Delirium and Resistance after the Social Turn

Gregory Sholette

To a degree unprecedented in any other social system, capitalism both feeds on and reproduces the moods of populations. Without delirium and confidence, capital could not function.

– Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (2009)[1]

Art and art-related practices that are oriented toward usership rather than spectatorship are characterized more than anything else by their scale of operations: they operate on the 1:1 scale… They don’t look like anything other than what they also are; nor are they something to be looked at and they certainly

don’t look like art.

– Stephen Wright, Toward a Lexicon of Usership (2013)[2]

In just a few short years the emerging field of social practice has gained a considerable following thanks to the way it successfully links an ever-expanding definition of visual art to a broad array of disciplines and procedures, including sustainable design, urban studies, environmental research, performance art, and community advocacy, but also such commonplace activities as walking, talking and even cooking.[3] Not just another cultural field or artistic genre, social practice is evolving into a comprehensive sphere of life encompassing over a half dozen academic programs, concentrations, or minors at the graduate and undergraduate levels already dedicated to turning out engaged artists, and still more programs in the pipeline (and full disclosure I am part of this pedagogical trend evolving at the City University of New York). Philanthropic foundations, meanwhile, are hurriedly adding community arts related grants to their programming, and major museums are setting aside part of their budgets (primarily from education departments although that seems about to change) in order to produce ephemeral, participatory projects that have the added benefit in a crash-strapped financial environment of being relatively low in cost, of not requiring storage or maintenance, and of generating audience interest in ways that static exhibitions no longer seem to provide.[4] “Art,” writes Peter Weibel, “is emerging as a public space in which the individual can claim the promises of constitutional and state democracy. Activism may be the first new art form of the twenty-first century.”[5]

And yet all of this ferment is also taking place at a moment when basic human rights are considered a state security risk, when sweeping economic restructuring converts the global majority into a precarious surplus, and when a widespread hostility to the very notion of society has become commonplace rhetoric within mainstream politics. In truth, the public sphere, as both concept and reality, lies in tatters. It is as much a casualty of unchecked economic privatization, as it is of anti-government sentiments and failed states. Counter-intuitively, the rise in the number of Non-Governmental Agencies (NGO) does not reveal a healthy social sphere, but more of a desperate attempt at triage aimed at resolving such complex issues as global labor exploitation, environmental pollution, and political misconduct all of which no longer seem manageable within the framework of democratically elected state governance. The contrast and similarity between socially engaged art collectives and NGOs has been noted by Grant Kester, who cites criticisms by the Dutch architectural collective BAVO regarding “accomodationist” practices that only aim to fix local social problems without questioning the system that gave rise to these problems in the first place.[6] My concerns fall along similar lines, except that here in the United States the situation is less easy to parse. A lack of public funding for art, as well as the absence of an actual Left discourse or parties makes it difficult to avoid some level of dependency on the institutional art world.

That a relationship exists therefore between the rise of social practice art and the fall of social infrastructures there can be no doubt. And it begs the question, why art has taken a so-called “social turn,” as Claire Bishop proposes, just at this particular historical juncture?[7] I raise this paradox now, as engaged art practices appear poised to exit the periphery of the mainstream art world where it has resided for decades, often in the nascent form of “community arts,” in order to be embraced today by a degree of institutional legitimacy. The stakes are becoming significantly elevated, and not only for artists, but also for political activists. This is not a simple matter of good intentions being coopted by evil institutions. We are well beyond that point. The co-dependence of periphery and center, along with the widespread reliance on social networks, and the near-global hegemony of capitalist markets makes fantasies of compartmentalizing social practice from the mainstream as dubious as any blanket vilification of the art world. As Fischer puts it, a delirious confidence permeates our reality under Capitalism 2.0, and I would add that contemporary art is simultaneously its avant-garde and its social realism. My response is to propose a détournement of this state affairs by rerouting capital’s deranged affectivity in order to counter its very interests. I would like to say that this is the goal of my re-examination here, which aims to make trouble for the increasingly normalized theory, history and practice of socially engaged art and its political horizon, or lack thereof. I would like to insist that this is an attempt to bring about a system-wide reboot. Realistically though, I hope to at least present an outline for future research, discussion and debate regarding the paradoxical ascent of social practice art in a socially bankrupt world.

Capital and art, two seemingly discrete, even antithetical categories, appear to be converging everywhere we look, from the barren sands of Abu Dhabi where western museum’s help brand patriarchal monarchies propped up by a surplus of petrodollars and impoverished migrant workers, to online subscriber-driven services like the Mei Moses Fine Art Index, which promotes itself as the “Beautiful Assets Advisor” faithfully keeping track of financial returns on art for the .01% super-rich, much as the Stock Exchange does for other types of investors.[8] Perhaps it is no coincidence then that both the Mei Moses Index and the future Louvre Abu Dhabi were rolled out in 2007, just as key economic indicators were falling like dominos across the world banking system. It was also the year Apple announced the iPhone, so that by the end of 2007 some 700 Billion SMS text messages had been sent, setting the stage some would argue for a series of “twitter revolutions,” starting in Iran and Moldavia in 2009, and then later across the Arab world.[9] Books such as Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2007) launched a salvo against Milton Friedman style laissez-faire capitalism, while Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt’s re-theorization of imperialism in their best-selling volume Empire (2001), followed by Multitude (2005), continued to inspire anti-globalization activists in the Global Justice Movement.[10] Still, at this very same moment a combination of dark derivatives, toxic assets, and subprime mortgage tainted hedge-funds were beginning to tank as virtually the entire planet was about learn to speak the “grammar of finance.”[11] “The financialization of capitalism—the shift in gravity of economic activity from production (and even from much of the growing service sector) to finance—is thus one of the key issues of our time,” wrote John Bellamy Foster in a 2007 Monthly Review article, adding prophetically “rather than advancing in a fundamental way, capital is trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of stagnation and financial explosion.”[12] As the journal containing his essay went to print the entire global economy began plunging into a massive, prolonged contraction that is still crippling indebted nations and individual workers today.

Astonishingly, one of the few markets to not only weather the crisis, but which also subsequently exploded in aggregate value, even as the rest of the economy remained in deep recession, was that of fine art. On May 9th, 2008 Sotheby’s sold 362 million dollars worth of modern and contemporary painting including a record breaking Francis Bacon painting triptych. And the sales have not weakened since.[13] It was the same day Fitch Ratings announced they were awarding a subsidiary of Lehman Brothers Holding Inc. an ‘A,’ for a positive financial outlook. Four months later Lehman initiated the largest bankruptcy filing in U.S. history, sending the stock market into a sustained sequence of unprecedented capital loses.[14] Expectations were high that the art market would follow this downward trend, just as it did after the 1987 “Black Monday” crash. And initially, the art market did indeed take a hit, with prices for such seemingly stable assets as Impressionist and post-Impressionist painting dropping as much as much as 30% in value by the end of 2008.[15] Then something unexpected took place. Sales of art stabilized and began to rise again, so that by 2013 the global art market grossed €47.42 billion in sales, the second most prosperous year on record since 2007.[16] Since then art sales have continued their dramatic and unprecedented boom even as the economic crisis continues to plague most of the world’s nations. One result of art’s cultural potency has been the mutation of works of art themselves, a process in which a relatively fixed capital asset such as a Jackson Pollock painting owned by a well-heeled society elite a few decades ago has today morphed into an investment instrument capable of being bundled together with other assets by clever hedge fund managers. This goes well beyond the merely entrepreneurial marriage between art and commerce exemplified by, say, Jeff Koons who has licensed his metallic, balloon dog brand for use on H&M handbags. This financialization zeitgeist is shifting art all the way down to what might be thought of as its ontological level. Artist and theorist Melanie Gilligan goes so far as to suggest that even the production of artistic work is beginning to resemble a type of finance derivative, which rather than seeking to generate new forms or new values instead depends “on the reorganization of something already existing.”[17]

Pervasive financialization has also led to the un-concealing of art’s political economy. Eyes wide open, the legions of largely invisible artists and cultural workers so fundamental to reproducing what Julian Stallabrass sardonically dubbed Art Incorporated as far back as 2004 are starting to doubt their professional allegiances. We now see in high relief what has always been right in front of us all along: the thousands of invisible, yet professionally trained artist service workers –fabricators, assistants, registrars, shippers, handlers, installers, subscribers, adjunct instructors– who are necessary for reproducing the established hierarchies of the art world. This socialized dark matter is now impossible to unsee, as criticism of the top-heavy distribution of compensation endemic to the field of artistic production intensifies. Some artists are even beginning to organize.

