The Arts and Crafts of Participatory Reforms: How Can Socially Engaged Art and Public Deliberation Inform Each Other?

Caroline W. Lee

The “arts world” is rarely mentioned in the world of civic engagement. That can and should change. The “arts person” is as narrow and false a conception as is the civic person. Public artists are gaining more experiences in creating the conditions that help nurture and sustain civic dialogue. Organizers of civic dialogue are finding ways to engage large numbers of community members in sustained democratic discussion. We need to find one another—across the nation and in our communities—and work together in more intentional ways. That will weave a lustrous community fabric and bring innumerable benefits to our public life. [Martha McCoy, Executive Director, Study Circles Resource Center (1997: 9)]

Nearly two decades after McCoy’s call for greater connections between those in the arts and those working to facilitate public dialogue, there is plenty of evidence that the arts world and the world of civic engagement have embraced each other over the intervening years. At its 2006 conference in San Francisco, the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation, the leading professional association for dialogue practitioners, abounded with sessions led by artists, founders of socially engaged art organizations, and staff from Americans for the Arts. The conference was enlivened by artmaking activities, graphic recording, spoken word and theater performances, an interactive public art project led by an artists’ collaborative from New York, and an invocation from a Brazilian drumming group that “performed songs and chants for Elegua, the Ancient African Deity of the Crossroads – the Opener of Dialogue and Communication!” (NCDD 2015). Arts practitioners had in turn embraced the expertise and special skills of professional public engagement consultants. The 2008 National Performing Arts Convention in Denver, a multidisciplinary convening of national service organizations in the nonprofit performing arts, hired AmericaSpeaks, the flagship dialogue and deliberation facilitation organization in the United States, to run a multi-day caucus process and 21st Century Town Hall Meeting for participants to develop their own collective action agenda for the performing arts.

Interchange between practitioners in the two fields is now a longstanding reality in the U.S., with many of the fruits that McCoy anticipated. The fields of scholarship on socially engaged art and deliberative democracy have developed alongside both areas of interest, with a wealth of case studies of successful initiatives, evaluations of impacts, and critical literature on the popularity of arts-based civic initiatives or deliberative democratic reforms in neoliberal times. By comparison with practitioner interactions across the two fields, however, the scholarly literature on arts-based civic dialogue and deliberative democracy have had minimal overlap thus far.

This essay is motivated by a conviction that the literature on democratization trends across other institutional fields could benefit from deeper engagement with the literature on socially engaged art, as represented by the critical discourse initiated in FIELD, and vice versa. This is not only because art has been actively employed in participation initiatives not directly related to the arts, but also because civic engagement professionals and socially-engaged arts practitioners have themselves embraced each others’ efforts over the last three decades. Drawing on a multi-method ethnography of the development of the public engagement field (Lee 2015), I sketch the evolution of scholarly and practitioner discourse to illustrate the ways in which the arts have been used strategically in civic dialogue and the ways civic dialogue has been incorporated as a goal into arts promotion and programming, while research in both fields has followed parallel, but rarely intersecting paths. Finally, I argue that critics of the new public participation and of socially engaged art should explore together their overlapping concerns regarding the dynamic relationship between participatory reforms and arts initiatives and their multiple, ambiguous outcomes.

Methods and Theoretical Approach

This essay draws on a five-year multi-method, multi-sited ethnography of the public engagement field, including participant observation at a number of public engagement conferences such as the NCDD meeting described in 2006, and as part of a research team on the 2008 National Performing Arts Convention. An in-depth sociological field study was conducted by the author from 2006 through 2010 at sites in major cities in the U.S. and Canada.[1] Extensive participant observation in various training and certification venues and professional conferences and over fifty informal interviews with diverse actors in the field provided perspective on the shared concerns and conflicts of deliberation practitioners regarding professional development and field advancement.[2]

For those unfamiliar with the terminology of public engagement and deliberative democracy, it is useful to begin by better specifying the loose boundaries of the field itself. “Professional public engagement facilitation” is used in this essay to refer to facilitation services aimed at engaging the public and relevant stakeholders with organizations in deeper, more interactive ways than traditional, one-way public outreach and information. The terms “public participation,” “civic engagement,” “public engagement,” and “public deliberation” are typically used interchangeably to refer to the broad spectrum of reforms aimed at intensifying public engagement and deliberation in governance, and this essay uses all of these terms in order to reflect their overlapping usage by practitioners. Executive director of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium Matt Leighninger notes that: “In common usage, ‘deliberation and democratic governance’ = active citizenship = deliberative democracy = citizen involvement = citizen-centered work = public engagement = citizen participation = public dialogue = collaborative governance = public deliberation. Different people define these terms in different ways – and in most cases, the meanings are blurry and overlapping” (Leighninger 2009: 5). “Profession” is used to refer specifically to organizations and educational institutions offering training and degree programs, trained practitioners paid for their work in public engagement facilitation, and their professional associations and occupational networks. “Field” refers to professionals, volunteer facilitators, facilitation clients and process sponsors, but also more broadly to the academics, institutes, foundations, and other organizations that share a common language, set of practices, and interest in advancing civic engagement and deliberation.

Half of U.S. professionals in the 2009 practitioner survey described their organizational role as an independent consultant or sole practitioner.[3] These public engagement consultants sell their services to a wide variety of clients for different issues, including local and regional governments and community development corporations, non-profit organizations, businesses, chambers, and industry trade groups. “Clients” with whom practitioners work directly to design processes may actually be separate from the “sponsors” who are underwriting deliberation. Foundations, community development corporations, and individual civic boosters play major roles, but newspapers, television networks, banks and mortgage lenders, utilities, health systems, universities, and residential and commercial developers also sponsor or underwrite public deliberation efforts on a regular basis (Lee 2015a).

Public engagement professionals may combine a variety of deliberative, dialogic, and participatory methods and techniques over the course of a particular project. They might convene a working group of major stakeholders for a series of meetings, produce an interactive website and host a series of online dialogues, or design and host a town hall meeting where participants share ideas in small groups and then vote on the options that have been developed. The responsibilities of the public engagement consultant typically involve all aspects of process design and implementation, including production of informational and marketing materials, stakeholder outreach prior to the process, selection of methods, recruitment of participants and small group facilitators, facilitation of the overall process, continued communication with participants, presentation to the client of process outcomes, and evaluation of process efficacy. Some aspects of these tasks, such as recruitment of underrepresented groups, process branding, and software design, may also be outsourced to subcontractors like opinion research firms and marketing firms for large projects, but most contractors provide the complete range of process design and facilitation services from inception to evaluation, which may last from a few months, in the case of public engagement on pandemic flu planning priorities, to ten years or more in the case of stakeholder collaborations on contaminated sites remediation or natural resource management.

