Japanese Art Projects in History

KAJIYA Kenji

Introduction

The purpose of this essay is to critically examine the non-museum-based art project in Japan in a historical perspective.[1] The “art project,” known in Japanese as “āto purojekuto”—a transliteration of the English words—has constituted a major category in Japan’s art world since the 1990s. The term chiefly denotes art exhibitions, but includes performances, workshops, and social practices that take place in buildings other than museums or in the open air in the city and countryside. It covers a wide range of operations from large-scale exhibitions organized by local governments to moderate-size projects organized by non-profit organizations to small-sized artist initiatives. Although some of them overlap with international art biennials and triennials, art projects are mostly low-budget activities that feature domestic artists at provisional venues for experimental purposes. There have been few scholarly studies on the topic. The recent publication of two important books is changing the situation, although they both focus on the present state, rather than history, of art projects.[2] This essay will thus examine the historical contexts in which art projects have taken shape in Japan, paying special attention to the history of outdoor exhibition in postwar Japan and the introduction of art trends from overseas. The phrase “art project” seems to be becoming less frequently used these days. With its rising global popularity, socially engaged art has entered the Japanese art vocabulary as a phonetically transliterated phrase, “sōsharī engējido āto,” which is replacing the term art project despite many differences between them.[3] A pejorative term, “chiiki āto (local art),” is also attracting recent attention and emphasizes the provincial context of art projects.[4] But neither a new key term introduced from overseas nor the emphasis on regional location seem to grasp the gist of art projects. This article will thus explore Japan’s art projects in a historical perspective and consider them in relation to past overseas trends to explicate the phenomenon of the non-museum-based artistic activities as they have prevailed over the last 30 years in Japan.

Weak Social Awareness of Art Projects

I would first like to address the existing discourse on art projects among key critics and scholars. In the late 1990s, the Document 2000 Project, a non-profit project led by arts professionals and specialists in corporate patronage of the arts, was organized to support and promote art projects, and in 2001 the group published a book which might be the first concerted academic attempt to describe them.[5] In an essay entitled “Art Projects Go ‘Beyond the Museum,’” MURATA Makoto, an art journalist and project member, writes that an art project is a site-specific, ongoing activity run by a non-profit organization, that involves many volunteers. Although cursorily, he further delineates the ways in which “movable” artworks in museums are being replaced by “immovable,” site-specific art works, which prevail in art projects. Murata thus emphasizes that the art project is a new form of art initiative that engages with various people in society outside the context of museums.[6]

A more recent attempt to come to grips with the art project is a comprehensive study organized and edited by KUMAKURA Sumiko, director of Toride Art Project and professor at Tokyo University of the Arts. She articulates the art project’s social role, by pointing to its “interest and engagement with social fields outside art” as one of its characteristics. Kumakura, however, does not parallel Japanese art projects with socially engaged art in other countries. Instead, she highlights a difference with socially engaged art in other countries, namely, that in Japan “there are few artworks and activities that assert clear political messages or socially critical views” or that “present a clear social mission.”[7] She argues that people should take the situation positively, maintaining that “art projects aim to engage the majority of people whose social awareness is comparatively unformed.” Questionably, Kumakura attributes the weak social awareness to the political climate: “an aversion to discussing politics in Japan and a desire to maintain an equivocal attitude toward political and civic movements.”[8] It is true that there are many artistic practices with weak social engagement in Japan but Kumakura plays down the fact that the climate is historically constructed and countered by many social practices from realist paintings against the U.S. military bases in the 1950s to the art of post 3.11 anti-nuclear movements in the 2010s. What I argue that we have to do is to examine with greater historical specificity what situations and processes have fostered this type of weak social awareness in Japan’s art projects, without resorting to the hasty generalization.

FUJITA Naoya, a science fiction and literary critic, takes a much more critical stance towards this weakness of Japan’s art projects. According to Fujita, it is a degradation of radical artistic practices such as those shown at exhibitions like “When Attitudes Become Form” in 1969. Calling art projects “zombies of the avant-garde,” Fujita insists that artists and curators who used to be avant-garde are now content to be involved in regional revitalization with grants and subsidies given by local governments.[9] Fujita regards the weak social awareness not so much as the character of Japanese people, as Kumakura argues, but rather as the consequence of the international avant-garde’s domestication in Japan. We can see, though, that Fujita’s reference to Harald Szeemann’s legendary 1969 show is not sufficient. There are key moments to be examined in terms of historical influences between 1969 and the present which his account skips over. In fact, Japanese art projects manifested themselves in direct relation to a couple of overseas art trends in the 1980s, something which critics and scholars have missed so far but which I will discuss below.

Key critics and scholars regard art projects as activities that take place outside the context of museums. They argue that the projects are socially minded but that their social awareness is weak, which distinguishes Japanese art projects from socially engaged art in other countries, also often made independently from museums. What is important to note, however, is that this feature of Japanese art projects took shape before the introduction of socially engaged art discourse to Japan in the mid-2010s, so the urge to compare may be a bit misleading. That is why we need to go back into history to understand why Japanese art projects have become what they are today.

