Socially Engaged Art in Japan: Mapping the Pioneers

Adrian Favell

Introduction: What’s Missing in the Field?

The journal FIELD and, more generally, the theoretical frameworks developed by Grant Kester, ought to be a congenial place for discussing contemporary Japanese socially engaged art (SEA).[1] In rejecting the imperious quality of much radical critique as it is enshrined in art theoretical orthodoxy and its understanding of the political, and in recognizing the more pragmatic choices that community-based artists and art organizers make in order to advance collaborative artwork in everyday contexts, Kester has opened a broad perspective that is particularly well-suited for recognizing recent art and art organization in Japan. These are movements that have been largely missed in global curatorial debates. In his work, Kester identifies five distinctive features of collaborative artwork: locality and duration, the downplaying of artistic authorship, conciliatory strategies and relationships with specific communities, the process of collaboration as an end in itself, and novel organizational forms.[2] When taken together and practiced seriously—that is, as part of genuinely grounded fieldwork and social participation—such artwork can radically transform the nature of the political and the ways art participates in it.

As I will argue, much of what is being done in large-scale socially engaged public art projects in Japan, such as KITAGAWA Fram’s Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale or NAKAMURA Masato’s 3331 Arts Chiyoda, fit these pragmatically framed theories of engagement and social change. Not everyone sees them this way: Kitagawa himself, who is of an older generation, does not see himself as an artist or his organizational work as art. Nakamura, on the other hand, does. The significance of these large-scale art projects is remote from the concerns and assumptions that dominate discussions of theory in North American and European art education, curation, and art criticism. But viewed sociologically, as experiments in organizational form on a sometimes huge social scale, I believe some of these projects can be seen as constituting an extraordinary new form of artwork. Moreover, these projects have a rich lineage going back decades, as demonstrated in accompanying essays in this special edition of FIELD by Kenji KAJIYA and Reiko TOMII. It is more than a little perplexing, then, that it is almost impossible to trace any awareness of Japanese SEA in the international literature on relational, participatory, site specific, or socially engaged art.[3] The possible reasons for this elision are worth investigating.

Much of the development of socially engaged practices in Japan has occurred under the heading “art project” (āto purojekuto) rather than “socially engaged art” or “activist art”, a difference which may have contributed to a disconnect with the terms of global discussion. Kenji Kajiya has written about the development of both the form of the art project and the term.[4] As also defined in work led by KUMAKURA Sumiko, art projects are art-related initiatives, outside of the usual art and museum spaces, which engage with a wide range of ordinary citizens, often through particular modes of social organization. As Kajiya details, two early examples of what today would be called art projects were Art Camp Hakushu (1988-1999), organized by butoh dancer TANAKA Min with curator KOBATA Kazue in rural Yamanashi, and the Museum City Project (1990-2004) in the city of Fukuoka, led by art organizer YAMANO Shingo and the then-young curator KURODA Raiji. These were more than outdoor contemporary exhibitions: they focused on the process and quality of participation as much as the product, involved large numbers of volunteers, and were innovative in getting support from regional governments and corporations. The initial success and eventual dominance of the term “art project” in Japan can also be traced to the formulations of the prominent installation artist KAWAMATA Tadashi.[5] He emphasized two aspects of the meaning of art project: first, the idea of a work-in-progress or “de-work,” in which the art work is a “kind of collective representation . . . [of the] process of production”; and, second, the idea of “site-specific art,” which foregrounds acts of expression that are “only possible by intervening into the social context of community, locality or minority.”[6]

“Art project” is thus not only a different term, but a slightly different idea and entity from socially engaged art or collaborative art. As Justin Jesty suggests in his accompanying introduction to this special edition, Japan’s art projects are always public art, meaning that during their process of production they are politically or socially obliged to answer to both their audiences/participants as well as power-holders, that is, the authorities who finance or sanction the work. This fact has created another barrier to the international critical acknowledgement of art projects in Japan, parallel to the broader critique SEA often faces in international art theory. Local Japanese art projects rarely frame themselves with the acutely theorized political self-consciousness standard to most contemporary art worldwide, and for that reason can easily come across as unguarded, politically naive “community art” of the kind that Claire Bishop criticizes in her analysis of British SEA pioneers in the 1970s.[7] A recent lively debate in Japan about the potential co-optation and naiveté of “regional art” (chiiki āto), and the declining quality of young artists who find too many opportunities in rural art festivals with enthusiastic government funding, included many references to Bishop and Hal Foster, among others.[8] The lack of development of a strong, self-consciously political discourse about art in Japan has made art projects particularly vulnerable to such criticisms.

That said, there are genuine issues raised by the criticism. There is truth to the concern that artists in Japan are being drafted into welfare service for “neo-liberal” governmental agencies keen to withdraw their support from the most vulnerable sectors of society. And there is a distinct whiff of political co-optation hovering around many of the art projects embraced as part of community rebuilding since the triple disasters of March 2011. The idealised presentation of some projects can mask the social conflicts and divisions that have been produced by the disasters themselves and by the government’s general neglect of marginal populations.[9] Community-involved art may also, in its search for social consensus, converge with governmental attempts to de-politicize culture. These concerns need to be foregrounded, but they also need to be weighed against the diversity of specific projects.

The art project emerged in Japan in the 1990s and came into full bloom in the 2000s, tracking quite closely the emergence of a “post-growth” society in Japan, with the economy stagnating and the population declining. This is not just a matter of context, but a point where contemporary SEA in Japan can be seen to make a unique contribution to wider international debates, as a forerunner of similar trends elsewhere. That is to say, this body of work, collectively speaking, has an organic relevance to diagnosing and addressing the condition of post-growth societies: a condition that is now clearly emergent as a backdrop of post-industrial change in many locations well beyond the Japanese archipelago, which arguably arrived at this condition first.[10]

This larger trajectory is worth tracing a moment. By the end of the 1980s, Japan’s overheating economy was touted as a potentially ascendant rival to the United States as a form of organized capitalism.[11] With the bursting of the infamous bubble economy around 1990 (and not long after the death of the Shōwa emperor, Hirohito), Japan entered a long, slow relative economic decline. With increasing pressure from globalizing markets, most of Japan’s formerly industrially rich regional cities as well as its agriculturally rich countryside went into decline and population shrinkage, dramatically ageing as people of working age fled to cities.[12] Only Tokyo continued growing through this period. In 1995, the same year as the Kobe earthquake and the Aum Shinrikyo terrorist attack in Tokyo’s subway, Japan’s birth rate also started to decline, to one of the lowest in the developed industrial world. By 2005, the population itself had started to shrink and grey, with an unprecedented proportion of very old people. Projections now expect the population of Japan to be 20 to 30% smaller by 2050 (declining from 130 to 100 million), with as many as 30-40% of that number living as dependent retirees, and an annual population shrinkage of about half a million people (equivalent to losing a city like Nagasaki every year).