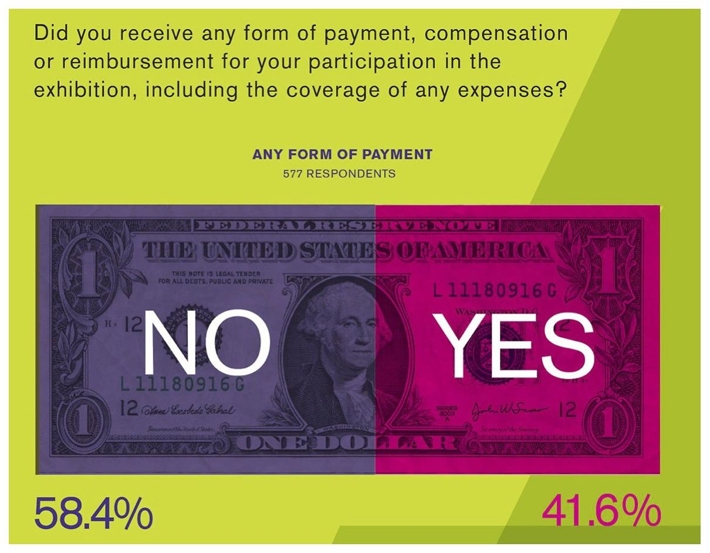

The business-as-usual art world is now facing not one, but two mutinous tendencies. The first involves demands that the art industry be regulated in order to assure a more equitable allocation of resources for all concerned. The other involves escape. Examples of the first tendency include recently formed artists’ organizations such as Working Artists for the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), BFAMFAPHD, ArtLeaks, Gulf Labor Coalition, Debtfair, Art & Labor (both offshoots of Occupy Wall Street), and a new Artist’s Union being organized in Newcastle, England. These micro-institutions collectively assert moral and sometimes also legal pressure on the art industry demanding that it become an all around better citizen.[18] Redressing economic injustice in the art world, including the 52,035 average dollars of debt owed by art school graduates has also been the topic of recent conferences including “Artist as Debtor,” the 2015 College Art Association panel entitled “Public Art Dialogue” Student Debt, Real Estate, and the Arts, and “Art Field As Social Factory” sponsored by the Free/Slow University in Warsaw Poland in order to address the “division of labor, forms of capital and systems of exploitation in the contemporary cultural production.”[19]

The second reaction by artists to the current crisis involves exiting the art world altogether, or at least attempting to put its hierarchical pecking order and cynical winner-takes-all tournament culture at a safe distance.[20] For many artists the primary means of achieving this is withdrawal, or partial withdrawal, which sometimes involves turning to social and political engagement outside of art.[21] In theory, not only is it difficult to monetize acts of, say, artistic gift giving or dialogical conversation, two commonly practiced operations that typify socially engaged art, but also by forming links to non-art professionals in the “real” world one establishes a sense of embodied community quite apart from and affectively far richer than anything possible within the hopelessly compromised relations of the mainstream art world.

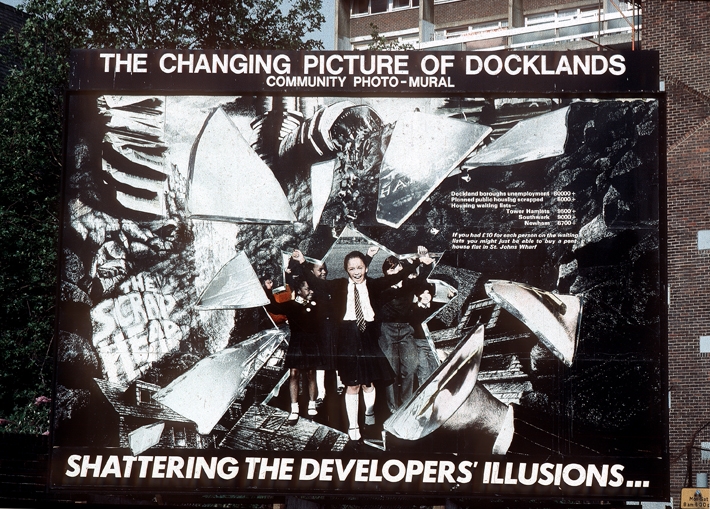

In truth, collectively produced art and community-based art have been around for decades. Beginning in the 1970s the British Arts Council began to funnel support to muralists, photographers, theatre troupes and other cultural and media workers operating outside the studio in urban and rural public settings. A similar dissemination of government resources took place in the US under the US Department of Labor’s Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) as well as through National Endowment for the Arts funding. Some of this public support gave rise to artist’s run alternative spaces. It also helped establish artists working within labor unions, impoverished inner city neighborhoods, prisons, geriatric facilities and other non-art settings. Exactly what makes current, more celebrated forms of social practice art distinct from these previous incarnations of community art is hard to pinpoint, although four things do stand out.

One difference is the move away from producing an artistic “work,” such as a mural, exhibition, book, video, or some tangible outcome or object, and towards the choreographing of social experiences itself as a form of socially engaged art practice. In other words, activities such as collaborative programming, performance, documentation, protest, publishing, shopping, mutual learning, discussion, as well as walking, eating, or some other typically ephemeral pursuit is all that social practice sometimes results in. It’s not that traditional community-based art generated no social relations, but rather that social practice treats the social itself as a medium and material of expression. Blake Stimson and I began to intuit this shift in 2004. Writing about what we then perceived to be an emerging form of post-war collectivism after modernism,

This [new collectivism] means neither picturing social form, nor doing battle in the realm of representation but instead engaging with social life as production, engaging with social life itself as the medium of expression. This new collectivism carries with it the spectral power of collectivisms past just as it is realized fully within the hegemonic power of global capitalism.[22]

Theorist Stephen Wright similarly insists in his recent book Toward a Lexicon of Usership that contemporary art is moving beyond the realm of representation altogether and into a 1:1 correspondence with the world that both we, and it, occupy.[23] Before returning to these provocative claims, let me offer one other, less sensational contrast between social practice art and community-based arts. The mainstream critical establishment of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s treated community-based art either with indifference or derision. It was a level of scorn that community artists returned in spades. Driven by populist ideals as much as contempt for art world glitterati, community artists frequently turned their backs to the established art world, and still do. On those rare occasions when a “serious” critic did “stoop” to address this “unsophisticated” art four issues typically arose.

First, while community artists who were, as often as not, white, middle-class and college educated, might collaborate with inmates to make “prison art,’ or choreograph dances with geriatric patients, or train inner-city kids to make paintings and sculpture, thereby bringing pleasure and culture to the underserved, they were also, it was argued, undermining art’s historically established autonomy from the everyday world. As far as “highbrow” art historians go, this is akin to wearing a large target on your back at a shooting range. Art’s allegedly unique state of independence from life has, at least since the time of Schiller and Kant, permitted artists a singular type of freedom from useful labor. It is this purposeless purpose that allows artists to operate in opposition to the banality of the everyday as well as what Theodor W. Adorno and Herbert Marcuse later designated as monopoly capitalism’s “totally administered society.” That is to say, artistic work retains an ability to withdraw from the everyday world’s profaned, degraded routines only by keeping a measured, critical distance from it. By attempting to narrow the gap between art and society, community artists do exactly the opposite. Sin number one.

Second, community arts appear to substitute artist-generated services for genuine public services, thus reforming rather than fundamentally transforming offensive political inequalities that have only grown more extreme over the past thirty years, thanks to the anti-government policies of neoliberal, deregulated capitalism. Following the collapse of the world financial market this “replacement strategy” of artist service providers for actual social services seems to have accelerated in the US and UK in particular as governments look for ways to cut public spending. As we well know, artists work cheap. Unionized social workers, educators, therapists do not. In addition, point three, community-based art practices run the risk of ensconcing the contemporary artist as some sort of profound, revelatory change agent, or as Grant Kester perceptively wrote, an aesthetic evangelical.[24] And finally, who says community is a good thing? Of course this depends on your definition of community but the world is full of tyrannical “communities,” where difference, mental, physical, sexual, leads to expulsion or worse. Profano Numerus Quattuor. Nevertheless, all of these charges can just as easily be applied to social practice art today, and yet it seems to be the unconfirmed major contender for an avant-garde redux. What has changed?