History of Outdoor Exhibitions

To consider the development of how social awareness appears in art projects, it is useful to look at the history of outdoor exhibitions in Japan, something that contributed greatly to the emergence of art projects.[10] Among the earliest attempts at displaying art works outdoors are those of the Gutai Art Association and the Group Kyūshū from the mid-fifties. Importantly, these artists did not choose to work outdoors as a critical response to the neutral spaces at museums and galleries but rather in pursuit of the relationship with the audience. In the 1950s, modern art museums in Japan looked mostly to Western art and scarcely dealt with domestic contemporary art at all. Contemporary Japanese artists’ works were mostly shown at the rental exhibition spaces of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum under the auspices of artists’ associations (the dantai that Reiko TOMII discusses in her essay), or at galleries, most of which were rental galleries which artists themselves could book to show their works if they wanted. Artists went outdoors so that their works could be seen in the open air by more people, beyond the expected audience who would be attracted to shows in rental spaces at museums and galleries.

Outdoor activities became more conspicuous in 1960s avant-garde art, including what art historian KuroDalaiJee (KURODA Raiji) calls “anti-art performances,” a form of radical performance pioneered by Group Kyūshū, which tended to center on the annual Yomiuri Independent exhibition in Tokyo and, after its cancellation in 1964, spread to many other locales.[11] Artists and artist collectives such as Zero Dimension and ITOI Kanji are some representatives of this kind of performance practitioner. It is true that they were intensely provocative and exhibited radical subversive power against conventions and institutions such as codes of public decency and the art world, and that there are some art works that are engaged with political issues, such as Hi Red Center’s Campaign for the Promotion of Sanitation and Order in the Capital (a performance that satirized the process of gentrification in preparation for the Tokyo Olympics in 1964). But these are relatively few in number; they were not so much rebels against exhibition spaces at museums and galleries but rather, as KuroDalaiJee argues, an anarchist disturbance of cultural and social systems in general.[12]

These practitioners were active at the same time as other avant-garde art movements, like the ones addressed in Tomii’s essay, which organized independent-style exhibitions in remote locations in an attempt to create exhibition spaces different from museums or galleries. The Contemporary Art Outdoor Festival held in the national Children’s Country Theme Park in Yokohama in 1970, however, brought an end to the popularity of non-museum-based independent exhibitions.[13] This festival was a large exhibition, with 159 artists in total, organized by a group of artists. But the show became controversial when park staff removed and destroyed more than ten politically charged artworks without the artists’ agreement. It made artists recognize how difficult it was for them not only to organize large-scale exhibitions outside museums but also to deal with political issues in public spaces.

The 1970s saw a proliferation of public sculpture installation projects called “Town Development with Sculptures” which were enacted by local governments throughout the country, placing a vast number of sculptural pieces in station plazas, parks, and around public buildings, as will be discussed later.[14] At the same time, there were small-scale outdoor exhibitions that were mounted and seen by a limited number of artists, and which can probably be thought of as a reaction to the failure of the Contemporary Art Outdoor Festival. Half a year after the festival, Takayama Noboru, Enokura Kōji and two other artists showed their works at Space Totsuka in Yokohama, which was a large garden next to Takayama’s apartment, in 1970 [Image 1]. Many of their works were site-specific, with a focus on the use of natural materials and their process of natural transformation. Only a small number of people visited the site but the exhibition later received much acclaim. It was followed by Points Exhibition in 1973, joined by Shima Kuniichi and thirteen other artists, who produced their works and performances in their own homes and neighborhoods, some of them making the best of the sites’ spatial features.[15] These exhibitions epitomize the artists’ retreat from a broad public audience as well as political issues in the society of the 1970s.

![Enokura Kōji, Shisshitsu [Quality of Wetness], 1970. Installation view at the exhibition “Space Totsuka ’70,” Yokohama, Kanagawa, December 5-20, 1970. From Enokura Kōji: A Retrospective (Tokyo: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2005), 77.](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/01-Enokura.jpg)

Practices such as these provided the background for the boom in outdoor sculpture exhibitions in the 1980s, most of which were run by artists and held in natural settings in the countryside. Most notable are the Hamamatsu Outdoor Art Exhibition on the Nakatajima Sand Dunes in Hamamatsu between 1980 and 1987, the Ōya Underground Art Exhibition in an underground quarry in Ōya in Tochigi between 1980 and 1989, Ushimado International Art Festival in Ushimado, Okayama between 1984 and 1992, and projects by the artists’ group Amatsuchi Kōsaku, meaning “cultivation between heaven and earth,” conducted in Hamamatsu between 1988 and 1999. Like the small-scale exhibitions of the 1970s, most of these outdoor art exhibitions in the 1980s were interested in creating art works in vast landscapes rather than attracting an audience. Since some of the exhibitions were held deep in the wilderness, it was sometimes difficult to gain access to the site of the art works. They sharply contrast with the art projects in the 1990s, which came to pay attention to their relationship to the audience, and thus comprise a prehistory of art projects in terms of non-museum-based exhibitions. In this prehistory we can see that social engagement was not emphasized. To the contrary, artists were moving into the countryside to get away from social entanglements, as well as to explore the potential of vast spaces.