These kinds of social and structural facts provide a certain backdrop for any art that intends to be socially engaged. As we will see, this situation has provided the conditions, contexts, and raw human materials for the kinds of large-scale initiatives pursued since 1990 by visionary artists and art organizers in remote or marginal regional and urban locations. Therefore, although certainly not apparent in mainstream politics or the kind of tourist branding of Tokyo that is sold internationally and touted as part of the Olympics build-up, an emergent, parallel “post-growth” culture can be seen developing in the shadows of the national business-as-usual growth philosophy, still grimly pursued by successive governments.[13] It is this culture which shows up in the rich panoply of social art projects that can be found in Japan, and which has been developing long before the disasters of 2011 propelled them to the forefront of the national imagination.

Notably, though, these developments were not at all registered until recently in global understandings of contemporary art from Japan. This was largely because of a longstanding tendency to focus on contemporary Japanese art that is specifically linked with Japanese pop culture and high tech industries, evident in the ongoing international fascination with tendencies such as neo-pop, Superflat, and “Cool Japan”.[14] This warped interest has persisted internationally—especially in the U.S.—as long as the consumption of contemporary art from Japan was embedded in the branding of the country in terms of its weird and wonderful youth sub-cultures, lifestyle products, and popular anime and manga exports.[15] After March 2011 this has now changed. Broadly speaking, even mainstream contemporary art in the country has now taken a sharp and salutary turn towards critical social engagement, something which has begun to also register internationally, in the light of numerous exhibitions.[16]

While these are welcome developments, we should also be aware there is a risk of interpreting them as things that have happened only after 3.11. Corresponding to the proliferation of exhibitions, there has been a surge in critical production, emphasizing resurgent political concerns and new social forms of artistic expression.[17] Ironically, perhaps, it is only in this post-3.11 context that art criticism in Japan has made a sustained effort to connect recent Japanese art to the canon of internationally-known SEA, for example, referencing key figures such as Jacques Rancière or Nicolas Bourriaud.[18] Without an awareness of a longer historical lineage that pre-existed the recent turn, the fact that Japanese critics have only recently started discussing in earnest ideas such as “relational art” may be wrongly read by international commentators to confirm a Euro/American-centric art historical paradigm of dissemination: of “Western” innovations, along with their basic terms and concepts, arriving on “Eastern” shores only after they have developed in New York, London, or Paris.[19]

Mapping a Lineage

Beginning around 1990, SEA in Japan expanded dramatically during the 2000s. I cannot discuss the entirety of this history in detail here, but a list of some of the most prominent projects and organizations, with some of the leading figures associated with them, is a useful start.

The most visible projects and organisations would include: Kitagawa Fram’s Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in a remote, mountainous, and snowy region of Niigata prefecture (2000-present); Koganecho Bazaar (2008-present), an annual festival directed by Yamano Shingo, in a crime infested, low income zone of Yokohama; BankArt, a hub of social art projects coordinated by IKEDA Osamu in portside Yokohama (2004-present); the Toride Art Project (1999-present), an association linking a satellite campus of Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai) with an ageing suburban community outside Tokyo; Ueno Town Art Museum (2007-09), a project headed by Geidai Professor HOSHINA Toyomi, in the low-income shitamachi area of Tokyo; the Naoshima and Setouchi projects, financed by millionaire FUKUTAKE Sōiichirō, which have brought contemporary art to a series of industrially despoiled islands in Japan’s inland sea (1992-present; and 2010-present, respectively); the Beppu Art Project, which aims to revitalize a rundown hot spring resort town in Kyushu (2005-present) and is a collaboration led by artist YAMAIDE Junya with environmentalist SERIZAWA Tadashi; and the Asahi Art Festival (2001–present), a social arts incubation initiative begun by KATŌ Taneo that has grown into a network of related social art projects nationwide, directed by Serizawa. The artist Yamaide excepted, most of these figures are older generation art organizers (born in the 1940s or 1950s), whose organizational innovations would not be normally be classified as forms of conscious collaborative art practice. This form of practice—of social organization as an art form—is easier to recognize in the ongoing “life work” projects of a somewhat younger generation of artists, born in the 1950s, including YANAGI Yukinori, HIBINO Katsuhiko, FUJI Hiroshi, the above-noted Kawamata Tadashi, and Nakamura Masato, born in 1963, whose influential arts organization, 3331 Arts Chiyoda, I will discuss below.

Many of these initiatives are connected to urban and regional revitalization efforts funded by local government and/or privately. A sub-set, most notably in Yokohama and Kanazawa, were consciously part of the global wave of “creative city” policy ideas which have focused on arts-led social intervention and, often, the gentrification, of post-industrial or de-populated urban sites worldwide.[20] A more recent example of government enthusiasm for these initiatives is the way that Echigo-Tsumari has been adopted as a model for regional policy (chihō sōsei) amidst debate about how the fruits of Tokyo staging of the Olympics might spread beyond the global megalopolis.[21] But the recent interest of Japanese government agencies in these projects, in most cases, belies the distinctiveness of Japanese art projects and the many years of struggle that the leaders of the projects undertook to establish the viability and sustainability of social and collaborative practices of contemporary art in environments and among populations where any aspect of contemporary art was alien.

Echigo-Tsumari is the most emblematic of these large-scale projects developed in the 2000s.[22] It is a huge scale contemporary art triennial that takes place in an area of around three hundred square miles of remote mountainous countryside, which has a total population of about 100,000 (mostly living in the small central city, Tōkamachi). It is a classic heartland of Japan, famed for its rice production and its terraced rice fields, but suffering vertiginous population decline and crumbling infrastructure. It is, like many areas of Japan, full of abandoned houses and derelict fields; but also empty schools, factories, and even hospitals, with roads sometimes tunneled through mountains leading nowhere. Its villages are overwhelmingly populated by very old residents, many of whom are former farming families now unable to tend their land. In the late 1990s, the art producer Kitagawa Fram was recruited to create an art festival, whose aims were to generate some spark of tourism-led revitalization as well as connecting recently unified local governments.[23] Kitagawa was both an experienced corporate/political operator and a political idealist, with strong anti-urbanist ideas that are a mix of Japanese traditionalism and an idiosyncratic variant of Maoism. He was also a well-respected, internationally-connected curator. Nevertheless, it was almost impossible to convince local politicians and (especially) local residents of the benefits of bringing contemporary art or, in particular, difficult contemporary artists, to their remote localities. Yet with persistence and persuasion, he convinced some municipalities to let artists work with them. The first Triennale in 2000 launched a series that was initially based on siting public art in remote locations, to be found by visitors as a kind of treasure hunt through villages, across fields, and up mountains. Over the years, this has extended to over two hundred sites, many of which involve repurposed abandoned houses, schools, and other empty buildings. Involving numerous international figures, countless Japanese artists, and thousands of volunteers, the Triennale has expanded to become one of the largest contemporary art events in the world, as well as a paradigmatic example of the social ambitions of Japanese art projects.

