Organization, Engagement, Coloniality—Hangar: Centro de Investigação Artística in Lisbon

Carlos Garrido Castellano

This paper analyzes the work of Hangar: Centro de Investigação Artística, the first artist-managed space in Portugal dealing with postcolonial issues and African art. Through an analysis of Hangar´s activities, I aim to critically examine how African art has been displayed and consumed in Portugal, particularly in relation to the production of the country´s contradictory postcolonial image. The emergence of Hangar and the development of long-term relations both with emerging artists born in Africa and with the local Afro-Portuguese community imply, I suggest, a new and more fruitful approach. This collaboration also provides new tools for artists and cultural agents to strengthen their agency against the forces of touristification and commoditization that Lisbon and contemporary art from Portuguese-speaking African countries are respectively experiencing. The text is followed by a short interview with Hangar´ founders and directors Bruno Leitão and Mónica de Miranda.

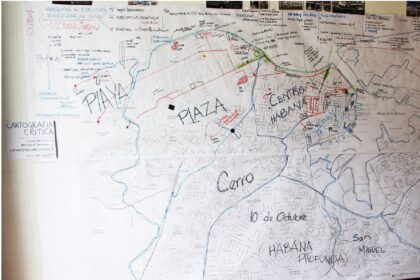

Portugal became a common venue for African artists within the last decades of the 20th Century, especially for those coming from the PALOP countries (Países Africanos de Língua Portuguesa, or Portuguese-speaking African counties). Echoing the interest of biennials and major art centers, the national art institutions—especially those located in Lisbon—organized or hosted several large-scale exhibitions, including major curatorial projects and solo exhibitions of a wide variety of well-known and up-to-coming artists from the continent.[1] A special and widely problematic focus on the former colonial territories of Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Mozambique, and São Tomé & Príncipe presided over that process. The presence of African art within the Portuguese cultural and exhibitional landscape is connected with the process of redefinition of Portuguese postcolonial identity. In some way, then, the increasing number of cultural and artistic events related to Africa arises as a response to the predicament of the Portuguese present, marked by integration into the European Union, the country´s modernization, and the configuration of a multicultural and multiracial citizenry. Those projects, of course, are not exempt from contradictions: one the one hand, there is a growing interest in approaching critically the cultural predicament of engaging with Portugal´s postcolonial geopolitics (see Castelo 1998; Bastos et al. 2002; Vale de Almeida 2000, 2006; Ribeiro Sanches 2006; Ribeiro Sanches et al. 2011; Sousa Santos 1993, 2002); on the other, at the same time, the cultural manifestations produced within the African continent and those linked to African migration into Portugal have been commoditized and spectacularized, transforming Lisbon into a major cultural center of the “Lusophone” Atlantic.

When confronting the project that I briefly summarized above, one important consideration is the disparity between the display and the criticism of artistic manifestations, a phenomenon that is increasingly changing, particularly due to the labor of young researchers. The number of resources dealing with Lusophone African art is growing at the same time that some artists and locations have received more and more critical attention.[2] In addition, the exhibitions focusing on African art have largely misrepresented and ignored Afro-descendant populations, creating a gap between “modern” artworks and visual discourses oriented toward international consumption and dissemination, and the local reality and cultural manifestations of migrant populations. Related to that, the loci of African cultural and curatorial practices arise as points of intersection and contrast between national expectations, postcolonial anxieties, and transnational fluxes, in which audiences and territorial demarcations are very much crisscrossing class and cultural differences.

