Antinomies of Art Activism and Documentation: The Curatorial Approach of Agitprop at the Brooklyn Museum

Izabel Galliera

The globally ambitious exhibition Agitprop (December 2015–August 2016), at the Brooklyn Museum has literally grown over its eight-month lifespan. The exhibition brings together artists, activists and collectives from around the world, including SAHMAT (Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust) from India, Ganzeer from Egypt, Chto Delat? from Russia, Jelili Atiku from Nigeria, Zhang Dali, Huang Rui and Song Dong from China along with a number of American practitioners, such as Martha Rosler, The Yes Men, Guerilla Girls, Friends of William Blake and Occupy Museums. The numerous projects address various social and political themes, such as antiwar demonstration, AIDS activism, environmental policy, the effects of mass incarceration and economic inequality. The key question that one feels compelled to ask in relation to Agitprop is whether museum exhibitions can provide a valid platform for furthering the activist causes underlying socially and politically-committed art practices or whether the risk of institutionalizing and aestheticizing forms of art activism is, practically speaking, too high for such practices to maintain their critical edge while being encapsulated within official institutional frameworks.

[Image 1-Brooklyn Museum, photograph courtesy of the author]

[Image 2-Installation view of Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

The material on display encompasses various media, such as photographs, charts, videos, posters, pamphlets, sculptures, and interactive electronic devices that collectively, demand a slowed-down viewing experience. Also, through its sheer number of videos and text-heavy works, Agitprop invites multiple return visits. The exhibition is presented in three galleries, which are connected like arteries to a beating heart, to a central triangular-shaped gallery housing the permanent installation of Dinner Party (1974-1979) by Judy Chicago, which entered the museum collection in 2002. This art historically significant second-wave feminist artwork provides Agitprop with its spatial, historical and conceptual core.

[Image 3-Partial views of Judy Chicago, Dinner Party, 1974—1979, (left side) and Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, right side), Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

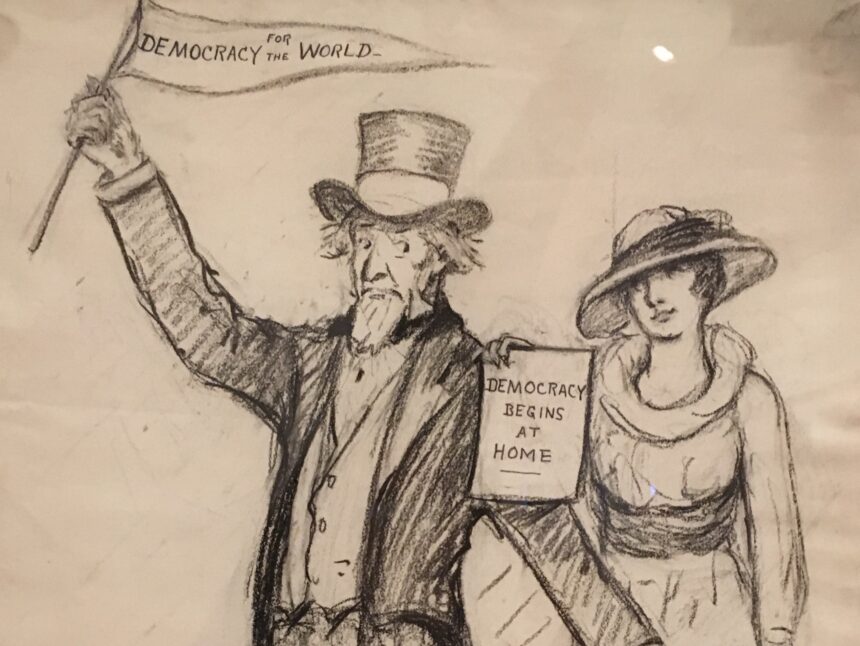

As one might expect from an exhibition in the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth Sackler Feminist Center, a feminist theme guided the curatorial team’s initial selection of works, including the historical case studies. Two prominent displays at the opposite ends of the main gallery offer a look back at early twentieth-century struggles for social justice fought simultaneously on two continents. As a multi-media installation, Soviet Women and Agitprop includes posters from 1931 by Valentina Kulagina representing Soviet women workers. It also features two videos, one from 1929 titled Misery and Fortune of Woman created as an appeal for safe and legal abortion across Europe, following the Soviet government’s legalization of abortion in 1920. At the other end of the gallery is the Women’s Suffrage in the United States display, which includes cartoons, posters, magazine covers and documentary photographs of American women fighting for their right to vote, which was only granted in 1920 with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment.