The Triennale is, in effect, the “expanded field” writ large. While many individual works or projects only remained in place for one iteration of the festival, the ones that have continued over a few triennials were, and are, long duration, unpredictable, and open-ended social experiments bringing artists and many young people—typically, art student volunteers—into contact with older residents in half-empty village locations, many nestled deep in the mountains. One archetypal long-running project is the 1980s pop artist Hibino Katsuhiko’s Asatte Shinbunsha (Day After Tomorrow Newspaper Company), an on-going residency in an empty village school, in which young students produce a daily newspaper based on the trivial (and not so trivial) everyday lives and events of the village’s few remaining residents. Hibino visits the village a number of times a year for events and to reconnect, independent of the Triennale schedule. This and many other of the long-running initiatives fit well into paradigms of conversational and collaborative art, while their long-running nature, unsure beginnings and ends, and lack of high-brow theorization put them well outside even the most expanded idea of the commercial or museum system.

Many visitors experience the Triennale as being about more than the collection of artworks alone: occasionally failing to find one of the locations on the map doesn’t necessarily matter if visitors end up chatting with residents or stopping to eat something instead. That is also part of the point.[24] The Triennale worked to bring urban populations into contact with remote localities, slowly winning over local residents to embrace the festival as a worthy cause for the whole region. Kitagawa, who never saw himself as an artist, was in effect using art as a massive tool of social intervention and transformation: not just bringing tourists to the area but transforming locals, visitors, and their relationship in the process. By any account, it is a remarkable vision of what art can be and do.

Though largely ignored in its early years, the paradigm shift heralded by Echigo-Tsumari was grasped early on by NAKAHARA Yusuke, one of Japan’s leading art critics since the 1950s, in his essays for the Triennale catalogs. In addition to noting how the Triennale opened up new possibilities for a largely unexplored idea of non-urban art, he also saw the potential for a “reconsideration of the formats for what we describe as art exhibitions,” as well as for “change not only among the residents of the region but also among the participating artists themselves.”[25] Written in the year 2000, these comments turned out to be prophetic. We might link these insights to something expressed well in curator Kuroda Raiji’s recent writings on globalism in which he suggests that part of Asian modernity is necessarily a struggle for emancipation from the domination of the (Westernized) hegemony of linear urban, economic development: such that the unfinished drive of modernity in Asian contexts can indeed be expressed in the local, the vernacular, the traditional, and the peripheral.[26] Although much of Kitagawa’s rhetoric about destructive urban culture and lost rural roots is nostalgic and backward looking, Kuroda’s point, following Nakahara’s, suggests other reasons why we may be looking at the (East Asian) near future when visiting art in remote villages and among desperately old and isolated populations. The community care and collective negotiations involved in these projects may be the next step forward for a “post-growth” society more generally. This paradigm change becomes even more significant as the emphasis of artworks at these rural art projects have shifted from made-in-situ objects to the re-utilization of abandoned buildings.

Reiko Tomii emphasizes a similar point in her discussion of Japanese “contemporaneity” in the wilderness, starting with 1960s radical artists: in Japan, the leading edge of the contemporary can be found in collective community works.[27] Kitagawa himself is a living link with 1960s radicalism. Arriving in Tokyo for university in 1965 he was swept up into student politics as an activist and radical, protesting American bases in the country. However, the struggle of the late ’60s led him to disillusionment with purist left-wing politics, which he saw play out in their most destructive form in the internal executions of members of the Rengō Sekigun (United Red Army).[28] Reacting against this in his own organizational politics, he emphasizes pluralism and open communication. Part of his reorientation enabled him to cultivate links with an enlightened segment of corporate Japan in order to push forward a progressive agenda amidst a void in social commitment by mainstream government, which, as in much of the developed world since the 1980s, has embraced austerity towards welfare provision and increasing social inequality. Kitagawa’s approach underlay the success of a landmark anti-apartheid art exhibition Apartheid Non! (1988-1990), which he organized to tour 194 locations in Japan in a huge articulated truck marked by a red balloon, as well as the ground-breaking public art project Faret Tachikawa (1994), which he managed and which brought international artists to do in situ work in a suburb of Tokyo.

Kitagawa’s organizational partnerships and their pluralism is something that characterizes the work of many socially engaged art directors and producers of a generation slightly younger than Kitagawa. One prominent example is Yamano Shingo, who was inspired by constructivism as a young artist and who abandoned Tokyo in the 1970s to become an arts organizer in the regional capital of Fukuoka. He led a public arts initiative called the Museum City Project, which began in 1990 and ran for many years, gathering cooperation and support from corporate sponsors in the absence of public government support. This way of supporting public art was experimental at the time, developing new modes of public collaboration and spatial intervention in the city, eliciting support from and feeding back into the lively local culture of alternative art spaces.[29]

Kitagawa also collaborated with and encouraged other significant art organizers in and around Tokyo, such as the architecturally trained Ikeda Osamu (Kitagawa’s younger colleague who leads BankArt in Yokohama), as well as Geidai professor Hoshina Toyomi. All were involved in the early career of Kawamata Tadashi, who was represented by Kitagawa’s Tokyo Hillside Gallery, and in earlier days was a close friend and colleague of Hoshina at Geidai.[30] With their organizational backup, Kawamata developed his early radical outdoor works in public spaces and indoors in vacant apartments. In particular, Yamano helped produce Kawamata’s landmark post-industrial project in Kyushu, the Tagawa Coal Mining Project (1996-2000). This rolling project involved ex-miners and students in re-imagining a former mine site as an “active memorial” to local labor history, responding to the economic decline of the locality and its unemployment.[31]