Hangar focuses on postcolonial and diasporic issues concerning several regions of the world. However, the center has paid special attention to African artists. The engagement of Hangar with Africa is handled through two main initiatives: the center´s programming and the establishment of partnerships with already existing or emerging independent, artist-managed spaces on the continent. In terms of programming, Hangar has pioneered a comprehensive, non-exhibition-based approach to African creativity, encouraging long-term collaborations and in-depth research. Many of the activities involving African artists possess a lower profile than the large-scale, collective shows that can be found in museums and biennials. For example, long-term research residencies, interaction with several “local” communities, and critical conversations and exchanges with curators, fellow-artists, and thinkers have all been undertaken. Irineu Destourelles from Cape Verde, René Tavares from São Tomé, Edson Chagas from Angola, and Eurídice Kala and Mário Macilau from Mozambique are among the Lusophone artists who developed residencies in Hangar, employing that time not only for the preparation of exhibitions and the production of work, but also for engaging with Lisbon´s history and present, and for interacting with the dwellers and visitors of Graça. This does not always happen, however, being dependent on the artist´s interest and the kind of research activity she intends to develop.

![[Image 2: Talk by Kiluanki Kia Henda]](http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Image-5-1024x683.jpg)

In the following conversation I intended to discuss with the founders of Hangar some of the issues outlined in the previous text, paying special attention to the center´s interest in Lusophone African art. The reason for juxtaposing the previous insights with this group conversation has to do with my own relationship with Hangar. Since its creation I have collaborated regularly with Hangar, giving talks, participating in seminars and roundtables, and also attending performances and concerts. Through this group interview, my interest is to analyze how Hangar´s founders see their position regarding the context of Lisbon and regarding a broader transnational Lusophone framework.

Carlos Garrido: What are the reasons behind the creation of Hangar? Which needs do you intend to fulfill?

Bruno Leitão: Hangar arose in response to different issues, but above all because of the need to have artists, curators, and researchers sitting at the same table. This is our foundation, running through all of Hangar´s activities. Researchers work in a particular way. Curators too, they have specific criteria on many issues, such as the selection of artists, and artists have their own interests in play. We wanted to put those three spheres together. Furthermore, we had an interest in transcending the North-South divide, in establishing South-South links. The territorial scope of Hangar is far-reaching, but we put a big emphasis on Latin America and Africa, focusing mostly—but not exclusively—on the visual arts. This is our primary area of interest. As a response to those concerns, we configure a schedule having to do with American and African artists, but also with their diasporas, all without forgetting a strong link to recent Portuguese art. We have a program called “Portuguese art since 1974,” and we want to map our contemporary history, to approach people who are still there to be contacted, alive and active, including curators, critics, and gallerists.

Mónica de Miranda: Hangar was created from a cultural association, Xerem, which was founded in 2010. Xerem started developing artistic residencies and cultural exchanges within the Triangle Network. Those exchanges were sporadic, although they grew in the last few years, when we started establishing partnerships with Africa and Brazil. This created a more intense and active panorama, and thus the need of finding a space for the schedule to be permanent. Then we applied to a call for local development in the areas of art and culture, we got it, and from there we created Hangar. It became a structure larger than the association behind it; it acquired its own shape, with a new team of people focusing on specific tasks. We have a horizontal structure where each of us coordinates a part and is responsible for each of the activities, but then we share our points of view about all the initiatives we develop. Our project inherits the tradition and experience of artist-run spaces, although we are not only artists managing the center, since we try to foster a more horizontal and less hierarchic dialogue with curators and with theory. We believe that artists can contribute to a more attentive and deeper thought and critique, we encourage collaboration, and we partake in Hangar´s four main areas, which are research, exhibitions, residencies, and participation. Those four areas are interrelated in many ways—for instance, a workshop can turn into an exhibition, an exhibition can end up being a conference series or a research process, this could develop into an exhibition, and so on.

![[Image 3: View of Martim Moniz Square]](http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Image-7-1024x576.jpg)

B: As you know, I have a connection with Madrid, but for me the good thing about Hangar being here in Lisbon is that here there is a natural link with Africa, one that you won´t find in Madrid, for example. In turn, Madrid is strongly connected with Latin America, something that doesn´t happen in Lisbon. For me it is like having the best of both worlds. Mónica has more contacts with and knowledge in relation to Africa; I am more oriented to Latin America and North Europe, but above all to Spain and Latin America. This is one of our biggest advantages.