[Image 4-Installation view of Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

[Image 5-Nina Allender (American, 1872–1956), If I could only keep my left hand from knowing what my right hand is doing, (1917), charcoal, graphite, and ink on paper. Displayed in the Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

Aiming for an experimental approach to exhibition making, Agitprop’s curatorial team identified artists based on a three-part selection process. The first wave of Agitprop opened on December 11, 2015, with works by twenty artists selected by the Center’s staff. The second wave debuted on February 17, 2016 with the display of works by artists nominated by the first-wave artists, and a third and final wave began on April 6, 2016, with artists invited by second-wave participants. The exhibition’s curatorial approach engages broadly with well-known curatorial models such as the ‘artist as curator’ format and the ‘curators as artists’ model. The first model, with roots in the 1960s and 1970s conceptual and institutional critique movements, has been popularized in the 1990s with artists such as Liam Gillick, Walid Raad and Rirkrit Tiravanija working with relational aesthetic and installation art. Harald Szeemann inaugurated the ‘curators as artists’ model in his seminal exhibitions such as Live in Your Head (When Attitudes Become Form: Works-Process-Concept-Situations-Information) (1969). According to art historian Terry Smith:

The curator-as-artist approach meant foregrounding one’s vision in the publicity for the show and in its presentation in the gallery, thus making the curator’s thinking a conscious factor in the visitor’s experience. It also meant that exhibitions came to be understood as works-in-progress, subject to change by the artists involved (many works transformed over time, others changed via visitor participation, thus the whole ensemble could be in constant motion) and by the curator’s evolving conception of what he or she wanted to convey. [1]

On one hand, Agitprop aims to replace the singular voice and vision of the curator solely responsible for selecting works with a horizontal and collectively-authored curatorial approach by inviting artists to nominate works by other artists for the exhibition. The exhibition’s structure allows its component parts to grow and alter through time, stimulating the visualization of not only already present networks among artists, but also new connections forged within and through the exhibition. Agitprop’s curatorial wall text reads: “In this way, the final installation will reflect multiple political and artistic positions, determined by the artists rather than by the institution, while exploring how networks of artists, collectives, and activists sustain and amplify these activities.”