Maybe it was Nicholas Bourriaud’s promotion of Relational Aesthetics in the 1990s that began the rehabilitation of community art? Recall that the celebrity curator insisted artist Rirkit Tirivanija’s gallery-centered meal sharing established a new, socially participatory paradigm for post-studio artistic practices. It was a claim the art world uncritically devoured. Or perhaps it was the expanding network of artists developing ephemeral actions, research-based public projects, and impermanent installations as a response to an ever-shrinking stock of large urban studio spaces? There is still a fifth possibility: the loss of no-strings-attached public funding for art institutions after the 1980s may have ironically brought about a popularization of museum programming by forcing institutions to seek out more interactive, spectacular public events. None of these scenarios disregards the sincerity of artists who seek communal experiences or socially useful applications for their work. The question here is what accounts for the positive reception of social practice art today, as opposed to the negative reception of its close kin, community art, only a decade or so ago? One way or the other, it seems that by the early 2000s we find previously widespread art world resistance to socially engaged art practices eroding, though always selectively, so that now in 2015 the social turn is spinning full-throttle.

It is an inversion of artistic taste so abrupt that it reminds me of the late 1970s when painters still earnestly grappling with Greenbergian “flatness” discovered a decade later that it was an artistic “problem” that had simply vanished as a jubilant, and often juvenile 1980s art scene embraced figurative painting, decorative crafts, and even low-brow kitsch, all of which were the bane of most modernist aestheticians. Likewise, drawbacks once dismissively associated with community-based art are just as fugitive today, vanishing in a puff of smoke like the undead at sunrise. Aside from an occasional critic like Ben Davis who insists that “the genre of “social practice” art raises questions that it cannot by itself answer,” most graduating MFA students today feel obliged to join an art collective and attempt to connect themselves to communities which are not traditionally part of the fine art world.[25] If anything, the focus on socially engaged art by the mainstream art world has actually eclipsed, rather than illuminated the many individuals still active in community arts, turning long simmering resentments once directed at the art world establishment into charges of appropriation and colonization.[26]

Davis may be right about the blindness of social practice art to its own preconceptions. Still, the fact that so many young people today are desperately seeking to redefine the way they live from the point of view of both environmental and social justice adds an impressive robustness to this cultural phenomenon. Art seems to be the one field of recognized, professional activity where a multitude of interests ranging from the aesthetic to the pragmatically everyday co-exist, a state of exception that led to artist Chris Kraus’s musings on what she calls the ambiguous virtues of art school,

Why would young people enter a studio art program to become teachers and translators, novelists, archivists, and small business owners? Clearly, it’s because these activities have become so degraded and negligible within the culture that the only chance for them to appear is within contemporary art’s coded yet infinitely malleable discourse.[27]

Socially engaged art practice is becoming such an attractive and paradigmatic model for younger artists that it seems to fulfil Fredric Jameson’s proposition that particular historical art forms express a social narrative that paradoxically, “brings into being that very situation to which it is also, at one and the same time, a reaction.”[28] At first glance, this seems like the answer to my initial question: why is socially engaged art advancing at a moment when society is bankrupted? Because, with due respect to Jameson, it resolves intolerable contradictions in the actual world. But while this explanation may have been applicable to Relational Aesthetics, it seems inadequate just a decade or so later with regard to social practice. For Jameson, the work of art remains a categorically discrete entity, a novel, building, performance or film framed within a specific historic, cultural and institutional context. It is, in other words, the privileged site where the work of hermeneutic textual interpretation takes place. What if social practice art has already successfully inverted normative representational framing as art, flipping inside out our spectator-based distance from the world so that now everything is outside the frame and nothing remains inside?

In Wright’s 1:1 thesis, the practice of socially engaged art would then simply constitute the social itself, emerging into the everyday world as a set of actual social relations or commonplace activities, and not as a deep critical reflection or aesthetic representation of society or its flaws. This is different from a Kaprow/Beuys/Fluxus tactic of inserting anti-art into the everyday world. 1:1 art just becomes redundant by providing “a function already fulfilled by something else.”[29] Neither does Wright’s model conform to Shannon Jackson’s notion that such heteronomous social activities might be folded into a neat, academic framework via performance studies.[30] If these emerging practices interact with social life by producing the social itself, then they are neither an experimental trial, nor a performance, nor even a rehearsal for some ideal society. In fact the term practice would be a misnomer. Leading to several complicated consequences.[31] First, redundant, 1:1 social practices are subject to all of the legal, economic, and practical consequences of any other real-world activity. Take Pittsburgh-based Conflict Kitchen that specializes in serving food from countries that the United States is in conflict with including North Korea, Iran, and Venezuela. When they presented a Palestinian menu last year someone sent the artists a death threat, forcing them to shut down under police protection for several days. Yes, paintings and other artistic projects have drawn hostility to themselves or their authors due to what or how they represent someone or some nation or idea, but in this instance, does it really make sense to defend Conflict Kitchen as an art project with a guaranteed first amendment right to free speech when the laws protecting commercial business, which is from a legal perspective CK is, are already enough? Conversely, first amendment rights would not prevent this culinary art project from becoming liable for, say, a food born illness, should one be accidentally transmitted to a customer.[32] Operating in the real world also presents learning challenges for socially engaged practitioners trained by artists who paint, and draw, and make installation art in the isolation of their studio. Commenting on the challenge of this autodidactic learning curve, artist Theaster Gates explains with genuine surprise that while working on his Dorchester housing restoration projects in Chicago “I never learned so much about zoning law in my life.” To anyone other than an artist trained to deal with the representations of things, but not things themselves, gaining practical knowledge about zoning laws would have been self-evident.[33]

Second, by working with human affect and experience as an artistic medium social practice draws directly upon the state of society that we actually find ourselves in today: fragmented and alienated by decades of privatization, monetization, and ultra-deregulation. In the absence of any truly democratic governance, works of socially engaged art seem to be filling in a lost social by enacting community participation and horizontal collaboration, and by seeking to create micro-collectives and intentional communities. On the surface, it’s as if they were making a performative proposition about a truant social sphere they hope will return once the grown-ups notice it’s gone missing. If however they are instead incarnating the remains of society as I am suggesting, then the stakes are radically different, for better and for worse. It is for better when social practice and community-based artists engage with the political, fantastic, or even resentful impulses of people, a process that can lead to class awareness or even utopian imaginings much as we saw with Occupy Wall Street. It is for the worse when the social body becomes prime quarry for mainstream cultural institutions and their corporate benefactors who thrive on deep-mining networks of “prosumers” bristling with profitable data.[34] Even the normally optimistic theorist Brian Holmes gloomily warns us that “the myriad forms of contemporary electronic surveillance now constitute a proactive force, the irremediably multiple feedback loops of a cybernetic society, devoted to controlling the future.[35]

One way to grapple with the present paradox of social practice art’s predicament is to turn to the archive of past projects and proposals –including those that succeeded and those that failed– in order to reappraise certain moments within the genealogy of socially engaged art that might have unfolded differently. To find vestiges and sparks suggesting unanticipated historical branches that may have sprouted off into directions that would possibly be less vulnerable to the pressures for normalization, institutionalization and administration. One of these significant junctures took place shortly before two world-altering historical occurrences–the global financial crash of 2007/2008 with its devastating economic effects and the widespread surveillance, even criminalization of the electronic commons. The year 2004-2005 sits at a point were the counter-globalization movement was invisibly beginning to falter, and immediately after unprecedented global peace demonstrations distressingly failed to stop the illegal, US-led invasion of Iraq. It precedes the full disclosure of the emerging national security state complex of today. Nevertheless, these realities had yet to fully sink in as artists, activists and intellectuals remained captivated by the utopian potential of new communications technologies and the “people-power” that seems to have led to the downfall of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European empire. Coming into focus was a group of tech-savvy, cultural activists who’s bold hit and run interventions sought to undermine established authority by literally upending public spaces and turning the mainstream media’s resources against itself.