The fact of being in Graça… It´s a quarter that was not trendy when we arrived. At first we were a bit indifferent about the location, although Graça is interesting because we are close to Martim Moniz, to Intendente, and we have several communities around here coming from countries we seek to engage with. Now we develop work that seeks to exchange feedback with our community, to create a kind of interface with the people living around us. The results of our actions for the Bangladeshi, Indian, or African diasporic communities inhabiting those areas of Lisbon… I´m not a sociologist, you see, so I cannot talk much about that. Only when we’ve had several years of activity will we see if the balance is positive or what kind of impact are we having, but I know for sure that there is an impact on our practice. We’ve tried to encourage the encounter, for example, when we organize potlucks with the Angolan community, we intend to attract persons that have nothing to do with the art world. We try to attract our neighbors to Hangar in order to create that interface.

M: Graça was a happy accident. The place found us. We were searching for a place, and the building we found with the characteristics we wanted was in that neighborhood. Soon the location became important for the project, as it is an area with a large number of migrant communities but also one with a very settled Portuguese population interacting in the same place. We are on a hill, so we can overlook Lisbon, but we are still away from the touristification that is taking place downtown. The neighborhood is still very traditional but also has a cosmopolitan feel starting to occur with many associations and artists moving into this part of town. In our project, we intended to work with different audiences and open the experience of contemporary art not only to the usual suspects but to a more diversified public. We wanted art to interact with everyday life, so that is why we also have a public program including music events that aim to reach out into the community. I lived in London for fifteen years, and this dynamic of artist-run spaces interacting with their geographical locations is natural for me. In some sense, my London background taught me that approach; I was involved in London with many art projects that occurred in inner city neighborhoods like Brixton and Peckham. In some ways, I exported that experience with me, to this project.

![[Image 4: Participatory Workshop in a local arts high school with artist Faisal Abdul Allah]](http://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Image-10-1024x683.jpg)

B: It´s curious; we do not work uniquely with postcolonial issues, although this is one of our main lines. I think you are talking about an issue that here in Portugal is yet to be addressed. There is not much criticism about the matter. I think that it is just recently that many things are being developed, even [the newspaper] O Público did a special series on Portugal´s former colonies and so on. I think this is an issue that interests people, but about which you could not talk easily, either due to shame or family ties, something that most of the time provoked situations of shame or hidden pride in many people. When we started organizing activities around those issues, we found a huge audience without making any significant effort. Every time we organize activities not exclusively addressing artistic communities, we find a lot of participation, and I think this is also because of what I said, because those questions were ready to be discussed here in Lisbon. People are willing to talk about these matters, and the good thing about being in Graça is that we do not need to look for the communities of migrants or for the postcolonial reality of the country, they were already here waiting for us. Something happens to me here that I never experienced before in Portugal or in Lisbon: being at an opening and not knowing many of the people that are there. In Lisbon the art world is quite small; when I worked in MauMaus or in the Museu Berardo I knew everybody hanging out at the openings. Here there are many people that are new to me. I think we arrived at the right moment to deal with these issues.

M: Our aim is to open up the experience of contemporary art to people in general and not only to the art crowd. Postcolonial issues in Portugal are still being dealt with through a modernist approach—very few artists are actually from a postcolonial African or diasporic background. Artists are sometimes ghettoized according to the language they speak. Elsewhere, there is currently a large number of African diasporic artists dealing with issues derived from their own experiences. But when you go to a biennale such as Dakar or to events such as the Bamako encounters, Lusophone artists are still a minority. There are only a few Portuguese artists from an African background practicing nowadays in Portugal. Nevertheless, there is a great tendency among Portuguese artists to deal with postcolonial issues. Hangar wants to interact with this predicament. We have created programs such as 180º to aim and encourage young artists from Lusophone contexts, especially African women artists, to develop their projects with curatorial and production support. We also have worked with potential artists from the local community.

