continue to have a stake in their diverse and vibrant South Bronx community; simultaneously struggling to overcome its bad reputation, while fortifying itself against de-culturalizing economic dynamics in the face of hyper real estate speculation.

The case of Puerto Rico lies at the center of it all: the island is an actual colony (an unincorporated territory that belongs to, but it is not part of the United States); this drives what Juan González has called the “harvest of empire” to refer to how the massive growth of Puerto Rican (and other Latinx) communities in the mainland has been determined by the needs, and colonial engagements of powerful interests in the mainland. Gargantuan land grabs by American-owned industries, unemployment, political unrest, top-down industrialization, massive debt, the need for work-hands in the mainland, all of those have been reasons for migration, displacement, and the ghettoization of Puerto Rican communities in urban centers in the US.

The land-centric approach to justice is significant given the unique forms of exploitation, and the moving cartographies of resistance and solidarity, that are usually found in New York City. The effort to envision alternative land regimes, and attendant demands at cultural equity, are some ways by which socially-engaged cultural workers are challenging the (neo)colonial regimes that equally affect ancestral homelands and diasporas.

Demands for justice can be organized under three over-arching and always interrelated tropes: identitarian demands for justice, labor-centric demands for justice, and land justice demands; most contemporary demands for justice are narrated using one of these tropes (identity, labor, land). This is a heuristically useful way to organize, prioritize, and act upon a progressive agenda of inclusion, equity, and trusteeship. In the United States—except for the conveniently invisibilized land claims of Native Americans—demands for justice are almost always structured around labor and identity; land is seldom the terrain where justice is sought.

In a way, this makes sense; for it is people (not land) that suffer injustice, inequality, and racism; these issues cluster around specific demographics and classes of people. In another sense, to exclude land as the terrain where injustice happens, ignoring that these issues at times also cluster and stick—as it were—to the land, seems like a wasted opportunity[6]. There are historical reasons for this state of affairs, chief among them the fact that land speculation seems to be the United States’ favorite ‘national sport,’ but also, and perhaps more insidious, the fact that arguably we are all living on land that came to us in the most illegal and immoral way: the genocide of the Americas[7].

All over the world, but particularly in Latin America, issues around land tenure regimes have tended towards the traumatic. Land is the stuff that fuels coup d’états, revolution, military invasions, and threatens grassroots social movements. Fortunately, there is a relatively recent, and ever-growing understanding about the import of land tenure regimes as a fundamental loci of justice, and its relationship to political action in the United States, particularly in large and gentrifying urban centers. This is reflected in the growing number community land trusts (CLT), a mechanism/organizing tool that allows communities to remove land permanently from the speculative real estate market, and centers around communities imagining and building their own future development. CLTs effect empowering change in ways that are much less traumatic for communities. This is the route that a group of activists in the historically underserved POC/immigrant community of Mott Haven (South Bronx) has decided to take to address issues of equity, transparency, democratic governance, gentrification, and environmental justice; these efforts are structured as challenges to the logic of New York City’s racial capitalism.

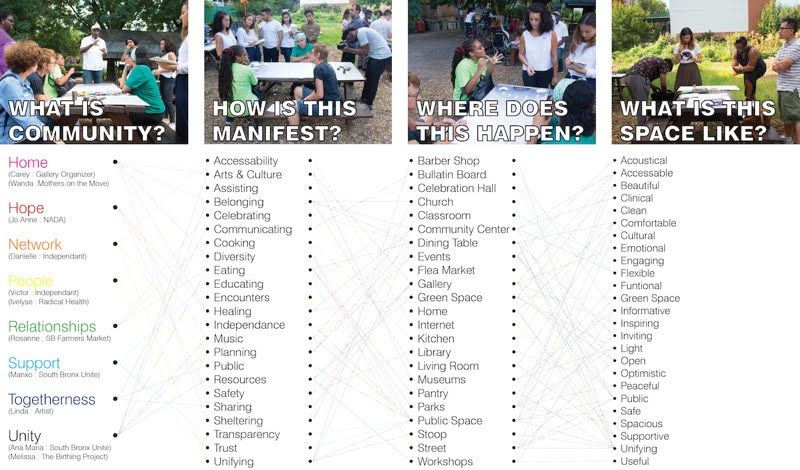

Since 2013 the South Bronx Unite founders of the Mott Haven / Port Morris Community Land Stewards (aka SBXCLT) have made cultural organizing the center of their community-building efforts. These efforts mirror similar intentions in Loisaida (LES) where the idea of forging a cultural citizenship through shared aesthetic practices is central to the 2017 Loisaida Cultural Plan. The plan advocates for a “Latinx” occupation of urban space:

