The Green Room: Off-Stage in Site-Specific Performance Art and Ethnographic Encounters

George E. Marcus

In the villa on Lake Geneva that is the home of the World Trade Organization there is in the Director General’s suite a Green Room. Here nations come to terms, make deals, and sometimes fail to make them, but more importantly, and I would like to say, paraethnographically,[1] define the distinctive terms of their relationships, which are then played out on other more public stages. This room and what goes on inside it, what it stands for in the WTO process and politics has been an object of fascination for me and the others currently involved in a team ethnography of The WTO, directed by Marc Abeles of the EHESS in Paris. The example of the Green Room at the WTO, itself a key scene of ethnographic interest, will serve me as a metaphor for the further links I would like to make between the tradecraft of a changing and refunctioned ethnographic fieldwork as a mode of inquiry today and that of performance and site-specific installation art from the 1990s forward. There is an affinity between ethnography in its post-1980s predicaments (not so much textual as indeed performative) and the relational aesthetics of the 90s and the still current performance art that it has reflected. But while performance art by the late 90s had gotten over, or rather, qualified, its attraction to ethnography,[2] ethnography, in trying to reconceive fieldwork in its anthropological tradition, still has much to learn from performance art about how to give form to its inquiry in the multiplicity of worlds and publics in which any such project moves, and in which it is still expected to articulate something distinctive and specific about its subjects.[3] Performance art delivers spectacle; ethnography now delivers descriptions as concepts about contemporary life, as scenes of emergence of social change toward an anticipated or definable near future. To do so, both need to engage actors as collaborators, to create designs out of natural settings, to show care for audiences as dynamic, as a public, and to be aware of the ethics of staging.

After the 1980s “Writing Culture” critiques of ethnography and anthropological representations of the cultural practices of their subjects,[4] the interesting theoretical problems of anthropology have not continued to dwell on its textual representations, but rather have focused on its forms of ‘doing,’ its designs of fieldwork. So, as one who continues to be interested in anthropology’s powers of interpretation, explanation, and capacity to participate in, and inspire public dialogues, I have become something of a technologist of—perhaps an experimenter with—its habitual forms of inquiry,[5] and in this effort, the modes of producing performance art have been a fertile place to look for inspiration, after its own brief romance with ethnography.

The Green Room is such a valuable linking metaphor since, while being an institution of theater, it suggests the considerable debt to the making of theater that performance art owes and can transfer to ethnography through its own tradecraft.[6] Indeed in the refunctioned ethnography that I and others have been imagining in a myriad of current schemes and conceptual registers, it is clear that imaginaries of staging, workshop, and a space or ground of conceptual aesthetics needs to emerge within every fieldwork project today. And the Green Room, as seized upon literally and symbolically by the WTO for its purposes, is not a bad metaphor for such a space of collaboration and negotiation of coming to terms with what are experiments, be it in the WTO, performance art, or ethnography. I am interested in these experiments, often found or serendipitous, but then strategized, at the heart of research that occurs within the bounds of projects of fieldwork in ethnography and of research that goes into the staging of performance art.

The Green Room is the place of extreme reflexive specificity and anticipation—the last bit of staging, where the singularity of each performance is negotiated, so to speak, by actors—it is not rehearsal, it is not dramaturgy, but the mediating space between those exercises and performance. Analogously, contemporary ethnographic fieldwork needs a Green Room built into its process, and what might go on within this space both materially and symbolically is suggested by the research that goes into projects of performance art and site-specific installation. I want to further engage the link between the fieldwork that contemporary ethnographers do and the research that performance artists do in their projects. While I am personally beguiled by the theatrics and theatrical contexts of the Green Room, as the moment, in its place, of reflexivity before a singular performance, the last stage of staging, I find its metaphorical transference suggestive of the function in both performance art projects and those of ethnography of spaces of distinctive conceptual control and interpretation, either on the subtle edges of spectacle or fieldwork, or as embedded in this process of each as giving form to process. As with the WTO, which has seized upon the Green Room for its own paraethnographic and reflexive purposes, it is the materialization of the imaginary of the space of negotiation, of coming to terms, of the distinctive concept work that it does amid the high stakes political economic relations between nations that it congregates. Every performance art project materializes such a space of practice as does every project of contemporary ethnography. And it can take quite unpredictable forms. The Green Room might then be thought of as a site of fieldwork and a site of performance that does important work for each of them internal to their production. How it is staged, realized, and designed is part of the tradecraft of both, but under present conditions, I believe ethnography can learn more from performance art than vice versa.

