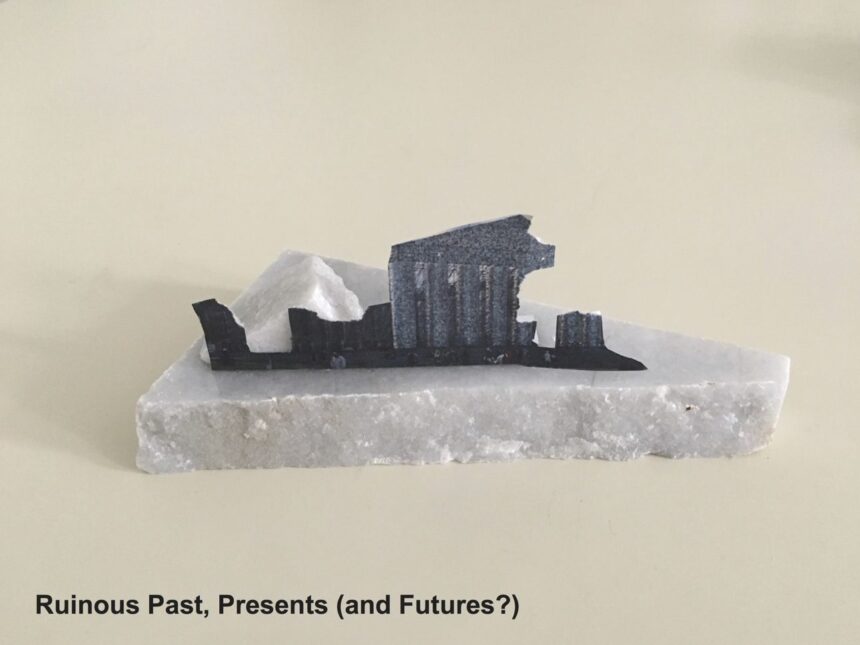

Ruinous Pasts, Presents (and Futures?)

Eleana Yalouri

Participants: Campus Novel (Giannis Cheimonakis, Giannis Delagrammatikas, Foteini Palpana, Yiannis Sinioroglou and Ino Varvaniti), art collective | Fotini Gouseti, visual artist |Sofia Grigoriadou, visual artist | Celina Lage, Transdisciplinary Artist | Giorgis Manoudakis, student of anthropology | Anna Pantelakou, student of theory and history of art | Giorgos Sakkas, anthropologist | Fay Zika, philosopher|

Workshop Co-ordinator: Eleana Yalouri

Do ruins care about the present? A wide range of people from backgrounds as diverse as socio-cultural anthropology, art, philosophy, and art history and theory got together to tackle this question and were thus obliged to confront both the local and the more general histories of ruins.

Ever since the Renaissance, Western artists have been fascinated and inspired by the subject matter of ruins, ruination, and the corresponding imagery as an aesthetic trope and as an allegory for matters involving the ephemeral and the eternal, memory and oblivion, presence and absence, life and mortality, creation and destruction, wholeness and fragmentation. This recurrence of ruins has taken different forms in various contexts from the eighteenth-century Romantic aesthetics of fragmentation and decline, through modernist visions of urban reconstruction and renovation, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, to Cold War prospects of destructive nuclear futures and, more recently, in the prism of ongoing fears of industrial, environmental, or financial ruination.

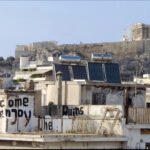

Ancient Greek ruins in particular have enchanted artists and travellers alike since at least the late sixteenth century. More recently, different kinds of ruins, those of the proverbial financial Greek crisis, have inspired and enticed artists, students, activists, and tourists who moved to Athens to experience, assist with, and express their own perspectives on this [latest] Greek tragedy. Ruins may be relics of and gateways to the past, but they also point the way ahead. Despite their dilapidation, they persist, and they act as trigger points to contemplate, imagine, and envision the future.

documenta 14 “Learning from Athens” could be seen in the context of the more general interest taken by a politically sensitive international art world in the urban ruins of the economic crisis and in contemporary art’s eagerness to re-imagine a new revolutionary future. Ruins have also played a central role in the history of documenta itself as an art institution: the ruins of WWII, in the midst of which the first documenta was staged in Kassel, served as a prism through which documenta imag(in)ed and explored its possible futures. Subsequent iterations of documenta have involved venues such as Cairo and Kabul which, according to the official site of documenta 13, ‘have also witnessed destruction through war and the need for reconstruction […]’. Originally planned as a secondary event to accompany the Bundesgartenschau (the biennial horticultural show in Kassel), the first documenta alluded to the ruins of the war and how, through the metaphor of gardens, the memories they evoked could be transcended. documenta 14 exhibited artworks in landscaped archaeological sites (e.g. in Aristotle’s Lyceum, the Athenian Agora, on the Philopappos Hill, etc), once again highlighting the relationship between ruinous pasts and gardens as a source of life and renewal.

