The “Death” of the Unknown Spectator: documenta 14 exhibition at the Pireos Annexe of Benaki Museum, Athens

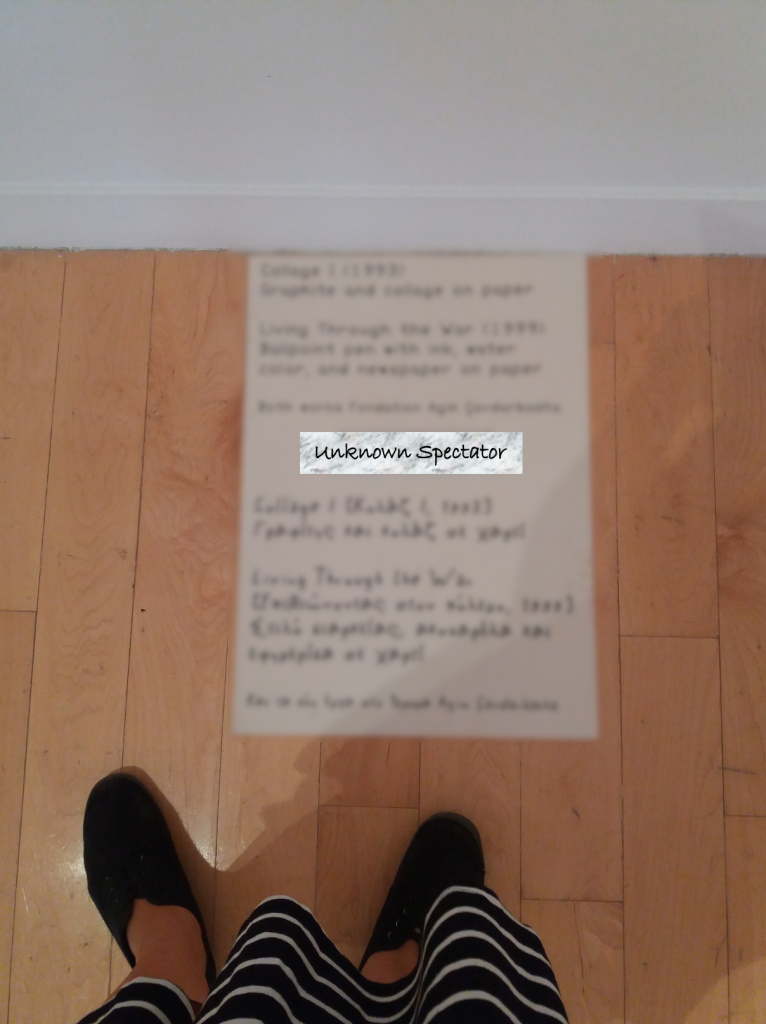

The “Death” of the Unknown Spectator: documenta 14 exhibition at the Pireos Annexe of Benaki Museum, Athens [1]Kyveli Lignou-Tsamantani  Photograph of a label at documenta 14 exhibition at the Pireos Annexe of Benaki Museum, Athens. Photo taken and appropriated by the author. Many things have been written about documenta 14 (d14). Yet, not many have examined the case of the exhibition at the Benaki Museum in Pireos, Athens. This exhibition was quite big, including more than ten rooms with works by sixteen artists or artistic groups. According to the curatorial statement for this space: At the Pireos Annexe, which thus far has been used to present a diverse program of guest exhibitions, beyond the scope of the Benaki’s permanent collection, there is an opportunity to investigate untold, unfinished, or otherwise overshadowed histories and to take inspiration from novel museologies, such as those put forth by artists themselves.[2] Pireos Benaki was one of the four main spaces of the Athenian part of d14, among the Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), the Athens School of Fine Arts (ASFA) and the EMST/National Museum of Contemporary Art.[3] Although most of the spaces of d14 in both cities, Athens and Kassel, included political art, the Pireos Benaki exhibition had as a common thread to show “otherwise overshadowed histories,”[4] which primarily concerned instances of violence, suffering and death. This was at least the theme for half of this show, while the rest seemed to aim to examine “novel museologies.”[5] Although the main challenge of the exhibition not having sufficient contextualization was common also in other spaces of the Athenian part of d14, the subject matter of this particular show rendered this absence of context troublesome. The artworks at Pireos Benaki touched upon many different turbulent historical events, such as the Second World War, the Armenian genocide of 1915, the student uprisings in Bangkok and Athens in 1973, the wars in Kosovo in the ’90s, and the violent colonial history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Such artworks would require from the spectator an informed understanding of the historical incident and its political importance. When talking about photographs of suffering, Susan Sontag argues that “[a] narrative seems likely to be more effective than an image. Partly it is a question of the length of time one is obliged to look, to feel.”[6] Of course, the exhibition at Pireos Benaki did not display photographs, and therefore this quote needs to be adapted for political artworks instead of “images.” However, Sontag’s words touch on what is at stake here: an image of death or suffering without substantial contextualisation raises the risk of not assisting a spectator in developing an ethical response towards violent histories. Such responses are preceded by acknowledging that an “other” has suffered, and hence what needs to come first is an understanding of what one is looking at. This problematic character of this exhibition was the result of many different difficult histories being submerged into a historically conflated narrative, which did not allow the spectator to apprehend the specificity of each individual case. In other words, the mere placement of “untold, unfinished, or otherwise overshadowed histories” together does not mean that it allows them to be really seen and heard, especially when there is no explanation for why certain works are placed next to each other. This analysis aims to question the lack of contextualization in the first part of the Pireos Benaki exhibition that displayed all these different “histories.” The lack of contextualization can be traced to the lack of consistent explanatory labels (wall texts) for each individual artwork or room of the show. In most cases, the labels that existed in the space provided only basic information on the artwork, such as the artist’s name and the artwork’s title, date and material, with very few exceptions that included shorter or longer texts. In all cases, the labels did not imply any connecting tissue among the chosen artworks. Each label was made from whitish canvas and was placed on the floor. Almost in the middle of this canvas was placed a rectangular piece of marble, on which was inscribed the name of the artist in black letters. The format of the labels made them look almost like individual objects with specific aesthetic attributes. Interestingly enough, despite the vast number of texts written for d14, very few questioned the choice of labelling at the Athenian venues of the exhibition. By taking the choice of labelling as a visual