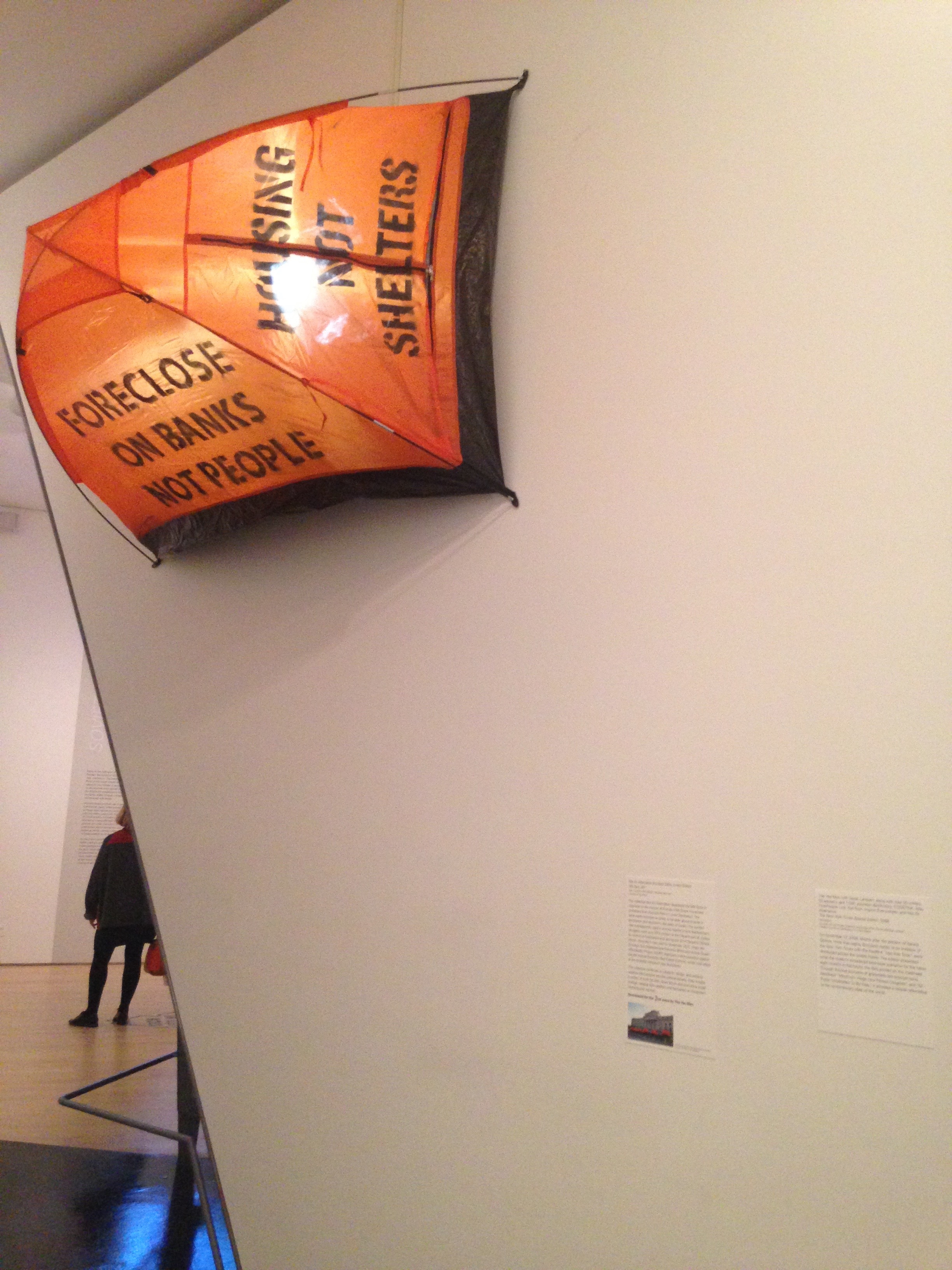

On the other hand, by conceptualizing and setting up this overall framework, the exhibition firmly asserts the central role played by the authority of the curators. As such, the nomination of artists by fellow artists functions as means of generating content within an already pre-established structure. Moreover, while it may appear to open up the exhibition to a wide rage of artists who otherwise might not be invited to be part of the show, the exhibition’s three-wave format conveys an uneasy hierarchy. It may also be seen as a catalyst for the rapid historicization of these practices. The first round of well-known and institutionalized contemporary artists like Guerilla Girls, Martha Rosler and The Yes Men nominate lesser known and art historically less influential artists in the second and third waves. For instance, The Yes Men nominated the collective Not an Alternative. The latter exhibited Mili-Tent, an orange tent with spray painted slogans and flashlight. This object was part of a series of tents mounted on poles, conceived in response to the eviction of Occupy Wall Street movement protesters from Zuccotti Park in 2011. In turn, Not An Alternative nominated the art, design and activist collective Enmedio from Spain, who exhibited a two-minute video Fiesta Cierra Bankia, which documents the artist group’s 2012 impromptu party inside a bank. Using balloons, confetti, noisemakers, and a disco ball they surprised and celebrated an unsuspecting customer who closed her bank account. They were thus attempting to respond to the Spanish government’s decision to bail out the bankrupt Bankia banking system.

[Image 6-Installation view of Not An Alternative (founded 2004, United States). Mili-Tent, 2011, Tent, Coroplast, LED flashlight, stenciled spray paint. Displayed in Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

A problematic tension arises from contextualizing contemporary art activists from around the globe within a genealogy of historical social movements rooted primarily in the United States: the women’s suffrage movement, the NAACP’s Anti-Lynching Campaign and The Federal Theater Project, a branch of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration. As social and political struggles for human rights are certainly not limited to the American context, it is curious that United States democratic framework emerges as the norm and main reference point in an exhibition that is at least ostensibly globally oriented. One is left to wonder about the locally and geopolitically specific historical genealogies of contemporary practitioners, in for instance, Nigeria, India and China.

Agitprop also embodies the ‘exhibition as document’ model, and, as such, its contents comprise of documentation and records of time-specific works made in different contexts.[2] The exhibition as document model is rooted in the practice of the 1960s and 1970s conceptualist artists and curators such as Seth Siegelaub and Lucy R. Lippard, who challenged the boundaries between the roles of critic, curator and artist. In fact, in 2012 the Brooklyn Museum staged an exhibition as document, displaying content featured in Lippard’s 1973 book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. The latter was “an annotated chronology of events, exhibitions, projects, writings, and ideas both realized and imagined […].”[3] In an ironic reversal and a clear indication of the institutionalization of Lippard’s work, the 1973 conceptual exhibition in a book/catalogue only format, conceived to bypass the physical space of the gallery, was transformed in 2012 into a traditional museum exhibition. Agitprop situates itself within this history and it actually includes one of the works featured in Lippard’s Six Years: a display case with records of Luis Camnitzer’s First Class Mail Exhibition # 1, one of three conceptual exhibitions distributed by mail in 1967.

