Points de vue: Agency, Contingency, Community, and the Postindustrial Turn

Cynthia Hammond and Shauna Janssen

This essay considers the role of site-responsive, creative methods in enabling “communities of concern” to form around the cultural landscape of a postindustrial urban site in transition in Montreal, Canada. Communities, according to political theorist Chantal Mouffe, are “held together not by a substantive idea of the common good but by a common bond, a public concern … therefore a community [can exist] without a definite shape or a definite identity.”[1] In this essay we ask, how can socially-engaged practices, place-based research, collective action, and creative outcomes be used as methods for generating public dialogue about the urban future of the recent past?[2] We focus on our four-month project of public engagement in a significant, postindustrial district of Montreal: the historic neighbourhood of Griffintown. Like many formerly industrial cities, Montreal is re-imagining its former manufacturing, canal, railway, and working-class districts. The billion-dollar initiative to revitalize Griffintown began in the mid 2000s, after several decades of deliberate depopulation, effected through zoning changes. Starting in 2007, and again in 2010, the neighbourhood was hit with successive waves of demolition and construction. This activity originated in an urban plan remarkably bereft of public amenities, given that the major impetus was to build––and sell––several thousand residential condominiums. The city’s decision to farm out the redevelopment of Griffintown to a developer best known for building mega-malls incurred considerable controversy, particularly because of the lack of public consultation throughout.[3] Despite preservationists, residents, and artists’ forceful critique of the destruction of Griffintown’s historic fabric,[4] the city has continued to neglect local knowledge, collective memory, and user-group/citizenry in its approach to the district and likewise in its more recent efforts to capitalize on the neighbourhood’s heritage.

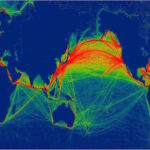

Our project revolved around a key architectural object within Griffintown: the Wellington tower, an icon of Montreal’s industrial zenith. The irregularly-shaped yet elegant modern building was a train switching station from 1943 until its closure in 2000. At the peak of its activities, the tower was a crucial cog in a vast continental network linking the maritime shipping industry and North American railway companies with Montreal’s port and the Lachine Canal. Collectively, the railways, canal, and port formed the largest urban industrial landscape in Canada up until the 1950s, with the tower at its centre. After closing, the Wellington tower sat abandoned, quietly providing shelter to the district’s homeless for over a decade. This was the same decade in which the redevelopment of Griffintown began. It was in this context, with the first condo owners just starting to move in, that the city of Montreal evicted the squatters from the Wellington tower, barricaded the building, and issued a call for proposals for the tower’s retrofit as a “community cultural centre” in autumn 2013.[5]

This call for proposals might appear to be a breath of fresh air in an otherwise troubled atmosphere of negligent urban development practices. Given the much-deplored lack of social amenities in the redevelopment of Griffintown, who could object to the intent to create shared cultural space?

“Points de vue” (points of view) is the name of a collective [6] that emerged in response to the city’s call for proposals. As a group, our training, expertise, and professional practices cover art, art history, museum education, architecture, design, theatre, and performance studies. In autumn 2013 we co-authored a proposal to the city of Montreal.[7] Our brief did not propose, however, a retrofit design for the building; in fact, we did not propose a vision for a community cultural centre at all. Instead, we tabled a proposition that we, as artists, would provide the public consultation that the city otherwise appeared to have forgot. Before any redesign could take place, we argued, some key questions needed to be answered. What can “culture” and “community” mean in a neighbourhood like Griffintown? How might the building serve the future residents of Griffintown as an aperture onto its significant past, as well as be a space for the neighbourhood in the future? For reasons we detail below, we believed that meaningful answers could only be arrived at through multiple points of view. Accordingly, the Points de vue collective envisioned a series of thematic, in situ, “urban laboratories,” each exploring a different aspect of the tower’s history, its heritage, and its surrounding physical, cultural, and biological landscapes. Our goal was to engage as many diverse publics as possible on the question of the tower’s future, while providing information about the past and creating opportunities for local knowledge about the tower and its environs to surface.

The city rejected our proposal. The Points de vue project was soon taken up, however, by the Darling Foundry,[8] an international visual arts centre. The Darling Foundry is also located in Griffintown, in a large postindustrial building, one of the few that remain untouched by gentrification. Reimagined as the gallery’s public summer programming,[9] our urban laboratories elaborated on four core themes emerging from Griffintown’s history, present, and fast-approaching future. These themes emphasized the points of view of different age groups; the point of view of physical accessibility; that of urban archaeology, and that of postindustrial ecology. Whether we were invoking the perspectives of children or those with reduced mobility, whether we invited direct experiential encounters with the vanishing material heritage of the neighbourhood or with its resilient biological diversity, our labs underscored a variety of cultural landscapes in play. We concluded our four-month collaboration with the tower and approximately 100 participants with an exhibition at the Darling Foundry in September 2014, where we also launched a small publication about the project.[10] The purpose of the exhibition was to share our findings with the city of Montreal, with the architects who would be responsible for the retrofit of the building, with the future community-cultural actors responsible for managing the Wellington tower, and with a broader public that is invested in Montreal’s urban future.

In what follows, we introduce the intellectual and physical contexts of our project, paying attention to the politics of deindustrializing Montreal and to the particular case of the Wellington tower. We then summarize how each half-day lab created a sustained (for some participants, cumulative), embodied, and haptic encounter with the tower and its cultural landscapes. We describe how these labs situated our participants within the effects and affects of what we are calling the “postindustrial turn”,[11] by which we mean a neighbourhood’s dramatic turn from deindustrializing urban landscape to residential, consumer-driven design, or “leisurescape.” Our participants could witness, month to month, the rapidity and decisiveness of such a turn for themselves, as the path we would take during one lab would no longer exist a few weeks later. Our essay takes up this collective experience of witnessing in order to explore how Griffintown’s transformation was itself fertile ground for nurturing provisional or temporary “communities of concern.” We also address how such provisional communities are not conflict-free, nor are such collective projects of creation necessarily harmonious from start to finish. We thus begin, and end, with the concepts of partial perspectives and multiple points of view, as principles that guided not just our project in the summer of 2014, but that guide our critical stance more broadly as artists seeking difference and dissent within the city today, on behalf of the city of tomorrow.

Contingency, partial perspectives, points of view

The concepts of spatial contingency, partial perspectives, and multiple points of view were key to our project with the Wellington tower. Working in what was, in essence, an enormous construction site meant embracing large-scale, ongoing contingencies. Collaborating with an unpredictable public (we never knew who would join our labs, or what their responses would be) meant another set of contingencies. Our collective valued both.

Jeremy Till observes that in contingent spatial and social conditions (such as the complete overhaul of a historic neighbourhood) creative action cannot necessarily espouse nor effect an instrumental outcome, such as a “solution.”[12] Till argues, however, that creative actors can exercise choice within such contingencies, and that “we enter into these choices as sentient, knowing, and situated people.”[13] What might “situated” mean in this context? Donna Haraway coined the term “situated knowledge”[14] to explain the value of “partial perspectives,” that is, knowledge that emerges from the particular, embodied place of the individual, or a group of individuals with shared experience. Situated knowledge has a provisional quality to it, in that it comes from “points of view which can never be known in advance.”[15] Haraway is careful not to privilege situated knowledge as superior to professional or, in her case, scientific knowledge, but she does underscore how the embodied or subjective nature of this knowledge has meant that it is viewed with suspicion, and is typically othered and denigrated within authoritative forms of discourse and practice. For this reason it is a frequently under-mobilized source not only in science but also in urban design and revitalization work. There are parallels between what Haraway is describing as a messy form of embodied and partial yet still valuable knowledge, and the kind of building and site that we found at the Wellington tower: a place of dereliction, presumed vacancy, under- instrumentality, and contingency.[16] These ways of thinking about space and knowledge helped us to refuse to characterize a ruined industrial building as an urban problem in need of a solution, and supported our approach to the tower as, instead, a rich resource in its present state, a “witness” of urban change, and a powerful interlocutor for the unpredictable individuals and groups who participated in our project.