By comparing data from a variety of settings, sources, and perspectives, this type of qualitative research across institutional domains and participant categories “looks to the logics of particular contexts as a way of illuminating complex interrelationships among political, legal, historical, social, economic, and cultural elements” (Scheppele 2004: 390). As such, this research was conducted from the perspective of a comparative historical sociologist interested in the development of the field in the context of concurrent processes of U.S. political development, rather than from the standpoint of advancing deliberation practice or theory (Mutz 2008). The essay is by no means comprehensive in its descriptions of deep, long-term relationships between arts and civic engagement practitioners, but instead sketches three key moments in the evolution of these relationships, beginning with the promise McCoy foresaw in the 1990s.

Imagining the Potential of Arts and Civic Dialogue in the 1990s

Of course, both public engagement and socially engaged art have long histories in the United States, and plenty of work traces the genealogies of these practices and their changing meanings over time (Gastil and Keith 2005; Jackson 2011; Lippard 1984; Reed 2005; Stimson and Sholette 2006; Thompson 2012; Walker et al. 2015). What was unique in the late 20th century, however, was the professional and formal organization of these fields as arenas for strategic and coordinated action (Fligstein and McAdam 2011; Zald and McCarthy 1980). This “veritable revolution… in the formation of organizations and a ‘profession’ devoted to the participation of ordinary citizens” produced an extensive “organizational infrastructure for public deliberation” (Jacobs, Cook, and Delli Carpini 2009: 136). The field of professional public engagement was just getting underway in the early 1990s, with the International Association of Public Participation Practitioners (later shortened to IAP2) founded in 1990. The National Coalition on Dialogue and Deliberation was founded later in 2002, as the field began to focus not just on engaging the public but on “dialogue and deliberation”—the value of reason-giving conversations among equals for public problem-solving.

Professional facilitators’ increasing focus on collaborative dialogues coincided with a wave of enthusiasm in the academy for “deliberative” democracy, inspired by a number of experiments in consensus-building and collaborative decision-making in environmental planning, community mediation, and alternative dispute resolution in the 1970s and 1980s (Lee 2015). Fatigue with increasingly adversarial techniques of oppositional activism and partisan posturing in popular media intersected with the interests of new public managers in empowering communities by devolving decision-making to the local level (Handler 1996). Public deliberation, as a new civic form that brings together interest group representatives, activists, and laypersons as equal participants in decision-making sponsored by administrators, foundations, and businesses, also reflects the professionalization of activism, the reframing of corporate citizenship, and the increasing cross-sector collaborations that characterized organizational politics and strategy in this period (Ansell and Gash 2008; Lee, Walker, and McQuarrie 2015; Soule 2009; Zald and McCarthy 1980).

Likewise, a sense of coalescence around the promise of arts-based civic dialogue was also taking place in the 1990s, with greater institutional and professional support than had previously been given to artists advancing performative techniques of audience engagement and activist art in the 1970s and 1980s (Gonzáles and Posner 2006). Just as was the case with civic funders in the dialogue and deliberation field, there was a sense developing among arts funders—some of which, like the Ford Foundation, funded projects in the arts and in public engagement—that civic dialogues were a promising solution in an atmosphere exhausted by the “culture wars” of the 1980s and state-level disinvestment in the arts (Katz 2006; Tepper 2010).

A key moment that crystallized the potential of such dialogues for both the arts and for public engagement were the riots following the acquittal of officers in the Rodney King police brutality case in Los Angeles in 1992. These were the inspiration for Anna Deavere Smith’s “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” a theater piece incorporating community members’ perspectives that gained national acclaim and spawned a number of civic dialogues on its performance in cities around the U.S. Additional tensions following the Simpson trial verdict in 1995 contributed to the founding of the Days of Dialogue organization by LA City Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas. Also in 1995, Carolyn Lukensmeyer founded AmericaSpeaks, following her service in the Clinton administration. In 1997, the Clinton administration launched Clinton’s One America Initiative on Race, initiating multi-city Days of Dialogue and 600 Campus Weeks of Dialogue with the help of public engagement organizations like Martha McCoy’s Study Circles Resource Center and the National Days of Dialogue organization. The report on the One America Initiative describes “18,000 people in 36 States, 113 cities, and the District of Columbia” taking part in approximately 1,400 One America Conversations (One America Advisory Board 1998).

Capitalizing on experiments and innovations in both fields throughout the mid-90s, the Ford Foundation and the leading U.S. arts advocacy organization, Americans for the Arts, released a long-awaited report titled “Animating Democracy: The Artistic Imagination as a Force in Civic Dialogue” in 1999. The 138-page report described a multi-year study from 1996-1998 highlighting promising and innovative cases of arts-based civic dialogue across different genres and with all kinds of sponsors—from a Chrysler-sponsored multi-city discussion initiative around the PBS broadcast of “Hoop Dreams,” to collaborative, community-centered theater and dance projects initiated by playwrights and artists.

In a context of mounting concerns about public cynicism and apathy in the U.S. and increasing pressure on elite arts institutions to diversify their offerings, the report focused not on the potential of art for critical social commentary or of arts institutions and artists in mobilizing contention and protest, but on the civic productivity of “a vital midrange of activity”: “In this work, art consciously incorporates civic dialogue as part of an aesthetic strategy” (Bacon et al. 1999: 30). This explicitly non-partisan activity, with its capacity for activating the dormant creative potential of citizens and audiences, was seen as a promising and civil arena for engagement. Arts-based civic dialogue projects seemed an uncontroversial solution for tackling the most difficult social justice issues.

A closer look at the Animating Democracy Report reveals two important aspects of the development of both fields through interaction and experimentation. First, foundations were central to encouraging interaction among leaders in both emergent fields (Medvetz 2010).[4] The report included the participation of dialogue and deliberation organization founders such as Martha McCoy of Study Circles Resource Center (now Everyday Democracy), James Fishkin, the inventor of deliberative polling, and the Kettering Foundation, the central research organization in the civic engagement field. The authors even included examples of civic dialogue processes run by professional public engagement organizations that were not specifically related to the arts or arts institutions at all. They also were careful to note that arts-based dialogues could fail to recruit diverse participants, cause controversy, or have minimal impact without the engagement of skilled facilitators with local knowledge and the ability to recruit diverse audiences and manage sustained conversations among people with clashing perspectives.