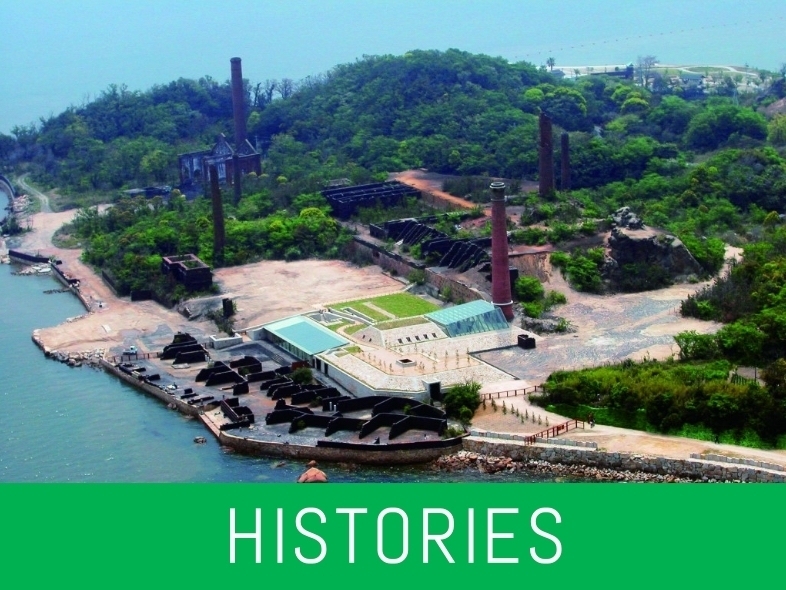

The other young artist represented by Kitagawa at his Hillside Gallery in the late 1980s was the politically minded “neo-pop” artist Yanagi Yukinori. Yanagi graduated from art school in the mid-1980s to almost immediate international acclaim for his technically accomplished installation works, which critiqued at once Japanese and American nationalism, integrating easy pop references (such as iconic Japanese toys and Disney) while also expressing a cosmopolitan rejection of nationalism. His most famous work remains his Ant Farm Project (1990), first imagined when he traced the “wandering position” of an ant around his Yale University studio. After filling boxes of colored sand representing different flags of the world and connecting them with tubes, he released large desert ants whose movements slowly mixed up the sand. One morning in 1995, when Yanagi was already tiring of his then-booming commercial career in New York, he landed his sailboat on a remote, formerly industrial island in the Seto Inland Sea.[32] This location, the abandoned copper mine on Inujima, became—via the benefaction of a local millionaire, Fukutake Sōiichirō and the collaboration of an innovative environmental architect, SAMBUICHI Hiroshi—the enormous Inujima Project, Seirensho.

The project centers on the mine itself, which has become an eerie, Pompeii-like monument to de-industrialization, housing a collection of memorabilia of the nationalist literary icon MISHIMA Yukio. The island’s population is now moving towards extinction, and the island itself is sustained almost entirely by the art and the visitors it brings. Others can also claim contributions to the site at Inujima, notably the renowned architect SEJIMA Kazuyo and the leading Japanese contemporary art curator HASEGAWA Yūko, who has acted as artistic director of the island’s art house projects since 2010.[33] These originally were used to house Yanagi’s work. Through his work on Inujima and other projects on large post-industrial sites, in the city of Hiroshima and on another depopulating island called Momoshima, Yanagi has developed a singular aesthetics of social art intervention imagined on a vast scale, built around his installations and re-workings of old buildings, embedded always in complex local negotiations with both local authorities and desperately old and vulnerable local residents.[34] Evoking an old situationist idea, he describes his work on the remote islands “not as the means but the very end itself . . . the frontline base of a very serious form of play.”[35]

From Art Project to Social Aesthetics

Yanagi and Kawamata’s massive projects in Seto and Kyushu in the 1990s discovered in some of Japan’s industrial ruins an immense new context and set of thematic issues for artists’ work. The 1995 Kobe earthquake undermined the assumption of modernity’s stability and irreversibility for many in Japan. Radical architect ISHIYAMA Osamu famously piled up the ruins of Kobe—literally—in the Venice pavilion for Fractures (1996), alongside the apocalyptic photography of MIYAMOTO Ryūji. Architect ISOZAKI Arata may have foreseen this future already as a disillusioned Metabolist in the early 1960s when he so eloquently wrote in the notes accompanying his artwork Incubation Process (1962) that all economic development contains within itself its own ruins.[36]

The disasters of 2011 have raised similar questions with greater intensity. They were echoed notably in architect ITŌ Tōyō’s reflections on the 3.11 disasters and the hubris of Japan’s architects and urban planners.[37] The cities destroyed by the tsunami were obviously not the touristic vision of hyper-modern “neo-Tokyo,” but rather the typical, shabby provincial towns, full of old people, that fill the archipelago’s declining regions. After 3/11, to paraphrase Yanagi’s allusion to Johan Huizinga (noted above), artists and their collaborators were playing in the ruins again. Three brilliant examples amongst the younger generation spring to mind: Chim↑Pom’s KI-AI 100 (2011), an absurdist video in which the six strong group joined some local youngsters amidst the devastation of their hometown, to shout out in a huddle a hundred daft “energy chants” that came into their heads;[38] TAKEUCHI Kōta’s (2011) allegedly incognito performance of a unidentified “Finger Pointing Worker” standing in front of live online cameras filming the ruined site of the Fukushima nuclear power station;[39] and KATŌ Tsubasa’s (2011) The Lighthouses—3.11 Project, in which he persuaded hundreds of local residents to join him in a public event to heave up large wooden handmade replicas of lighthouses swept away by the tsunami.[40] Making art out of the “ruins of Japan” might be everyone’s future in a “post-growth” society, with grass growing over the abandoned buildings and concrete expanses everywhere. Though already large-scale, when set against the onset of demographic decline, the abandonment of provincial locations, concentration of capital in the centre, growing political apathy, and massive environmental damage, these post-industrial projects take on an even greater grandeur.

As well as an abundance of ageing retirees, often living as the last generation in their town or village, there is a growing population of young people who are seen as a lost generation, facing “no future” as they are shut out of a society and economy in rapid contraction. The often immense level of volunteer participation in Japanese art projects has one of its roots here, as this “creative surplus” is able and motivated to work on community art projects. For young artists and creators, one can also speculate that the long-running weakness of Japanese art institutions when it comes to supporting contemporary art by Japanese artists contributes to the popularity of these alternative contexts. Artists started working off the map in a way much less possible in the U.S. and Europe, where art-institutional structures and discourses almost immediately recuperate radical gestures outside of art back inside recognizable art contexts.