metaphor of a “grave,” as explained below, this analysis will examine how the lack of contextualization strips from the spectator their primary role: to look at “political” art[7] and apprehend what they are looking at. The spectator’s inability to read and understand these “histories” leads to their conceptual “death.” Although this call for contextualization via in situ texts bears the danger of implying the need for some kind of didacticism, returning almost to a 19th-century educational museological purpose[8], this is far from the intention of this analysis. What will be problematized here is: how can one acknowledge the specificity of suffering, violence and death and allow them to be heard if the contextualization that would enable them to be understood is missing? Jennifer Allen begins her introduction to “100 days over 20 years” of frieze on Documenta volume by asking: “When does contemporary art turn into art history? What will ‘now’ look like in five, ten, twenty years time?”[9] This question should lie at the core of the analysis of contemporary art exhibitions. Exhibitions such as d14, apart from “writing” visual narratives regarding turbulent historical events, also create an additional page in the still-to-be-written contemporary art history. Nowadays, in particular given that we experience on a global level various socio-political, financial and humanitarian crises, the curators of such large-scale shows are responsible for what the next page on this art historical “narrative” will be – especially when the “subject matter” is recent violent histories. Having said that, I do not mean to imply that curators of such large-scale international shows are the only actors who will remain in history for what they had to say. However, the fact that exhibitions such as documenta or the Venice Biennial are visited by thousands of people from all over the world, and gain incredible publicity in the artworld-related and mass-circulation press, indicates that the curatorial choices in these contexts are of particular importance for shaping people’s opinions and understanding of contemporary art, as well as of recent histories. As Terry Smith aptly suggests regarding the state of contemporary curating, “[c]urators now talk more often, and more publicly, about what they do and how they do it.”[10] This was the case also with d14, which admittedly built a vast discourse around the work both with the written material, as for example the Daybook or the Reader, and with the extensive program of public events.[11] However, such discourse was mostly absent from the space of the exhibition, creating thus a somewhat paradoxical condition of a poorly contextualized in situ spectatorship. In this context, this curatorial stance did not do justice to all those events of violence and suffering. At the same time, it did not assist the spectator in creating an informed understanding of what the “depicted” others have experienced.[12] This would not have been of such importance if the exhibition as a whole had either a more clearly stated curatorial rationale or if at least the material were organised around specific topics, chronological frameworks or types of violent events. The analysis will begin by briefly exploring what some of these “histories” displayed at the first three large spaces of Pireos Benaki were. The exhibition started with the very compelling installation of the Israeli artist Roee Rosen, Live and Die as Eva Braun (1995-1997), which demands the spectator to see the point of view of Hitler’s mistress. This piece, which was one of the most discussed artworks of this exhibition, was comprised of ten hanging banners with long texts and painted images between them. As one can read on the d14 website, “[t]he work lays out a script that inverts the parameters of accepted histories and gives voice to the absurdity and obscenity of what is deemed unspeakable.”[13] The same information could be found on the documenta 14: Daybook.[14] The only information that one could find in the label of this installation – in order of appearance, both in the Greek and English captions – was the title of the work, the date, the material, information for the collection in which the piece belongs, and the name of the artist.[15] This format of caption and a similar amount of information was provided for most of the artworks in the space. This is indicative of how, despite the fact that the Athenian part of d14 was mostly admission free, in reality, its curatorial choices were creating an issue of conceptual accessibility. In the next room, one encountered the canvas scrolls from the series Each night put Kashmir in your Dreams (2003-2014) by Nilima Sheikh. Every multicolor scroll combined images and text, drawing from poetry and history among others, in a way that “plots the cartography of pain, grief, and violence which maintains a hold over the Kashmir valley and its people—caught in the struggle between calls for communal freedom and the hegemonic forces of nationalism,” as the website of d14 mentions.