The expression “points of view” thus had several senses for us. The Wellington tower inspired the first of these, as it was designed to facilitate multiple views over Montreal’s then-industrial heart, the Peel Basin. The tower’s windows were, at the time our project began, boarded up but they still had the potential to be literal apertures onto a changing urban landscape, while summoning the histories of labour that are disappearing from view throughout the city’s formerly industrial core. The second sense of the phrase was tied to the tower’s cultural landscapes, which are, as of this writing, still mutating. These include: the cultural landscape of labour and industry; the cultural landscape of homelessness and itinerancy; the cultural landscape of ruderal urban ecologies, and the cultural landscape of urban renewal, destructive as this is of the other landscapes. And finally, we saw our project as enacting and enabling different voices and points of view about the encounter with these cultural landscapes. A key means for us to access all these points of view was to walk (or if walking was not possible, roll). In traversing the distance from the Darling Foundry to the Wellington tower, we gave our participants first-hand access to the tower at a moment of intense change.

Griffintown: Site and context

Griffintown is inextricably linked with the history of Montreal’s industrialization, urban development, and deindustrialization. Eighty-four hectares of urban land comprise the district, which is located in Montreal’s southwest borough, and situated adjacent to the Lachine Canal, today a National Historic Park. In the eighteenth century Griffintown was considered to be the city’s first suburb.[17] It formed in tandem with Montreal’s industrial revolution, which attracted immigrants from the United Kingdom, some of whom brought with them technology, science, and capital, and went on to acquire fortunes through the railway, tobacco, and sugar refining industries.[18] In contrast to this small elite, the majority of immigrants arriving in Montreal were poor, uneducated, and Irish Catholic. Griffintown is where many such immigrants settled. The neighbourhood’s industrial growth meant that its residential density was the greatest in Canada in the second half of the nineteenth century. As early as the 1850s, Griffintown had evolved into a burgeoning working class neighbourhood, built alongside the major industrial installations of the time. This 1896 photograph of Griffintown depicts a line of laundry in the middle foreground, perhaps 20 metres from the nearest shipping basin. This proximity communicates what was once the dense configuration of industry, canal, railway, church, and housing.

![[Image 4 - Aerial view showing Griffintown in 2015. Source: Google maps]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/4-IMAGE-4_Griffintown-Map_source_Google.jpg)

![[Image 5 - View of Griffintown, c. 1896, towards the South Shore, showing St Ann’s Church (demolished 1970), the Lachine Canal and the Peel Basins. Source: McCord Museum]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/5-IMAGE-5_View-of-Griffintown-1896.jpg)

Between the 1850s and the end of the nineteenth-century the population of Griffintown increased with another wave of immigrants (as many as 100,000)[19] and the local migration of equally poor and unskilled rural French Canadians. Urban sociologist, Montrealer Herbert Brown Ames (1863-1954), described Griffintown as “the city below the hill,” observing how the working-class immigrants residing in this quarter of the city were segregated morphologically as well as through economic divisions from the middle-class society who lived in the “city on the hill.”[20] Residents lived in deep poverty, in tight compression, but developed closely-knit communities and a strong sense of collective identity.[21]

The morphology of Griffintown changed dramatically throughout the twentieth century. A key factor resulting in the deindustrialization of Griffintown was the closure of the Lachine Canal in 1968. The cultural landscape of Griffintown, however, had already begun to transform with the construction of the Canadian National Railway viaduct in the 1940s and the Bonaventure Expressway in 1965, developments that served to further isolate the neighbourhood from Montreal’s downtown core and the Old Port district to the east. The expressway was the more damaging of the two changes, however, as it literally severed the neighbourhood in two. A wave of construction of transportation infrastructure coincided with the city’s embrace of utopian urbanism [22] and modernist planning initiatives, many in preparation for the 1967 world’s fair, Expo 67. Although Griffintown was located squarely in the middle of the effects of this modernizing and utopian turn, the impoverished neighbourhood remained peripheral in every way to Montreal’s drive to reimagine itself as a cosmopolitan, postindustrial wonderland in 1967.

The Wellington tower, at the crossroads then and now

Griffintown, and thus the Wellington tower, stand literally at the crossroads between four distinct neighbourhoods: Vieux-Montréal to the east, Ville Marie to the north, Petite-Bourgogne to the west and Pointe-Saint-Charles to the south. Petite-Bourgogne and Pointe-Saint-Charles share in the working-class heritage of Griffintown and the Wellington tower, as both neighbourhoods developed in relation to the availability of work alongside the industrial canal, while Vieux-Montreal and Ville Marie today belong more to a moment of postindustrial prosperity.[23] All four districts have seen gentrification and transformation of their built environments, primarily through new-build, residential space, but this phenomenon is more pronounced in what were, formerly, fairly homogenous, working-class neighbourhoods. In Petite-Bourgogne and Pointe-Saint-Charles, for example, owner-occupiers live next door to long-term renters, some of whom have family histories of working in the railway and canal industries dating back multiple generations.[24] For such established residents, the Wellington tower is a significant icon of an era when skilled labourers were numerous and when Montreal was just relinquishing its crown as Canada’s most powerful industrial city. There is still a wealth of living memory of the tail end of this period: the second World War and the fifteen years following the war.[25] This is precisely the period in which the Wellington tower was built.

![[Image 6 - Interior of the Wellington tower, showing switchman and technicians at console, c. 1948. Source: Musée canadien des sciences et technologies]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/6-IMAGE-6_Interior-of-Wellington-tower-showing-switchman.jpg)

The Wellington tower integrated highly advanced technology and electrical switching systems. These systems efficiently managed the physical matter of railways, trains, an enormous swing bridge (now locked) and lift bridge (now gone). The building is of considerable heritage value in terms of its unusual form, concrete construction, and modernist architectural language. It also summons an era of specialized labour; many of the jobs associated with this tower, such as switchman, signalman, movement director, and bridgeman, live on in memory only.

![[Image 7 - The swing and lift bridges, Peel Basin, Griffintown, 1943. The Wellington tower is visible at left behind the swing bridge. Source: Archives nationales du Canada, PA202868]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/7-IMAGE-7_The-Swing-and-Lift-Bridges-e1457715550260.jpg)

“A sparkling sense of community”? Griffintown’s uneven redevelopment

The move to transform the tower into a community cultural centre can be seen as part of a larger trend of top-down creative industries, cultural incubators, and social innovation-style projects.[26] The language used to describe these initiatives tends to gloss over the idea of “community”, while art or “creativity” tends to be harnessed, uncritically, to Creative City aspirations.[27] While “heritage” is certainly invoked––belatedly––by Griffintown’s developers, the reality is that those same developers have destroyed most of the neighbourhood’s physical, built heritage, and much of its intangible heritage. The sector is literally unrecognizable from five years ago. Janssen observed in 2014 that at that time “it was increasingly difficult to discern between the ruins of deindustrialization, what was being rebuilt, and what was being ruined as a direct cause of Griffintown’s revitalization.”[28]

Griffintown’s proximity to water (the canal) and the central business district have been key factors in the speed and heavy-handedness of its redevelopment. Construction has proceeded swiftly, but has been dogged by controversy. Numerous low-rise nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings have been razed and are being replaced with 10-15 storey residential towers, indistinguishable from banal developments elsewhere on the island of Montreal. The original number of subsidized housing units (935) has been cut by 51%, and lumped together in a poverty pocket out of sight of the canal.[29] Critics observed how the provision of public amenities, such as schools, green spaces, and health-care services did not appear to have been among the city or the developer’s goals.[30] Less frequently mentioned were the needs and rights of the long-term residents of the district, many of whom are, or were, homeless, transient, or economically marginal. These individuals are being squeezed into ever smaller and more precarious corners of what has become an epic building site. In contrast, the billboards advertising the new condos suggest that thousands of new units have been designed exclusively for upwardly-mobile, able-bodied, heterosexual couples (mostly white) in their early twenties.