Artists Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere of the group neuroTransmitter put it this way:

For us this a was moment of heightened media art and activism. Artist were extending the possibilities of new technologies and re-inscribing the use of old media forms. It was a time of innovations in technology and communications media, yet we were interacting in physical space rather than through social media… where we both interacted on the street level as well as in the air.[36]

Decidedly non-ideological in outlook (other than an occasional nod of approval towards the Left-libertarian Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) of Chiapas Mexico) tactical media interventionists dismissed organized politics.[37] Some went so far as to castigate past efforts at achieving progressive political change describing the utopian aims of the New Left and May 68 as “vaporware”–a derogatory term used for a software product that while announced with much fanfare, never actually materializes. Geart Lovink and David Garcia argued that tactical media activism sought to hold no ground of its own; instead merely seeking to creatively interrupt the status quo with determined, short-terms acts of public sensationalism and cultural sabotage.

Our hybrid forms are always provisional. What counts are the temporary connections you are able to make. Here and now, not some vaporware promised for the future. But what we can do on the spot with the media we have access to.[38]

In truth, Tactical Media benefitted from a particular historical opening, a quasi-legal loophole that existed before the heavily policed, privatized public sphere emerged full-blown, with its round-the-clock electronic surveillance closing down outlets for resistance, including the kind of critical gaps exploited by more militantly engaged political artists such as Critical Art Ensemble as I will discuss below. In other words, the illegal status of distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks clandestinely carried out by hacktivist groups such as Anonymous in recent years were still in a gray zone into the early 2000s. In 1998 Ricardo Dominquez and Electronic Disturbance Theater designed a pro-Zapatista virtual sit-in platform aimed at overloading and crashing websites belonging to the Mexican Government.[39] But in 2010, University of California Campus Police investigated Dominquez for a tactical media type application he devised that would assist undocumented immigrants crossing the Southern US border.[40] This was also before some forms of social practice art began to attract the attention of mainstream cultural institutions.

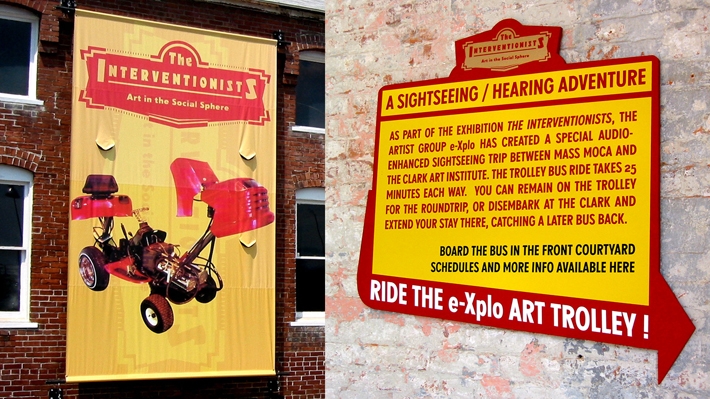

The second half of this essay focuses on this tactical media moment as it was presented in the 2004 exhibition The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere, organized for the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) by their recently hired curator Nato Thompson. The show was dedicated to artists or artists’ collectives who explicitly conceived of art not as an object of contemplation for a passive spectator but as a sharable set of tools for bringing about actual social change. It also reflected a certain optimism that pivoted on the idea of tactics could be adopted by anyone, not just artists, to improve life conditions. What follows is not intended to serve as a diverting tale of speculative nostalgia. Instead, I hope to put this exhibition forward as one wrinkle in the archive of socially engaged art worthy of re-reading, and possibly rebooting its history. Endeavoring to leverage the euphoric concoction of delirium and confidence Mark Fisher attributes to Capitalism 2.0 for a project of archival redemption, I am reminded of a phrase used by Russian Avant-Garde theorist Viktor Shklovsky. I proceed therefore with the “optimism of delusion.”[41]

II. After the Interventionists

Conceived of and produced for the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), curator Nato Thompson’s 2004 exhibition The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere, drew on two precedents: Mary Jane Jacob’s 1992-1993 Chicago-based public art project Culture in Action, and the Détournement or creative “hijacking” of daily life proposed by the Situationist International in the 1960s. It also sought to make a self-conscious break with past attempts to exhibit politically charged contemporary art in a museum setting. Thompson’s curatorial statement compares “the sometimes heavy-handed political art of the 1980s” with his selection of interventionist practitioners who he insists had begun to carve out compelling new paths for artistic practice, coupling hardheaded politics with a light-handed approach, while embracing anarchist Emma Goldman’s dictum that revolutions and dancing should never be separated from each other.[42]

This was no gray on gray presentation of “message art” intended to dutifully instruct its audience about political realities, any more than its content pointed to some romantic socialist vaporworld. Instead a visitor to MASS MoCA was confronted with a zoo-like menagerie of “magic tricks, faux fashion and jacked-up lawn mowers,” packed into the museum’s plaintive post-industrial expanse like a sideshow for activists. Rather than didactic lecturing these projects agitated for social change through ironic critiques, overt lampooning, and subtle co-optations of mainstream media and culture cunningly disguised as the real thing. Artist Alex Villar leaps over fences, scales brick facades and squeezes himself into cracks between tenement buildings, temporarily occupying overlooked urban spaces while performing his own Situationist-inspired version of Parkour, the Spanish collective YOMANGO display fashion accessories for magically making “objects disappear,” (i.e. shoplifting with style), and a member of the Danish group N55 rolls a mobile floating unit down a city street demonstrating the Snail Shell System, a low-cost mobile dwelling useful for transportation and providing “protection from violence during demonstrations.”[43] Something subversive pervaded all of these varied works, though exactly what direction this dissidence pointed towards was fuzzy at best.

If the political identity of these interventionist activists was intentionally difficult to pin-down, the exhibition certainly proved something else, something that most previous displays of socially engaged art had not attempted: it returned a sense of wonder and surprise to oppositional culture. Subterfuge could be fun. Unfortunately, this aspect of the exhibition’s message was easier to take-away as a sound bite than its critical intent. Despite being on view for over a year (May 2004 to March of 2005) The Interventionists received no in-depth reviews, though a one-sentence recommendation for holiday travelers did appear in the New York Times, in which the show was cheerfully described as full of “pranksters and fun politically motivated meddlers.”[44] The absence of serious, critical response cannot be blamed entirely on the lack of familiarity with Nato Thompson, still an untested curator, or with the exhibition’s off-the-grid location in rural New England. Nor was the carnivalesque enthusiasm that unapologetically permeated The Interventionists a reason for this dismissal. After all, a substantial theoretical discourse already existed for this kind of art, online and in Europe, but its authors, including Gene Ray, Brian Holmes, Rozalinda Borcila, Geert Lovink, Marcelo Exposito, Gerald Raunig, Marc James Léger and Stephen Wright among others, then, as now, have limited impact on cultural discourse in the US. The failure of any critic to develop a substantial political and aesthetic analysis of The Interventionists is unquestionably a lost opportunity, especially when one considers the impoverished state of such criticism even up to today. Still, the exhibition managed to demonstrate two things above all. First that a thriving group of contemporary artists in 2004 considered social, political and environmental issues paramount to their practice, and second, that their critique could be delivered through the kind of stimulating visual format audiences of contemporary art had come to expect. Even so, there are two overlooked dimensions of The Interventionists more relevant to my argument still in need of excavation.