To come back to Yanagi, however, his work, like that done on Inujima, still takes the form of an end product, or at least a singularly concentrated site of production/display: monumental locations and installations, together with conventional commercial and museum objects as its spin offs. Another mode of artwork makes the social work itself (i.e. the negotiations entered into, the agreements made, the new relations forged) the site of the aesthetics. Here, I would like to focus on Nakamura Masato (born 1963), currently the director of 3331 Arts Chiyoda, as a central figure in developing such social aesthetics, beginning in the 1990s.

As with other figures mentioned thus far, the scale and ambition of his work is immense. He directs a huge art center in a former middle school building near Akihabara—a hub for art events, continuing education for art students, exhibitions, and local social care projects, as well as off-site projects. These include local events such as TransArt Tokyo, an annual street and neighborhood based festival; and remote ones, such as the huge WaWa Project, which has been one the largest on-going frameworks for artist involvement with, and documentation of, the post-Fukushima disasters.[41] While the scale of his ambition may be similar to that of the older generation discussed so far, Nakamura is different in that he resolutely retains an identity and self-conception as an artist. Each of his projects involves complex and often experimental ventures into public logistics, lobbying, and coordination. At the time of his 2015 retrospective exhibition at 3331, Luminous Despair, Nakamura himself underlined that they could be read in their totality as a type of organizational art work.[42]

Nakamura acknowledges the important inspiration for his projects in the work of Hibino Katsuhiko (discussed above) and Fuji Hiroshi: figures who have established their own long-running autonomous art systems, involving volunteers, long term residencies, and complex forms of negotiation and transaction, as modes of social art work. Fuji Hiroshi is a quietly influential artist who has developed the idea that social art work is the work of building “operating systems” which allow users to create and interact. His most famous work is the Kaekko project, an NPO that operates nationwide, setting up events called “bazaars” for children to trade toys and build new ones from the ones already donated. The events are usually linked with educational initiatives like earthquake preparedness that integrate into the currency system of the bazaar.[43]

The scant international coverage that Nakamura’s 3331 show received treated it as a “comeback”: his “return” to practicing solo art, amidst all his “other” organizational activities.[44] The show contained various new installation pieces alongside his extensive photography from the crucial years 1989-1994, when he was, with MURAKAMI Takashi and a number of other household figures in Tokyo art, right at the center of the birth of a new contemporary art scene. Certainly it is possible to see the continuities in his work. The new installation pieces echoed TRAUMATRAUMA (1997), a key work of that period; particularly one room, in which he installed a series of wall-mounted metal panels in the most popular commercial colors, commissioned from a car manufacturer. In 1997, at the Tokyo gallery, SCAI the Bathhouse, Nakamura had installed neon lighting panels representing the colors of four convenience store (conbini) trademarks, some of the most instantly recognizable urban signs in Japan. On the one hand, the visual appearance and the courtship with commercialism in these works link them to neo-pop, but on the other, the true breakthrough with the conbini work was the complex negotiation and intense persuasion with four reluctant international corporations necessary to achieve the installation as a work of art.

In 1997, Nakamura finally succeeded in getting all the major convenience store companies at once to let him use their powerful brand icons. At Venice in 2001 he repeated the feat when he persuaded the biggest, most notorious corporation of them all—McDonalds—to let him install a huge, illuminated version of their brand sign “M” in the Japanese pavilion. The international art world response was apathetic. “Why that logo specifically?,” everybody asked. “‘M’ is my initial and yellow my signature color,” he would say: a dissimulating answer to be sure, but also an acid commentary on contemporary Japanese national identity. The discomfort he felt at Venice as a “token Asian” in the nation-based global art system is something he still emphasizes.[45] The experience marked the end of his career as a commercially oriented artist. Perhaps the brand—arguably the single strongest commercial icon of modern capitalism–was too powerful to become anything other than itself within his artistic process or the exhibition space. Yet again, what was key was the negotiation process that made the work possible; it was this process that Nakamura subsequently developed as a core feature of his practice. Accordingly, his work around the turn of the millennium was changing. In the Akihabara TV project (1999), he was already negotiating with the owners of consumer electronic stores in Akihabara to display experimental video works by 25 artists on the display TVs in their shops, inserting art work into the flow of everyday commerce.

Nakamura’s method evolved into an ever more subtle art of planning, persuasion, permission, and logistics: of working out how, in a society as potentially byzantine and publicly conservative as Japan, independent, interventionist yet public work might still be possible through collaboration with locals, fellow creatives, the authorities, politicians, bystanders, indeed anyone who can be persuaded to help. Nakamura speaks of “effecting change by burrowing inside institutions.” Thus his mode of working shares many similarities with Kitagawa. But crucially, he consciously frames it as artistic activity. There is also an interesting contrast with his old partner, Murakami. Murakami’s ultimate significance as an international artist (as Paul Schimmel notes in the retrospective ©MURAKAMI), no less than Nakamura, rests on his art as organizational practice: he founded a production company, created a factory, and recruited followers in the image of a traditional master’s atelier.[46] But this was a practice lodged in the lineage of Warhol, driven by commerce: an ironic infrastructure, but one which nonetheless mass produces work and provides commercial rewards that sustain the artist’s reputation in art theory and art history. The difference with Nakamura’s organization-as-art is that it is dedicated to non-profit ends. Nakamura’s non-commercial organization can be seen as an extended play on a Beuys-ian ethic of transformative social art, as arguably can Kitagawa’s. Nakamura’s life’s work as a social artist has been dedicated to social inclusion and social change, and he himself is largely submerged in the organizations and activities he has created and oversees. Nakamura has now set his sights on his home region, the northern tip of Akita prefecture, specifically, saving the crumbling industrial town of Ōdate. In this project, Zerodate, he is bringing his organizational approach to the conversion of an abandoned department store. Plans here involve the recruitment of teams of young volunteer leaders to create a sustainable form of intervention over time, as well as extensive programs of both visiting and local arts and crafts.

Coda: The Next Generation?