![[Image 8 - Billboard advertising “District Griffin” condominiums, 2011. Photo: S. Janssen]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/8-IMAGE-8_Billboard-advertising-District-Griffin_2011_SJanssen.jpg)

![[Image 9 - Contingent shelter approximately 150m from the Wellington tower, 2014. Note the new colour panels lauding the district’s industrial past. Photo: C. Hammond]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/9-IMAGE-9_Contingent-shelter_2014_CHammond.jpeg)

The city has celebrated Griffintown’s current revitalization as the largest building project in Montreal’s urban development since Expo 67.[31] Yet the contrast between poverty and excess intensifies with the completion of each new residential tower. Griffintown’s first upscale, boutique hotel opened during the same summer that we undertook Points de vue, within a few hundred feet from the tower’s boarded up windows and graffitied surfaces. During one of our preparatory walks on a sunny Saturday in July 2014, we saw a bride in a $10,000 dress sweeping towards the tower from rue Peel. A wedding photographer, with an entourage of several well-tanned men in tuxedos, scampered after her on the bicycle track that runs adjacent to the Lachine Canal. Just before she reached the Wellington tower, the bride posed against the backdrop of a tiny vegetable garden that an itinerant community has planted, illegally, on the ramparts of the Canadian National railway tracks, for food.

![[Image 10 - The bicycle track in front of the Wellington tower (visible at right), July 2014. Photo: C. Hammond]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-10_Wedding-couple-on-bike-path-next-to-tower_2014_CHammond.jpeg)

![[Image 11 - Alt Hotel in background; District Griffin sales pavilion in foreground, 2015. Photo: C. Hammond]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-11_Alt-Hotel_2015_CHammond.jpg)

The city and the developers have lauded Griffintown’s urban renewal from the outset as a crusading force for good, revitalizing “dead” and “wasted”[32] urban space, and bringing order and public safety to the district. In the words of developer Le Canal, “Yesteryear’s rundown neighbourhood is gone. Today, Griffintown is synonymous with an eclectic mix of residents, a sparkling sense of community, and a taste for the good things in life.”[33] Griffintown has even been touted as Canada’s “next great neighbourhood.”[34]

The discourse on Griffintown as a previously blighted, even dangerous urban site, socially and culturally disinvested, laid the groundwork for the market-driven revitalization and served in turn to justify the lack of public consultation. Tropes such as revitalization and rehabilitation position profit-driven development as the fast lane to better urban futures, as an unimpeachable source for the life of the city itself. What this powerful discourse obscures, but does not entirely eradicate, are smaller, interstitial, cumulative urban dynamisms, such as postindustrial ecologies, and the intensely creative, socio-spatial survival strategies of less visible, under-resourced urban agents. The politics of space are particularly acute in this part of Montreal at this time. Griffintown is thus a powerful site for artistic engagement in and with those politics.[35]

![[Image 12 - Points de vue’s urban lab #2: Participants seated on the grass adjacent to the Wellington tower. Photo: C. Bédard]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-12_Points-de-vue-lab-2_2014_CBédard.jpeg)

Griffintown and “cultural activism”

The authors of the present text have had a critical and creative relationship with the spaces and politics of Griffintown since 2010.[36] In that year, Janssen created Urban Occupations Urbaines, a curatorial platform for bringing artists into the neighbourhood to work critically and creativity with Griffintown’s spatial histories and fast-changing urban fabric. In her call for proposals, she emphasized that artists would need to engage with the neighbourhood’s then-threatened cultural heritage, its architecture, and morphology.[37] Janssen asked the selected artists to reflect on the enactment of private interests in what were, then, “public”, under-instrumentalized, and interstitial spaces in the neighbourhood. The artists then created site-responsive projects via specific themes such as: consumerism; green space as fragile public amenity; local myths and histories of crime, gender, and class; the cultural fertility of postindustrial landscapes, and representations of collective memory. Throughout, Janssen developed relationships with a variety of stakeholders and cultural actors concerned with what was, then, the start of Griffintown’s renewal. Part of her method was to conduct extensive oral histories with long-term residents, whether these were squatters, renters, or property owners, likewise with artists and newly arrived cultural workers.[38] Thus by the time we created Points de vue, core members of our collective had had three years of close engagement with Griffintown, working in the tradition of intervention via the intersection of art and cultural activism.[39]

Urban Occupations Urbaines and Points de vue’s cultural activism are not isolated instances of resistance to urban injustice in this part of Montreal. They belong, rather, to a sustained history of community action and self-determination in Griffintown and other de-industrializing neighbourhoods in Montreal’s South-West, which have focused less on art production and more on urgent social needs such as the right to housing, safe streets, access to education, food, self-government, workers’ rights, women’s rights, and anti-racism movements.[40] However, artists have also organized in Griffintown in particular, as the redevelopment project directly threatened, and then destroyed, many artists’ studios.[41] These forms of action continue throughout the South-West in response to gentrification and are, as is Points de vue, part of a deep history of collective resistance to uneven forms of urban development.

The urban laboratories

While we considered interviews as a method for facilitating public consultation, in the end we chose to work in a way that drew upon our collective skills as artists, theatre professionals, architects, curators, educators, and social historians of the built environment. Our method was hands-on. We designed each lab principally around four different walking routes between the Darling Foundry and the Wellington tower. The Wellington tower and its surrounding cultural landscape were the key interlocutors in our labs; they became active partners in the creative and social work of realizing each of these events.[42]

Lab #1 – Les Jeunes/Youth: a treasure hunt for the Wellington tower

Les Jeunes/Youth was Points de vue’s first urban laboratory, held on 28 June 2014. Curators Camille Bédard, Noémie Despland-Lichtert, and Chantale Potié[43] devised a post-industrial treasure hunt to orient children between the ages of four and twelve to the cultural landscape surrounding the Wellington tower, and to re-imagine the tower not as evidence of urban blight but rather as a treasure to be found. Co-curator Potié describes the afternoon:

The team provided families with a hand-drawn map marked with architectural clues. These led participants from the Darling Foundry towards an enigmatic treasure––the Wellington Tower. The young participants were engaged with way-finding activities, drawing, origami, and creative mapping to traverse and experience the neighbourhood. They were invited to observe their environment and to note their journey in a handmade notebook, separated into four categories: construction, flora and fauna, landscape, and moments. At a mid-way activity stop near the Lachine Canal the children drew a future of their own devising for the neighbourhood. These drawings were then folded into paper boats, brought to a small pier on the Lachine Canal, and launched into the water as an ephemeral trace of the event. Upon arriving at the tower, the children created maps of their journey, referencing the things they saw, remembered, and enjoyed most about their treasure hunt.[44]

![[Image 13 - Still from “Pathways” (Thomas Strickland, videographer and editor), 2014]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-13_Still-from-PDV-video.jpg)

As Griffintown does not at present have a school or any cultural destinations primarily directed at children, we felt that an urban lab that privileged the experience, responses, and pleasures of young people would be an important launch for our efforts to engage with perspectives not usually heard or seen in the neighbourhood. Our small but enthusiastic group of children and parents consented to being filmed on their walk; this film [45] and ephemera from the lab became the content for this aspect of our exhibition. In the children’s collective vision, Griffintown became a dreamscape; not a dream of condo towers, market prices, and boutiques, but rather a place of seeking, finding, and envisioning.