Public Art from the United States

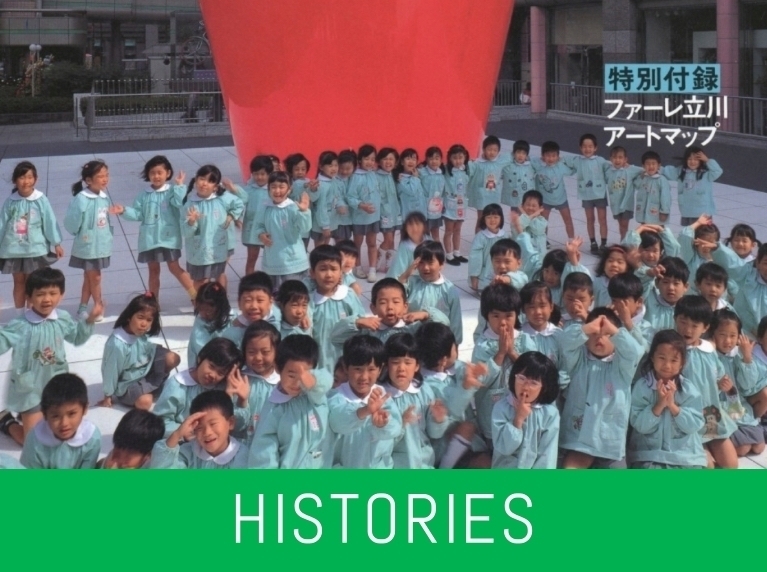

The shifting discourse on public art in Japan in the mid-1990s appears to be another important source for art projects. This new discourse usually used “paburikku āto,” the transliterated phrase from English, instead of translating it into “kōkyō geijutsu.” By the late 1980s, the discourse on public art that emerged in the U.S. from the 1970s was known among art professionals, but it was not until the mid-1990s that actual public art works appeared in Japan at a full scale.[16] In 1994, KITAGAWA Fram directed the Faret Tachikawa Art Project, installing 109 art works outside 11 buildings, including offices, a hotel, a department store, a movie theater, a public library and others [Image 2]. In the next year, NANJŌ Fumio, a former Japan Foundation official and current director of Mori Art Museum, directed the Shinjuku i-Land Public Art Project, which installed 14 artworks in and around five buildings including offices, restaurants, shops, residences, and a school [Image 3]. After these large-scale projects, the term “paburikku āto” spread around the country, leading to a wave of new public art works being installed in streets, parks, and inside buildings.

![The cover of Paburikku āto no sekai [The World of Public Art] (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1995).](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/02-world-of-public-art.jpg)

![The cover of Paburikku āto no genzaikei: Shinjuku airand āto keikaku [The Present State of Public Art: Shinjuku i-Land Art Project] (Tokyo: Kajima shuppankai, 1995).](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/03-Present-State-of-Public-Art.jpg)

The cover of Paburikku āto no genzaikei: Shinjuku airand āto keikaku [The Present State of Public Art: Shinjuku i-Land Art Project] (Tokyo: Kajima shuppankai, 1995).

There were of course a lot of artworks installed in public places before the popularity of US-based public art, but they were not regarded as “paburikku āto” even after that term had become popular. For instance, the 1970s saw a massive investment by local governments in outdoor sculptural pieces, as mentioned above. But such public sculptures, while increasing the cultural value of a place and contributing to the maintenance of urban environments, tended to be ambiguous in their subject matter and innocuous in their form, and many had almost no relationship to the specific character of the installation site. Part of the reason for this may lie in the selection process for the pieces: in many cases, artists were directly commissioned, invited to join closed competitions, or asked to sell preexisting works. The number of open calls was very small and there was little attempt in most cases to make the selection process public.[20] That is why public sculpture installation projects produced many outdoor sculptures that were not based on public values but were sustained primarily by the personal sensibility of the artists.

The public art that appeared in Japan in the mid-1990s presented itself as correcting these mistakes, declaring that it would be conscious of the relationship between art works and the places they are installed. When he selected art works for Shinjuku i-Land, Nanjō wrote that he put an emphasis on whether the artwork establishes a dialogue with its context. According to Nanjō, there were two kinds of context: one the “cultural and historical context” and the other the “forms and colors of nearby spaces and architectural features.”[21] However, he then quickly dismissed the relevance of the first kind of context for the Shinjuku i-Land, writing that it “does not have a cultural history that deserves special mention, so in that sense we had no choice but to think in terms of spatial context.”[22] The ten selected artworks included works by Daniel Buren, Robert Indiana, Sol LeWitt, and Roy Lichtenstein, many of whom make public artworks not in relation to the cultural and historical context of a site but in their own signature style.

For his part, Kitagawa wrote that when he planned Faret Tachikawa, he wanted to “install artworks as objects with a variety of functions such as traffic signs, benches, and lights, not just to put them out in the open air.” He wanted to create “a forest” in the city that would revive and nurture people under three concepts: “the town that reflects the world,” “make function into fiction (art)!,” and “the town of wonder and discovery.”[23] His concepts suggest that he was interested in connecting artworks with their location, indicating criticism towards conventional public sculpture installation projects. He also seems to aim to counteract the dehumanizing aspects of the city through his own humanistic thought as well as his broad interest in the trends overseas, including public art in the United States and Skulptur Projekte Münster in Germany. But taking into account that Faret Tachikawa was built as part of the redevelopment of a former US military base, Tachikawa Airfield, which had been the focal point of a fierce opposition movement from 1955 to the early 1960s, we can see Kitagawa also emphasizes spatial contexts rather than cultural and historical ones when he relates art to the city.

The public art in mid-1990s Japan did not take the form of single monumental pieces like La Grande Vitesse by Alexander Calder in Grand Rapids, but involved the total design of an area and many sited artworks, as in Kitagawa’s and Nanjō’s projects. That structure resembles the basic framework of many art projects since. Public art often entails a large-scale development with large budgets provided by local governments and corporations, which has led to the rise of arts management as a necessary part of non-museum-based exhibitions. In fact, the scale of art projects led by Kitagawa has become bigger and bigger over the last twenty years. Because the popularity of public art declined in Japan with the collapse of the bubble economy in the early 1990s, before ideas like “new genre public art” had a chance to be discussed seriously and widely, the idea of public art as being something to show the spatial possibility of installing art works in the city remained intact. Nevertheless, public art created a ground for starting to think about the public meaning of art and the role of arts management, paving the way for the emergence of the art project in Japan.