One major problem with the story I have been telling is that all of the characters in it are charismatic, ambitious male artists and art organizers, mostly in their ’50s and older. Look at the documentation of the many public panel discussions hosted by any of the remarkable art organizations discussed here, and the tale is likely to be the same: a line of distinguished looking men on stage talking with microphones in hand. Socially engaged public art projects in Japan, the kind with large organizations, major funding, and the ability to mobilize large numbers of volunteers, it seems, are led by middle-aged men, invariably visionaries with driven personalities. Some seem almost like characters from a Werner Herzog film, with devoted schools and followers of their own. It is very much the same with other leading artists: Murakami Takashi’s Kaikai Kiki empire or NARA Yoshitomo’s massive collaborative shows of the 2000s, built with thousands of volunteers.[47] In contrast, there appears to be a lack of younger or middle aged women artists in Japan with this kind of “art power”. On the other hand, there are many prominent female curators and gallery owners. It is a highly gendered story. The reason for this would be well worth debating.[48] We may hope that there are other histories and futures yet to be discovered.[49]

What of the younger generation? USHIRO Ryūta (born 1979), the leader of Chim↑Pom, or KUROSE Yohei (born 1983), the leader of Chaos*Lounge, who are both men in their ‘30s, and who both run alternative schools for younger artists, certainly have ambitions to be educators and gurus.[50] But perhaps there is an alternative mode of social art work emerging in the figure of TANAKA Kōki, a pivotal figure in the generation after Murakami and Nakamura (he was born in 1975), both for his international success and his central role in so many art world debates in Japan today. Tanaka is a conversationalist, not an empire builder. He has, rather, tenaciously worked to build collaborative fora with like-minded artists, such as FUJII Hikaru and KOIZUMI Meiro, and curators, such as TAKEHISA Yuu, in which the politics and social relations of Japanese contemporary art can be discussed, along with the provision of practical help in publishing and producing work (activities which are also a mainstay of organizations such as 3331 Arts Chiyoda or BankArt).[51] Tanaka’s own work—which stages experimental, ethno-methodological group interactions around Fluxus-like instructions—has received great acclaim for visualizing the dynamics and dysfunctions of collaboration, as well as the vulnerabilities of the individual in public space in a politically tense, uncertain era. Global curators such as Hou Hanru have described his work in classic modernist terms of critique, as staging “a force of social restructuring . . . [and] resistance to the hegemony of materialist consumption.”[52] Tanaka himself is cool about this kind of political hyperbole, his own discourse on collaboration being closer to that of Grant Kester. Questioning Claire Bishop’s defense of antagonism as a necessity for democratic politics, Tanaka has sought in response to argue that a “one dimensional dichotomy” of antagonistic art opposing the establishment needs to be tempered by alternative methodologies revealing the complexity of participative social situations.[53] On this point, Tanaka, as well as many of the aforementioned pioneers of socially engaged art in Japan, can be read through the central concerns of the international SEA “field.” Together, they may provide vital new input to on-going refinements of the international debate.

Adrian Favell is Chair in Sociology and Social Theory at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom. A 2006-07 Japan Foundation Abe Fellow, he is the author of Before and After Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art 1990-2011 (2012), and has also published essays in Art in America, Bijutsu Techo, Impressions, Artforum, and ART-iT online. He is currently working on a book about “post-growth” art and architecture in Japan. More info: www.adrianfavell.com

Notes

[1] This work has been written with the support of a Toshiba International Foundation (TIFO) grant 2016-17, for the project ‘Islands for Life: Contemporary Social Art and Architecture in Post-Growth Japan.’ It was written as an associate of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Culture, UEA, Norwich. With thanks to Justin Jesty for editorial guidance and for comments from Miwako TEZUKA and Reiko Tomii. Thanks also for collaboration and advice to architect/urbanist Julian Worrall and writer/curator Tamura.

[2] Summarizing the key criteria put forward in Grant Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011).

[3] As apparent from a cursory scan of, for example, Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Paris: Les Presses du Réel, 1998); Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002); Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Conversation in Modern Art (Berkeley, CA; University of California Press, 2004) and The One and the Many (op cit); Claire Bishop, editor, Participation (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 2006); Pablo Helguera, Education for Socially Engaged Art (New York: Jorge Pinto, 2011); and Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London: Verso, 2012). The comprehensive survey volume and exhibition, Nato Thompson, editor, Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012) contains one Japanese artist (out of about 100 presented), Shimabuku, whose social interventions and practice since the 1995 Kobe earthquake would certainly merit discussion here. See Adrian Favell, ‘Shimabuku’, Artforum Critics’ Picks [online] (August 2013).

[4] Kajiya Kenji, “Art Projects in Japan: Their History and Recent Developments,” Hiroshima Art Project 2008, exhibition catalog (Hiroshima, Japan: Hiroshima City University, 2010), pp.161-152. An essential introduction to art projects in Japan is Kumakura Sumiko and the Art Project Research Group, An Overview of Art Projects in Japan: A Society that Co-Creates with Art (Tokyo: Arts Council, 2015), a summary of a complete published report in Japanese. See also the website Tokyo Arts Research Lab, led by Kumakura: http://www.tarl.jp.

[5] Remarkably Kawamata is not widely noted in the context of current SEA debates on collaboration and social improvisation, despite being a global pioneer of the form from his earliest works; see, however, Jonathan Watkins, “Improvisation,” in Kawamata Tadashi, Tree Huts, exhibition catalog (Paris: Kamel Mennour, 2010), pp.42-47.

[6] Quoting a published discussion between Kawamata and KATSURA Eishi in 2003, in Kenji Kajiya, “Art Project and Japan: Examining the Architecture of Art,” translated by Yu NAKAI, in Hiroshima Art Project 2008 (Hiroshima: Hiroshima Art Project, 2009), p.156.

[7] Bishop, Artificial Hells, pp.163-191.

[8] Particularly around the critique of FUJITA Naoya, “Zen’ei no zonbitachi: chiiki āto no shomondai (Zombies of the Avant-garde: the Problems with Regional Art), in Chiiki āto: bigakku/seido/nihon (Regional Art: Aesthetics/Institutions/Japan) (Tokyo: Horinouchi, 2015), pp.11-44. I am grateful for my understanding of these debates to the sociologist SASAJIMA Hideaki.

[9] Two well-researched, skeptical sociological evaluations are: Susanne Klien, “Collaboration or Confrontation? Local and Non-local actors in the Echigo-Tsumari art triennial,” Contemporary Japan vol. 22, nos. 1 and 2 (September 2010), pp.1–25; Sasajima Hideaki, “From Red Light District to Art District: Creative City projects in Yokohama’s Kogane-cho neighborhood,” Cities 33 (2013), pp.77-85.

[10] On this broader global context, see Philipp Oswalt et al., Shrinking Cities (Stuttgart: Hatje Kantze, 2005) and Giacomo d’Alisa et al, De-Growth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (London: Routledge, 2015). Digging back into the earlier cultural studies tradition of Raymond Williams, Society and Culture 1780-1950 (London: Chatto and Windus, 1958), the emergence of a “post-growth” culture may be seen in parallel to the “long revolution” Williams analyzes as latent in the emergence of popular culture against the backdrop of the industrial revolution. See my discussion in “Yanagi Yukinori and the Inland Sea: Demography, Politics and Welfare in ‘Post-growth’ Community Art Projects,” (2014), available online at academia.edu: http://goo.gl/A3mVzs.