Lab #2 – Spatial justice: public space and accessibility

In this lab, curators Marie-France Daigneault-Bouchard, Shauna Janssen, and Thomas Strickland asked: who has access to the swiftly-changing built environment of Griffintown and the Lachine Canal district? The district’s transformation into an enormous chantier (construction site) has diminished the safety of the streets, as it has shrunk the quantity of public and un-programmed space. On a sunny 26th of July, 2014, our participants found that one must be fit and young to dodge the piles of rubble, navigate the heavy machinery and missing sidewalks, and tolerate the daily reverberations of pile-drivers pounding into bedrock. Using this chaos as a shared experience and basis for reflection, we invited participants to explore the question of accessibility in the built environment by thinking about visible and invisible disabilities, the gendering of space, economic displacement, and exclusion by class.[46] We gave each participant a spatial justice emblem, designed in solidarity with logos created by human rights groups.

![[Image 14 - Spatial justice emblem: acrylic on wooden panel, colour photographs. Design: Shauna Janssen and Thomas Strickland; fabrication: Cynthia Hammond and Thomas Strickland]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-14_Spatial-Justice-emblems.jpg)

As participants wove their way along the precarious route between the Darling Foundry and the Wellington tower, we asked them to identify and mark moments of what they considered to be spatial injustice. This directive resulted in the discovery of diverse instances of inaccessibility and injustice, including physical constraints for all those who are not normatively mobile, the auditory and olfactory barrages of a construction site, and the more subtle visual obstructions that slip into social barriers, such as the planters lining the sidewalk in front of a new upscale cafe, just a few meters from a homeless squat, or a homophobic statement scrawled across a wall. Participants placed their spatial justice emblems in specific locations of their choosing along our route and documented these gestures. Of the many photographs taken, the curators chose sixteen images for the exhibition. These pictures collectively mapped spatial injustice in the cultural landscape of the Wellington tower. The images were a reminder to those who would redesign the tower that it would need to be attentive to a diversity of future users, not just to the young, athletic bodies pictured throughout the neighbourhood on advertising and hoarding walls.

![[Image 15 - Participants traversing Griffintown during the Spatial justice urban lab, 26 July 2014. Photo: C.Bédard]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-15_Urban-lab-2_CBédard.jpg)

![[Image 17 - Spatial justice urban lab outcomes, as shown in the exhibition at the Darling Foundry, September 2014. Photo: Mathieu Gagnon]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-17_Spatial-justice-in-PDV-exhibition.jpg)

Lab #3 – Archiving urban change: the social agencies of material culture (23 August 2014)

Our aim with the third lab, “Archiving Urban Change” was to create a hands-on, haptic, and archaeological exploration of a neighbourhood in transition. Curators Marie-France Daigneault-Bouchard, Shauna Janssen, and Thomas Strickland invited participants into an embodied, collective work of witnessing, archiving, and gathering the material culture of urban change. In brief, we built an archive in an afternoon. And we asked: what can this archive tell us about the past, present, and future of the Wellington tower, its environs, and the transformation of both? We provided participants with tools to collect and record the traces of a specific moment in urban time and space. In teams, we explored overgrown parking lots, neglected parks, abandoned interstitial spaces, condo sales pavilions, and living space, both formal or informal. Some chose to take field notes, some photographed the findings, while others took on the role of urban explorer. Participants gripped the spirit of their roles with gusto, collecting pieces of danger tape, bricks, broken tiles, water samples from a dumpster, a feather, sunglasses, a rusty street sign, broken glass, interior decorating fabric samples, and a single playing card, among other objects.

We delighted in seeing the participants embrace their work of finding significant or telling artifacts along the four itineraries we had mapped from the Darling Foundry to the Wellington tower. They easily made the shift from pedestrians avoiding garbage on the street to intrepid explorers collecting specimens with intelligence and humour. The activity concluded in a gathering by the Wellington tower, where we laid out all the findings on a white tarp. Fortified with juice and water, the participants then were invited to write individual reflections about an object of their choosing. We asked them to consider whether their object spoke to the past, present, or future of the neighbourhood. In her text, one respondent dwelt upon a collection of small stone fragments:

The building from which these stones originated was created in the past. [But] I believe this building reflects both past and present because, despite its dilapidated state, it is still standing; it is part of the present environment, although its future is uncertain. I certainly hope it will not be torn down to make space for something new. I would rather they renovate it. These pieces of concrete and asphalt evoke solitude and nostalgia. They ask for our help.[47]

Another participant wrote,

This object (architectural, decorative fragment) of the present recalls the past through its shape and its dusty state. It is also linked to the future by its questioning of the site’s future and its architecture––the city’s transformation. The history of this object is linked to the transformation of the site, something that cannot be avoided. It recalls the demolition of the older buildings in this neighbourhood. The dust that covers it evokes a lunar, lifeless space.[48]

![[Image 18 - Archiving Urban Change reflection text written by Renata Ribiero, 23 August 2014]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-18-Isabelle-Pichet-arching-urban-change-text.jpg)

![[Image 19 - Archiving Urban Change reflection text written by Isabelle Pichet, 23 August 2014]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-19-Renata-Ribiero-archiving-urban-change-text.jpg)

What the above reflections illuminate about the participants’ experience in this lab are how these kinds of spatially situated encounters with the material culture of urban change allow for the surfacing of affective and emotional connections to a given place. This lab afforded our participants time and space to share and act within Griffintown’s shifting landscape, to literally handle the “details” and sometimes “ordinary affects”[49] of urban change, and to see, hear, and feel the city at a moment of dramatic transformation. Here, the cultural agency of the built environment also looms large, in that the mutation of this landscape was acting in turn upon our participants and, in some sense, radicalizing their experience of a place undergoing unchecked, controversial development. As Grant H. Kester explains, some of the “most meaningful engagement with the pressures exerted by capitalism occurs precisely through our daily experience at the intersubjective and even haptic level.”[50] This and the other Points de vue labs intensified such daily experience by building the participants’ capacity to notice, to engage, and to reflect, together. The mood by the end of the workshop had shifted from gleeful urban discovery to a deeply personal, embodied quietude, but this reflective space was shared in the company of others who had the same experience in common. Perhaps the most meaningful aspect of this lab, for us, was that when our activities concluded, the participants did not want to leave. They wanted to stay near the tower, together.

![[Image 20 - Participant collecting artifacts in the Archiving urban change lab, 23 August 2014. Photo: C. Hammond]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-20_Archiving-urban-change-lab-3_CHammond.jpg)

![[Image 21 - Participants in the Archiving urban change lab seated next to their artifacts and writing reflections, with the tower in the background, 23 August 2014. Photo: S. Janssen]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-21_urban-greening-lab-4-with-R.-Latour_SJanssen.jpeg)

Lab #4 – Urban greening – mapping urban biodiversity

Our run of luck with bright, sunny days ended abruptly with our final urban lab, which took place on a dark and rainy 13 September 2014. Noémie Despland-Lichtert curated the “verdissement urbain” (urban greening) lab, which was designed to bring participants into a close encounter with the postindustrial ecologies of Griffintown. There is increasing interest in the question of “ruderal” landscapes, that is, pockets of urban biodiversity that have flourished in the so-called wastelands left behind by human, often industrial, activity.[51] In a neighbourhood in development, such landscapes are at great risk. To bring this aspect of Griffintown into relief, our team approached local urban naturalist, Roger Latour, to facilitate. Latour is an expert in urban biodiversity and self-seeded urban landscapes.[52] He led enthusiastic participants from the Darling Foundry to the Wellington tower and back, on a winding tour of discovery of Griffintown’s ecologies.