Jan Hoet’s Curation

The activities of Jan Hoet are a third important source for the art project in Japan. The Belgian curator and founding director of the City Museum of Contemporary Art in Ghent, Hoet organized the Chambres d’Amis exhibition in 1986, in which 51 artists installed artworks at 58 private residences in the city for the public view. The show is best known for its relational character, since the participating artists got involved with the owners of the sites when they installed their works. The viewers also needed to interact with the owners when they visited a particular work. Hoet’s show had a great impact on the art world in Japan. There were precedents in Japan too, such as the Points Exhibitions (1973–76) and KAWAMATA Tadashi’s Apartments Projects (1982–83), where he showed his works in private apartments and houses, but they were not well known enough to have had a big impact. It seems that there were not many art professionals who actually visited Ghent to see Hoet’s show, but through his frequent visits to Japan hosted by the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art (the leading institution for introducing the world’s contemporary art to Japan at the time) Hoet became familiar in Japan as a world-famous curator. When he first came to Japan in 1986, he visited Tokyo, Nagoya, and Kanazawa and came again in 1991 to curate the “Shikaku no Uragawa [The Reverse of Vision]” show at the Watari Museum,[24] the One-Day University of Contemporary Art—a workshop where he critiqued works by a hundred artists, and the “Jan Hoet in Tsurugi: Contemporary Art and the Town Space” exhibition where works by 34 artists he had selected at the workshop were displayed at warehouses and houses in the small town of Tsurugi, Ishikawa, followed in 1994 by “Jan Hoet in Tsurugi, Part 2,” for which Royden Rabinowitch, Bill Woodrow and Franz West visited the town to make and show their art works [Image 4].[25] Aside from the difference in scale and influence, this non-museum-based exhibition was comparable to Chambres d’Amis in its intent and format. Moreover, Hoet curated the “Mizu no Hamon [Ripple across the Water] ’95” show in the Aoyama area in Tokyo, where works by 48 artists were shown at more than 30 venues including in the streets, office buildings, a kindergarten, a park, a graveyard, and a temple. Prior to the exhibition, the participating artists visited eight places around the country, Sapporo, Sendai, Noto, Tsurugi, Okuetsu, Nagasaki, Minamata, and Tokyo to “make art works, converse with local people, and use the indigenous features of the place, such as traditions, climate, histories, problems, and prospects.” These art works were brought to Aoyama and shown there. Broadcast on TV and reported in newspapers and popular weekly magazines, this exhibition made Hoet something of a household name. Through these opportunities, non-museum exhibitions in urban spaces and site-specific art production became widely known in Japan as a new trend in contemporary art in Europe.

To sum up, the major sources for art projects include outdoor exhibitions, public art (as it contrasts with previous practices of public sculpture), and Jan Hoet’s activities. Although there are other factors, these three sources are vital for the emergence of the art project in its typical form.[26] They tended to place emphasis on spatial possibilities outside the context of museums, contributed to the development of the arts management system, and focused on the use of buildings and houses in the places they were sited. This lineage shows that Japan’s art projects do not derive directly from the influence of relational art nor from socially engaged art. The concepts of relational aesthetics and socially engaged art came to be known in Japan respectively in the early 2000s and in the mid-2010s, when art projects were already thriving.[27] Therefore, it is little wonder that Japan’s art projects have a different structure from relational art and socially engaged art in Europe and the United States.

The Emergence of Art Projects

It was in the 1990s that art projects manifested themselves as a discreet form. In contrast to the eighties, when exhibitions were organized mostly by artists, curators in the 1990s began to get involved with outdoor exhibitions and introduced artist-in-residence programs, workshops, and educational initiatives to them. Art Camp Hakushū, one of the first art projects, started in 1988 as The Hakushū Summer Festival [Image 5], and was held annually until 1999 in a mountain village called Hakushū in rural Yamanashi. It staged dance, music, and performances in addition to exhibitions, and was organized by butoh dancer and choreographer Tanaka Min and art producer Kobata Kazue. The location of the festival was a commune of sorts where Tanaka and other dancers lived and danced while working as farmers. The festival strongly reflected their danceʼs orientation towards traditional performing arts and indigeneity. At the same time, it adopted some features of the precursors discussed above: the openness of outdoor exhibitions, public art’s management system, and Hoet’s idea of walking around from location to location. It came to constitute the structure of later art projects where audiences walk around to see art works while enjoying the scenery; where many artists, volunteers, and visitors come from inside and outside Japan; and where funds are raised through subsidies.

Another example of early art projects is Museum City Fukuoka, based in the regional city of Fukuoka. Initiated in 1990 as Museum City Tenjin by local artists and volunteers from local government and corporations, Museum City Fukuoka took a biennale format and was held until 2004 [Image 6]. This exhibition, while exhibiting works around the city by artists from inside and outside of Japan not only at outdoor spaces but also inside commercial buildings, also organized artist-in-residences, workshops, and art schools, and became a model for an urban type art project that creates various meeting places within the city for artists and residents.