Second, as an effort to map the field, the report is notable in its inclusive approach to for-profit entities and all kinds of popular arts and media that might conceivably fall under the banner of arts-based civic initiatives. This heterogeneity is typical of emerging fields, and as we will see in the following section, was subject to convergence in the following decade as both fields began to consolidate best practices and exhibited considerable isomorphism in the ways largely nonprofit and elite arts institutions integrated the arts and dialogue into their practices (Mizruchi and Fein 1999).

The report sketched a blueprint for future collaborations, leading to the formal launch of Americans for the Arts’ Animating Democracy Initiative in 1999, and concluded that the timing was perfect for such activity:

In sum, the current moment represents a critical juncture for the arts-based civic dialogue field: There is increasing recognition of the importance of dialogue to democracy; a lively array of artistic activity and aesthetic innovations are nourishing dialogue on a wide range of critical issues; there is growing institutional interest in this arena; and a clearer picture of the accomplishments, promise, and needs of this field and its leaders has begun to take shape. Taken together, these trends signal an important opportunity to strengthen and invigorate critical aspects of America’s civic and aesthetic life. It is a timely moment to bolster the position of artists, curators, and cultural institutions whose imagination has proved a potent force in animating democracy through the arts and civic dialogue. (Bacon et al. 1999: 64)

As we will see in the next section, as arts-based civic dialogues were further institutionalized and as the arts were incorporated into public deliberation projects in more formulaic ways, both fields saw promising forms of expansion from unlikely places of support. But they also faced new challenges and critiques from those concerned about the ways in which top-down promotion of grassroots citizenship might contribute to reinforcing the power of neoliberal institutions rather than challenging them.

Institutionalizing the Arts and Civic Dialogue in the 2000s: Challenge and Critique

“Woo-woo,” she blurted, matter-of-factly. “Y’know, that touchy-feely arts stuff.” She was polite, but matched the sing-songy word with a cringing smile. “We won’t have to do that, will we?”[Jon Catherwood-Ginn and Bob Leonard, Animating Democracy trend paper, 2012]

The aesthetic strategies of the counterculture: the search for authenticity, the ideal of self-management, the anti-hierarchical exigency, are now used in order to promote the conditions required by the current mode of capitalist regulation, replacing the disciplinary framework characteristic of the Fordist period. Nowadays, artistic and cultural production play a central role in the process of capital valorisation and, through ‘neo-management’, artistic critique has become an important element of capitalist productivity. [Chantal Mouffe, “Art and Democracy,” 1998]

In hindsight, the Animating Democracy Report was prescient regarding an explosion of participatory activity in the 21st century. The kinds of participatory reforms that were becoming popular in the arts and civic dialogue in the 1990s diffused quickly across many institutional fields in the 2000s, with invitations to “Join the conversation!” and “Have your say!” becoming commonplace in corporate workplaces, community organizations, schools, houses of worship, and governments (Lee 2015b). This popularity brought new energy, new resources, and new partners to both fields, enabling further development of professional identities and livelihoods, but also a number of growing pains and other consequences typical of developing fields, including anxieties on the part of both scholars and practitioners about potential cooptation pressures (Hendriks and Carson 2008), and pushback from everyday participants resistant to the “touchy-feely” integration of arts in decision-making and community development processes (Lee 2015a).

Just as “new genre public art” seeks to escape the conventions of public art but nevertheless has a mappable terrain (Lacy 1994), so too have arts-based civic dialogue projects begun to develop genre conventions (Finkelpearl 2013; Helguera 2011; Kester 2015a; 2015b)—among them shared techniques of small group dialogue, audiences accustomed to invitations to participate, and interactive theatrical performances incorporating participation and testimonials from everyday people—the latter particularly ripe for appropriation in commercial marketing given their association with unfiltered authenticity.

As deeper participation was becoming taken for granted in contemporary artmaking, critics interrogated whether it really represented a radical challenge to the status quo. Bishop (2006; 2012) questions the insistent moral boosterism that has accompanied participatory art projects and calls for a systematic reevaluation of the democratic empowerment thought to result. Voeller describes a sleight of hand in the discourses of empathy and community spirit that many processes draw upon, despite their implicit reliance in funding and publicity on development logics focused on the needy:

That reality is co-constructed through communal participation is typically a jumping off point, even if a tacit one, for artistic endeavors that seek to effect social change and build solidarity. However, with varying degrees of intention, such projects operate on the basis of social difference more than commonality. They leverage the privilege of an artist and his or her access to capital of some kind—class, gender or racial privilege; cultural or reputation capital; funding or fundability—to extend resources to a community that does not have access to the same, frequently due to real and persistent inequity. (2015: 277)[5]

Further, critics wondered about the ways in which forms like immersive theater privileged particular kinds of “entrepreneurial participation” and the “valorization of risk, agency, and responsibility” on the part of audience members—making immersive theater “particularly susceptible to co-optation by a neoliberal market given its compatibility with the growing experience industry” (Alston 2013: 128).

Dialogue and deliberation techniques quite intentionally became focused on a limited palette of best practices and core principles in the same period, with practitioners determined to prove to decision-makers and leaders that such practices worked and were worth institutionalizing more deeply in all forms of governance (Glock-Grueneich and Ross 2008; NCDD et al. 2009; Zarek and Herman 2015). Formalized trainings for process design and implementation were offered not only by professional organizations and methods organizations, but also by organizations like the Kettering Foundation’s National Issues Forums Moderator Trainings, leading to the consolidation of facilitation principles and techniques.

As such, public deliberative forums using different methods may look superficially heterogeneous, but have predictable formats that are instantly recognizable for veterans—round tables, a visioning exercise to get started, an initial discussion to decide core values and procedures, break out sessions, a return to the large group, “popcorn-style” reports and process summaries, and a reflective finale (Lee 2011). Most public deliberative processes incorporate some combination of hands-on discussion aids such as table facilitators, talking sticks, sketching on butcher block paper, strategy games, or index card sorting in small group dialogues. For large groups, high- or low-tech tools such as keypad polling, “dot” voting with stickers, or online voting aggregate the results of small group dialogues. Art created by professionals and amateur artmaking are routinely integrated— in invocations using slam poetry and drumming, in graphic recording by visual artists of key phrases and images on large reams of paper, in group drawing exercises using children’s art materials—in public engagement processes.