![[Image 5: Artist in residency Irineu Destourelles. Open day session.]](https://field-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Image-6.jpg)

B: We have a continuous link with Africa, one not limited to organizing exhibitions. Moreover, we are making a great effort not to focus exclusively on Lusophone Africa. The exhibition we have now [Kin] was curated by Eva Langret, and there are no Lusophone artists in the show. We are trying to open the scope to the whole of Africa, not just to “Portuguese Africa.” That happened as well with a previous exhibition curated by Paul Goodwin, which featured artists such as the Otolith Group, John Akomfrah, and Alia Syed. This is something new here in Portugal—normally you will have either very well-known names or artists native to the former colonies. We have tried to diversify the discussion about Africa.

M: In my case, there is a personal, biographical interest in Africa, one that I also develop in my artistic work. To this, I usually add my extensive experience with the African diaspora in London, creating links that are now being developed in Hangar through partnerships. The collaborations with Paul Goodwin and Eva Langret, with whom I worked in London, came about that way. They are managing two projects that are highly relevant in postcolonial art—the Tiwani Contemporary gallery and Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN), respectively, both in London. This partnership gave rise to major exhibitions at Hangar (Ghosts and Kin), which brought many other regions of Africa and their diasporas to Lisbon. There were artists from South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya participating, but also names such as John Akomfrah and the Otolith Group, who are central in the African diaspora art scene. Some of these artists, especially those taking part in the Kin exhibition, were showing in Portugal for the first time. Some of them are not so well-known here, although their international recognition is huge. So we are contributing to building new bridges, through a discourse that is located in Lisbon but communicates with the outside world.

C: What kind of approaches to the art of the PALOP countries have been developed in Portugal? What are the predominant discourses?

B: There is a high degree of paternalism still in play. There is a high degree of incapacity in perceiving the specificities of each context, what each culture has of its own. There are still not so many exhibitions about Africa or those involving African artists or artists from the African diaspora, although it is a growing phenomenon. That has to do, of course, with the increasing marketability of the issue, but I think this entire process is somehow starting anew. It is not that there are no precedents but… There have been, for example, entire exhibitions prepared for other countries and imported without any critical reflection.

M: There is still a lot to be done. The real input needs to come from the artists themselves and a growing market and context that knows and understands the meaning of “Lusophone African art.” It is not only an exotic product to be consumed in art fairs or part of the political agenda of councils to study migration through the arts; it is a cultural manifestation with its own discourses. But for that to happen, the artists must be responsible for leading the movement and must refuse to be puppets in the hands of institutions or outmoded modernist and colonialist approaches from art critics, curators, and museums.

M: From the beginning, we have tried to involve the African communities living in Lisbon. The question of the African diasporas in Portugal is a tricky one. First, there are few artists of African origin born here, very few, you can count us with the fingers of one hand. Then you have Portuguese artists dealing with postcolonial issues. There is also a community of artists who are Portuguese citizens, they live here, but they were born in Africa, therefore they will not fit the category of African diaspora although they have Portuguese passport. They are Africans, rather than members of the diaspora. Moreover, most of the diaspora members do not call themselves that. They just call themselves artists. Finally, Portugal lacks a critical background like the one you will find in France or England, with centers, long-lasting platforms, and so on. Here we lack theoreticians, artists, and critics for writing the history of Lusophone African contexts in the arts—the theory is still arising. However, in our programming, we work with young researchers and with the Centro de Estudos Comparatistas of the University of Lisbon to open a critical dialogue around those issues. In any case, helping the community surrounding us is our main goal, although that is not an easy task. We want to have a voice in the process of rethinking the cultural background of Lisbon and Portugal. We seek to open new paths for different people to have access to art, for that it is necessary to first develop educational efforts. I guess things will start from there.

Carlos Garrido Castellano is an FCT Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Center for Comparative Studies of Lisbon University. His research interests focus on the visual culture and contemporary art of Atlantic and European postcolonial contexts. He currently coordinates the “Comparing We’s: Collectivism, Emancipation, Postcoloniality” research group.

Bruno Leitão is a Portuguese curator, living and working between Madrid and Lisbon. He is a board member and Curatorial Director at Hangar.