MASS MoCA’s sprawling labyrinth of rooms and obsolete industrial apparatus appealed then, as it does today, to vacationers grown tired of Happy Meals and theme parks and searching for that off-beat family experience, but one that promised at least a modicum of educational nourishment. On the occasion of The Interventionists a trip to the museum delivered something extra, a spectacle of imaginative dissidence whose quintessential onlooker was not the art world elite, but instead these same “holiday travelers,” whose demoralized collective unconsciousness theorist Michel De Certeau would call the murmur of the everyday. This was no coincidence. Thompson cut his curatorial teeth co-producing a weekend of guerilla-style street actions in Chicago under the rubric The Department of Space and Land Reclamation or DSLR. Gleefully bringing together graffiti, agit-prop posters, hip-hop, illegal street art and impromptu public actions, DSLR’s bottom-up informality simultaneously paid homage to and deconstructed Mary Jane Jacob’s landmark 1993 public exhibition Culture in Action, all the while turning a blind-eye towards the city’s more art savvy neighborhoods. From gigantic balls of trash rolled down Michigan Avenue at lunch hour by men and women dressed up as sanitation workers to anonymous public sculptures attached to traffic signs and absurd performances including a sofa tagged “Please Loiter” plopped down casually on the sidewalk, DSLR was about as disconnected from the gaze of the art world as one could get in 2001.[45]

No one would argue that MASS MoCA was then or is now disconnected from the contemporary art world, though there is a definite allure generated, even perhaps cultivated, through the museum’s measurable distance from the mainstream art world that is quite unlike that of Dia Beacon’s manageable proximity to New York City.[46] This slightly offbeat appeal extends to the type of administered culture found within MASS MoCA, bringing me to my second point. The Interventionists and its venue benefitted from a symbiotic tension that drew on the exhibition’s rebellious, Situationist-inspired references, as much as it did from the unusual institutional history of MASS MoCA itself. It was self-made cultural entrepreneur Thomas Krens who conceived of MASS MoCA during the economic upturn of 1984. By sidestepping traditional models of noblesse oblige in which those who “own” high culture generously lend their artistic property to public institutions in order to enlighten the masses, Krens developed a business model that linked a growing interest in contemporary art with the economic resuscitation of North Adams, a former manufacturing town that had fallen into economic decline along with other industrial centers in North America. Strategically located in the bucolic border region where Massachusetts meets Vermont, but also relatively close to New York City with its surplus of sophisticated art consumers and art producers, Krens saw his vision as altogether win-win. Then came the collapse of the savings and loan bubble in 1987. Plans for MASS MoCA were put on hold for over a decade. In 1999, the museum finally opened its doors just one year before the next bubble, the so-called dot.com bubble, also exploded sending a pre-Occupy generation of creative workers into states of resentment and near-desperate panic.

At this point Krens had been appointed director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New York City, and soon became the architect of an expanding cultural franchise. Branch museums were established in Berlin, Spain, and Las Vegas, with the latest expansion planned for 2017 in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, an undertaking that has generated substantial public controversy due to the poor labor conditions of the UAE. Krens was also the first director of a major art museum to hold a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) rather than a degree in art historical scholarship. This last detail becomes more interesting when one considers the nature of Mass MoCA. Lacking a substantial collection of officially sanctioned art objects the museum plays host to relatively long-term, temporary exhibitions and shorter-term performance events that situate it somewhere between a European Kunsthalle and a Cineplex. Given Krens’s background it is not surprising that the orthodox concept of an art museum has been partially deconstructed at Mass MoCA. Nor is it unusual to find the traditional role of the curator as one who cares for the well being of cultural treasures reinterpreted as someone who selects, cultivates and produces projects that combine artistic seriousness with visual pageantry. Notably, Nato Thompson himself was hired by the museum without an advanced degree in art history, but instead with a Masters in Arts Administration from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Though, what would have proven a professional deficit for a curator at other large cultural institutions, likely afforded Thompson certain tactical advantages within the hybridized institutional geography of MASS MoCA. There is also an amusing irony here when one considers the intersection of these two incongruous, though equally unorthodox, models of cultural programming: MASS MoCA’s dedication to “deconstructing” the classical idea of the art museum so as to rebrand it a sensational destination for tourists, and The Interventionists unapologetic rejection of institutional critique in favor of an eye-popping primer showcasing the subversive possibilities of Tactical Media as “useful” art.

In the decade following The Interventionists numerous academic conferences, publications, and programs began to engage similar, Situationist-inspired themes, as debates about short-term tactics versus strategic sustainability and artistic instrumentality versus aesthetic value emerged, or rather re-emerged, often recapitulating similar or even identical artistic passions from key moments in avant-garde art history. Meanwhile, the exuberantly designed exhibition catalog–which I co-edited with Thompson–rapidly went into multiple reprints, most likely keeping pace with a renewed interest in conceiving of art as an instrument for social change. And while the counter-globalization movement began to lose energy after 2004, the World Social Forum, an international policy initiative dedicated to countermanding neo-liberal hegemony, drew thousands of participants to Porto Alegre, Brazil and other locations in the “Global South.” In 2004 the forum’s host city was Mumbai, India, and those who gathered collectively asserted: “another world is possible.” As if echoing back from a reconverted electronics plant in the winding hills of New England half a world away The Interventionists seemed to respond yes, and by the way, “another art world is also possible!”[47]

Viewed in this context The Interventionists coincided with a broader sea change already under way within contemporary art. Not only were many privileged cultural practitioners beginning to raise questions about the social purpose of their professional activities, but the mainstream art world itself was poised to embrace a more performative, participatory, and at times ephemeral artistic experience prefigured by watershed moments such as Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11 in 2002. Arguably it is this very shift away from displaying art objects towards generating experimental platforms for discourse and research-based practices that have opened up a legitimatizing space for social practice art today. Nevertheless, there was nothing predetermined about the path leading from an exhibition of tactical media troublemakers at MASS MoCA, into the white walls of MoMA or the Tate Modern.[48] Furthermore, if we construe Thompson’s own tactics as being at least in part a pointed response to Nicolas Bourriaud’s incipient concept of Relational Aesthetics, which similarly celebrated everyday social activity but explicitly rejected overt political content or any self-awareness of artistic privilege, then at least one alternative trajectory for social practice art suggests itself. In this scenario art would still engender social interaction, but it would do so without severing such experimentation from a radical critique of either post-Fordism or the deregulated micro-economy of the contemporary art situated within it. But there is another, darker reason The Interventionists might be a significant nodal point for re-thinking the archive of social practice art and its genealogy.

Just prior to the exhibition opening and thanks to sweeping legislation made available by the post-911 Patriot Act, a Federal Grand Jury began delivering subpoenas to the friends, colleagues and members of Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) as FBI agents confiscated materials the group planned to use for its MASS MoCA installation Free Range Grains. The project involved a DNA sampling apparatus that CAE hacked in such a way as to allow visitors to “home-test” for genetically mutated fruit and vegetable genes already circulating within the US food supply. Typical of CAE’s practice the goal of Free Range Grains was to focus pubic attention on the intentionally inconspicuous proliferation of government and corporate control over a commons fast disappearing thanks to unfettered privatization. Consider for example, a previous CAE installation in which the artists tried to deploy counter-biological agents against Monsanto’s genetically modified Roundup Ready seed stock in an attempt—mostly symbolic—to deprive the agricultural giant of its near-total monopoly over US corn, flax, and soybean production.[49] When CAE co-founder Steve Kurtz was falsely accused by a secretive Grand Jury of bio-terrorism in the weeks leading up to the exhibition the groups MASS MoCA installation materials were seized by the FBI as evidence. Undaunted, curator Nato Thompson and museum director Joe Thompson (no relation) arranged for a facsimile of the project to be placed on display along with a set of informational text panels outlining both the events that had just taken place, as well as the sequestration of CAE’s equipment by the government. In fact this incident and the subsequent pubic ordeal of Kurtz and his co-defendant Robert Farrell received more press attention from the art world and mainstream media than did the exhibition itself.[50]

CAE’s predicament also provided a singular opportunity for socially engaged artists to reconsider what the stakes of their practice were within a broader conception of politics. Sometime around 9PM on May 29th, 2004, about fifty people, many of them engaged artists who were attending the opening of The Interventionists, gathered behind the museum’s main entrance hall. Spread by word of mouth, the objective of the emergency meeting was to develop a coordinated, collective response in Kurtz’s defense. Several of those present had already been issued subpoenas to testify before the Grand Jury, or face imprisonment. However, the discussion that ensued quickly divided into two camps: Kurtz supporters who argued for a pragmatic vindication of the artist based his defense on the artist’s right to free speech under the first amendment, and those hoping to spotlight the investigation’s underlying agenda, which, hinged it was asserted, on George W. Bush’s government’s efforts to stifle political criticism and criminalize “amateur” scientific research carried out by artists, activists, and environmentalists. The late and gifted Beatrice De Costa who was had already been subpoenaed, articulated support for the second, long-range view pointing out that a collective response to accusations should focus on a broader set of rights. Nevertheless, the constitutional defense won out.[51] Four years later after much effort and expense Kurtz was finally exonerated when a federal judge refused to allow the government’s case to go to trial for lack of evidence.