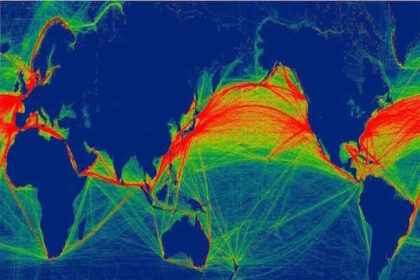

In fact, the power of art, music, and spontaneous transformations has become central to what transpires in facilitated public engagement—in part because these processes and their emphases on “getting things done” have become so routine. The integration of art, poetry, and music has come to symbolize the infusion of creativity, critique, and contingency into processes that are otherwise meticulously planned. Having participants themselves use art to express themselves draws on tropes from art therapy, helping participants to connect with and share their own emotions (Roy 2010; Whittier 2009). In line with facilitators’ goals of encouraging authentic, human connections and value-oriented communication over position-taking, drawing is intended to tap “inexpressible” feelings and beliefs, forcing participants to use their creative “right brains” instead of their critical “left brains.” For instance, Conversation Cafés provide crayons and butcher paper at tables just to get the juices flowing, whereas more intentional exercises use drawing to produce illustrations of a front page of a newspaper in an imagined future. The humble materials used—markers, pipe cleaners, crayons—put participants into a childlike setting of “play” rather than work (See Image 1, a collaborative art project produced from recycled materials by public deliberation practitioners at an NCDD conference). Participants also have the experience of contributing a “piece” of themselves when creating art, reaching a deeper level of engagement than simply listening silently or voicing support for others’ views. Posting the art on the walls of meeting rooms provides an opportunity for participants to tour others’ self-expression and to feel they have been heard and seen.

This sense that art is valuable for the creativity and collaborative innovation it can stimulate is repeatedly invoked as a justification for artful interventions in public engagement. The uses of art in public engagement draw on a particular idea of art as playful and fun, which releases participants from competitive, anxious mindsets and enables them to achieve higher levels of performance, collaboration, and expressive potential as individuals. These elements of individual participation and action are increasingly documented as key to economic accountability and efficiency, because passive consumers are transformed into active citizen collaborators (Lee, Shaffer, McNulty 2013).

Nina Eliasoph describes in her work on Empowerment Projects similarly routine uses of art in public events and fairs intended to “celebrate our diverse, multicultural community” (2011: 206). Diversity fairs “could not celebrate disturbing or puzzling differences, and frowned upon making distinctions among people anyway,” instead convening a jumble of noncontroversial offerings such as food and dance, gospel music, drumming, poetry readings, glitter and glue projects for children, and craft booths—all competing for attention. Similarly, I argue in Lee (2015) that the art used on a routine basis to stimulate or enhance lay participation typically employs a wide range of genres but a small scope of fleeting, individualized actions. Collaborative art projects and group performances in these contexts are oriented to emotion management, individualization of grievances, and temporary, symbolic expressions of group unity in collective art projects where each person contributes a small piece to a larger collage or mosaic. By incorporating art into their dialogues, engagement practitioners celebrate community and contest the rationalizing logics of the market. But they also claim that creative art-making is strategically useful for producing the intended effects of dialogue, improving comprehension of technical topics and producing “results in record time.”

These instrumental uses of art can certainly be harnessed to the aims of neoliberal retrenchment (succinctly summed up by one proponent of the cost-savings enabled by deliberation as “pluck[ing] more feathers with less squawking,” [Zacharzewski 2010:5]). As deliberation and dialogue were institutionalized, activists and scholarly critics of public engagement initiatives increasingly noted the limitations of the empowerment on offer in participation initiatives in the late 1990s and 2000s. Coming in for particular excitement, and later disappointment, were the Obama Administration’s Open Government Initiatives, which called for government to be more participatory, collaborative, and transparent, but focused largely on online feedback tools in practice (Buckley 2010; Koniescka 2010; Wolz 2011). Scholars in Australia, the US, and the UK derided “fake” participation and the ways it might reinforce the power of state and corporate actors by containing critique and protest (Atkinson 1999; Head 2007; Kuran 1998; Leal 2007; Levine 2009; Snider 2010).

Likewise, Kester notes that critics of socially engaged art have linked “local, situational or ‘ad hoc’ actions… to systematic forms of domination. A typical reproach directed at projects of this nature is that they function as little more than window dressing for a fundamentally corrupt system” (2015b). In an essay on an alternately critical and anodyne 2014 conference on social practice art in Chicago, Voeller describes “the historical dependence of forms of avant-garde art, now including social practice, on a golden umbilical cord of market and institution support” (2015: 279) and the challenge posed in one presentation:

Daniel Joseph Martinez put his time to the best critical use: he called on the group to stop conflating social practice with doing good and to develop better means of evaluating work under this problematic label. “This is a back alley fight for history,” he warned. (278)

Tensions in the “community arts” world described in a 2011 trend report from Animating Democracy include positive economic and developmental outcomes to remediate social problems (“improved economies, academics, and self-esteem; the reduction of violence and recidivism; and an increase in employment and community cohesiveness”), but also a number of failed projects initiated by large investments from foundations and philanthropies that have destabilized and disrupted communities and “damaged” artists (Cleveland 2011: 7). The author warns that a focus on aesthetic value and quality should predominate over instrumental interests: “The most successful programs have been developed by artists making art, not artists doing something else. These artists have created art programs, not therapeutic or remedial programs that use art as a vehicle” (7).

There have been many critiques of projects intended to deepen public and community engagement in the 2000s and 2010s for their failures to mobilize and inability to contest the status quo, both in the arts community and in the public engagement community.[6] Not least, publics accustomed to thin participatory routines may push back, as when arts-based dialogue leaders face woo-woo moments such as the one that begins this section, or when members of communities see “invitations” to participate as pressuring poor people to self-sacrifice even further (Herbert 2005: 850). Some of the potential for empowerment in these projects is certainly lost as interests in community development and socially engaged art intersect to strengthen institutions and elites rather than communities and to legitimize neoliberal retrenchment.