![Morimura Yasumasa, Hana to hōchō [Flower and Knife], 1990. Installation view at the court of IMS (Inter Media Station) at the exhibition “Circulation of Sensibility: Visual City, Functioning Art,” Museum City Tenjin, Fukuoka, September 17–November 4, 1990. Myūjiamu shitei purojekuto 1990-200X: Fukuoka no “machi” ni deta āto no 10 nen [Museum City Project 1990-200X: 10 Years of Art that Appeared in the “City” of Fukuoka] (Fukuoka: Myūjiamu shitei purojekuto shuppanbu, 2003), 58.](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/06-Morimura.jpg)

![PH Studio, Fune o tsukuru hanashi [A Story of Building a Ship], 1994 to the present. Haizuka Earthworks Project, Miyoshi, Hiroshima, 2002. The courtesy of PH Studio.](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/07-PH-Studio.jpg)

Art Projects in the 2000s

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is one of the most important art projects in the 2000s. It became a prototype for many projects that started after it. It is a large-scale exhibition that started under the direction of Kitagawa Fram in 2000 in Niigata, funded in its early years specifically because it was framed as a regional revitalization project promoted by Niigata Prefecture and the local governments in the Echigo-Tsumari area. The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is the first art project to cope with the issue of regional revitalization straightforwardly and has been one of the most successful in realizing its goals. Festival documents report that the first exhibition attracted 162,800 visitors and brought 114,600,000 USD (12,758,000,000 JPY) to Niigata’s economy and those numbers have grown.[28] Revitalization has become the primary field where art projects connect with local government initiatives.

The Toride Art Project is another representative example of a large and long-running project that grew in the new millennium. Launched in 1999 by an executive committee composed of Tokyo University of the Arts, Toride City, and its residents, the project is an ensemble of art works and projects by individual artists, open studio programs, symposia, workshops, and artists’ talks. Toride is about an hour from Tokyo, on the fringe of the outer suburbs, and hosts one of the campuses of Tokyo University of the Arts. The project aims at supporting young artists’ creative activities while providing residents in Toride with opportunities to connect with art more closely so that Toride City will develop as a cultural city [Image 8]. During the first four years, it was part of the curriculum of the Inter Media Art Department at the university. Through 2002, Kawamata Tadashi was a central figure in the project, but after he resigned from the university in 2005, young artists and residents came to play a central role in the exhibitions and related activities. Until 2009, the Toride Art Project was held as an open-call exhibition followed by an open studio program in alternating years. From 2010, it shifted to focus on two topics in an ongoing fashion: “Apartments with Art,” for which artists renovate apartments in a creative way and “Farming and Art,” in which artists incorporate farming into their lifestyle or help people to do so.

![The former Togashira Sewage Plant (left), Yanobe Kenji, Flora (center), Antenna, Hi izuru Fuji no kami: Rittai Raigōzu [Divinity of Mt.Fuji’s Sunrise: Three-dimensional Raigōzu], and Ozaki Yasuhiro, Kodai tenmondai [Ancient Observatory] and Blowin’ in the Wind (right), Toride Art Project 2006, Toride, Ibaraki, November 11–26, 2006. Photograph by Saitō Tsuyoshi. The courtesy of Toride Art Project.](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/08-Yanobe-and-Antenna.jpg)

![Hibino Katsuhiko, Yomikaeru Tokei [Clock Reinterpreted/Reborn], 2013. Installation view at the Signboard at the Shōfuda Takemura Department Store, Zero Date Bijutsu ten 2013 [Zero Date Art Exhibit 2013], Ōdate, Akita, October 4–27, 2013.](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/09-Hibino.jpg)

One of the reasons why art projects’ social consciousness is weak may be that they derived from outdoor exhibitions that developed chiefly with spatial interests in mind. Although artists’ strong interest in display was superseded in the 1990s by organizers’ emphasis on the audience’s experience, and in the 2000s by the cause of regional revitalization, it seems that artists’ spatial interest in non-museum exhibition remains unchanged. The interest in space and display could theoretically be pursued through exhibitions at museums and galleries, but art projects are assumed to be easier to organize. Outdoor exhibitions and art projects were attractive to artists and independent curators because they avoided the complicated process of organizing museum exhibitions. They enabled many artists and curators to show their works as they wished without having any affiliation with museums. This DIY nature of art projects comprises one of the main reasons why art projects are so popular in Japan among artists.

Legal Changes and Their Consequence

One final factor that we should pay attention to that affected the development of art projects is the way that new legislation on nonprofit activities and art promotion has made it easy to execute art projects but at the same time hinders their free activity, though not necessarily through direct regulation. As discussed above, art projects are concerned with art management systems. When corporate patronage of the arts developed in Japan in the late 1980s, the support went not only to museums but also to non-museum people and groups. Specialists in corporate support of the arts and business people in companies’ cultural support departments, who propagated the idea of art management in Japan, were interested in introducing management systems to art projects that would make interfacing with them easier, and encouraged art project organizers to consider their work from the perspective of management, favoring support of projects that conducted continuous activities and were professionally managed, not one-off projects and festivals. The enactment of the Law to Promote Specified Nonprofit Activities in 1998 provided further encouragement for emerging art project directors to consider them ongoing organizations. The 1998 law was revolutionary for civil society groups in Japan generally, which up until its passage scarcely ever chose to incorporate into legal entities.[30] In addition to making it easy for such groups to incorporate, there was a lot of discourse at the time promoting such incorporation as a new way of doing things. Moreover, the Fundamental Law for the Promotion of Culture and Arts, which was enacted in 2001, laid out the responsibilities of national and local governments in promoting culture and the arts, resulting in an environment where local governments found art projects to be a form that was particularly easy to work with.