At the Tate Modern

During the 1980s and 1990s, while anthropology was critiquing its historic method and its performative expression as ethnographic text, there was a parallel interest in socially conscious art. This mainly took the form of installations, performances, and happenings, and was influenced heavily by the enthusiasm for cultural theory during this period. Nicolas Bourriaud has famously written about art of the 90s (into the present) as ‘relational aesthetics’, describing the orchestration of sites, settings, and social actors, and processes for certain effects that have complex social topologies investigated through background research (like fieldwork) but are realized in a scene of spectacle.[7] In this case, spectacle is conceived as a symbolic act, stimulating a critical reflexivity on the part of participants and observers. For example, Rirkrit Tiravanija organizes a dinner in a collector’s home, and leaves him all the ingredients required to make a Thai soup; Philippe Parreno invites a few people to pursue their favorite hobbies on May Day, on a factory assembly line; Maurizio Cattelan feeds rats on “Bel Paese” cheese and sells them as multiples, or he exhibits recently robbed safes.

Hal Foster’s 1995 essay “The Artist as Ethnographer?” explicitly addressed the pretension to ethnography and to research as fieldwork in this array of art projects, and he did so with an informed skepticism and acute cynicism. But the limitation of Foster’s assessment is that he was measuring the ethnographic pretense and prowess of the artist in terms of the uncritiqued, relatively unproblematic pre-1980s condition of anthropological ethnography—how anthropology is stereotypically known to its publics. Ethnography in its post-80s formation is very different, and needs very much, I would argue, the sort of play with its practice that artists have been engaged in, and about which Foster was skeptical. As I will explore in more depth, the kind of research undertaken by artists may be seen as a model that anthropologists can think with in articulating manifest changes in their own traditions of fieldwork.

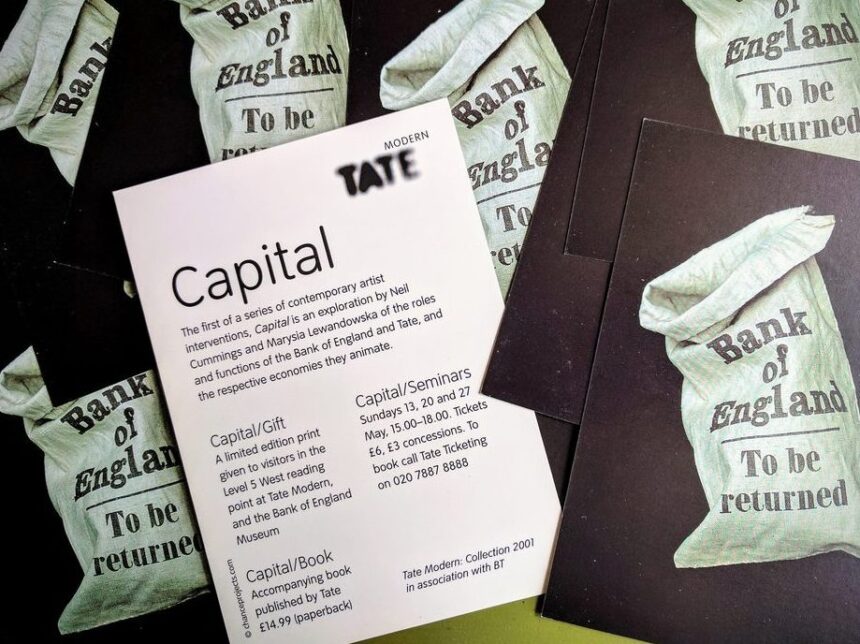

I have found that many of these art projects are concerned either with questions of collective trauma and suffering as a challenge to a smug humanitarianism; with identity and difference among peoples and places in a globalizing world (e.g., the scenes orchestrated by the artistic collaborative, Stalker, in various places of a demographically changing European landscape, discussed by the sociologist of art, Nikos Papastergiadis, as probings into the situated practices and potentials of cosmopolitanism in ethnically diverse situations); or else deal with the material processes responsible for globalization: systems of value, exchange, markets, rethinking capitalism in the cultural sphere (e.g., the projects of Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowksa that deal with art institutions, value, and capitalism). These are of course the core generic topics and preoccupations of anthropological research as well, making the affinity with the general form of these projects even more suggestive for ethnographers who everywhere today, it seems, are confronted with a negotiation about reflexivity in order to materialize both an object and a space-time of research. The openness and experimental nature with which artists in the movement that I have been describing are doing fieldwork, so to speak, to occupy the scene of spectacle that art produces, are valuable exemplars for articulating systemic changes in the mythic scene of encounter in contemporary anthropological research. As an example of this, I will focus on the project Capital by Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska, and assess its potential to articulate emergent changes in fieldwork practices in anthropology.