[11] Following the earlier business studies predictions of Ezra Vogel, Japan as Number One: Lessons for America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1979); Chalmers Johnson, MITI and the Japanese Miracle (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1982).

[12] On these points, see Peter Matanle and Anthony Rausch with the Shrinking Regions Research Group, Japan’s Shrinking Regions in the Twenty-First Century: Contemporary Responses to Depopulation and Socio-Economic Decline (Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2011).

[13] See Adrian Favell, “Visions of Tokyo in Japanese Contemporary Art,” Impressions: Journal of the Japanese Art Society of America, vol. 35 (April 2014), pp. 69-83.

[14] In particular, in relation to the global success of the three best known names of Japanese contemporary art since 1990: Murakami Takashi, MORI Mariko, and Nara Yoshitomo. See YAMAGUCHI Yumi, Cool Japan: The Exploding Japanese Contemporary Arts (Tokyo: BNN, 2005). The trio are typically the only contemporary Japanese artists who appear in popular Taschen-type guides to contemporary art. This has not changed since around 2001. For example, Uta Grosenick and Burkhard Riemschneider, editors Art Now: 81 Artists at the Rise of the New Millenium (Köln: Taschen, 2002), or Hans-Werner Holzwarth, editor 100 Contemporary Artists (Köln: Taschen, 2015).

[15] This is a narrative I document in Adrian Favell, Before and After Superflat: A Short History of Japanese Contemporary Art 1990-2011 (Hong Kong: Blue Kingfisher, 2012).

[16] Beginning with Hyper-Archipelago, Aomori Museum of Art (June 9-July 8, 2012) and Artists and the Disaster: Documentation in Progress, Art Tower Mito, (October 13-December 9, 2012), followed by the Aichi Triennale, Awakening, (August 10-October 27, 2013); Roppongi Crossing 2013: Out of Doubt, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, (September 21-January 13, 2014); Arafudo Art Annual in Fukushima prefecture, (2013-14) and Big Sky Friendship, Towada Art Center, (April 19-September 23, 2014). Other notable exhibitions include a long line of group shows at 3331 Arts Chiyoda, see: Nakamura Masato et al., WaWa Project: Rebirth Project, Tokyo: Arts Chiyoda (2012); Yanagi Yukinori’s various Art Base Momoshima shows, including 100 Ideas on Tomorrow’s Island (2012-14); TAKEMINE Tadasu’s Cool Japan, Art Tower Mito (December 22, 2012-February 17, 2013); TERUYA Yūken, Area of Calm, Arts Maebashi (2013); parts of Aida Makoto’s large retrospective, Tensai de gomen nasai (Sorry for Being a Genius) / Monument for Nothing, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, (November 17, 2012-March 31, 2013); http://www.wawa.or.jp; Takashi Murakami: 500 Arhats, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (October 31-March 6, 2016) and Chim↑Pom, Kubota Kenji et al’s brilliant conceit, Don’t Follow the Wind, launched at Watarium, Tokyo (September 19-November 3, 2015), and touring internationally—an exhibition about a “future” exhibition of installations placed in the Fukushima exclusion zone which no one can visit.

[17] Notably, the leading critic of the 1990s, SAWARAGI Noi, has returned prolifically to his post-nuclear “zero Japan” themes, see his regular online writings for the journal ART-iT at: http://goo.gl/wYG3oz. There has also been substantial discussion around the writings of MŌRI Yoshitaka, see: “New Collectivism, Participation and Politics after the East Great Japan Earthquake,” World Art, vol. 5, no.1 (2015), pp.167-186; and Mouri’s former student, FUKUZUMI Ren, see Konnichi no genkaigeijutsu [Marginal Art for Today] (Yokohama: BankArt, 2008) and his work for the Echigo-Tsumari in 2012 and 2015.

[18] I owe this point to philosopher Hoshino Futoshi, who is often in dialogue with artist Tanaka Koki. “After the Social Turn: Socially Engaged Art in East Asia” (2015), mimeo and discussion with author.

[19] As critiqued in the work of Ming Tiampo, Gutai: Decentering Modernism (Chicago, Il: Chicago University Press, 2011); Reiko Tomii, Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (Cambridge: MA: MIT Press, 2016).

[20] The cities of Yokohama and Kanazawa in Japan were notably entrepreneurial in connecting themselves to the global trends launched by the ideas of Richard Florida, Charles Landry et al. See SASAKI Masayuki, “Urban Regeneration through Cultural Diversity and Social Inclusion,” Journal of Urban Cultural Research, 2 (2011), Osaka University [online resource]: http://goo.gl/kQ7rwu.

[21] Author’s discussion with creative arts policy consultant, Yoshimoto Mitsuhiro, November 2015.

[22] For further details, see Kitagawa Fram et al., Art Place Japan: The Echigo-Tsumari Triennale and the Vision to Reconnect Art and Nature (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015), including my essay, Adrian Favell, “Echigo-Tsumari and the Art of the Possible: the Fram Kitagawa Philosophy in Theory and Practice,” pp.142-173.

[23] For the sociological background to this kind of initiative, see: Stephanie Assman, editor, Sustainability in Contemporary Rural Japan: Challenges and Opportunities (New York: Routledge, 2015).

[24] YAMAMURA Midori, Review of Art Place Japan and Echigo-Tsumari, CAA Review [online], (December 15, 2016):. http://goo.gl/sNoqwn.

[25] Nakahara Yusuke, “Portents of a Restoration in the Arts,” in Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, exhibition catalogue (Tokyo: Art Front Gallery 2000), pp.11–13.

[26] Kuroda Raiji, Owarinaki kindai: Ajia bijutsu wo aruku 2009–2014 (Behind the Globalism) (Tokyo: Grambooks, 2014). My thanks here to independent curator Honda Eiko, whose insightful essay presenting Kuroda’s book can be found here: http://curatingcuriosities.tumblr.com/post/109193169092/owarinaki-kindai-ajia-bijutsu-wo-aruku-2009-2014

[27] Reiko Tomii, Radicalism; and “Introduction: Collectivism in Twentieth Century Japanese art,” in Positions: Asia Critique, vol. 21, no.2 (2013), pp.212-267, esp. pp.236-237.