Which brings me to a final point regarding these archival musings. With so many practitioners of tactical media and activist art present for the opening of The Interventionists there was an exceptional organizational opportunity opened up for envisioning a broadly conceived and theoretically nuanced genus of socially engaged art. Ironically, CAE’s misfortune might have jump-started a social practice future in which the proven effectiveness of tactical media complimented, rather than eclipsed, a strategic, long-range vision of political transformation. If another art world was possible in the Spring of 2004, ignition failed. Maybe that was inevitable. And yet, it begs the question. Did the CAE incident inadvertently scrub clean more militant forms of art leaving a more manageable strain of socially engaged art behind?[52] Or was the very lack of a broader, strategic political view also to blame? To put this differently, is vaporware really such a bad thing? After all, some version of collectivism operates within even the most battered social terrain. The question is: what does that collective project look like. Stimson puts it this way,

there are only two root forms of collectivist practice—one based in political life and the state and another in economic life and the market—and our time is marked by a historical shift from a greater degree of predominance for the first to an increasingly influential role for the second.[53]

How might our narrative about social practice art collectivism be imagined differently, or perhaps better yet, how can it be shifted away from the market-based notion of “community as consumer-based demographic” that often, surreptitiously dominates it? And yes, we are talking about conscious political resistance, which may ultimately come from any number of unlikely places. It might, for example, involve a process of engagement as disengagement, something akin to Wright’s notion of escaping through a trap door.[54] Or perhaps it will emerge as John Roberts’s proposes in the form of artistic communization?[55] The recent national demonstrations focusing on police violence against people of color and the unexpected success of the Leftwing Syriza party in Greece, also suggest possible pathways to politicized collectivism. But it could also involve less savory outcomes such as the mobilization of Nietzschian ressentiment, something that we can see already visible in Greece’s far right wing party Golden Dawn, Ukraine’s Svobada, France’s National Front, or even some factions of the United State’s Tea Party Patriots. It would also be a mistake to overlook the fact that these same political, technological, and economic shifts that gave rise to neoliberal enterprise culture also played midwife to numerous process-oriented, self-organized, collective art organizations as previously stalwart barriers between artist and audience, artist and curator, and artist and administrator began to blur and blend.

One result is that cultural institutions now resemble components of a “system” that swap and amplify cultural capital, rather than spaces where rare things are collected, guarded and cared for. It’s no surprise therefore, that Thompson’s approach to The Interventionists embodied many of these same unresolved contradictions, or that historical contingencies determined which of these threads would prevail and which would be suppressed. Writing about the Museums Quartier in Vienna at about the time as The Interventionists Brian Holmes observed that, “the welfare states may be shrinking, but certainly not the museum. The latter is rather fragmenting, penetrating ever more deeply and organically into the complex mesh of semiotic production [outside of its walls].” The stage was being set for the current phase of post-Fordist administration and the transformation of cultural institutions into modifiable platforms for staging temporary, project-based installations, spectacles and events. This administrative turn seems to keep pace with a modified neoliberalism in which both risk and regimentation operate side by side, or as Jan Rehmann summarizes “neoliberal ideology is continuously permuted by it opposite: its criticism of the state, which is in fact only directed against the welfare state, flows into an undemocratic despotism, its ‘freedom’ reveals to signify the virtue of submission to pre-given rules.” Either way, the question remains: What loopholes of resistance were lost in and around 2004? Which might still remain? And how will we usefully uncover those that might still be present?[56]

…

In the decade that followed 2004/2005, the massive private appropriation of public capital by self-damaged investment corporations marked a return, already under way since the 1980s, to forms of worker exploitation and precarious inequality typical of capitalism prior to the banking reforms and collective pushback orchestrated by organized labor in the aftermath of the catastrophic 1929 stock market crash. Following the recent financial collapse an optimistic army of young “knowledge workers,” including many artists, probably experienced shock rivaling that of middle class homeowners with foreclosed property. These privileged “creatives” had been assured that Capitalism 2.0 needed their non-stop, 24/7 yield of “out-of-the-box” productivity. Well, apparently not. Then came the high-profile prosecutions of Chelsea (Bradley) Manning, the government targeting of WikiLeaks co-founder Julian Assange, and revelations about National Security Administration spying by whistleblower Edward Snowden. Even the realm of non-market, digital democracy was clearly becoming a target of government regulators, to which we can add the increasing move away from fair use World Wide Web content, and towards the private, corporatization of intellectual property in both physical and http-coded binary form. Nor did the art world provide a refuge for the most challenging forms of tactical media. CAE for example stopped experimenting with bio-art after 2007, and the group has found little purchase in the US art world, traveling to Europe for most of its ongoing research projects.

Today, social practice artists are busy planting herb gardens, mending clothes, repairing bicycles, and giving out assorted life-coaching advice free of charge. Groups of professional designers are improving the “quality and function of the built environment,” in run-down inner-city corridors, categorizing what they do with the avant-gardeish rubric “Tactical Urbanism.”[57] In the Bronx, working class tenants are asked to invite a couple of artists into their homes for dinner. In exchange the artists paint their hosts a still life. Sitting on a sofa everyone is photographed with the painting hanging in the background like a commentary on social values that are too often absent from the skeptical art world.[58] In New York City’s East Village, a funky storefront installation of assembled, found materials highlights the street culture of a gentrifying neighborhood. One artist collaborates with passerby to turn used paper cups into art, as another encourages residents to engage in “critical dialogue” about their precarious future.[59] Artists distribute free beer, hand picked fruit, glasses of ice tea, and home-made waffles to participating members of the public. These gifts are offered up like a sacrifice to some missing deity whose flock has been abandoned.[60] The absent god is of course society itself, defined as a project of collective good, from each according to her ability, to each according to his need. Instead, the community Capitalism 2.0 offers is based on the gospel of mutually shared selfishness, and certainly any attempt at countering such a credo is justified, even participatory waffle sharing, though it must be said here that hell is undoubtedly paved with many good interventions.

To be sure, the argument put forward here does not deny that artists earnestly struggle to change society, even if the art they produce frequently serves, for better and for worse, as a symbolic ameliorative to irresolvable social contradictions. And yet what has changed is the phenomenal aggregation of networked social productivity and cultural labor made available today as an artistic medium, and at a time when society is intellectually, culturally and constitutively destitute. Art, along with virtually everything else, has been sublated by capital, resulting in the socialization of all production.[61] One outcome is that artists are becoming social managers, curators are becoming arts administrators, and academics are becoming tactical urbanistas. Meanwhile, social practice artists collect the bits and pieces of what was once society like a drawer of mismatched socks. Is it any surprise that these social artifacts only seem to feel alive in a space dedicated to collecting and maintaining historical objects (and I am speaking, of course, of the museum)? But in a field that is weakly theorized even in the best of circumstances, art’s “social turn” makes the passage of engaged art out of the margins and into some measure of legitimacy all the more compelling as a matter for urgent debate. Because if art has finally merged with life as the early 20th Century avant-garde once enthusiastically anticipated, it has done so not at a moment of triumphant communal utopia, but at a time when life, at least for the 99.1%, sucks.

What is called for is imaginative, critical engagement aimed at distancing socially engaged art from both the turbo-charged, contemporary art world, as well as from what Fischer calls capitalist realism in the post-Fordist, society of control, a world where “‘Flexibility’, ‘nomadism’ and ‘spontaneity’ are the hallmarks of management.” As nearly impossible as that struggle seems today, if we do not strive for a broader conception of liberation, then we resign ourselves to nothing less than bad faith, while abandoning hopes of rescuing that longue durée of opposition from below that so many before us have endeavored to sustain. Once upon a time art mobilized its resources to resist becoming kitsch. Now it must avoid becoming a vector for data mining and social asset management. Delirium and resistance prevail today, forming an increasingly indissoluble unit, two cogent responses to current circumstances. But it is this same fever that drives us onwards: a persistent low-grade fever for social justice. What remains paramount is recognizing the actuality of our plight, including its paradoxes, while asking how we can be more than what the market says we are. The terrain thereafter is a delirious terra incognita. It is waiting to be mapped. We must get there first.