In September 2003, I attended a large, diverse, and ambitious conference at the Tate Modern, entitled Fieldworks: Dialogues Between Art and Anthropology. My talk there shared concerns with this essay; I was in conversation with Hal Foster’s critique of the effort of artists to do something like ‘ethnography’ and I reflected on my collaborative participation with artists from Cuba and Venezuela in the production of a series of installations and performances. Among the variety of projects and approaches, I was riveted by a 36-minute account by Cummings and Lewandowska of the process by which they had produced an intervention for the Tate Modern in 2001. I thought what I was hearing at the time was an account of the alternative model of fieldwork that I had been conjuring for anthropology. Such a behind-the-scenes account is valuable, since it rarely appears amid the genres by which artists make their work public, or do advertisements for themselves (for example, what represents this project, besides website material, is an attractive and glossy Tate catalogue publication, entitled simply Capital; there was also a series of Tate sponsored seminars, plus an intervention in the scene of the museum itself). I indeed heard what I thought I had, but there were several other nuances in the presentation that made me appreciate how the construction of their project differs from ethnography as well.

Cummings and Lewandowska, who have been working together since 1995, have done numerous projects for which a period of initial research is necessary. Most importantly, this research replaces the site specificity of art. Any project of course involves physical locations, but more importantly the project’s site is a social imagination that is conceptually invented and materialized in the practices of research or investigation based on a deeply reflexive motivation. The scene and bounds of fieldwork, or of a project emerge through following a set of relations across a social landscape that it is both material and imaginary. Research is a design of collaborations and other sorts of engagements of varying intensity. Regardless of how, and to what critical response, they finally filled in the scene of spectacle as art in the Tate project that they undertook, their research in this project is important, I believe, as an example of the ongoing transformations of the classic scene of encounter in anthropology—the anthropological fieldworker constituting a site of research by dwelling there, joining in its form of life, and acting as a human instrument of observation with the collaboration of others.

In a text accompanying the project, Cummings and Lewandowska began with this manifesto-like statement:

We recognize that it’s no longer helpful to pretend that artists originate the products they make, or more importantly, have control over the values or meanings attributed to their practice: interpretation has superceded intention. It’s clear that artworks and artists exist in a larger economy of art; built from an interrelated web of curatorship, exhibitions, galleries, museums, archives, places of education, various forms of funding, dealers, collectors, catalogues, books, theorists, critics, reviewers, advertising, and so on.

In the light of the above, we have evolved a way of working over the last few years which requires an intense period of research with the various institutions of art. We have initiated projects with museums, retail stores, commercial and public galleries, as well as places of education. These collaborations have resulted in a number of different outcomes appropriate to the nature of each project; exhibitions, collections, books, guided tours, lectures, videos, an internet browser, and a range of promotional or educational material. We are interested in working alongside all of the institutions that choreograph the exchange of people and things.[8]

In their Tate commission, Cummings and Lewandowska were given free rein to develop a reflexive installation or intervention at the Tate Modern. They were very much influenced by the sort of theoretical writings that motivate anthropological research on exchange, value, and material culture, including Nigel Thrift (and his important argument that the experience of the modern world is increasingly insubstantial, meaning that ethnography about any local condition is always pulled ‘elsewhere,’ and this requires strategies of creating, through inquiry, social imaginaries that are at least multi-sited), and most interestingly Marilyn Strathern (Cummings and Lewandowska work brilliantly with some of Strathern’s New Guinea analogies). They created an imaginary for their project that turned on the analogy and homology between the massive and powerful Tate Modern as the central arbiter of value in the symbolic economy of art and the Bank of England just across the Thames as the central arbiter of the secular money economy, the lender of last resort, managing the price of debt, and cost of borrowing. Based on their Tate connections, Cummings and Lewandowska were able to conduct interviews in the Bank of England and gain the cooperation of some of its officials. The intensity of their project became centered on this juxtaposition, this back and forth between the two institutions, symbolically, conceptually, and literally. The critical probe and resolution of this juxtaposition was resolved in using ideas of ‘the gift’, a classic, foundational theory in the anthropology of exchange, which permeates the work of Strathern and others.

Cummings and Lewandowska wanted to create an intervention in the museum that would make invisible gifting relationships that sustain major cultural institutions visible to museum visitors; they wanted to suggest the symbolic relation between the Tate and the Bank of England as well. While the research process itself became the most important part of the research, they finally did create something, a gesture to fill the scene of spectacle, instead of an art object. At selected times arbitrarily chosen visitors to the Tate were given a limited-edition print, issued by the artists, through a gallery official. This unexpected gesture was to act like a detonator, raising many questions about the nature of the gift.