Contextualizing Critics of the Arts and Civic Dialogue in the 2010s

While an uncritical vocabulary of ‘participation’ has proliferated in both cultural and regeneration policy, the actual practice on the ground reveals significant difficulties which have implications for policy goals of community participation and empowerment, and for the community itself. Rather than seeing it as a problem, or something to be removed as soon as possible from the process, contestation and conflict should be recognised as appropriate reflections of community. [Venda Louise Pollock and Joanne Sharp, “Real Participation or the Tyranny of Participatory Practice? Public Art and Community Involvement in the Regeneration of the Raploch, Scotland” (2012: 3063)]

Even with growing successes in democratic innovation and practice, and with meaningful results from those practices, we haven’t even come close to affecting the daily lives of most people… With our democracy in crisis, our field is engaging in more collaborative efforts and in more pointed and urgent conversations about how to have a systemic impact. [Martha McCoy, “The State of the Field in Light of the State of our Democracy: My Democracy Anxiety Closet” (2014: 1)]

As the chorus of criticism has grown louder, a number of scholars have noted that simply analyzing whether dialogue initiatives were “real” or “fake”, “worked” or “failed”, does not get at the multiple and ambiguous impacts of participation in these projects, nor the fact that mixed outcomes and contention around authenticity have long been the result of participatory reforms (Selznick 1949; Polletta 2015a). Participation has increased at the same time that social and economic inequality has increased, but the complex relationships between these trends must be examined empirically (Lee et al. 2015). Amidst continuing criticisms of the overinflated hype that has accompanied “The Great Consultation”, or the “Age of Engagement” (Martin 2015; Edelman 2010), practitioner attention and some scholars have shifted away from either/or evaluations to consider what meanings are attached to contemporary civic dialogue and socially engaged art initiatives today, and how to confront the unintended consequences of stability and settlement in both fields.

In a 2014 issue of the Journal of Public Deliberation, leading practitioners and scholars including McCoy debated the state of the field and possible paths for the future in the face of great progress but also limited impact. In the journal FIELD and other academic venues, artists and scholars of socially engaged art (like Pollock and Sharp quoted above) have similarly contemplated a way forward, seeking “to develop a pragmatic analysis that can help us understand how the forms of critical, self-reflective insight that we have come to identify with aesthetic experience can be produced in contexts and through forms of cultural, social or institutional framing, quite different from those we associate with conventional works of art” (Kester 2015a: 4). This section specifies two areas of overlap in these emerging investigations of how to move forward in advancing their respective fields, both within and beyond their current limitations.

- Putting short-term or ad hoc projects in longer-term contexts of reception and action

Deliberation expert Patrick Scully describes the limiting nature of the field’s emphasis on discrete projects:

Our field’s strong emphasis on temporary public consultations diverts a disproportionate amount of time, intellectual capital, and other resources from efforts to improve the ability of citizens and local communities to have stronger, more active, and direct roles in shaping their collective futures. (2014: 1)

Matt Leighninger, at the time Executive Director of the Deliberative Democracy Consortium, finds that, on the one hand, participants “enjoy” democratic participation and “value these opportunities to be heard” despite the fact that democratic tactics “are rarely sustained or embedded” (2014: 2-3). Deliberation researchers conducting follow-up studies report that participants may evaluate processes positively in the moment, but be frustrated by limited impacts or even forget participating as their busy lives continue. As one participant at the 2008 National Performing Arts Convention reported just a month after the meeting:

To me, it was an exciting and intellectually stimulating experience. Very intense but valuable. Although when I got home that energy dissipated which I’m sure was true for most. So the challenge is to keep that focus and build on the energy… The dialog needs to continue. It must continue for something to happen… Not that it merited intense journalistic scrutiny but it’s almost like it never happened. And to the nation, to individual people – the people we want to bring to the arts – it really didn’t.

Similarly, Kester calls in his inaugural editorial for FIELD for “a critical analysis that can gauge the long-term effects of socially engaged practices” and, relatedly, “mechanisms to incorporate the insights of participants and collaborators involved in specific projects” (2015a). In two of the socially engaged projects described in the first issue, journal staff had not yet been able to track down participants. Such difficulties promote empathy for the hard work of artists and deliberation facilitators who may be deeply committed to longer-term engagement but hamstrung by conflicts between institutional pressures for short-term accountability and the lived experience of everyday time pressures in participants’ lives (Eliasoph 2011).

- Better understanding the relationship between local or community-level art projects and dialogue initiatives and systemic, structural change in complex systems.

Public engagement scholar Peter Levine argues that “rising signs of oligarchy in the United States” mean “it is time for us to begin to stir and organize—not for deliberation, but for democracy” (2014: 3), while Patrick Scully sees a central tension in deliberative practice “between reformism and more fundamental, even revolutionary changes to democratic politics” (2014: 1). Leighninger describes how the “lack of a clear vision about the relationship between our work and the political system has dire consequences” (2014: 2).

The public deliberation field has historically had a fraught relationship with activism to redress structural inequalities given deliberative democracy’s emphasis on consensus, civility, and non-partisanship (Lee 2015; Whelan 2007), but recently practitioners have called for more intentional linkages between dialogue, action, and even advocacy. Researcher Francesca Polletta explores a number of tensions and claims that “alongside those tensions, however, there are also strong continuities of interest”: activism and deliberation may not just be compatible, but “sometimes they may be necessary to each other” (2015b: 240). Kester (2015b: 1-2) similarly argues against simplistic critiques of socially engaged art as inadequate in overthrowing the capitalist system, especially:

The assumption that any given art project is either radically disruptive or naively ameliorative (trafficking in “good times, affirmative feelings and positive outcomes” as a typical blog posting describes it). This is paired with the failure of many critics to understand that durational art practices, and forms of activism, always move through moments of both provisional consensus or solidarity formation and conflict and disruption.

Instead, Kester proposes, putting socially engaged art projects in their proper context requires grasping “the generative capacity of practice itself—its ability to produce new, counter-normative insights into the constitution of power and subjectivity” (2015b: 2).

In a similar vein, a developing form of scholarship in studies of deliberation seeks to understand participation “in the context of shifting relationships between authority, voice, and inequality in the contemporary era” (Lee 2015b: 272) by “blending micro-level cultural studies of democracy with macro-level political-economic inquiry”—including “objective analysis of the role of organizations and scholarship itself in promoting the new public participation” (278-279). Baiocchi and Ganuza, for example, trace the diffusion of participatory budgeting in 1,500 cities around the globe, analyzing the precise ways in which “real utopian” social transformation was stripped from the technical implementation of the practice as it traveled—and providing “suggestions for reintroducting empowerment” (2014: 29). At the same time that these studies acknowledge shortcomings and disappointments in public engagement processes, they also welcome “pointed and urgent conversations,” awkward moments and tensions as productive sites for exploration and growth.