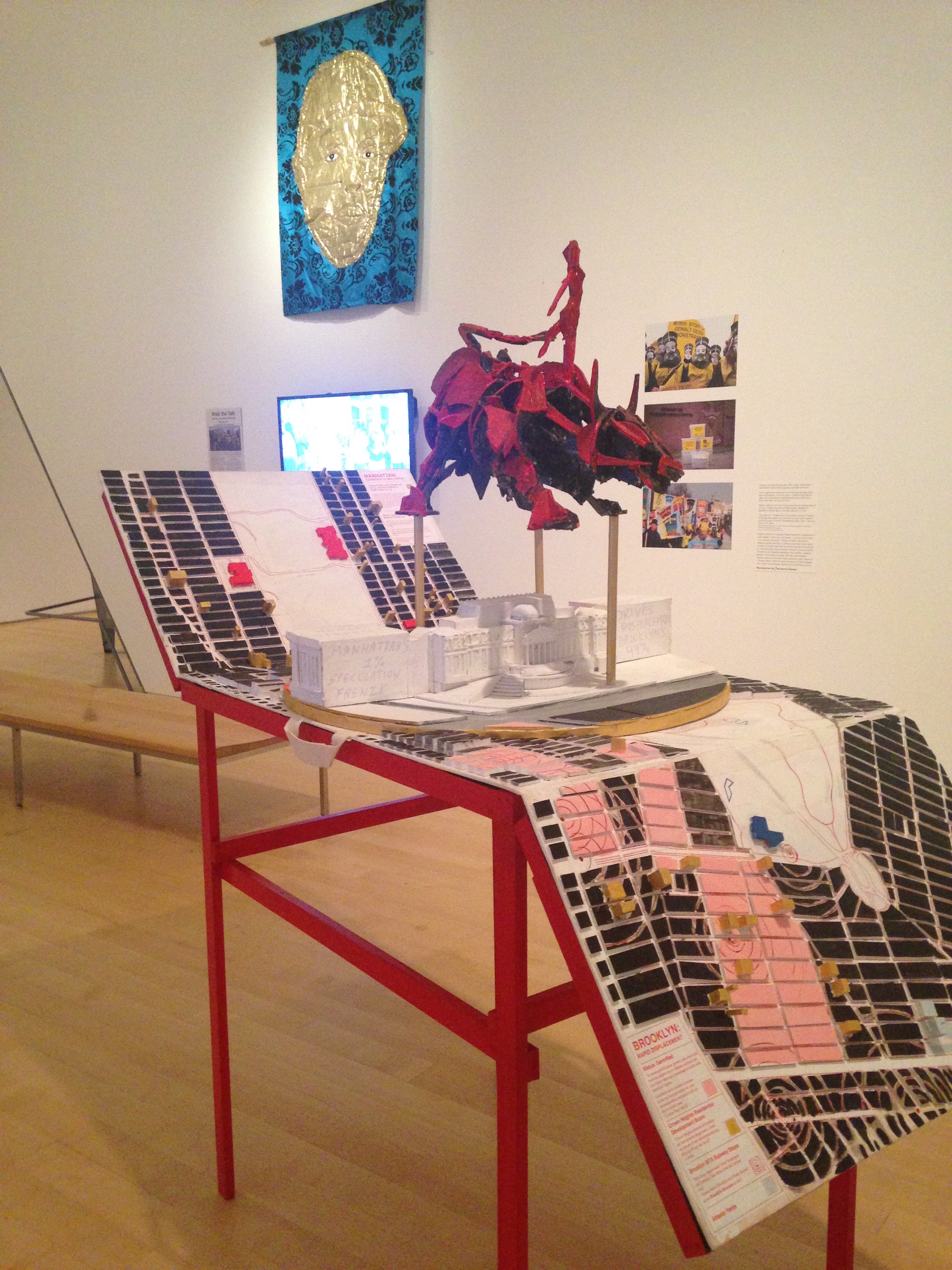

It is its documentary nature that reveals Agitprop’s most productive antinomies. At first glance, the exhibition appears to navigate the contentious boundary between art activism and art documentation with difficulty, interrogating, as it may, how is one to present process-based work in a gallery context. For example, are we to view Eroding Plazas and Accumulating Resistance (2016) by Occupy Museums as an art sculpture, useful object used to strategize for a protest action, a post-event art documentation or some combination of all these? If we understand the work on display as records of specific actions, it is an undeniable fact that documentary material of all kinds represents the only means by which the time and space-specific actions and practices of contemporary practitioners can be made known to a wider public. On the other hand, several works in the exhibition function clearly as art, design and art activism. For example, the take-away works, such as the Play Smart (2016) trading cards and safer sex kits with seductive images and slogans to promote HIV awareness, and the foldout pamphlet The People’s Plate Pamphlet #1 (2015) that addresses issues of food justice within urban communities of color, invite visitors to aid in the promotion of these causes beyond the spaces of the museum.