[28] Author’s interviews with Kitagawa Fram, Tokyo (June 22, 2009 and September 30, 2014).

[29] Author’s interviews with Yamano Shingo, Yokohama (July 30, 2012) and Kuroda Raiji, Fukuoka (July 4, 2013).

[30] Author’s interviews with Hoshina Toyomi, Tokyo (July 22, 2012) and Kawamata Tadashi, Paris (July 17, 2013). Interview with Ikeda Osamu, Yokohama (September 21, 2014).

[31] Kawamata Tadashi, Coalmine Project 1996-2000 (Tokyo: Insatsu, 2009).

[32] Yanagi Yukinori, Inujima Note (Tokyo: Miyake Fine Arts, 2010); Yanagi Yukinori, “Art at Large: Art Making in the Long View,” artist talk, Museum of Modern Art, New York (May 3, 2013).

[33] Amy Frearson, “A-art House and C-art house by Kazuyo Sejima,” Dezeen [online magazine] (October 15, 2013): https://www.dezeen.com/2013/10/15/a-art-house-and-c-art-house-by-kazuyo-sejima

[34] I have been an observer-participant at events on Momoshima, with ongoing discussions with the artist since December 2007. See my collaborative work with Eiko HONDA, “One Hundred More Momoshimas,” http://curatingcuriosities.tumblr.com/post/96972616542/100-more-momoshimas.

[35] Play as in the sense developed by the Dutch philosopher Johan Huizinga, and later Constant’s notion, evoked by Yanagi as the slogan for his Art Base Momoshima: “For artists and their collaborators, art here is not the means, but the very end itself. It is the frontline base of a very serious form of play.”

[36] See further discussion on “Ruins” in Ken Tadashi OSHIMA, editor, Arata Isozaki (New York: Phaidon, 2009). Isozaki’s famous statement goes:

“Incubated cities are destined to self-destruct

Ruins are the style of our future cities

Future cities are themselves ruins

Our contemporary cities, for this reason

are destined to live only for a fleeting moment

Give up their energy and return to inert material

All our proposals and efforts will be buried

And once again the incubation mechanism is reconstituted

That will be the future.”

[37] Published as the postscript of Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist, Project Japan (Köln: Taschen, 2011).

[38] Presented at PS1, New York (November 20, 2011-April 23, 2012). See: http://momaps1.org/exhibitions/view/346.

[39] Finger Pointing Worker, Pointing at Fukuichi Live Cam, 2011. Webcam video capture. TAKEUCHI only claims himself to be the “representative” of the worker. See his residency at Arts Catalyst, London (July 7-29, 2016): http://www.artscatalyst.org/kota-takeuchi-residency-and-exhibition-arts-catalyst.

[40] KATŌ Tsubasa, Mitakuye Oyasin (Tokyo: Group Gendai, 2014). An image of this lighthouse event which took place in Iwaki was chosen for the publicity of the University of Washington, ‘Socially Engaged Art in Japan’ conference, see: https://sites.google.com/a/uw.edu/seajapan/home.

[41] See the website http://wawa.or.jp for further details.

[42] My discussion here is largely based on interviews with Nakamura Masato, Tokyo (April 4, 2010 and October 12, 2015). See also the website for the exhibition and talks: http://m.3331.jp/en/; and Favell, Before and After Superflat, pp. 209-220.

[43] See the extraordinary exhibition of his work which inaugurated the gallery space at 3331 Arts Chiyoda: “Where have all these toys come from?,” (July 15-September 9, 2012): http://goo.gl/EKNNRG.

[44] Emily Wakeling, “Masato Nakamura,” Artforum Critics’ Picks [online] (November 9, 2015).

[45] Author’s interview with Nakamura, Tokyo (April 4, 2010).

[46] Paul Schimmel, “Making Murakami” in Paul Schimmel, editor, ©MURAKAMI, exhibition catalog (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles/New York: Rizzoli), pp.53-79. Author’s interview, Los Angeles (May 4, 2009).

[47] I analyze the variable way major artists in Japan of the 1990s have utilized resources to generate large scale projects in Adrian Favell, “Resources, Scale and Recognition in Japanese Contemporary Art: ‘Tokyo Pop’ and the Struggle for a Place in Art History,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society vol. 26, (December 2014), pp.135-153. In this essay I discuss the work of Murakami, Nara, Aida Makoto, OZAWA Tsuyoshi, NAKAHARA Kodai and SONE Yutaka.

[48] Among artists, Mori Mariko and YANAGI Miwa are two rare examples of mid-career female artists with their own organizational modes of achieving large scale work. Though an incomplete list, some of the important female curators and gallerists include Hasegawa Yūko (often credited as the most powerful figure in the Japanese contemporary art world, alongside NANJO Fumio), as well as names such as KAMIYA Yukie, KASAHARA Michiko, KATAOKA Mami, Kobata Kazue, KOIKE Kazuko, KOYANAGI Atsuko, MIKI Akiko, OSAKA Eriko and YAMAMOTO Yuko. To this list could be added the writer MATSUI Midori and the collector ISHINABE Hiroko. Younger rising figures might include: FUJIKI Rika, KIMURA Erika, MIYAKE Akiko, NOSE Yoko, TAKAHASHI Mizuki, Takehisa Yuu, UEMATSU Yuko and URANO Mutsumi. It is important to note as well that within the art organizations discussed, women can be found playing indispensable management roles: for example, MAEDA Rei at Art Front Gallery, Shishido Yumi at 3331 Arts Chiyoda, or AOSHIMA Chiho at Kaikai Kiki.

[49] My thanks for discussions with art historian Midori YOSHIMOTO on this point.

[50] “Revolutionist of the Contemporary Art,” interview with Ushiro Ryūta, Shift, (June 2011) [Online resource]; author’s interview with KUROSE Yohei, Tokyo, (July 18, 2016).

[51] Notably the Artists Guild, founded in 2009. See his collected essays, Tanaka Kōki, Random Directions are Necessary (Tankobon: Tokyo, 2014).

[52] Hou Hanru (2015) “Aesthetics of the Failed? On the work of Kōki Tanaka,” in Tanaka Kōki, Precarious Practice (exhibition catalog), Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle, Berlin (March 26-May 25, 2015), (Ostfildern: Hatje Kantz Verlag, 2015), pp.18-23.

[53] “Rethinking Ethics in Art,” discussion featuring Tanaka Kōki and YANAGISAWA Tami reported in: Artists’ Guild + Arts Commons Tokyo NPO, Our Feardom of Expression and Internalization of Censorship (Tokyo: Torch Press, 2016), p.30.