A Call for Greater Dialogue on the Related Challenges of Public Deliberation and Socially Engaged Art

Many people who describe themselves as community organizers see our field as simply an alternative form of advocacy – one that emphasizes friendly, urbane conversations and suppresses questions of power. Ironically, when I interviewed leading community organizers, I found they had the same frustrations about the limitations of their work, and the same zeal to transform systems, as I do. (Leighninger 2014: 3)

It is important not to overstate similarities in the ways these two related fields pursue their work. As Kester notes, socially engaged art is distinguished by its “extraordinary geographic scope” and “a common desire to establish new relationships between artistic practice and other fields of knowledge production, from critical pedagogy to participatory design, and from activist ethnography to radical social work” (2015a: 1). By contrast, Leighinger points out that the civic engagement field has struggled to define itself against related practices and has been relatively provincial in its networks: “Participation advocates and practitioners in the Global South, who have pioneered Participatory Budgeting and many other dynamic (and in some cases, sustained) forms of participation, do not sense a similarly democratic energy in the countries of the North – and many of us in the North do not realize how much we can learn from civic innovations in the South” (2014: 3). Additionally, the uses of arts in the professionally-facilitated dialogues described here frequently emphasize a reductive take on art as a simplistic, largely disposable and instrumental type of “play”, while not surprisingly, the art produced by socially engaged artists quite intentionally challenges conventional understandings of aesthetics and audiences. These conflicting approaches should not be overlooked, but as Leighninger notes with respect to community organizers and public engagement professionals, deeper conversations reveal shared frustrations about the limitations of either approach.

It is the purpose of this essay to point out these shared areas of struggle, and perhaps to question presumptions about the assumed compatibility of art and social change (Lee and Long Lingo 2011)—particularly as represented in the dialogue and deliberation world’s embrace of particular forms of amateur craft production and participatory performance. This essay is a first effort at tracing moments of overlap or crossed purposes, not to critique the futility of social change efforts, but to encourage both artists and civic engagement practitioners to deepen their engagement with each other and to embrace the difficult conversations that might lead to more productive collaborations and more sustainable social change.

Caroline W. Lee is Associate Professor of Sociology at Lafayette College. Her research explores the intersection of social movements, business, and democracy in American politics. Her book Do-it-Yourself Democracy: The Rise of the Public Engagement Industry (2015) studies the public engagement industry in the United States. Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation (2015), an edited volume with collaborators Edward Walker and Michael McQuarrie, explores the challenges of “the new public participation”—the dramatic expansion of democratic practices in organizations—in an era of stark economic inequalities.

Notes

[1] See Lee (2015) for more detailed information on methodology and limitations.

[2] Analysis of deliberation practitioners’ listservs, organization and process websites, blogs, social networking sites, field handbooks, and unique data sources supplements the information gathered through participant observation (Small 2011). Listserv postings were collected, coded by source, and stored in a full-text, searchable database containing over 8,400 documents representing four years of electronic conversations on the field. As a supplement to the fieldwork, informal interviews, and archival research, a non-random online survey of U.S. dialogue and deliberation practitioners (N=345), distributed through over twenty online listservs and web-based community networks in the field, was conducted in September and October 2009 in collaboration with Francesca Polletta of the University of California, Irvine, in order to solicit a broader perspective on the dominant tensions and shared beliefs surfacing in the qualitative research. The survey, whose target population was volunteer and professional deliberation practitioners in the United States, yielded 433 completed responses, 345 of which were from respondents based in the United States. More information on the survey, including demographic information and full results, is available at the public survey results website (http://sites.lafayette.edu/ddps).

[3] N=222; see footnote 2 above for more information regarding the survey.

[4] This influence went both ways. Sirianni and Friedland’s Civic Innovation in America, a similar book-length project mapping the civic field of the 1990s, also thanked the Ford Foundation for their support of such efforts, both through their Reinventing Citizenship Project and the program in Media, Arts, and Culture (2001).

[5] Eliasoph (2011) describes similar clashes in youth empowerment projects that depended on celebrating community empowerment and volunteerism but also on preventing needy teens from becoming social problems.

[6] Similarly impassioned discourse characterizes these parallel critiques. Bishop’s provocative 2006 essay in Artforum on the “Social Turn” is subheaded “Collaboration and its Discontents” and her 2012 book is titled Artificial Hells; a 2014 blog for political sociologists interrogating the empowerment potential of civic initiatives was titled “Participation and Its Discontents” (Baiocchi et al. 2013) and a groundbreaking volume critiquing regimes of public engagement globally was titled Participation: The New Tyranny? (Cooke and Kothari 2001).

References

Alston, Adam. 2013. “Audience Participation and Neoliberal Value: Risk, Agency and Responsibility in Immersive Theatre.” Performance Research 18: 128-138.

Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18:543-571.

Atkinson, Rob. 1999. “Discourses of partnership and empowerment in contemporary British urban regeneration.” Urban Studies 36: 59–72.

Bacon, Barbara Schaffer, Cheryl Yuen, and Pam Korza. 1999. “Animating Democracy: The Artistic Imagination as a Force in Civic Dialogue.” Washington, DC: Americans for the Arts.

Baiocchi, Gianpaolo, Pablo Lapegna, Philip Lewin, and David Smilde. 2013. ‘Participation and its Discontents: A Scholarly Forum for Interrogating the Promises and Pitfalls of Political Participation.’ http://participationanditsdiscontents.tumblr.com/

Baiocchi, Gianpaolo, and Ernesto Ganuza. 2014. “Participatory Budgeting as if Emancipation Mattered.” Politics & Society 42: 29-50.

Bishop, Claire. 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. New York: Verso.

_____. 2006. “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents.” Artforum 44: 178-183.

Black, Laura W., Nancy L. Thomas, and Timothy J. Shaffer. 2014. “The State of Our Field: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): 1-5. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art1

Buckley, Stephen. 2010. “OpenGovRadio Today (2/2/10): ‘Engagement-Lite’ and the OpenGov Dashboard.” Blog post: February 2 (http://ustransparency.blogspot.com/2010/02/opengovradio-today-2210-engagement-lite.html).