From the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, local and national government arts policy focused mainly on public building construction—museums, theaters, event centers, and such—to the neglect of actual content and programming for the institutions that were built. This was much criticized from the late 1990s onward, and in its place emphasis shifted in the opposite direction, towards programming, a demand which the organization of art projects could fill, thereby gaining greater access to grants and subsidies. These organizational forces therefore also encouraged the growth of art projects in certain directions: because they intersected with the policy of local governments they increasingly tended to avoid controversial works that could stir public disapproval. I believe that what should be discussed in evaluating art projects is not what management system they have but what they achieved by curating the shows with the artworks they selected. The increasing degree of dependence on grants and subsidies limits Japanese art projects’ connection with diverse social contexts, making them comparatively harmless and moderate.

Kawamata Tadashi’s Choice

For all that, one might say that at least art projects are accessible and beneficial to local residents. But Kawamata Tadashi’s experience might prompt us to reconsider even that. Kawamata has talked about his art practices as “projects” since the early 1980s and also was involved in founding the Toride Art Project. Kawamata has participated in a number of art projects, including the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, where he got involved a year before its start in 2000. Thinking that the Triennale appeared to be getting less stimulating and more monotonous, Kawamata, as part of a research group looking into art’s potential role in community care, conducted the following experiment in 2010, after the fourth exhibition:

Since almost all the local people I met said, “the art triennial has cheered us up,” I wanted to see whether they were actually cheered up so I went together with a psychiatrist to do house calls with people. We dropped in on villages and talked with people for an hour or so, asking what art meant to their village and things along those lines. One finding from that research was that there were quite a lot of people with manic depression. Another conclusion was that they really had no interest in art—even less than we expected. The Tsumari region is entombed in snow for half the year and has always had a high number of people suffering from depression. The “Echigo Tsumari” starting hardly mattered. Rather than finding out what art can do, we confirmed that the real problems of the region are deep. Of course, the people who live in the area don’t mind people coming and are happy to see visitors, but their own daily life is something completely different and we discovered that they were extremely cool towards the whole thing.[31]

What Kawamata’s findings call into question is not only a problem of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, but a structural problem applicable to other art projects in Japan, that is, the cyclical repetition that regularly held art projects have to follow, giving the residents momentary diversions rather than meaningful changes in their lives. Kawamata also argues that, in contrast to museum exhibitions regularly held in permanent spaces, art projects, as seen in the word “project,” should value process and resilience in their realization: monotony and repetition seem to be the opposite of that. In fact, Kawamata resigned from the chair of the executive committee of the Toride Art Project in 2003 and two years later also from a professorship at the Department of Inter Media Art at the Tokyo University of the Arts that led the project. Kawamata’s decision seems to be a warning to art projects and their current situation in Japan.

Conclusion

This paper critically examined the Japanese art project in historical perspective. First it examined the key critical discussions that have pointed to its weak social awareness. It then went back to the history of their development and showed that outdoor exhibitions, public art, and Jan Hoet’s activities were the historical sources for art project as they took shape in the 1990s. I also examined how key art projects in the 1990s and 2000s incorporated these sources into themselves. I argue that the art project is characterized by its emphasis on spatial arrangement and management systems, resulting—also with the effect of legislation—in the displacement of social context. I closed with Kawamata’s activities to highlight the problems that emerge for artists, viewers, and participants in the context of long-running art projects. Rather than compromising for the sake of continuous execution, I believe, art projects should return to their provisional and experimental beginnings and set out to transform themselves.

As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, the weakness of the social awareness in Japanese art projects is not derived from the character of the people nor a degradation of radical artistic practices in Europe and the United States. It is constructed historically and maintained by current legislative conditions and forms of financial and institutional support. Art projects have been regarded as more free and flexible than museum exhibitions but their freedom and flexibility are in fact limited and controlled by their reliance on local government and corporate grants, which constantly have to be re-applied for. In order to make art projects more creative and diverse, it is vital for curators and scholars in Japan to know much more about socially engaged art in other countries with special focus on the differences in history and theory. It is also important for their counterparts outside Japan to understand these differences. I believe Japanese art projects deserve more recognition in other countries and it is my hope that this article and others in this issue of the journal will improve the critical discussions on Japanese art projects not only to change the situation in Japan but also to enrich and diversify socially engaged art around the globe.

KAJIYA Kenji is an art historian and associate professor of representation studies at the University of Tokyo. Kajiya also serves as a director of the Oral Art History Archives of Japanese Art. He is a co-editor of From the Postwar to the Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945–1989: Primary Documents (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012) and 12-volume Selected Art Writings of Nakahara Yūsuke (Tokyo and Yokohama: Gendai Kikakushitsu and BankART Publishing, 2011–2017). His first book, Formless Modernism: Color Field Painting and 20th-Century American Culture, will be published by the University of Tokyo Press in 2018.

[1] This essay is a substantially revised version of an article published in in Japanese: “Chiiki ni kōken suru Nihon no āto purojekuto: Rekishi teki haikei to gurōbaru na bunmyaku [Japanese Art Projects Unfold Locally: Their Historical Background in a Global Context]”, in Fujita Naoya, ed., Chiiki āto: Bigaku, seido, Nihon [Local Art: Aesthetics, Institution, Japan] (Hachiōji: Horinouchi shuppan, 2016), 95–133.