Mónica de Miranda is an artist and researcher. Born in Portugal to Angolan parents, her work is based on themes of urban archaeology and personal geographies. She is a founder of Hangar.

Notes

[1] These include Um oceano inteiro para nadar (2000), Looking both Ways: Das esquinas do olhar (2005), Réplica e Rebeldia (2006), De Malangatana a Pedro Cabrita Reis (2009), Fronteiras (2010), and Artistas Comprometidos? Talvez (2014). For a critique of this process, see Fernandes Dias (2006) and Costa Dias (2009). Individual exhibitions included Pieter Hugo, Ângela Ferreira, António Ole, Kiluanji Kia Henda, and Renée Green. See Rosengarten (1998) and Balona de Oliveira (2016).

[2] The ArtAfrica project (http://artafrica.letras.ulisboa.pt/pt/) developed in the early 2000s is a precursor of the initiatives arising in the last years. It systematically covers the entire range of Portuguese-speaking African countries. Alda Costa (2013) is author of the most exhaustive monograph on the matter. The bibliography on visual arts is, in any case, substantially smaller than that existent on music or literature.

[3] http://www.hangar.com.pt/en/about/

[4] Among them we can mention the University of Lisbon, the publishing house Orfeu Negro, and Artéria: Arquitectura e Reabilitaçãoo Urbana.

[5] Located on top of Mouraria and the Lisbon castle, Graça is actually part of the Freguesia (territorial demarcation) de São Vicente. The quarter is known for maintaining a large number of locals and for being close to the areas of Martim Moniz and Intendente, two major areas inhabited by migrants.

Bibliography

Balona de Oliveira, Ana, 2016. “Descolonização em, de e através das imagens de arquivo “em movimento” da prática artística” Comunicação e Sociedade 26: 107-131.

Bastos, Cristina; Vale de Almeida, Miguel; Feldman-Bianco, Bela, coords., 2002. Trânsitos Coloniais: Diálogos Críticos Luso-Brasileiros. Lisbon: Instituto de Ciências Sociais.

Castelo, Cláudia, 1998. “O modo português de estar no mundo.” O luso-tropicalismo e a ideologia colonial portuguesa (1933-1961). Porto: Afrontamento.

Costa Dias, Inês, 2009. “Curating Contemporary Art and the Critique to Lusophonie,” Arquivos da Memória. Antropologia, Arte e Imagem, 5/6: 6-46.

De Sousa Santos, Boaventura, 1993. “Modernidade, Identidade e a Cultura de Fronteira,” Revista crítica de ciências sociais, 38: 11-37.

De Sousa Santos, Boaventura, 2002. “Entre Prospero e Caliban: Colonialismo, pós-colonialismo e inter-identidade,” in Ramalho, Irene and Ribeiro, Antonio Sousa, orgs., Entre ser e estar. Raízes, percursos e discursos da identidade. Porto: Afrontamento, 23-85.

Fernandes Dias, Antonio, 2006. “Pós-colonialismo nas artes visuais, ou talvez não,” in ‘Portugal não é um país pequeno.’ Contar o Império na pós-colonialidade, ed. Manuela Ribeiro Sanches Lisbon: Cotovia, 317-339.

Ribeiro Sanches, Manuela, 2006, ed. “Portugal não é um país pequeno”. Contar o Império na pós-colonialidade. Lisbon Cotovia.

Ribeiro Sanches, Manuela; Clara, Fernando; Ferreira Duarte, João and Pires Martins, Leonor (eds.), 2011. Europe in Black and White. Inmigration, Race, and Identity in the “Old Continent.” Bristol: Intellect.

Rosengarten, Ruth, 1998. “Out of Africa: Um Olhar sobre as relações entre a arte contemporânea em Portugal e Africa,” Belem, Autumn/WInter.

Vale de Almeida, Miguel, 2000. Um mar da cor da terra. Raça, cultura e política da identidade. Oeiras: Celta.