To create a new urban social practice that is as much in response to urban planning, as it is in taking a defensive position against exclusion and cultural anonymity. By combining traditions and culture from the homeland and creating new forms of urban artistic expression Loisaidans survived the period of blatant disinvestment of 1970s through the 1980s. Latinx in similar situations around the City used this imaginative process to take on a new urban identity.[8]

For these activists CLTs would be about celebrating the very cultural networks that give meaning and provide joy and resiliency to entire communities. The work of these cultural activists is part of a growing New York City-wide CLT movement; and in the particular case of the South Bronx CLT, is also connected with activist grassroots movements, and CLTs (fideicomisos) in Puerto Rico. These activist ties spanning national borders is a defining feature of the CLT effort in the South Bronx and New York City.

Additionally, the destruction brought by the passage of hurricane María over Puerto Rico in September 2017 has created an ever-growing exchange between fideicomiso activists in Puerto Rico and in New York. There is a growing awareness that the debt and shock doctrine imposed on the island by its colonial authorities and the metropolis’ vulture funds, closely resembles the cycles of disinvestment in the mainland that serve as a prelude to land speculation, hyper-development, and displacement/dispossession. Diasporas have for decades dealt with this type of unnatural disaster dynamics: “neglect, conquest, displacement, vulnerability to vulture-developers, weak democratic representation, and lack of transparency.”[10]

The depth and diversity of this pool of activism is perhaps its most remarkable political characteristic; and it feels almost natural that cultural matters have become a driving and organizing force of this stewardship movement. Which, to conclude, eases us towards the idea of cultural trusts as an idea that can perhaps capture the intimate tie that binds geography with culture. It is neighborhood culture and the spirit of place (genius loci), not solely the viability of cheaper rents, that makes individual and families want to stay in their communities. People are attached to the character they helped built, that is, the neighbors that make it a living culture and the social infrastructure (as defined by sociologist Eric Klinenberg to mean spaces and organizations that shape the way people interact). Cultural erasure is the cognitive outcome of hyper-speculation, just as being displaced by high-rents and barren-land-banking by speculators, is the physical one. To ignore the phenomenon of forced migration, to reduce anti-displacement strategies to mere housing affordability, to treat families as only needing cheaper rents, is not only disrespectful, but political malpractice. Cultural workers, socially-engaged artists, and land activists need to acknowledge that land issues are part of a struggle to preserve and nurture the cultures that habitate geographies.

Monxo López is a political scientist, cartographer, musician/composer and South Bronx-based environmental activist. He teaches Latino and ethnic politics at Hunter College, Monxo is also a founding member of South Bronx Unite and a board member of the Mott Haven/Port Morris Community Land Stewards, the local Community Land Trust. He holds a Ph.D. from CUNY’s Graduate Center, and an MA from Université Laval in Québec, Canada. His academic research revolves around spatiality, mapping, social justice, political theory, and Latino communities. His cultural criticism has ranged in publications from Dia Art Foundation to 80 grados, his text/sound collaborative projects have been published by Bilingual Press and Ediciones Callejon, his political writings on spatial and social justice have been published in Salon.com, LatinoRebels, and NACLA, among other media outlets; his activist work has been profiled by The New York Times, UrbanOmnibus, and Corriere della Sera.