![[Image 22 - Participants with urban naturalist Roger Latour during the Urban greening lab, 13 September 2014. Photo: S. Janssen]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-22_Archiving-urban-change-urban-lab-3_SJanssen.jpg)

Parking lots, cracks in the sidewalks, and abandoned lots revealed how the neighbourhood’s location alongside a canal and an active railway track had resulted in a wonderful variety of plants. Despite the wet weather, participants collected end of season specimens, including prairie grains (various types of wheat and grasses), herbs (plantain, catnip), flowering plants (goldenrod, Lady’s thumb, toadflax, and clover), and food (dandelion, Riverbank grape). We had expected the participants to only take small samples of the plants they found interesting. However, inspired by their discoveries, they took ever larger samples of the early autumn plants. The sense of precarity was acute, not because our participants were busily chopping away at the early fall growth, but because caution tape, orange plastic cones, and notices informing the public of imminent construction showed us, with great immediacy, that these spaces and plants were not going to be flourishing for much longer. The participants knew that the specimens they took would be part of our exhibit later that month.[53]

![[Image 23 - A milkweed bud found on the Urban greening lab, 13 September 2014. Photo: S. Janssen]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/IMAGE-23_milkweed-bud-from-lab-4_SJanssen.jpeg)

![[Image 24 - Jessie Hart leads the drawing phase of the Urban greening lab, 13 September 2014. Photo: S. Janssen]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Copy-of-IMAGE-24-Jessica-Hart-leads-drawing-phase-of-urban-greening-lab_SJanssen.jpeg)

After our tour concluded, once again at the tower, we returned as a group to the Darling Foundry to get warm, drink hot chocolate, dry our specimens, draw them, and press them in anticipation of their presentation at the gallery in less than two weeks. As part of this phase of the lab, artist Jessie Hart [54] guided the participants (many of whom had no prior drawing experience) in the rudiments of botanical illustration. As participants had already been encouraged to select plants from aesthetic choice and in response to what they had learned from Latour, we found that there was no hesitation in shifting to the next step in the process: representation. Again, our expectations were exceeded in terms of how long our participants stayed, and what they contributed. The lab was a joyful, convivial conclusion to our four afternoons in Griffintown.

![[Image 25 - Points de vue, view of the exhibition at the Darling Foundry, 24-28 September 2014. Photo: M. Gagnon]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Copy-of-IMAGE-25_Points-de-vue-exhibition_MGagnon.jpg)

![[Image 26 - Points de vue, view of the exhibition at the Darling Foundry, 24-28 September 2014. Photo: M. Gagnon]](https://field-journal.com/stagejanV2/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Copy-of-IMAGE-26_Points-de-vue-exhibition_MGagnon.jpg)

We had ten days to translate all the outcomes of the urban laboratories into a coherent exhibition that would communicate effectively to a diverse public, while representing a diverse set of participants and intentions. In the case of the third lab, “Archiving urban change”, all participants’ “points of view” were represented in the gallery display, via the artifacts they collected and the written responses we received. In other cases, some curatorial selection was necessary, such as with the “Spatial justice” lab, which relied on photographs taken by participants. Some images were better framed than others and some were out of focus. When it came to representing “Les jeunes/Youth” our team decided that video was our preferred method to communicate the spirit and findings of the lab. The video was suggestive rather than documentary, and so is itself a partial perspective on the events that day. And in the case of the “Urban greening” lab we collaborated on the creation of our display with our two experts, Latour and Hart, who worked with the core curatorial team [55] to make a generous and representative selection for the display. In addition, the participants in each lab were named on didactic panels that explained the purpose of the workshop, in French and in English.[56]

Towards an inclusive urban future: “culture” and “community”

To return to a question we posed at the very beginning of our process in 2013: what do ‘culture’ and ‘community’ mean in a neighbourhood like Griffintown? As this essay has demonstrated, the words ‘community’ and ‘culture’ are more complex, ambiguous, and even more exclusive terms than they might initially appear, if they are taken in context. Various scholars have informed our position on the notion of ‘community’ as something that develops around issues or sites of shared concern, rather than emerging out of consensus or some idea of essential similarity.[57] For art historian Miwon Kwon, the “instability of identity and subjectivity can be the most productive source of such explorations” in community-based art projects.[58] Kwon also imagines collaborative and community-based art projects as both a coming-together and unraveling-of collective social processes.[59] As it pertains to community-specific art projects, Kwon suggests that the “unstable and inoperative” nature of community can create alternative models of collaboration, spatial, and social belongings.[60]

Following Mouffe and Kwon, we saw the labs as spaces for developing temporary communities in which it would be possible to build shared concern for the Wellington tower’s history and its future purpose, but also for the larger context of Griffintown itself. What our participants consented to was joining our collective on the journey––literally on the walk––to the tower, its past, present, and potential futures. Together, with and through our differences, we witnessed a specific moment in time in the transformation of Griffintown. Our labs were thus points of transfer and dialogue, as well as points of view,[61] and built, in a sense, spaces that were public, for temporary social encounters as well as collective discovery.

Urban space generally and neighbourhoods particularly are sites of contestation, where divergent spatial politics and power relations are negotiated. When urban revitalization projects fail to include meaningful public consultation, the effects are manifold, including the destruction of significant parts of the built environment and erasure of the material locus of living memories. Other, interstitial histories are also at stake, as development frequently targets postindustrial spaces that are home to marginal city dwellers, such as the homeless, artists, the under-employed, and the transient, who are often displaced as a result of these so-called revitalizations. In Griffintown’s shift from industrial urban zone to postindustrial leisurescape, there has been a deep disconnect between the human (and non-human) agents who live in and use these spaces on a daily basis and those who hold the most power to transform the neighbourhood.

One of our aims with Points de vue was to foreground these forms of human, non-human, and spatial agency. We did this by collecting the visual and textual accounts of important, first-hand encounters with changing urban landscape. Normally urban assessment is delayed until the moment of a building or urban plan’s completion. An innovation of our project was to not simply insist on a form of public consultation, but also to privilege the material, visual, and textual traces of that consultation. As described above, our exhibition included hundreds of objects, specimens, images, and one video from our process. Thus our process and results made visible the fact that the Wellington tower, even in its ruined and abandoned state, was important, like-wise the social and biological life that surrounded that building.

As mentioned above, we saw the Wellington tower in its post-industrial state as a witness of sorts to the transformation of its surrounding cultural landscape. And more significantly, we believe that our labs afforded our participants an encounter with the city that was transformative, that (temporarily) transformed their experience of the city and their perceptions of urban renewal. In our view, the labs themselves were a series of micro apertures or openings that made it possible for our participants to indulge their curiosity about the future of the tower by taking part in the making of collective spatial encounters that allowed for multiple and critical points of view to surface, and for our participants to take part in witnessing up close the materials, biodiversity, and spaces that are produced by urban change.

Conclusion: conflict, enchantment, and the making of public space

It would be easy, given all the actors, events, and outcomes to simply illustrate a positive portrait of what happened with Points de vue.[62] Our collectively-planned and carefully executed series of events over the course of a year meant that we got what we sought: multiple points of view about the tower and its possible futures, and for that matter, multiple points of view about our project, strategies, and outcomes. But inherent to such multiplicity is conflict and dissent; our project was dogged by practical, logistical, and interpersonal power dynamics and problems. We encountered a number of challenges and contests to the power that we had taken, without asking anyone’s permission, to enter into the charged discourse about Griffintown’s redevelopment in general, and the future of the Wellington tower in particular.