Catherwood-Ginn, Jon, and Bob Leonard. 2012. “Playing for the Public Good: The Arts in Planning and Government.” Animating Democracy/Americans for the Arts. (http://animatingdemocracy.org/resource/playing-public-good-arts-planning-and-government)

Cleveland, William. 2011. “Arts-based Community Development: Mapping the Terrain.” Animating Democracy/Americans for the Arts. (http://animatingdemocracy.org/resource/arts-based-community-development-mapping-terrain)

Cooke, Bill, and Uma Kothari, eds. 2001. Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

Davis, Gerald F., and Mayer N. Zald. 2005. “Social Change, Social Theory, and the Convergence of Movements and Organizations.” Pp. 335–50 in Social Movements and Organization Theory, edited by Gerald F. Davis, Doug McAdam, W. Richard Scott, and Mayer N. Zald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duffy, Meghan, Amy Binder, and John Skrentny. 2010. “Elite Status and Social Change: Using Field Analysis to Explain Policy Formation and Implementation.” Social Problems 57:49-73.

Edelman. 2010. Public Engagement in the Conversation Age: Vol 2. London: Edelman. (http://edelmaneditions.com/2010/11/public-engagement-in-the-conversation-age-vol-2/).

Eliasoph, Nina. 2011. Making Volunteers: Civic Life after Welfare’s End. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Finkelpearl, Tom. 2013. What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Fligstein, Neil, and Doug McAdam. 2011. “Toward a General Theory of Strategic Action Fields.” Sociological Theory 29:1-26.

Gastil, John, and William M. Keith. 2005. “A Nation that (Sometimes) Likes to Talk: A Brief History of Deliberation in the United States.” Pp. 3-19 in The Deliberative Democracy Handbook, edited by John Gastil and Peter Levine. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ganuza, Ernesto, and Gianpaolo Baiocchi. 2012. “The Power of Ambiguity: How Participatory Budgeting Travels the Globe.” Journal of Public Deliberation 8:Article 8.

Glock-Grueneich, Nancy and Sarah Nora Ross. 2008. “Growing the Field: The Institutional, Theoretical, and Conceptual Maturation of ‘Public Participation.’” International Journal of Public Participation 2:1-32.

Gonzáles, Jennifer, and Adrienne Posner. 2006. “Facture for Change: US Activist Art since 1950.” Pp. 212-230 in A Companion to Contemporary Art Since 1945, edited by Amelia Jones. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Handler, Joel F. 1996. Down from Bureaucracy: The Ambiguity of Privatization and Empowerment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Head, Brian W. 2007. “Community engagement: Participation on whose terms?” Australian Journal of Political Science 42: 441–454.

Heierbacher, Sandy. 2015. “NCDD’s Year In Numbers infographic is out!” Blog post: January 5 (http://ncdd.org/17127).

_____. 2014. “The Next Generation of Our Work.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): Article 23. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art23

Helguera, Pablo. 2011. Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York: Jorge Pinto Books.

Hendriks, Carolyn M., and Lyn Carson. 2008. “Can the Market Help the Forum? Negotiating the Commercialization of Deliberative Democracy.” Policy Sciences 41:293-313.

Herbert, Steve. 2005. “The Trapdoor of Community.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95: 850-865.

Jackson, Shannon. 2011. Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics. New York: Routledge.

Journal of Public Deliberation. 2010. “Aims & Scope.” (http://services.bepress.com/jpd/aimsandscope.html).

JPD (see Journal of Public Deliberation).

Katz, Jonathan D. 2006. “‘The Senators Were Revolted’: Homophobia and the Culture Wars.” Pp. 231-248 in A Companion to Contemporary Art Since 1945, edited by Amelia Jones. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Kelleher, Christine A., and Susan Webb Yackee. 2008. “A Political Consequence of Contracting: Organized Interests and State Agency Decision Making.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19:579-602.

Kester, Grant. 2015a. “Editorial.” FIELD 1: 1-10.

_____. 2015b. “On the Relationship between Theory and Practice in Socially Engaged Art.” Posted on “Fertile Ground,” at A Blade of Grass (July)

http://www.abladeofgrass.org/fertile-ground/between-theory-and-practice/

Koller, Andreas. 2010. “The Public Sphere and Comparative Historical Research.” Social Science History 34:261-290.

Konieczka, Stephen P. 2010. “Practicing a Participatory Presidency? An Analysis of the Obama Administration’s Open Government Dialogue.” International Journal of Public Participation, 4:43-66.

Kuran, Timur. 1998. “Insincere Deliberation and Democratic Failure.” Critical Review 12:529-544.

Lacy, Suzanne, ed. 1994. Mapping The Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle: Bay Press.

Leal, Pablo Alejandro. 2007. “Participation: The Ascendancy of a Buzzword in the Neo-liberal Era.” Development in Practice 17: 539 –548.

Lee, Caroline W. 2011. “Five Assumptions Academics Make About Deliberation, and Why They Deserve Rethinking.” Journal of Public Deliberation 7(1): 1-48.

_____. 2015a. Do-it-Yourself Democracy: The Rise of the Public Engagement Industry. Oxford University Press.

______. 2015b. “Participatory Practices in Organizations.” Sociology Compass 9: 272-288.

Lee, Caroline W., and Elizabeth Long Lingo. 2011. “The ‘Got Art?’ Paradox: Questioning the Value of Art in Collective Action.” Poetics 39: 316-335.

Lee, Caroline W., Kelly McNulty, and Sarah Shaffer. 2015. “Civic-izing Markets: Selling Social Profits in Public Deliberation.” Pp. 27-45 in Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation, edited by Lee, McQuarrie, and Walker. New York: NYU Press.

Lee, Caroline W. and Zachary Romano. 2013. “Democracy’s New Discipline: Public Deliberation as Organizational Strategy.” Organization Studies 34: 733-753.

Leighninger, Matt. 2009. “Funding and Fostering Local Democracy: What Philanthropy Should Know about the Emerging Field of Deliberation and Democratic Governance.” Denver, CO: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement.

_____. 2014. “What We’re Talking About When We Talk About the ‘Civic Field’ (And why we should clarify what we mean).” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): Article 8. (http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art8)

Levine, Peter. 2010. “A Map of the Civic Renewal Field.” Blog post: October 25 (http://peterlevine.ws/?p=6024).

_____. 2009. “Collaborative Problem-Solving: The Fake Corporate Version.” Blog post: January 27 (http://peterlevine.ws/?p=5615).

_____. 2014. “Beyond Deliberation: A Strategy for Civic Renewal,” Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 19. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art19

Levine, Peter, Fung, Archon, and John Gastil. 2005. “Future Directions for Public Deliberation.” Journal of Public Deliberation 1: Article 3.

Lippard, L.R., 1984. Get the Message? A Decade of Art for Social Change. E.P. Dutton, New York.