Our workshop Ruinous Pasts, Presents (and Futures?) drew from some of documenta 14’s “Learning from Athens” concerns and concepts by taking into account the background of the intertwined historical trajectories of interest in ancient Greek (and other) ruins. The participants worked on and with documenta 14 artworks as well as with other artworks that have drawn on, or alluded to, ancient and contemporary ruins. We worked with concepts and topics, such as ‘ancient and contemporary ruins’, ‘the original and the copy’, ‘the ephemeral’ and ‘the monumental’, ‘debris’ and ‘the venerated’. But we also worked with materials that helped us address these concepts and topics, e.g. fragments of marble, photocopy paper, soap, digital material, archives. We worked independently and together. We exchanged, juxtaposed and experimented with images, ideas, texts and things in order to produce works that fell in between different fields of theory and practice.

For example, Campus Novel provided us with fragments of marble collected from their field trips to marble workshops in the suburbs of Athens, which we then worked on and transformed to produce mementos of our intellectual engagements with ruins and ruination. Their thoughts on monumentality, precariousness and value were expanded on by Anna Pantelakou to discuss her own engagements with and experiences of the d14 hierarchy as a d14 invigilator. Giorgis Manoudakis translated the concept of monumentality from the hierarchies of the art world to the hierarchies of academia to reflect on the monumental aspects of academic knowledge. Fotini Gouseti drew our attention to the ruins and materialities of social clashes and art politics that were also embodied in the cracks in the marble-clad building of the Polytechnic School at Athens where our workshop was accommodated. Sofia Grigoriadou reflected on the idea of the ruin as an exhibit and a work of art, as well as on the cathartic role of the ruin or a work of art, which often acts as an antidote to, consolation for, or distraction from, present crises. Through the prism of her own ‘black mirrors’, including smart phone and camera, Celina Lage linked her own peripatetic wanderings around ruinous landscapes with those of earlier artists. Eleana Yalouri suggested the concept of a quiz that played with ideas of ‘the copy’ and ‘the mirror’, another central concern in the main d14 curatorial concept, as a means of reflecting on the similarities between past and present readings of the Athenian ruins. Fay Zika introduced us to the bliss of gardens as paradises on earth as well as the melancholy brought on by their loss and death. She also traced gardens’ connections with ruins and their involvement in the politics of display and concealment vis-à-vis various kinds of spectators in the past and the present. Giorgis Manoudakis and Giorgos Sakkas made audiovisual recordings of all our meetings and discussions.

All these works, exhibited on the walls of the space that hosted the learning from documenta closing event, belong in an indeterminate and dynamic space between different fields of theory and practice. They help us rethink our research tools and the concepts we use as artists, social scientists, art theorists and/or philosophers, and reconsider research as a form of artistic (or other) implementation of knowledge.

Eleana Yalouri is an Associate Professor at the Department of Social Anthropology at Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences in Athens, Greece. She has a BA in Archaeology (University of Crete, Greece) an MPhil in Museum studies (University of Cambridge) and a PhD in Social Anthropology (University College London), while she undertook postdoctoral research at Princeton University, USA. She has been a visiting lecturer at the University of Westminster, London, and at the University of Malta, and a lecturer at the Department of Anthropology of University College London. Her teaching, research interests and her publications in periodicals and edited volumes include the following issues: Theories of Material Culture; issues of national identity and the representation of the past; cultural heritage and the politics of remembering and forgetting; theories of space and the social construction of landscape; anthropology and art; anthropology and archaeology. Her current research projects involve collaborations with visual artists and art historians exploring the borders between contemporary art and fields of inquiry dealing with the material culture of the past or present, such as archaeology and anthropology.