[16] This geographical region has faced many turbulent events linked with colonial histories[17], something that was only understood in situ if the visitor had excellent historical knowledge. Next to Sheikh’s work was placed Arin Rungjang’s painting and video installation And Then There Were None (Tomorrow We will become Thailand) (2016). This was one of the sporadic exceptions of artworks that had an explanatory caption, which indicated to the spectator that the work refers to two historical events that assisted in ending military dictatorships: namely the uprisings in Athens Polytechnic University, Greece, in November 1973 and in the Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand, in October 1973.[18] In contrast to Skeikh’s colorful scrolls hanging next to it, the installation of the appropriated photographic archival material from these two uprisings represented in a photorealistic manner several violent events. In the following small room, Constantinos Hadzinikolaou’s photos, book and video installation Anestis (2017) were displayed. This installation was based on the 1987 Greek novel Tholami by Nikos Kasdaglis, which “depicts an excruciating attempt to escape a violent confrontation (presumably alluding to real events in 1980s Athens).”[19] This violent event of recent Greek history – the killing of the far-left Christos Tsoutsouvis in Athens in 1985 [20] – could be immediately recalled by people of a certain generation or by those familiar with Kasdaglis’ book, but the rest of the spectators would have to search for further information in order to understand it. In a separate room following Hadzinikolaou’s work, there was the video installation Return to Khodorciur – Armenian Diary (1986), by Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi – an interview of a survivor of the Armenian genocide. In this case, apart from the basic caption, the label on the floor also had an explanatory part, which read as follows: “Raphael, Yervant Gianikian’s father, survived the Armenian genocide in 1915 in Eastern Turkey. In April 1988, while living in Venice, sat for his son’s camera and read an excerpt from his memoirs, translated from Armenian into Italian.”[21] Next to this room was a long, descending corridor with canvases on both sides: 101 Works (1973–74) by Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, accompanied by an A4 printed booklet with a one-sentence description for each canvas. As the d14 website explains, these realistic paintings “together form a fractured image of the colonial and political history of the province of Katanga in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (since last year, this province no longer formally exists, having been split into the Tanganyika, Haut-Lomami, Lualaba, and Haut-Katanga provinces).”[22] The exhibition continued with many more artworks. For the purposes of this analysis, the already described artworks are sufficient to make clear how many different histories were placed together in Pireos Benaki. The aforementioned artworks allow one to realise that the curators chose to represent different types of contemporary political art. The spectatorship would have benefited from further in situ information regarding the socio-political and cultural context, which would have allowed a spectator in an Athenian venue to understand the specificity of the events. At Pireos Benaki, the violent histories were dominated by many cases of death and suffering, something that makes the ethics of spectatorship of particular importance. In the text, “Approaches to Displaying Death in Museums: An Introduction,” Elena Stylianou and Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, propose that museums and galleries use “at least four different approaches when it comes to the photographic display of death.”[23] While the d14 exhibition in the Benaki Museum was not a photography exhibition, its subject matter and the use of documentary material (photography or video) partaking in the artworks renders the mention of these “approaches” useful for a consideration of the ethical and political issues of exhibiting death and suffering. These four modes are as follows: first, some exhibitions function as evidence of the past (e.g., in history museums).[24] Second, “The Spectacle of Death” creates the expectation that “photography of death” will “speak for itself, bare of any explanatory material,” something that may lead to “fetishizing and aestheticizing death.”