There are many ways in which this project can be critiqued. Did its intervention really work as critique on any level? The research was not engaged enough, did not really respect its collaborators, perhaps, and their generative capacity to generate insight and self-critique. While the project was ethnographic at its heart, its thinking was ironically distanced and highly theoretical. It did not take the politics of research that it created far enough. But then why should it? The purposes of art should not be mistaken for the purposes of ethnographic research. Indeed, there was one really strange moment in Neil Cummings’ presentation when, in referring to my own prior discussion of Hal Foster’s essay in my conference talk, he said that the artist’s use of something like fieldwork should not be associated with participant observation (and presumably the fieldwork model) in anthropology—he presumed that reflexivity in anthropological ethnography is about ethical discipline (actually he is not wrong about this), but that artists are not capable of this function. They are interested in something else, he said.

Indeed, there is something ruthless and manipulative in the management of relations in Cummings and Lewandowska’s Tate project—they do not work in the ethics that hovers over and shapes the implicit moral discourse of the classic scene of the fieldwork encounter. They are after an insight and the production of an effect, an effect of critical reflexive insight, which is its own virtue of doing good. For the sake of this, their research relations are rather instrumental and businesslike. I think this orientation would be both disconcerting and liberating to anthropologists, especially those who must constitute fieldwork today out of multiple sites of activity and community. Finally, then, their research, while set up in ways from which anthropological ethnography could learn a great deal, does not care enough about the politics of the process of inquiry that they set in motion and what kind of unique knowledge it could produce. Instead, they heavily relied on theory, and the authority of academics. This is fair enough, given their purposes and the real differences of these from the purposes of anthropology, but they have given us a sample of what field work is in fact becoming in anthropology.

Let’s consider some of the important lessons that they develop for the refunctioning of the ethnographic project in anthropology. In so doing, it might be appreciated that the anthropological practice of fieldwork is not just a technology of method, but is an aesthetic of method as well that is powerfully inculcated by professional culture and identity. As such, in reinventing fieldwork for its present conditions, aesthetics will not be denied, or at least won’t be changed without compensation in whatever idiom. In short, in reinventing fieldwork, it is a certain powerful and established aesthetic that is being addressed in offering a new design and this is at least as important as the appeal of the techniques themselves. So what are the aesthetic compensations within Cummings and Lewandowska’s critique of a certain romantic mise-en-scène in which anthropological science was classically performed?

1. The scene of encounter in contemporary ethnography leads away from a literal site-specificity to fieldwork.[9] Their Tate project shows convincingly how this might happen or evolve as a practice of research. They have a sense of how to use reflexivity to generate a field of relations that is more sophisticated than anything in the habit of anthropological fieldwork. Cummings is correct that reflexivity in the classic scene of the fieldwork encounter has been developed in the interest of ethical discipline or moral correctness. For the artists, reflexivity is a strategy used to generate a space of social imagination which connects an artistic or intellectual discipline to its contexts as its major means and ends of inquiry. The situated collaborative work which is required to generate a social imaginary for fieldwork in which the researchers literally move and operate is the aesthetic compensation for the loss of the classic scene of encounter. The encounter here is with a found intellectual partner, a friend, in the face of a more abstract unknown than a literal place—a relation, a system, what historian of science Hans–Jörg Rheinberger calls an epistemic thing.

Cummings and Lewandowksa operate in the historic mode of modernist artistic practice—the space of the experiment—and to some degree their research is encompassed by this idea, investigation materially in an imaginary of a trial, trying something out for a result—here a performance and intervention as occupying the artistic scene of spectacle. The 1980s critique of the anthropological scene of encounter also introduced something of this artistic idea of the experiment to anthropology —the idea that ethnography is an experiment and that there was even something of this in the originary projects of Malinowski, Firth, Evans-Pritchard, and others. The critique of the tropes of ethnography would not have been possible without this evocation of fieldwork as experimental in the artistic sense.

In recent years, experimentation in terms of the natural sciences has been rethought in ways that overlap closely with these art practices and the overlapping sense of experimentation in ethnography. Rheinberger’s writing has been especially influential among anthropologists working in science and technology studies, a burgeoning arena in which the sort of refunctioning that I have been articulating here has most manifested itself in practice. The account that he gives of scientific practice in pursuit of epistemic things resonates with ethnographic inquiry, revised from the regime of conventional empiricism that was its originary model.[10] This overlap of an artistic and scientific aesthetics of practice around the notion of experiment has been one of the more promising background conceptual environments for carrying out the refunctioning of ethnography at the intersection of art and anthropology that I have been discussing here. So, then, experiment may be understood as the ground of compensating aesthetics for the refunctioning of the classic scene of the fieldwork encounter toward a viable idea of multi-sitedness or non-site-specific fieldwork.