We experienced insider-outsider dynamics emerging within our relatively small groups, when occasionally, among our participants, a resident of an adjacent neighbourhood (never Griffintown) asked what right we and the other participants had to be engaging in this sort of work; in other words, if we didn’t live near Griffintown, how could we have a say? Midway through the summer we experienced another form of this sort of territorialism when we received pressure from some of the official competition finalists to cease our labs. In a series of emails, one member of a finalist team told us that our work might dilute or distract from the sanctioned redesign activities. (We explained that we were working with the Darling Foundry and did not need approval for our labs; that we looked forward to sharing the results with all finalists, and invited the individual in question to participate in the labs herself. She declined.) We saw some finalists attempt to colonize our public events, and use them to gauge this or that intention for the tower, a backhanded form of public consultation (we resisted).[63]

We also saw issues of authorship arise, within our team and with our participants. Despite using standard image and participation consent forms, which outlined the intent to incorporate outcomes from the labs in our final exhibition, two participants raised doubts towards the end of the summer about the ethics of “using” the participants’ creative labour for the purpose of our team’s exhibit. One solution we came up with was to give one of these participants space for her own work in the exhibit, but we remain unsure of the success of this decision, as the work was not directly connected to the goals of Points de vue, and it had little connection to the Wellington tower itself. And we discovered subsequently that another participant had attempted to claim our work as hers in conversations with other cultural actors, by virtue of the fact that she had attended all labs.

Interpersonal dynamics with our participants were compounded by questions of ethics and attribution, both during the labs and following their conclusion. We were troubled at times by how to share credit while remaining equitable in the identification of relative effort. Not everyone who worked on Points de vue as a core curator did as much work as others, yet we shared credit consistently throughout the process. And while we agreed, as a group, to always identify all collaborators in any public presentations and publications about Points de vue, no matter the differences in workload or contribution, there have been instances when hardly any of the core team were credited in public discussions of the project.[64]

Money and remuneration were also at issue. While everyone who participated as an organizer or curator was paid a stipend, we struggled with the fact that no-one was paid a fair hourly wage for the time they put into their part of our project. The many problems of free or near-free labour in the art world are well-known to us, and the particularly gendered dynamic of women working in the arts for very little money is not one we wished to uphold. Yet in practical terms, we did uphold it, despite the majority of our funding going to the stipends of our team, because the majority of our collective were under-employed women. And relatedly, we were at times dispirited by the lack of communication or practical support from our partnering institutions, and at others inspired by the arrival of unexpected allies and funds.[65]

So why do it? We believe that art is never a solution to social and economic urban problems, but rather a means to make those problems visible, palpable, and bring them into a wider cultural discourse, to the attention of different constituents, or to those with official, decision-making powers. It was very important to us that art and culture not be relegated, in the retrofit of the Wellington tower, to some simpering colour-block panels celebrating the sweat of long-dead labourers, nor to some high-tech gambit that would have nothing to do with the context and affect of the tower, and everything to do with culture as entertainment. And equally, through our work as artists with Points de vue we imagined a “right to the city”[66] that isn’t necessarily predicated on consensus, or certain prescribed modes of collectivity, encounter, participation, and community engagement. Rather, the social and creative dynamics that surfaced and were produced by Points de vue are more closely aligned with what Mouffe refers to as agonistic approaches to critical art practices.

Mouffe posits that artists and artistic urban interventions can play a role in contesting “visions of public space as terrain where consensus can emerge”[67] and support “dissensus that makes visible what the dominant consensus tends to obscure and obliterate.”[68] Following Mouffe, we believe that the city is not a passive entity waiting for the seminal, creative move of the artist to bring it to life (the risky counterpart to the dreadful discourse on urban revitalization mentioned above), or to make it more democratic. Nor should our practice be mistaken for a salve that city officials might rub upon socio-spatial conflicts. Conflict is part of working in the way that we chose to develop the Points de vue project. If one could say that a “community of concern” formed around the Wellington tower through collaborative acts of witnessing and engaging with the phenomenon of a postindustrial turn, then, as artists, we would be the first to acknowledge that this community was conflicted, uncertain, resistant, occasionally bored, as well as being enchanted,[69] engaged, and entangled in what we had collectively discovered, what we shared, and what we made public. And that contingency, uncertainty, heterogeneity, and enchantment are precisely what we feel a space for multiple points of view should be: a city. To end this essay, we offer a translation of a commentary on our exhibition in September 2014:

Bravo on this work for space, over which we never sufficiently concern ourselves, in my opinion. This is a neighborhood that has a great need of activism, considering the vandalism of the monster promoters! It’s important that you interpellated the community over these spaces and this heritage for the purpose of remembering a common history. It would seem that only the past can be the guarantee of a good future. Don’t stop this work! I’d love to collaborate with you sometime.[70]

Cynthia Hammond graduated from Concordia University’s interdisciplinary doctoral program in 2002. From 2004-06, she held the first, federally-funded postdoctoral fellowship at the School of Architecture, McGill University. Hammond teaches interdisciplinary practice and method, architectural history, and studios and seminars on spatial theory at Concordia, where she is presently Chair of the Department of Art History. Her publications explore gender, public history, and questions of heritage in relation to the built environment. Cynthia also has an ongoing exhibition record as a painter, and as a socially-engaged public artist. In her pedagogy, research, and creative work, Cynthia foregrounds the city as her collaborator in mobilizing multiple publics around the politics of urban change. http://cynthiahammond.org

Shauna Janssen is a Montreal-based urban curator, founder of Urban Occupations Urbaines, and a founding member of Points de vue. Her curatorial work involves long-term, documentary, site-specific research projects that collaborate with contested urban spaces. Her ongoing research addresses the cultural politics and futures of postindustrial cities. Janssen has worked for theatre companies around the world for over two decades, and in 2014 earned her PhD in interdisciplinary studies from Concordia University. She has coordinated city-wide creative events, such as Encuentro 2014, and in 2015 was artist-in-residence at the Center for Art and Urbanistics / Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik, Berlin. http://shaunajanssen.ca

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in the Points de vue urban laboratories, as well as Concordia University and the Darling Foundry for financial support of our project. Special thanks to Micheline Chevrier for translation and assistance throughout the Points de vue project, and to Noni Brynjolson for encouraging and facilitating our contribution to FIELD.

Notes

[1] Chantal Mouffe, “Democratic Citizenship and the Political Community,” in The Return of the Political (London: Verso, 2005) 67.

[2] We are borrowing mindfully here from the title of Reyner Banham’s 1976 book, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past (Harper & Row).

[3] Madeleine Cummings, “Griffintown expansions sparks controversy,” The McGill Daily, 12 September 2011 (web) http://www.mcgilldaily.com/2011/09/griffintown-expansion-sparks-controversy/.

[4] Aditi Ohri, “Funeral for a faubourg,” The McGill Daily, 22 September 2008 (web) http:// www.mcgilldaily.com/2008/09/funeral_for_a_faubourg/. Since the mid 2000s, numerous ad-hoc initiatives emerged in response to the city’s plans to revitalize Griffintown. The “Committee for the Sustainable Redevelopment of Griffintown” has been tracking the redevelopment online: http://www.griffintown.org. Other useful online sources that speak to a history of activism in Montreal’s South-West include the websites of the Carrefour d’education populaire, the Atwater Library, Action-Gardien, and the Clinique communautaire de Pointe-Saint-Charles. Facebook has seen an increase in the informal archiving of the visual culture of both industrial urbanism and the surviving social networks of these historic neighbourhoods; some of these groups are actively working to preserve working-class heritage. See, for example, “Griffintown Memories,” “The Real Pointe-Saint-Charles,” and “La Fondation du Horse Palace de Griffintown,” all on Facebook.

[5] “Transformation de la tour d’aiguillage Wellington,” 9 December 2015 (web) http:// www.ville.montreal.qc.ca/culture/transformation-de-la-tour-daiguillage-wellington.

[6] For more information, see “About,” Points de vue, 2014 (web), www.pointsdevuemtl@wordpress.com.