Gregory Sholette is a New York-based artist, writer and cultural activist whose recent art projects include “Our Barricades” at Station Independent Gallery, and “Imaginary Archive” at Institute of Contemporary Art U. Penn Philadelphia, and Las Kurbas Center, Kyiv, Ukraine, and whose recent publications include It’s The Political Economy, Stupid, co-edited with Oliver Ressler (Pluto Press, 2013) and Dark Matter: Art and Politics in an Age of Enterprise Culture (Pluto Press, 2011). A graduate of the Whitney Independent Studies Program in Critical Theory (1996), he was a founding member of the artists’ collectives Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D: 1980-1988), and REPOhistory (1989-2000), and remains active today with Gulf Labor Coalition. He teaches socially engaged art at Queens College CUNY and Home Work Space Beirut, Lebanon.

Notes

A special thanks to Alan Moore, Erika Biddle, Kim Charnley and Grant Kester for their insights and advice.

[1] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Alresford, England: Zero Books 2009), p.35.

[2] Stephen Wright, Toward a Lexicon of Usership, published on the occasion of the Museum of Arte Útil at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2013. It is also available as a PDF online at: http://museumarteutil.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Toward-a-lexicon-of-usership.pdf

[3] Throughout most of this essay I will use the term “social practice art” to describe the type of cultural production under discussion because this label seems to have gained the widest usage at this point in time. For an interesting hypothesis about the evolution of this terminology see: Larne Abse Gogarty, “Aesthetics and Social Practice,” in Keywords: A (Polemical) Vocabulary of Contemporary Art, October 3, 2014, available online at: http://keywordscontemporary.com/aesthetics-social-practice/

[4] In the past three or four years alone several East Coast institutions of higher education have added some level of social practice or community oriented arts curricula to their offerings. Along with Queens College CUNY this includes NYU, SVA, Pratt, Parsons and Moore College of Art in Philadelphia. Regarding the philanthropic turn towards social practices, in 2014 the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation announced what they describe as a “game changing” $100,000 grant category called Artist as Activist which is aimed at supporting individuals who address “important global challenges through their creative practice”: http://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/grants/art-grants/artist-as-activist. There is also The Keith Haring Foundation which in the same year provided Bard College with $400,000 to support a teaching fellowship in Art and Activism at the school http://www.bard.edu/news/releases/pr/fstory.php?id=2516, and just a few years ago in 2012 an entirely new foundation calling itself A Blade of Grass tells us that it “nurtures socially engaged art” http://www.abladeofgrass.org/. And the Education Departments at the Museum of Modern Art and Guggenheim Museum sponsor socially engaged art projects with the latter hosting the think tank/community center known as BMW Guggenheim Lab both inside and outside its museums from 2011 to 2014. To this list one might add projects such as Martha Rosler’s 1973 “Garage Sale” that was recently restaged at the MoMA in 2012 and clearly intended to signal the museum’s interest in socially engaged art.

[5] From the cover material of the book Global Activism: Art and Conflict in the 21st Century, edited by Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015).

[6] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). p. 223. BAVO’s webpage is: http://www.spatialagency.net/database/why/political/bavo

[7] Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participation Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, (New York: Verso, 2012).

[8] Regarding Abu Dhabi’s high-priced investment in Western museum branding see: Who Builds Your Architecture http://whobuilds.org/ and Gulf Labor Coalition http://gulflabor.org/. On the relationship between art asset funds and ultra-wealth collectors see: Andrea Fraser, “There’s No Place Like Home / L’1% C’est Moi,” a downloadable pdf is available from Continent at: http://www.continentcontinent.cc/index.php/continent/article/view/108

[9] Jared Keller, “Evaluating Iran’s Twitter Revolution,” The Atlantic, June 18, 2010: http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2010/06/evaluating-irans-twitter-revolution/58337/

[10] David Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography (London: AK Press, 2009).

[11] Greg Sholette and Oliver Ressler, “Unspeaking the Grammar of Finance,” introduction to It’s The Political Economy, Stupid: The Global Financial Crisis in Art and Theory (London: Pluto Press, 2013).

[12] The Financialization of Capitalism by John Bellamy Foster, Monthly Review (March 11, 2007): http://monthlyreview.org/2007/04/01/the-financialization-of-capitalism/

[13] Carol Vogel, “Bacon Triptych Auctioned for Record $86 Million,” The New York Times, May 15, 2008: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/15/arts/design/15auction.html. See also Tierney Sneed, “5 Art Auction Record Breakers That Prove the Industry Is Booming: Art history was made at auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s this week,” US News & World Report (Nov. 14, 2013): http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2013/11/14/christies-142-million-francis-bacon-sale-and-this-weeks-other-art-auction-record-breakers

[14] “Fitch Assigns ‘A’ to Lehman Brothers Holdings Capital Trust VII,” Business Wire, May 9, 2007: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20070509006056/en/Fitch-Assigns-Lehman-Brothers-Holdings-Capital-Trust#.VPtOVmTF_1g

[15] Alexandra Peers, “The Fine Art of Surviving the Crash in Auction Prices,” The Wall Street Journal, November 20th, 2008: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB122713503996042291

[16] Chinese capital, which was not affected by the crash, no doubt played a part in this stability, see: Alexander Forbes, “TEFAF Art Market Report Says 2013 Best Year on Record Since 2007, With Market Outlook Bullish,” artnetnews, March 12, 2014: http://news.artnet.com/market/tefaf-art-market-report-says-2013-best-year-on-record-since-2007-with-market-outlook-bullish-5358/

[17] Gilligan’s examples include Richard Prince’s endlessly recycled works, and Seth Price’s reworking videos that bear “a striking similarity to financial derivatives in one particularly suggestive way: they derive their value from the value of something else.” From Melanie Gilligan, “Derrivative Days,” in Greg Sholette and Oliver Ressler, It’s The Political Economy, Stupid, pp. 73-81.

[18] W.A.G.E.: http://www.wageforwork.com/

BFAMFAPHD: http://bfamfaphd.com/

Debtfair: http://www.debtfair.org/

Art & Labor: http://artsandlabor.org/

ArtLeaks: http://art-leaks.org/

Gulf Labor: Coalition http://gulflabor.org/

Artist’s Union: http://www.artistsunionengland.org.uk/

[19] See: The Artist as Debtor: http://artanddebt.org/; the CAA panel http://conference.collegeart.org/programs/public-art-dialogue-student-debt-real-estate-and-the-arts/; Free/Slow University: http://www.britishcouncil.pl/en/events/conference-freeslow-university-warsaw. Also see Erica Ho, “Study: Art School Graduates Rack Up the Most Debt,” Feb. 21, 2013, Time online: http://newsfeed.time.com/2013/02/21/study-art-school-graduates-rack-up-the-most-debt/

[20] Julian Stallabrass, Art Incorporated: The Story of Contemporary Art, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

[21] For a strong argument to this effect see Tom Finkelpearl’s book What We Made: Conversations on Art as Social Cooperation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

[22] Blake Stimson and Greg Sholette, “Periodising Collectivism,” in Third Text, vol. 18, no. 6 (2004), p. 583, revised and reprinted as the introduction to Collectivism After Modernism: The Art of Social Imagination after the War, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

[23] Stephen Wright, Toward a Lexicon of Usership, Op. cit.

[24] Grant Kester, “Aesthetic Evangelists: The Rhetoric of Empowerment and Conversion in Contemporary Community Art,” Afterimage, vol.22, no.6 (January, 1995), pp.5-11.

[25] See Ben Davis, “A critique of social practice art: What does it mean to be a political artist?” International Socialist Review, no. 90 (July 2013): http://isreview.org/issue/90/critique-social-practice-art. Naturally socially engaged art still has many critics, especially amongst more orthodox critics, but following the substantial research of historians such as Grant Kester and Clair Bishop even its doubters are obliged to treat this work seriously as art, a courtesy that was not extended to community-based art in the recent past.

[26] “Is Social Practice Gentrifying Community Arts?,” a conversation between Rick Lowe and Nato Thompson at the Creative Time Summit, October 2013, a transcript is available from Bad At Sports here: http://badatsports.com/2013/is-social-practice-gentrifying-community-arts/

[27] Chris Kraus, “Ambiguous Virtues of Art School,” Artspace (March 2, 2015), http://www.artspace.com/magazine/news_events/chris-kraus-akademie-x

[28] Fredric Jameson, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), pp. 80-81.