[Image 7-Installation view of Occupy Museums (founded 2011, United States). Core group members: Tal Beery (American, born 1984), Imani Brown (American, born 1988), Noah Fischer (American, born 1977), and a member who must remain anonymous, Eroding Plazas and Accumulating Resistance (2016), Mixed Media. In Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

As a documentation exhibition, Agitprop both aestheticizes politics and politicizes aesthetics, at once forestalling and enabling the resurrection of its exhibited causes. In their curatorial statement, the curators interchangeably use terms such as “activist art practices,” “contemporary artists,” and “creative activism,” clearly conflating art and activism. Such a fusion echoes Boris Groys’s recent commentary on the contradictory yet productive nature of contemporary art activism, which instead of bypassing art it aims to make art useful in its activist causes.[4] Such antinomies of art activism and documentation collide in A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing (2016), an installation not part of the three-wave structure yet collaboratively conceived by a number of artists and activists in the exhibition: Alexander Dwinell, Noah Fischer, The Illuminator, Movement to Protect the People, Not An Alternative, Sarah Quinter, Antonio Serna, Arts & Labor’s Alternative Economies Working Group, Ultra-Red and Betty Yu.

Acting as a community notification board, A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing aimed at opening discussion on the gentrification and displacement threatening the Flatbush and Crown Heights neighborhoods. According to the museum label, the “project was initiated as a result of conversations between the makers and the Brooklyn Museum after the 6th Annual Brooklyn Real Estate Summit was held at the Museum in November, 2015.” A number of activists and local community organizations, including Not An Alternative and Movement to Protect the People staged protests in front of the museum in November 2015, just a few weeks before the opening of Agitprop in December 2015. The inclusion of the installation in the exhibition reflects the Museum’s desire to engage in a self-reflexive process about its role and responsibility within and to the local communities that they serve. As such, the installation includes a petition addressed to “All Our Elected Officials!–Do Not Rezone Community Board 9!” It invites people to sign the petition to make their voices heard. Are we to assume that residents from the threatened nearby neighborhoods will actually visit the exhibition to sign the petition? However transparent and empowering in its intention, the installation ultimately remains a symbolic gesture, a document to be archived and absorbed by the institution. A handwritten note on the petition by an anonymous viewer reads: “WTF. Sign This!!! So many white people are just walking away, turning around . . . ”

[Image 8-Detail of the installation A People’s Monument to Anti-Displacement Organizing, 2016, mixed media created by Alexander Dwinell, Noah Fischer, The Illuminator, Movement to Protect the People, Not An Alternative, Sarah Quinter, Antonio Serna, Arts & Labor’s Alternative Economies Working Group, Ultra-Red and Betty Yu. Displayed in Agitprop exhibition, December 2015–August 2016, Brooklyn Museum. Photograph courtesy of the author]

[1] Terry Smith, Thinking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curators International, 2012), p. 132.

[2]A recent and well-known curatorial example is the 2013 exhibition When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013 curated by Germano Celant, which consisted in re-creating Szeemann’s exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1969. While Agitprop is not a re-creation of a single exhibition, it certainly includes a number of displays that attempt to both recreate and document time-specific actions. See “Re-Curating Attitudes, Bern 1969/Venice 2013, Germano Cela in conversation with Terry Smith, in Talking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curators International, 2015), pp. 248 – 277.

[3] Catherine Morris and Vincent Bonin, “An introduction to Six Years,” in Materializing Six Years: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art, edited by Catherine Morris and Vincent Bonin (Cambridge Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2012), p. xv.

[4] Boris Groys, “On Art Activism,” e-flux journal, 56, (June 2014), accessed April 23, 2016, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/on-art-activism/

Izabel Galliera teaches in the Department of Art and Art History at McDaniel College in Maryland, where she recently curated the exhibition Alternative Cartographies: Artists Claiming Public Space (November – December 2015). Her article “Self-Institutionalizing as Political Agency: Contemporary Art Practice in Bucharest and Budapest” had just appeared in the MIT Press Journal ArtMargins in the June 2016 issue. Izabel’s book Socially Engaged Art after 1989: Art and Civil Society in Central and Eastern Europe is forthcoming early 2017 (I.B. Tauris).