[7] See Points de vue: Tour d’aiguillage Wellington (Montreal, 2013), 20pp (available online) The proposal’s co-authors were Erika Ashley Couto, Marie-France Daigneault-Bouchard, Cynthia Hammond, Shauna Janssen, and Chantale Potié. Noémie Despland-Lichtert, Adeline Paradis-Hautcoeur, and Pascal Robitaille translated the original English into French. Couto, Paradis-Hautcoeur, and Robitaille subsequently left the group to pursue other interests, while Camille Bédard and Thomas Strickland joined the team in summer 2014.

[8] See Quartier Éphémère, “Mandate,” Darling Foundry/Fonderie Darling, 2013 (web) http:// fonderiedarling.org/en/mandate.html.

[9] In this form, the project took the name, “Points de vue: People, Places, and the Spatial Politics of Urban Change.” See http://fonderiedarling.org/en/Points-de-vue-exposition.html.

[10] The exhibition ran for five days, September 24-28, 2014.

[11] The phenomenon by which formerly industrial landscapes are turned into leisurescapes is part of what we are calling the postindustrial turn. To this we would add the wave of interest in deindustrialization, and direct forms of engagement with the heterogeneous historical processes attached to deindustrialization in different places. These forms of engagement include oral history, art, scholarly research, urban exploration, and what has been called “ruin-gazing” or “ruin porn.” See, for example, Steven High, “Brownfield Public History: Arts and Heritage in the Aftermath of Deindustrialization,” in The Oxford Handbook of Public History, James Gardner and Paula Hamilton, eds. (New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2015) and Tim Strangleman, “‘Smokestack Nostalgia,’ ‘Ruin Porn’ or Working-Class Obituary: The Role and Meaning of Deindustrial Representation,” International Labor and Working-Class History, special issue, “Crumbling Cultures,” 84 (2013): 23-37. As fast as cities race to transform and capitalize upon the built traces of the industrial era through redevelopment and “revitalization”, heritage activists, artists, and other observers/actors are increasingly engaged with trying to understand, document, and preserve those traces, or part, before they are completely consumed and drained of their historical weight. North American cities such as Sudbury, Hamilton, Windsor, Philadelphia and many others engage in practices of “forced forgetting” when they strip from the deindustrializing city the evidence of fiscal failure––empty and ruined buildings. See Steven High, “Beyond Aesthetics: Visibility and Invisibility in the Aftermath of Deindustrialization,” International Labor and Working Class History 84 (Fall 2013): 140-153.

[12] Jeremy Till, Architecture Depends (London: The MIT Press, 2009), 55.

[13] Ibid., 59.

[14] Donna, Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and Privilege of Partial Perspective” Feminist Studies 14.3 (Autumn, 1988): 575-599.

[15] Ibid., 585.

[16] Gil M. Doron, “…badlands, blank space, border vacuums, brownfields, conceptual Nevada, Dead Zones1, derelict areas…” in field, special issue: “Architecture and Indeterminacy” 1.1 (September 2007), 12.

[17] Robert David Lewis, “The Development of an Early Suburban Industrial District: The Montreal Ward of Saint-Ann, 1851-71,” Urban History Review 19.3 (February 1991): 166-180.

[18] Jean-Claude Marsan, Montreal in Evolution: An Historical Analysis of the Development of Montreal’s Architecture and Urban Environment (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1981), 174.

[19] The influx of Irish immigrants in Montreal at this time was largely due to the Great Famine (1845-1850).

[20] Herbert Brown Ames, The City Below the Hill: A Sociological Study of a Portion of the City of Montreal (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972).

[21] Richard Burman’s homage to Griffintown, 20th Century Griffintown in Pictures (Montreal: Burman Productions Reg’d, 2010), is a visual essay on this collective spirit.

[22] André Lortie, The 60s: Montréal Thinks Big (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2004) 21.

[23] The relationship between class and space in Montreal is complex and marked by historical proximities of rich and poor. The economic fortunes of the city since the closure of the Lachine Canal in 1968 had a devastating effect on the Old Port and canal districts. The Old Port was the focus of a determined revitalization effort in the 1990s, and property values have shot up accordingly. Ville-Marie is the central business district of Montreal.

[24] Steven High, ed., La Pointe: L’Autre Bord de la track/The Other Side of the Tracks (Montréal: Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling, 2015).

[25] Steven High, ed., Canal: De la/From There (Montréal: Centre for Oral History and Digital Storytelling, 2014).

[26] With regard to the Wellington tower and its future as a site for cultural innovation, see Allen McInnis, “Dilapidated Wellington Tower to be reborn as cultural centre,” Montreal Gazette (on- line) 15 July 2015 http://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/dilapidated-wellingtown-tower- to-be-reborn-as-cultural-centre.

[27] In the late 1980s, British urban planning consultant Charles Landry coined the “Creative City” concept. See Landry’s The Art of City Making (New York: Routledge 2006); The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators (London: Earthscan, 2000); and, co-authored with Franco Bianchini, The Creative City (Bournes Green: Comedia, 1995).

[28] Janssen, “Urban Occupations Urbaines” (2014), 16.

[29] See Cummings.

[30] See, for example, Sophie Thiébaut, Richard Bergeron, Etienne Coutu, “Le Quartier Griffintown réincarné,” Mémoire présenté à l’Office de consultation publique de Montréal (Montréal: Projet Montréal, 2012) 16pp (web) http://projetmontreal.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/ document/Mem_Griffintown_OCPM.pdf.

[31] Michelle Lalonde, “Griffintown Residents Want Heads-Up on Plan B,” The Gazette 22 January 2009: A7.

[32] For example, Montreal-based architect Hal Ingberg described Griffintown as “dead” in response to a public presentation that co-author Janssen gave in 2010 on Griffintown’s long history of transformation. Janssen and Ingberg were participants in the “Ephemeral City” series of public forums (# 5 “Public Space”), hosted by the Canadian Centre for Architecture on 18 February.

[33] See “Griffintown,” Le Canal (web) nd. http://lecanal.ca/en/griffintown.

[34] Air Canada, in-flight magazine, “Canada’s Next Great Neighbourhoods: Griffintown Montreal,” enRoute, 28 September 2012) (web) http://enroute.aircanada.com/en/articles/neighbourhood-watch-montreal.

[35] Janssen elaborated on these ideas in her doctoral dissertation, “Urban Occupations Urbaines: Curating the Post-industrial Landscape,” Diss., Concordia University, 2014. The dissertation can be accessed here: http://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/978384/1/Janssen_PhD_S2014.pdf>.

[36] See www.urbanoccupationsurbaines.org

[37] Over forty artists participated in Urban Occupations Urbaines, including Hammond, who participated via her design alter-ego, pouf! art+architecture, which she founded with Thomas Strickland. See http://www.cynthiahammond.com/pouf.htm.

[38] Janssen details this process and her findings, which include a critique of “community” in the context of an entire neighbourhood swept up in construction, in “Urban Occupations Urbaines” (2014).

[39] On this concept see Grant H. Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004); and The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham and London: Duke UP, 2011).