[2] The two books are: Āto purojekuto: Geijutsu to kyōsō suru shakai [Art Projects: A Society that Co-Creates with Art], edited by KIKUCHI Takuji and NAGATSU Yūichirō, under the supervision of Kumakura Sumiko (Tokyo: Suiyōsha, 2014) and Fujita, Chiiki āto. See note 1 for Fujita’s book.

[3] “Sōsharī engējido āto” came to be known through the Tokyo version of the exhibition “Living as Form” in 2014, and the translation of Pablo Helguera’s Education for Socially Engaged Art in 2015 that uses the transliterated phrase in its title: Sōsharī engējido āto nyūmon (Introduction to Socially Engaged Art), both of which were led by the non-profit organization Art & Society Research Center. The original exhibition was first shown in New York in 2011 by the nonprofit arts organization Creative Time. The Tokyo version is entitled Ribingu azu fōmu (nomadikku bājon): Sōsharī engējido āto toiu chōryū [Living as Form (The Nomadic Version): 20 Years of Socially Engaged Art],” which was organized by the non-profit organization Art & Society Research Center and held at 3331 Arts Chiyoda, Tokyo between November 15 and 28, 2014. The Center also organized Sōsharī engējido āto ten: Shakai o ugokasu āto no shin chōryū [Socially Engaged Art: A New Wave of Art for Social Change] at the same venue between February 18 and March 5, 2017. Helguera’s book is published as Paburo Erugera [Pablo Helguera], Sōsharī engējido āto nyūmon [Education for Socially Engaged Art], trans. Art & Society Research Center SEA Research Lab (Tokyo: Firumu āto sha, 2015). For Art & Society Research Center’s activities, see the website: http://www.art-society.com. Some of their members also formed a group to focus on socially engaged art, joined by other art professionals: SEA Research Lab, http://searesearchlab.org.

[4] Fujita, Chiiki āto. It includes the English title “Community-Engaged Art Project.” Local Art is a literal translation of the Japanese title.

[5] Dokyumento 2000 purojekuto jikkōiinkai, Shakai to āto no enmusubi 1996–2000: Tsunagite tachi no jissen [Marrying Society and Art 1996–2000: The Practice of Match Makers] (Osaka: Dokyumento 2000 purojekuto jikkōiinkai, 2001).

[6] Murata Makoto, “‘Datsu bijutsukan’ ka suru āto purojekuto [Art Project Goes ‘Beyond the Museum,’” in Shakai to āto no enmusubi 1996–2000, 8–20.

[7] Kumakura Sumiko and Art Project Research Group, An Overview of Art Projects in Japan: A Society that Co-Creates with Art (Tokyo: Arts Council Tokyo, 2015), 4.

[8] An Overview of Art Projects in Japan, 9.

[9] Fujita Naoya, “Zenei no zombi tachi: Chiiki āto no shomondai [Zombies of the Avant-Garde: the Problems of Local Art], in Chiiki āto, 11–43.

[10] I have written three articles on this topic. In addition to the article mentioned in note 1, there are: “Art Project and Japan: Examining the Architecture of Art,” trans. NAKAI Yū, in Hiroshima Art Project 2008 (Hiroshima: Hiroshima Art Project, 2009), 152–161; “Nihon no āto purojekuto: Sono rekishi to kinnen no tenkai [Art Projects in Japan: Their History and Recent Developments],” in Hiroshima Art Project 2009 (Hiroshima: Hiroshima Art Project, 2010), 261–271.

[11] KuroDalaiJee (Kuroda Raiji), Nikutai no anākizumu: 1960 nendai Nihon bijutsu ni okeru pafōmansu no chika suimyaku [Anarchy of the Body: Undercurrents of Performance Art in 1960s Japan] (Tokyo: grambooks, 2010).

[12] KuroDalaiJee, Nikutai no anākizumu, 523–528.

[13] On this controversial festival, see my article, “Nihon no āto purojekuto,” 262–263.

[14] TAKEDA Naoki, Nihon no chōkoku setchi jigyō: Monyumento to paburikku āto [Sculpture Installation Projects in Japan: Monument and Public Art] (Tokyo: Kōjin no tomo sha, 1997).

[15] NAKAI Yasuyuki, Mono-ha: Saikō [Reconsidering Mono-Ha] (Osaka: National Museum of Art, 2005), 122–123. Points Exhibition was held in 1975 and 1976 too.

[16] SUGAWARA Norio, “Paburikku āto [Public Art],” Yomiuri Shimbun, 9 January 1988, evening edition, 9; NITTA Hideki, “Gendai Amerika no paburikku āto [Public Art in Contemporary America],” Miyagi ken bijutsukan kenkyū kiyō [Bulletin of the Miyagi Museum of Art], no. 3 (March 1988): 1–7; The August 1993 issue of Bijutsu techō features “Dare no tame no bijutsu nanoka: Paburikku āto no kanōsei [Art for Whom?: The Possibility of Public Art],” Bijutsu techō, no. 673 (August 1993): 15–94.

[17] Nitta, “Gendai Amerika no paburikku āto.”See note 16.

[18] Sugawara, “Paburikku āto [Public Art],”; Anonymous, “Sekai no paburikku āto [Public Art in the World],” Paburikku āto no sekai [The World of Public Art] (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1995), 108; KASHIWAGI Hiroshi, “Paburikku āto wa nani o kizukaseru ka [What Public Art Makes Us Notice],” Bijutsu techō, no. 673 (August 1993): 64–71.