2. Within this reflexively evolved terrain of inquiry, the focus or object of study emerges through the intensity of an operation like juxtaposition as a probe of inquiry and mediation within an imagined and literal space. I want to argue that it is in constructing these intensities of juxtaposition that one prominent space and function analogous to the Green Room materializes both in performance art and ethnography today. The aesthetics of spectacle and the concept work crucial to the form of ethnographic research emerge in each case in the coming to a powerful, emotive juxtaposition. This juxtaposition is not the performance of spectacle itself nor the form of the ethnographic text, but it is the decisive coming to terms or shaping of performance, either in art, anthropology, or in formal diplomatic organizations, negotiation.

The intellectual work that led to the connection between the Tate and the Bank of England in Cummings and Lewandowksa’s project suggests the sort of conceptual labor or intense focus on relations at the heart of ethnographic knowing in contemporary fieldwork. Cummings and Lewandowksa give up, they go only so far, they let theory do the work, they impose insights rather than develop sustained collaborations with found counterparts, but they do demonstrate how a different sort of object emerges from fieldwork that is carried out in a multi-sited space or imaginary.

The intensity of juxtaposition points to a relation that generates an aesthetic suggestive of working in an environment of difference so essential to fieldwork in the anthropological tradition. It is a remnant or residue of the liking for the exotic, where the literal exotic no longer exists, and what’s more, has been critiqued to the extent of being unclaimable. In the revised terms of the experiment that I have just discussed, the juxtaposition is the operation that creates the epistemic thing—in Cummings and Lewandowksa’s project, it is thinking of the Tate as an economy, in which its relation to the Bank of England is not simply metaphorical, but manifest and material in relations of the gift, so to speak, and in the relations that their research produced, made possible pragmatically by the found connections between the Tate and the Bank of England, both imaginary and real.

3. The aesthetic compensation for life in situated communities associated with the classic scene of ethnography is visible in the intellectual collaborations found in fieldwork—mutual aid in pursuit of a common object. Refunctioned ethnography indeed depends on the development of this aesthetic long submerged in traditional ethnography, but now takes to different levels expressions of complexity, and expectations of practice.

4. Perhaps most consequentially what Cummings and Lewandowksa’s Tate project suggests for the refunctioning of ethnographic research in anthropology is a different modality of purpose and result for ethnography. Mediation or intervention replaces or pushes from primacy the production of conventional description and analysis leading to an ethnographic text of the usual purposes, as a contribution to theory, or as an archive of knowledge accumulated by a collective of disciplinary scholars, devoted to a discipline. Indeed, in this sense, the ethnography may very well be outmoded. Other genres serve these functions better, and now do the kind of description that ethnography used to do of its old objects just as well, if not more cogently in its new terrains of interests. In any case, there is no representation that is unique to anthropology and, especially for its new objects of research, no collective or specialized disciplinary guild or community for it. It is already the case that ethnography is most important to constituencies that are already found in fieldwork. Yet, anthropology does not exactly know yet how to conceive such a function. In the US at least, there is talk of a public anthropology, and claims to activism in its intellectual work. To me, neither of these is convincing. They are symptoms of the uncertainty of purpose of a research practice that once justified itself as part documentation, part analysis in relation to a growing edifice of general, theoretical knowing about a circumscribed subject matter. The results of ethnographic research today are less clear, certainly more specific, and indeed more ethnographic in quality. This means that ethnographic knowledge creates itself in parallel with and relation to similar functions in the very communities which it makes it subjects. This leads to the more urgent need for modalities of collaboration as method, already mentioned, but also to mediation and intervention as being the primary form and function of the knowledge that ethnography produces. This is similar to what Cummings and Lewandowksa attempted in their intervention at the Tate, but in a more limited and frankly more superficial way than the more patient, sustained, and ethical relations of ethnographic research in anthropology—something that they rejected as obstructive to their purposes as artists. The cliched participant observation of traditional ethnography for the archive here is replaced by an aesthetic of collaborative knowledge projects of uncertain closure.

What Is, Where Is, The Green Room in All This?