Libertad O. Guerra is an anthropologist, curator, and art historian. Since 2014, she has served as Director and Chief Curator of the Loisaida Inc. Center, where she has developed a new inter-generational roster of programs that explores the cross-currents of how art and place is produced and consumed in a way that does not erase one group or another. She produced critically- and community-acclaimed exhibitions; revamped the historical Loisaida Street Festival, adding a depth of cultural offer in street theater and performance art platforms for emergent and mid-career artists and tripling is attendance numbers to 30k. Her academic research and symposia has focused on Puerto Rican, Latinx, and NYC’s social-artistic movements and cultural activism in im/migrant urban settings. Her publications include essays in The Journal of Aesthetics and Protest and in the edited volume New York-Berlin: Kulturen in der Stadt. She has organized numerous local and international exhibitions, panels, and conferences, among them ¡Presente! The Young Lords in New York at Loisaida Inc. Cultural Center (2015). Guerra is a longtime resident of the South Bronx, where she is a co-founder and serves on the board of the Mott Haven/Port Morris Land Trust and advocates for environmental justice and cultural equity. She is part of the Art Against Austerity working group with Social Practice Queens, and serves as Board Chair of The Clemente Soto Velez Cultural Center in the Lower East Side.

Bibliography:

Bagchee, Nandini. 2017. “Design and Advocacy in the South Bronx”. Urban Omnibus. May 3, 2017. Accessed July 13, 2018. https://urbanomnibus.net/2017/05/hearts-studio/

Baker, Kevin. 2018. “The Death of a Once Great City.” Harper’s Magazine, July 2018. Accessed July 13, 2018. https://harpers.org/archive/2018/07/the-death-of-new-york-city-gentrification/

Hobbs, Allegra. 2018. “Gentrification’s Empty Victory”. The New York Times, June 1st, 2018. Accessed July 13, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/01/nyregion/fight-over-charas-community-center.html

Lipsitz, George. 2011. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia: Temple UP.

Loisaida Center. 2017. “Loisaida Cultural Plan”. Accessed July 13, 2018. http://loisaida.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Loisaida_Cultural_Plan_for_Public_Rollout_2017.pdf

López, Monxo. 2017. “Decolonize the Caribbean”. NACLA, October 19, 2017. Accessed July 13, 2018. https://nacla.org/news/2017/10/19/decolonize-caribbean

Pierson, Christopher. 2013. Just Property: A History in the Latin West. Volume One: Wealth, Virtue, and the Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raven, Rakia. 2016. “Who benefits from Public Land in the Bronx”. Dissent. May 25, 2016. Accessed July 13, 2018. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/south-bronx-unite-freshdirect-environmental-justice-land-trust

Urban Omnibus. 2018. “Community Land Trusts”. Accessed July 13, 2018. https://urbanomnibus.net/2018/01/community-land-trusts/

Notes:

[1] As in a man—not a woman—votes only once (for the last time) because this is the democratic election when democracy is abolished, and there will be no more voting in the future. This was a slogan used by the Islamic Salvation Front in Algeria during the 1992 election, they won. The elections were annulled, the start of a ten year long, and bloody civil war.

[2] Urbicide is a term coined in 1963 by Michael Moorcock, and popularized by author Marshall Berman. See https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/emerging-from-the-ruins)

[3] Loisaida is the way that the local Puerto Rican residents of the area began referring to the Lower East Side around the 1970’s; it is a linguistic ‘appropriation’ of the ‘Lower East Side’ into Spanish; but it is also an emblematic example of Nuyorrican Spanglish. Today most Latinx residents of the area -not only Puerto Ricans- use Loisaida to refer to the neighborhood. The word was immortalized in the foundational poem ‘Loisaida’, by one of the early figures of the Nuyorrican literature movement: the local poet Bimbo Rivas.

[4] More than a third of all residents in the area, and around 50% of those under 18 live in poverty in Mott Haven, for example.

[5] In the Fall of 2015 Somerset Partners and the Chetrit Group bought a parcel of waterfront land for $58 million dollars, three years later they sold the land—still undeveloped—to Brookfield Development for $165 million.

[6] See (Lipsitz 2011).

[7] Christopher Pierson (2013, 1) quotes from William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England: “Pleased as we are with the possession, we seem afraid to look back to the means by which it was acquired, as if fearful of some defect in our title.”

[8] See http://loisaida.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Loisaida_Cultural_Plan_for_Public_Rollout_2017.pdf

[9] As we have written elsewhere: “the few success stories of neighborhood protection and resistance to environmental racism that we know about have been possible only through these intra-diasporic horizontal networks of solidarity and concern that the diverse diasporas have developed between each other”. See López, Monxo. 2017. “Decolonize the Caribbean”. NACLA, October 19, 2017. https://nacla.org/news/2017/10/19/decolonize-caribbean

[10] Ibid.