[19] Anonymous, “Mondēru bei taishi fujin geijutsu shinkō de fukameru kōryū. Boranteia de kōen katsudō [Mrs. Mondale, the Wife of US Ambassador, Promotes an Exchange through the Advancement of Art. She Delivers a Lecture as a Volunteer],” Yomiuri shimbun, 28 January 1994, evening edition, 1. Mrs. Mondale contributed an essay on public art in the US to Paburikku āto no sekai [The World of Public Art], which featured Kitagawa’s Faret Tachikawa. Jōn Mondēru [Joan Mondale], “Amerika no paburikku āto [American Public Art],” 60–61.

[20] Takeda Naoki, Paburikku āto nyūmon: Jichitai no chōkoku setchi o kangaeru [Introduction to Public Art: Considering Sculpture Installation by Local Governments] (Tokyo: Kōjin no tomo sha, 1993), 73.

[21] Nanjō Fumio, “Āto ni okeru kōkyōsei no gainen to sono purakuteisu [The Idea of Publicness in Art and its Practice],” Paburikku āto no genzaikei: Shinjuku airand āto keikaku [The Present State of Public Art: Shinjuku i-Land Art Project] (Tokyo: Kajima shuppankai, 1995), 35–36.

[22] In fact, Shinjuku’s subcenter of Tokyo, the area that Shinjuku i-Land faces, used to be the Yodobashi Water Purification Plant. That means the site of Shinjuku i-Land does have some cultural and historical contexts.

[23] “Outline of the Art Project,” in Fāre Tachikawa āto purojekuto: Toshi, paburikku āto no shinseiki [Faret Tachikawa Art Project: A “New Century” for City and Public Art],” under the supervision of KIMURA Mitsuhiro and Kitagawa Fram (Tokyo: Gendai Kikakushitsu, 1995), 244–245.

[24] The official English title is “Irony by Vision.” “Reverse of Vision” is a literal translation of the Japanese title.

[25] The town of Tsurugi was merged with a city, a town, and five villages creating the new city of Hakusan in 2005. The selected artists included 29 year-old MURAKAMI Takashi, who was not yet known worldwide. On Hoet’s activities in Tsurugi, see WASHIDA Meruro, “Tsurugi gendai bijutsusai ni okeru chiiki to dentō [Locality and Tradition in Tsurugi Contemporary Art Festival],” Я [Āru]: Kanazawa nijūisseiki bijutsukan kenkyū kiyō [Bulletin of 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa], no. 6 (2016): 80–83.

[26] Murata writes that news of the 2nd Skulptur Projekte Münster directed by Klaus Bussman and Kaspar König in 1987 spread quickly in Japan together with Jan Hoet’s Chambre d’Amis. Murata Makoto, “Bijutsu no kiso mondai, no. 18 [Basic Questions of Art, no. 18].” http://www.dnp.co.jp/artscape/series/0112/murata.html (Accessed on March 26, 2017). Other factors that deserve mention include the non-profit art space called “Jiyū kōjō [Free Factory]” run in Okayama between 1993 and 1995 and the tradition of Japanese plaza and public space called “hiroba.” See INOUE Akihiko, ed., Jiyū kōjō kirokushū 1993.12.5–1995.3.31 [Documents of Free Factory] (Okayama: Jiyū kōjō, 1997) and ITŌ Teiji et al., “Nihon no hiroba [Japanese plaza and public space],” Kenchiku bunka, no. 298 (August 1971): 75–170.

[27] Art critic MATSUI Midori refers to relational art in her book published in 2002. Matsui, Āto: Geijutsu ga owatta ato no āto [Art: Art in a New World] (Tokyo: Asashi shuppansha, 2002), 160–161.

[28] Echigo Tsumari Āto Toriennāre 2003: Dai 2 kai daichi no geijutsu sai sōkatsu hōkokusho [Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale 2003: The Final Report on the 2nd Art Festival of the Ground] (Tōkamachi: Daichi no geijutsu sai/Hana no michi jikkō iinkai, 2003), 4. http://www.city.tokamachi.lg.jp/ikkrwebBrowse/material/files/group/4/000013095.pdf (Accessed on March 26, 2017).

[29] See Shakai kadai no kaiketsu ni kōken suru bunka geijutsu katsudō no jirei ni kansuru chōsa kenkyū hōkokusho [Report on the Research on the Cases of Culture and Art Activities that Contribute to the Solution of Social Issues] (Tokyo: Nomura Research Institute, 2005). http://www.bunka.go.jp/tokei_hakusho_shuppan/tokeichosa/bunka_gyosei/pdf/h26katsudo_jirei.pdf (Accessed on April 10, 2017).

[30] Law to Promote Specified Nonprofit Activities, chapter 1, article 1. https://www.gdrc.org/ngo/jp-npo_law.pdf (Accessed on March 26, 2017). Prior to this law, the primary way for civil society groups to incorporate was as an “incorporated association (shadan hōjin),” which had to be licensed by the government ministry that related to the group’s activity. Ministry officials could refuse to certify a group, leading to a strong government role in guiding such groups’ activities.

[31] Kawamata Tadashi, “Kakuitsu teki ni natta ‘saito supeshifikku’ o kowasu [Destroying the ‘Site-Specific’ that turned Monotonous],” in Āto purojekuto: Geijutsu to kyōsō suru shakai, 298.