While the spectacle or the performative act in relation to the public in the Tate project of Cummings and Lewandowska was the gesture of a gift offering to museum visitors, in the project’s research, design, and rationale the sustained act in which the critical thinking for this spectacle was done was the ethnographic-like inquiry moving back and forth between the Bank of England (in which site interviews and observations were done) and the Tate Modern (in which similar inquiry was done). This dynamic of juxtaposition led to seminars with academics, artists and others that paralleled the production of the act of spectacle. In this process, then, the figural Green Room involves the discussions, the paraethnography, that the juxtaposition of sites of fieldwork-like investigation stimulated, alongside the planning and performance of the spectacle of gift-giving. This process is a quite explicit expression of a similar sort of reflexive concept work that goes on today within fieldwork and defines the objects and subjects of anthropological ethnography. While ethnography might still report ritual, life in community, and the experience of distinctive cultural subjectivities, it does so, not within the milieu of a governing, holistic culture, but in the inventive configuring of a multi-sited terrain of activity in which the dynamic of juxtaposition of sites, with different kinds of rationales, plays a key role in the production of ethnography. I presume something of the same kind of inspirational, urgent concept work in body and mind goes on among actors in the Green Room.

I have described this process as the emergence of an imaginary for every project of fieldwork today, on which the performance of ethnography, usually in texts and writing, depends for its dynamic, concept, and expression of argument. Like the Green Room in theatrical performance, the experimental quality of fieldwork remains integral, but largely invisible, private, or off to the side, in relation to the public form of ethnographic expression in text. In fieldwork projects with which I have been associated or supervised, this kind of Green Room effect in the production of research has been most vividly exemplified and made explicit in those which have worked through the study of a distinctive aesthetic form or genre juxtaposed to fieldwork situated in quite messy arenas of contemporary everyday life and social change among situated peoples and places in history.

Classically, Jean Rouch’s Les Maîtres Fous evokes this ecology of fieldwork built on the intensity of juxtaposition between rather anonymous life in colonial modernity and a co-existing arena of cultural reserve where an allegorical critique of, or response, to that life occurs, in a private space, alongside it. In the projects in which I have been involved, ethnographers have immersed themselves in the study of a particular cultural aesthetic form while they in parallel have investigated contemporary social and cultural conditions of a group of subjects caught up in transformation of some sort. Never in any of these projects is there a simple reduction of the complexity of social life observed to an explanatory principle or defining cultural premise extracted from the study of the parallel aesthetic form. Rather the inventiveness of the fieldwork is in finding a more complex relation between the sites of juxtaposition. The projects that I am familiar with have mediated, for example, a decades long ethnographic study of tango with the problem of political violence in recent Argentine history; the study of arabesque with the practice of elicit adoption in Moroccan society; the study of tattooing with the experience of the loss of status in contemporary Samoan culture, and most recently (and brilliantly) the study of Persian miniature painting at the Freer|Sackler galleries in Washington, D.C. with the pursuit of fieldwork on the politics of prominent Iranian exile organizations in Washington during the “War on Terror” atmosphere of the Bush administration.[11]

In each of these projects, the realm of aesthetic production is like a Green Room, or lab for experimental thinking, in conjunction with linking such a site to the quite typical setting of ethnographic research today, not in terms of the study of the essentials of a culture, but as symbols, values, identities, and peoples in states of transition. The ability to evoke the resonance of performance in an anthropological context depends on Green Room strategizing of a site’s configuration and associated cultural concepts

The intensity of juxtaposition amid sites is just one, albeit rich, mode among others in which the figure of the Green Room materializes in the theatrics of fieldwork today. This figure can also emerge within quite traditional and classic scenes of fieldwork encounter in which the negotiation of collaboration defines the stage, so to speak, of fieldwork, rather than to presume the entrance of the participant observer into a natural setting of social life and action. Yes, dramatic events, rituals, conflicts, and interactions remain the key materials for ethnographic study, but their occasion for observation—their status as performance—depends deeply on the kind of Green Room reflexive work that has been negotiated with key collaborators who act as patrons, subjects, and complicit partners of the fieldworker.[12] For a wonderful account of the Green Room effect emerging as a lesson learned in the pursuit of fieldwork in its formative, historic phase, see James Clifford’s essay on the research of Marcel Griaule.[13]

Epilogue

The central tendency in American anthropology today is to strive to produce “Public Anthropology.” There is a lot of ideology, ambition, and old and new thinking behind this term, but it has given rise to fresh thinking about the norms and character of ethical practice in anthropological research, beyond the classic emphasis on and critiques of the care of the relationship between anthropologist and her subjects in the context of fieldwork. At least for the past three decades ethical discussions in anthropology have dwelt primarily on the implication of the colonial contexts in which ethnographic research was pioneered. While as the terrain and subjects of fieldwork have become more varied, and indeed the range of issues in ethical concern has begun to broaden, it is still the case that anthropological ethics are mostly about the relation to the subjects in sustained periods of fieldwork, where the anthropologist is presumed to have more social power than the latter, on whom they are nonetheless dependent for cooperation and hospitality.