[29] Stephen Wright, Usership. Op. cit., p. 4.

[30] “It is my contention that some socially engaged artworks can be distinguished from others by the degree to which they provoke reflection on the contingent systems that support the management of life. An interest in such acts of support coincides with the project of performance,” Shannon Jackson, Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics (New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 29. Wright would likely respond that his idea of usership-driven art is work that is not performed as art, but literally and redundantly is action in the “real-world,” quite unlike performative practices whose content is, first and foremost, art, and then only secondarily perhaps an action, useful or otherwise, in the real world. See Wright, Usership, p.16.

[31] An obviously intriguing problem is how one might approach art that is detached from its artistic framing in critical, aesthetic terms. That, however, will require another essay in itself.

[32] Martin Pengelly, “Pittsburgh restaurant receives death threats in ‘anti-Israel messages’ furor,” The Guardian, Nov. 9, 2014: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/09/pittsburgh-restaurant-conflict-kitchen-death-threats-israel

[33] Theaster Gates TED Talk, “How to revive a neighborhood: with imagination, beauty and art”. Published March 26, 2015: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9ry1M7JlyE

[34] Consider for example Nike’s elegantly designed fashion accessory Fuelband 3.0: an integrated cybernetic device in which the company monitors the muscular movements of the bracelet’s wearer in real time via Blutooth. While Nike sends information about the customer’s physical fitness, it also aggregates human data useful for developing future products that the company will market to these same individuals. It is not hard to imagine a social practice type project that would operate in a similar way substituting, say, the Guggenheim or Museum of Modern Art for Nike.

[35] Brian Holmes, “Future Map, 2007,” http://roundtable.kein.org/node/1332

[36] Quoted in an email to me from Monday, March 23, 2015 at 10:04 AM.

[37] Ricardo Dominquez and Electronic Disturbance Theater designed a pro-Zapatista virtual sit-in platform aimed at overloading and crashing the Mexican Government’s website. This is a form of “hacktavism” still in use by the group Anonymous today.

[38] David Garcia and Geert Lovink, “The ABC of Tactical Media,” from Nettime.org (May 16, 1997): http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9705/msg00096.html

[39] A discussion of EDT’s floodnet is found here: http://museumarteutil.net/projects/zapatista-tactical-floodnet/

[40] The situation escalated when Dominquez organized a virtual sit-in of the UC President’s website: http://www.utsandiego.com/news/2010/apr/06/activist-ucsd-professor-facing-unusual-scrutiny/

[41] Viktor Shklovsky, Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot (Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2007); Fisher op cit.

[42] Nato Thompson, “Trespassing Toward Relevance,” from Thompson and Sholette, The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), p 17. The book that came out of the exhibition which Thompson, myself and MASS MoCA designer Arjen Noordeman produced, went on to be reprinted several times and used in numerous classroom curricula. It is not the topic of this paper however.

[43] The Interventionists, p 60.

[44] Choire Sicha, “The Guide,” December 12, 2005, The New York Times. The only lengthier critical responses were by Carlos Basualdo, and T.J.Demos in Artforum, though these reviews largely recycled existing critical paradigms about site-specific art without successfully engaging in the concept of tactical media in relation to the counter-globalization movement or “the social turn” in art. http://www.mutualart.com/OpenArticle/-THE-INTERVENTIONISTS–ART-IN-THE-SOCIAL/9FE37A35791E22C3

[45] See: Department of Space & Land Reclamation website: http://www.counterproductiveindustries.com/dslr/

[46] Henry Moss, “The Climb to Oatman’s Crash Site: Mass MoCA’s Discontinued Boiler Plant,” Interventions/Adaptive Reuse, vol. 2 (2011), p 6.

[47] “Another Art World is Possible,” happens to be the title of an essay by theorist Gene Ray from the same years as The Interventionists exhibition in Third Text, vol. 18, no. 6, (2004), pp. 565-572.

[48] For example the Artists as House Guest program at the Museum of Modern Art in New York which is mentioned in Randy Kennedy’s article, “Outside the Citidal, Social Practice Art Is Intended to Nurture,” The New York Times, March 20, 3013: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/arts/design/outside-the-citadel-social-practice-art-is-intended-to-nurture.html?pagewanted=2&_r=2, and also “The politics of the social in contemporary art,” at the Tate Modern Starr Auditorium, February 15, 2013: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/conference/politics-social-contemporary-art

[49] Fuzzy Biological Sabotage on CAE website: http://www.critical-art.net/MolecularInvasion.html

[50] To read more about the investigation see the Critical Art Ensemble Defense Fund: http://www.caedefensefund.org/

[51] The CAE Defense Fund, which at the time of the “Interventionists” opening had already been established by artists Claire Pentacost and Gregg Bordowitz, along with Jacques Servin and Igor Vamos of The Yes Men, emerged from the emergency meeting with a constituency of supporters ready to go to work raising legal funds and publicizing the senseless injustice of the accusations against Kurtz. While the overall outlook of the Defense Fund’s members continued to argue in their lectures and writings in favor of amateur scientific research and the right to engage in political disobedience via forms of tactical media, Kurtz’s actual legal case pivoted on the artist’s First Amendment guarantee of free speech. Caught up in the need to defend a fellow politically active artist from what appeared to be government railroading I endorsed this “free speech” defense with its more pragmatic view. Ultimately, however, the government’s prosecutorial position was defeated by its own flawed logic, though not after many thousands of dollars was raised. (Thanks to Lucia Sommer for this correction to my previous note in an email dated Monday, Sep 7, 2015 at 5:34 PM)

[52] This is certainly seems to be the position of artist Rubén Ortiz Torres who was an artist Thompson exhibited in The Interventionsts. Torres believes that the occasion of the 2004 show was “supposed to be the moment when the art world (or at least part of it) would recognize the practices that a lot of artists (if not most) do in art schools and, alternative spaces and other circuits outside commercial galleries and museums. However it seemed that the Steve Kurtz incident cancelled or was used to cancel that opportunity.” Notably he adds “I see “social practice” as a very ineffective way to do politics trying to validate them and justify them as art. It seems a way more bureaucratic, moralistic, self righteous and pretentious notion than the more open, anarchist and situationist one of “Interventionism.” Cited in an email to me from Monday, October 14, 2013 at 8:45 PM.

[53] Blake Stimson, “The Form of the Informal,” Journal of Contemporary African Art, no. 34 (Spring 2014), p. 36.

[54] “The thing changes not one bit, yet once the trapdoor springs open and the ‘dark agents’ are on the loose, nothing could be more different.” The dark agency is for Wright the allure of the thing that is both a proposition about art, and a completely redundant activity, object, practice of everyday life. Usership, p 7.

[55] John Roberts, “The Political Economization of Art,” in It’s The Political Economy, Stupid, edited by Greg Sholette and Oliver Ressler (London: Pluto Press, 2013), pp. 63-71.

[56] Jan Rehmann, Theories of Ideology: The Powers of Alienation and Subjection, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014), p. 12.

[57] Tactical Urbanism/The Street Plans Collaborative: http://issuu.com/streetplanscollaborative

[58] A Painting for a Family Dinner, 2012, Alina and Jeff Bliumis: gerempty.org/nc/home/what-we-do/artists/artist/bliumis-alina-and-jeff/

[59] No Longer Empty, Art in Empty Spaces: http://www.nolongerempty.org/nc/home/events/event/program-art-in-empty-spaces-with-community-board/

[60] Examples of gift art are drawn from the Ted Purves book, What We Want is Free (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2004).

[61] For a discussion regarding the Marxist concept of sublation in relation to art see a string of responses to my paper “Let’s Talk About the Debt Due” available at The Artist As Debtor website: http://artanddebt.org/greg-sholette-lets-talk-about-the-debt-due-for/ with the feedback located here: http://artanddebt.org/lets-talk-about-the-debt-do-for-responses/

Futher Reading

Erika Biddle, “Re-Animating Joseph Beuys’ ‘Social Sculpture’”: Artistic Interventions and the Occupy Movement,” in Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 11, no. 1 (2014). Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5532769/Re-Animating_Joseph_Beuys_Social_Sculpture_Artistic_Interventions_and_the_Occupy_Movement

Brian Holmes, Unleashing the Collective Phantoms: Essays in Reverse Imagineering, (New York: Autonomedia Press, 2008).