[40] Igor Sadikov, “Protesters denounce gentrification of Southwest Montreal,” McGill Daily (online) 5 February 2014. http://www.mcgilldaily.com/2014/02/protesters-denounce-gentrification-of-southwest-montreal/>. See also Cynthia Hammond and Thomas D. Strickland, “Biting Back: Art and Activism at the Dog Park,” On∣Site Review 30, Ethics and Publics (Fall-Winter 2013): 6-11; Simon Vickers, “Making Co-opville: Layers of Activism in Point St-Charles (1983-1992),” MA thesis, Department of History, Concordia University, 2013; Jessica J. Mills, “What’s the Point? The Meaning of Place, Memory, and Community in Point Saint Charles,” Quebec, MA thesis, Department of History, Concordia University, 2011; Shauna Janssen, “Reclaiming the Darling Foundry: From Post-Industrial Landscape to Quartier Éphémère,” MA thesis, INDI Program, Concordia University, 2009; Danielle Lewis, “The Turcot Yards: Community Encounters with a Queer Sublime,” Montreal as Palimpsest 3 (Department of Art History, Concordia University, 2009): 27pp; Le Collectif CourtePointe, The Point is… Grassroots Organizing Works: Women from Point St. Charles Sharing Stories of Solidarity (Montreal: CourtePointe Collective, 2006); Brian Demchinksy, ed. Grassroots, Greystones, and Glass Towers: Montreal Urban Issues and Architecture (Montreal: Véhicule Press, 1989). See also Joseph Baker, “An Experiment in Architecture,” The Canadian Architect 18 (1973): 30-41. In 1970, Joseph Baker, an architect and professor at McGill’s School of Architecture, initiated the Community Design Workshop. Baker launched the Community Design Workshop in response to the deprived communities living in Montreal’s working class neighbourhoods lacking basic housing and public amenities. Baker is also featured working with the Community Design Workshop students in Michel Régnier’s documentary film, Griffintown (1972). See <http://www.nfb.ca/film/griffintown.

[41] The “Couloir Culturel/Cultural Corridor – Griffintown” was active from 2009-2013 and their presence is archived at <http://www.griffintown.org/corridorculturel/>.

[42] Our lab participants consisted of Montrealers from various neighbourhoods. We reached out to members of the general public via two social media platforms, facebook and a wordpress blog; and to residents of Griffintown via a poster and postcard campaign. We further reached out to members of the Concordia community (students, staff, faculty) who are residents of the South-West of Montreal or interested in that part of the city. We also made use of several existing communication networks, such as the Darling Foundry’s mailing list, which includes residents in the South-West, cultural organizations across Montreal, and members of the art community of this city. Our participants varied from workshop to workshop; some had zero connection to the South-West but were concerned with the politics of urban change more broadly, while others were long-term residents. Our participants included persons with reduced mobility, international visitors to Montreal, high-paid executives, under-employed artists, and students. A complete list of all participants’ names were included in our didactic panels in our exhibition, and in our exhibition publication. Our outreach encouraged several politicians to attend our exhibition, including the Mayor of the South-West, Benoît Dorais.

[43] We are grateful for the assistance, in this and all our labs, of Alyse Tunnell.

[44] Didactic panel description, Points de vue (exhibition), Darling Foundry, 24-28 September 2014.

[45] The film “Pathways” (Thomas Strickland, videographer and editor) can be viewed online at <https://vimeo.com/123375471>.

[46] The organizers would like to thank Arseli Dokumaci for providing an introduction to these themes during the first part of this lab.

[47] Renata Ribiero, participant, “Archiving Urban Change”, 23 August 2014. Translated from the original French by Micheline Chevrier.

[48] Isabelle Pichet, participant, “Archiving Urban Change”, 23 August 2014. Translated from the original French by Micheline Chevrier.

[49] Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007).

[50] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many, 226.

[51] Diane Saint-Laurent, “Approches biogéographiques de la nature en ville: parcs, espaces verts et friches,” Cahiers de géographie du Québec 44.122 (2000): 147-166.

[52] Latour has published several books on this subject and maintains a blog detailing his projects and discoveries: http://floraurbana.blogspot.com/.

[53] All specimens not included in the exhibition went into compost.

[54] See “Friends – Jessica Hart,” Points de vue (2014) https://pointsdevuemtl.wordpress.com/jessica-hart/.

[55] These members were, in order of leadership, Shauna Janssen, Thomas Strickland, Marie-France Daigneault-Bouchard, Noémie Despland-Lichtert, Camille Bédard, Chantale Potié, and Cynthia Hammond.

[56] From the beginning of the project, practical considerations decided that for the purpose of designing and executing the final display, we would work as a curatorial team, led by Shauna Janssen and her co-director, Thomas Strickland. With seven members on our team, only ten days to prepare the exhibition, and less than three days to install the exhibition, it was not possible to extend our collaborative process with our 100 project participants into the gallery. (Finding time for the seven members of the curatorial team to meet in the gallery at the same time was, alone, a challenge, given conflicting work schedules.) We informed the participants from the outset that this would be our process as well. But even if they did not curate the exhibition’s contents, all 100 participants participated directly in the exhibition in the sense that they produced those contents, themselves.

[57] Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Polity Press, 2012); Bruno Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik, or How to Make Things Public,” In Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, exhibition catalogue, Centre for Art and Media, Karslruhe, Germany (March 2005) 4-31; Rosalyn Deutsche, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Chicago, Ill.; Cambridge, Mass., Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts; The MIT Press, 1998).

[58] Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2002), 137.

[59] Ibid., 154.

[60] Ibid., 7.

[61] Our use of the term dialogue here is in keeping with Grant H. Kester’s idea of “dialogical aesthetics” and discursive forms of creating meaning. Kester is articulating a critical framework for social art practices, and the capacity for dialogue to create an aesthetic experience. See Kester, Conversation Pieces, 2004.

[62] Our project led one of the team finalists in the design competition, Eastern Bloc and Espace temps, to approach us to collaborate on their final proposal to the city in May 2015 via a partnership with Concordia University. This team did not win the bid for the retrofit of the tower, but we still felt that our work had been successful in that this team began to engage more directly with the built, social, and environmental histories, as well as divergent voices and positions within Montreal’s South-West, in their thinking and proposal.

[63] Marie-France Daigneault-Bouchard, one of Points de vue’s curators, discovered during our Spatial Justice lab that several representatives of one of the finalist teams were using our end-of-day group discussions to ask participants their opinion about possible features in the future redesign of the building, such as the location of cafés. They also did not identify themselves to their group as design finalists. As our purpose in this lab was explicitly to deal with questions of accessibility, Marie-France asked the individuals to reorient their participation in the discussion, and remained with the group to ensure that spatial justice remained the topic in question.

[64] Dire as this sounds, this problem has provided us with an opportunity to build an ongoing, open discussion about the ethics of shared authorship, the politics of collaboration, and the need for peer-to-peer consultation and mentoring in this type of work.

[65] The majority of our funding came from Concordia University’s Aid to Research-Related Events Program, but some much-needed additional funding also arrived, thanks to Shauna Janssen’s lobbying, via the Darling Foundry. And during the intense few days of installation leading up to the exhibition’s opening, Pierre Giroux, the Darling Foundry’s technician, provided assistance and support late into the night, long after gallery closing time.

[66] Henri Lefebvre is most associated with this term, which understands all citizens as having the right to speak out about, occupy, and change their city. The Right to the City: Writings on Cities, E. Lebas, trans. (London: Blackwell, 2006) 147-159. See also David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” in The Right to the City, Zanny Begg and Lee Stickells, eds. (Sydney: Tin Sheds Gallery, 2011) 11-28: Margaret Crawford, “Rethinking ‘Rights’, Rethinking ‘Cities’: A Response to David Harvey’s ‘The Right to the City,’” in The Right to the City, 33-37.

[67] Mouffe, “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces,” Art and Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 1.2 (Summer, 2007): 3. http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/mouffe.html

[68] See Mouffe, “Artistic Activism,” 4.

[69] We make a distinction between art-as-entertainment and art collaborations with the city as a means to enchantment. Jane Bennett describes the “wonder of minor experiences” as different from blockbuster, high-budget urban spectacle, in that the former are more intimate, personal, and embodied. See “The Wonder of Minor Experiences” in The Enchantment of Modern Life (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001) 3-16.

[70] Exhibition commentary from the Points de vue visitors’ book, September 2014, comment by Manon S. Russo. Translated from the original French by Cynthia Hammond.