As I noted previously, I was struck by Neil Cummings’ comment during the conference at the Tate Modern that artists who might be doing something like fieldwork should not be considered the same as anthropologists because they did not have their ethical discipline. I presume he meant that artists for their purposes were not often engaged in the same intensity of relationship or stakes with their research—that while perhaps caring for their own fieldwork relations they did not have the same level of ethical concern, or ‘discipline,’ as anthropologists. I found this distinction interesting and it implied a kind of ethical relativism. I have been thinking subsequently more about this distinction with the shifting weight of ethical discussion in ‘public’ anthropology in mind. While not presuming to judge or generalize about the nature of the ethical concerns of all performance/site-specific artists, I would like to propose that in relative terms, the weight of ethical concern of artists is vested in the effect of spectacle, the relations to the viewing audience and public, and the concern with their work being seen and the ethics of performance. Relative to this the ethics of the ‘Green Room,’ so to speak, of the process of inquiry, and what shares affinity with fieldwork, is of less importance, or less emphasized. The relation to subjects, may even be ruthless and manipulative from the vantage point of the anthropologist. In any case, Cummings interestingly admits to a lack of ethical discipline in fieldwork relations, relative to anthropology, with a careful and subtle concern about the ethics of spectacle instead.

Anthropologists do not care about ‘being seen,’ but they care deeply about their working relations with colonial and postcolonial subjects in the encounters of fieldwork. Yet, in the pursuit of ‘public anthropology’ they are increasingly sensitive to audiences and broader publics of reception for their work beyond how professional ethics have been traditionally defined. And this requires an ethical sensibility that comes closer to where performance artists have placed the emphasis—the timing of disclosure, spectacle and performance in implied contracts with audiences and public attention. If there is validity to this relative difference in ethical attention and care between ethnographers and performance artists, then anthropologists have something to learn about the emerging spectacular futures of their work, while still being critical, if not occasionally disturbed, by a perception of a lesser concern for ethical discipline. The difference in relative weightings of ethical concern is thus a promising way to think about the differences between anthropological ethnography and site-specific performance art.

George E. Marcus is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Irvine. He has researched and written about nobility in Tonga, an upper-class group with family fortunes in Galveston, Texas, and a Portuguese nobleman. In his books Writing Culture and Anthropology as Cultural Critique, he argued that anthropologists typically frame their thoughts according to their own social, political, and literary history, and are inclined to study people with less power and status than themselves. Marcus’s current research focuses on institutions of power and their relationships with ordinary people.

Image: Neil Cummings, Capital, Tate Modern May, 2001

Notes

[1] The para-ethnographic is a self-conscious critical faculty operating in domains of expertise and craftsmanship as a way of dealing with contradictions, exceptions and facts that are fugitive, suggesting a social realm and social processes not in alignment with conventional representations and reigning modes of analysis. Making ethnography from the found para-ethnographic redefines the status of the subject or informant and asks what different accounts one wants from such key figures in the fieldwork process. The para-ethnographic is deeply connected to the long-standing interest in American cultural anthropology of probing ‘native points of view’ through ethnographic investigation.

[2] Hal Foster, “The Artist as Ethnographer?,” in The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology, ed. George Marcus and Fred Myer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

[3] George E. Marcus, Ethnography through Thick and Thin (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998).

[4] James Clifford and George E. Marcus, Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

[5] Paul Rabinow et al., Designs for an Anthropology of the Contemporary (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008). James D. Faubion and George E. Marcus, eds., Fieldwork Is Not What It Used to Be: Learning Anthropology’s Method in a Time of Transition (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009).

[6] A Green Room is a room in a theater, studio, or other public venue for the accommodation of performers or speakers when not required on the stage. In some theater companies, the term Green Room also refers to the director’s critique session after a rehearsal or performance. It involves mind/body thinking and reflection of actors, meta to, but intimate with the performance to which it is adjacent. The first recorded use of the term is in 1701 and the name evokes the limelight, the soothing aspect of the color green. In Shakespearean theater, actors would prepare for their performances in a room filled with plants and shrubs. The “Green” was a traditional term of actors for the stage, and the Green Room was a stopping point on the way to the stage. For me, its importance is that it encompasses the reflexive work that is invisible in relation to performance but brackets and inhabits it.

[7] Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 1998).

[8] For more info about the project see “Capital,” Neil Cummings, http://www.neilcummings.com/content/capital

[9] Fieldwork is no longer site specific in a literal sense. It has become multi-sited, not in the sense of making classic scenes of fieldwork encounter many times over but through a different strategy of materializing the field of research at certain locations—these are questions of scale-making, a located, situated logic of juxtaposition in which fieldwork literally and imaginatively moves and is designed as such. The object of study is not a particular cultural structure or logic to be described, analyzed and modeled, but defining and working within, mediating certain relations by social actors who are both subjects and partners in research.