Lukensmeyer, Carolyn. 2014. “Key Challenges Facing the Field of Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): Article 24. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art24

Martin, Isaac William. 2015. “The Fiscal Sociology of Public Consultation.” Pp. 102-124 in Lee, McQuarrie, and Walker (eds.), Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation. New York: NYU Press.

Mathews, David. 2014. “What’s Going on Here? Taking Stock of Citizen-Centered Democracy.” Pp. 4-7 in Connections: Taking Stock of the Civic Arena. Dayton, OH: Kettering Foundation.

McCoy, Martha. 1997. “Art for Democracy’s Sake.” Public Art Review 9: 4-9.

_____. 2014. “The State of the Field in Light of the State of our Democracy: My Democracy Anxiety Closet.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): Article 13. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art13

Medvetz, Thomas. 2008. “Think Tanks as an Emergent Field.” New York: Social Science Research Council.

Mizruchi, Mark S., and Lisa C Fein. 1999. “The Social Construction of Organizational Knowledge: A Study of the Uses of Coercive, Mimetic, and Normative Isomorphism.” Administrative Science Quarterly 44:653-83.

Mutz, Diana. 2008. “Is Deliberative Democracy a Falsifiable Theory?” Annual Review of Political Science 11:521-38.

National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD). 2015. “The Arts at NCDD Events.” Available at: (http://ncdd.org/events/arts).

National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation (NCDD), the International Association for Public Participaction (IAP2), the Co-Intelligence Institute, and others. 2009. “Core Principles for Public Engagement.” (www.ncdd.org/pep/).

NCDD (see National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation).

O’Leary, Rosemary, and Lisa B. Bingham. 2003. The Promise and Performance of Environmental Conflict Resolution. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

One America Advisory Board. 1998. “One America in the 21st Century: Forging a New Future.” Washington, DC. <http://clinton2.nara.gov/Initiatives/OneAmerica/cevent.html>

Polletta, Francesca. 2015a. “How Participatory Democracy Became White: Culture and Organizational Choice.” FIELD 1: 215-254.

Polletta, Francesca. 2015b. “Public Deliberation and Political Contention.” Pp. 222-243 in Lee, McQuarrie, and Walker (eds.), Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation. New York: NYU Press.

Pollock, Venda Louise, and Joanne Sharp. 2012. “Real Participation or the Tyranny of Participatory Practice? Public Art and Community Involvement in the Regeneration of the Raploch, Scotland.” Urban Studies 49:3063-3079.

Powell, Walter W., and Paul J. DiMaggio. 1991. “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields.” Pp. 63-82 in The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, edited by W.W. Powell and P.J. DiMaggio. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reed, T.V. 2005. The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Roy, William G. 2010. Reds, Whites, and Blues: Social Movements, Folk Music, and Race in the United States. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Selznick, Philip. 1949. TVA and the Grassroots: A Study in the Sociology of Formal Organization. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Scheppele, Kim Lane. 2004. “Constitutional Ethnography.” Law and Society Review 38:389-406.

Scully, Patrick L. 2014. “A Path to the Next Form of (Deliberative) Democracy.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): Article 12. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art12

Sirianni, Carmen, and Lewis Friedland. 2001. Civic Innovation in America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Small, Mario Luis. 2011. “How to Conduct a Mixed Methods Study: Recent Trends in a Rapidly Growing Literature.” Annual Review of Sociology 37:57-86.

Snider, J.H. 2010. “Deterring Fake Public Participation.” International Journal of Public Participation 4:90-102.

Soule, Sarah A. 2009. Contention and Corporate Social Responsibility. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stimson, Blake, and Gregory Sholette, eds. 2006. Collectivism After Modernism: Art and Social Imagination after 1945. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Tepper, Steven. 2010. Not Here, Not Now, Not That! Protest over Art and Culture in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tepper, S., Gao, Y., 2008. Engaging art: what counts? In: Tepper, S.J., Ivey, B. (Eds.), Engaging Art: the Next Great Transformation of American Cultural Life. Taylor & Francis Group, New York, pp.17-48.

Thomas, Nancy L., and Matt Leighninger. 2010. “No Better Time: A 2010 Report on Opportunities and Challenges for Deliberative Democracy.” The Deliberative Democracy Consortium and the Democracy Imperative. (www.deliberative-democracy.net).

Thomas, Nancy L. 2014. “Democracy by Design.” Journal of Public Deliberation 10(1): Article 17. Available at: http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol10/iss1/art17

Thompson, Nato. 2012. Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011. Boston: MIT Press.

Voeller, Megan. 2015. “On ‘A Lived Practice’ Symposium, School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Nov. 6-8, 2014.” FIELD 1: 275-280.

Walker, Edward T., Michael McQuarrie, and Caroline W. Lee. 2015. “Rising Participation and Declining Democracy.” Pp. 3-23 in Lee, McQuarrie, and Walker (eds.), Democratizing Inequalities: Dilemmas of the New Public Participation. New York: NYU Press.

Walsh, Katherine Cramer. 2007. Talking about Race: Community Dialogues and the Politics of Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Whelan, James. 2007. “Six Reasons Not to Engage: Compromise, Confrontation and the Commons.” COMM-ORG Papers 13. University of Wisconsin. (http://comm-org.wisc.edu/papers2007/ whelan.htm).

Whittier, Nancy. 2009. The Politics of Child Sexual Abuse: Emotion, Social Movements, and the State. Oxford University Press, New York.

Williams, Mike. 2004. “Discursive democracy and New Labour: Five ways in which decision-makers manage citizen agendas in public participation initiatives.” Sociological Research Online 9.

Wolz, Chris. 2011. “Room for Progress in Online Participation for Open Government.” Blog post: March 16 (http://www.forumone.com/ blogs/post/room-progress-online-participation-open-government-tim-bonnemann-sxswi).

Zacharzewski, Anthony. 2010. “Democracy Pays: How Democratic Engagement Can Cut the Cost of Government.” Brighton, UK: The Democratic Society and Public-i.

Zald, Mayer N., and John D. McCarthy. 1980. “Social Movement Industries: Competition and Cooperation among Movement Organizations.” Research in Social Movements, Conflict, and Change 3:1-20.

Zarek, Corinne, and Justin Herman. 2015. “Announcing the U.S. Public Participation Playbook.” Office of Science and Technology Policy blog: February 3 (https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2015/02/03/announcing-us-public-participation-playbook).