[10] For example: “Experimental systems are to be seen as the smallest integral working units of research. As such, they are systems of manipulation designed to give unknown answers to questions that the experimenters themselves are not yet able clearly to ask. Experimentation as a machine for making the future has to engender unexpected events. Epistemic things are material entities or processes- physical structures, chemical relations, biological functions—that constitute the objects of inquiry. As epistemic objects, they present themselves in a characteristic, irreducible vagueness. This vagueness is inevitable because epistemic things embody what one does not yet know. Scientific objects have the precious status of being absent in their experimental presence…” Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1997).

[11] Nahal Naficy, “Persian Miniature Writing: An Ethnography of Iranian Organizations in Washington, DC” (PhD diss., Rice University, 2007).

[12] For example, I have recently published an account of a collaboration with a Portuguese aristocrat, Fernando Mascarenhas, the Marques of Fronteira and Alorna, who was at once, patron, partner, and subject in this research [George E. Marcus and Fernando Mascarenhas, Ocasião: The Marquis and the Anthropologist, a Collaboration (AltaMira Press, 2005)]. It is called Ocasiao, a term rich in meaning both for Fernando’s house and our experiment in ethnography. This account is a transcript of our initial discussions via email. While superficially resembling a reflexive account of fieldwork in the classic mise-en-scène typical of the genre that followed the Writing Culture critiques, in fact it is an account of the development of a different architecture or design from our collaboration that involves creating a multi-sited imaginary for this particular project, materialized as a system of nested dialogues and discussions with orchestrated reflexive commentaries on the corpus of material as it was accumulating in this form; the climax of this study was a conference of Portuguese nobles held at Fernando’s palace in 2000. This was a rather rarified subject, but finally it incorporated many of the aspects of the practice of fieldwork explicit in the project of Cummings and Lewandowksa and implicit in many contemporary projects of anthropological research. In short it was a theater of reflexivities modulating nested occasions of discussion, increasingly enriched by a recursivity that comments on earlier materials. This was a project full of mediations, interventions, reactions and receptions within its bounds; for anthropology, the academy, and others there are a set of publications which reflect its contents in the conventional genre tropes of anthropological writing, analogous to the way in which Cummings and Lewandowksa resolved their project into the genre of the glossy, theoretical, semi-academic museum catalog publication as just one of its publicly expressive forms. In this publication the processes of producing the project were hidden, made available only in the informality of the conference presentation at the Tate; in the case of our Portuguese project, the comparable publication—the ethnographic work—was entirely devoted to the process of the research and thinking it through collaboratively. Surely this says something about the state of ethnography in anthropology, where its process inside out is of more immediate or priority interest in a general way than its results. Indeed, the most interesting ethnographic works today have this inside-outness quality where quite substantive results, understandings, analyses of processes, things in the world are woven into a reflexive account of how the project itself as an act of research comes into being or evolves. This is far from the charge of narcissism and so-called self-indulgent reflexive ethnography so frequently written and even more feared after the 1980s critique. Such an account is actually relevant to its intellectual function and scope, as evoked by the figure of the Green Room in this paper.

[13] James Clifford, “Power and Dialogue in Ethnography: Marcel Griaule’s Initiation,” in The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Bibliography

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les presses du réel, 1998.

Clifford, James. “Power and Dialogue in Ethnography: Marcel Griaule’s Initiation.” In The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art, 381. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Clifford, James, and George E. Marcus. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Cummings, Neil. Capital: A Project by Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska. London: Tate publishing, 2001.

Faubion, James D., and George E. Marcus, eds. Fieldwork Is Not What It Used to Be: Learning Anthropology’s Method in a Time of Transition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009.

Foster, Hal. “The Artist as Ethnographer?.” In The Traffic in Culture: Refiguring Art and Anthropology, edited by George Marcus and Fred Myer, 302–309. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Kester, Grant H. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Marcus, George E. Ethnography through Thick and Thin. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Marcus, George E., and Fernando Mascarenhas. Ocasião: The Marquis and the Anthropologist, a Collaboration. AltaMira Press, 2005.

Naficy, Nahal. “Persian Miniature Writing: An Ethnography of Iranian Organizations in Washington, DC.” PhD diss., Rice University, 2007.

Rabinow, Paul, George E. Marcus, James D. Faubion, and Tobias Rees. Designs for an Anthropology of the Contemporary. Durham: Duke University Press., 2008.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg. Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube. Writing Science. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Schneider, Arnd. Appropriation as Practice: Art and Identity in Argentina. 1st ed. Studies of the Americas. New York, N.Y: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Williams, Raymond. Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.