[25] Third, “Empathy and Escaping Anonymity” expects curators to avoid “re-victimization” and “anonymity.”[26] Lastly, “Museums as Agents of Change” approaches the exhibition “as a space for critical reflection and tries to challenge ideological structures by proposing new readings of both the past and the present.”[27] To my mind, the last approach seems to be the most challenging, as the success of any curatorial choice depends equally on two participants – the curator and the spectator – and the latter is not always able, willing or simply prepared to “challenge” their pre-existing knowledge and beliefs. However, it is the curator’s responsibility to assist such processes of “challenging.” If one takes into consideration the d14 statement regarding the Pireos Benaki exhibition, the last approach probably was what they were aiming for. Yet, can such “challenging” take place without sufficient contextualization for each individual artwork? Interestingly enough, a similar view was the main point of criticism in one of the few reviews of the d14 exhibition at Pireos Benaki by Jeniffer Higgie for Frieze magazine. In the review, which considered the exhibition rather successful towards its set goals, Higgie explains: If I have one criticism of this rich and challenging show, it’s the lack of contextualizing information: no birth or death dates or country of origin are included in the otherwise charming labels, which are arranged on the floor and held in place with a small marble block, inscribed with the artist’s name. I’m the first person to criticize tedious wall texts but given the often very specific geo-political motivation of much of the work on show here, it would have been good not to have to depend on Google […] During the press conference, Szymczyk declared that ‘the great lesson is that there are no lessons.’ I beg to differ. There’s a lot to learn here.[28] Here, by following Higgie’s point regarding the issue of in situ information, I aim to take the analysis a step further and provide a symbolic reading of these labels as a “grave.” However, before doing so, it is important to underline that the issue of contextualizing art with texts in museums and exhibitions is a very debatable topic. Wall texts and labels are often perceived as didactic or patronizing. As the writer, Orit Gat, eloquently puts it: “What do we look at when there’s a text present? Where do our eyes go? […] If a label is aligned with a painting, eyes wander between text and image, comparing authority and subjective experience, looking for the places where text touches what it describes.”[29] Admittedly, a pressing issue with labels is the fact that they might seem to represent some kind of “authority,” the only one able to tell to a spectator how they should experience a show. Yet, in cases such as d14, which was an extremely large-scale show of political art, there is a need for one to have a sense of what they are looking at. As the curator, Ingrid Schaffner, suggests, “I would reiterate that all exhibitions, including monographic ones, are essentially essays. Ever present, the thread of the curator’s vision and thinking is a factor which labels can account for.”[30] Schaffner has provided one of the most detailed accounts on the matter of “wall texts” in exhibitions, where she presents both the issues as well as the importance of their existence. As she explains when talking about Lygia Clark’s work, “in an art world that seeks to be global, this information [political and cultural] need not be discretely tucked away in a genteel brochure or distant panel. It can be a straightforward presence, so that without breaking eye contact, one reads both the panel and the object.”[31] One could read this as being exactly the issue also at the d14 Pireos Benaki show, the spectatorship of which depended on information not present in situ. Of course, as Schaffner underlines that “wall texts” are a type of “ephemeral literature” that the spectator can choose whether they will read or not.[32] And although that is true, there is an ethical responsibility from the side of the curator to assist an informed spectatorship. Otherwise, the lack of contextual information, such as curatorial texts or informative labels, reinforces the anonymity of the sufferers, creating thus a rather troubling spectacle of many different deaths from political events that cannot and should not be conflated. One could argue here that the d14 curatorial team did not purposely create a historical “patchwork.” Yet, the parallel placement of all these artworks together in the same space resulted in the loss of the specificity that is needed for the formulation of any kind of informed consideration of the “depicted” others. The latter would demand the spectator to be able to take into account the socio-political circumstances examined by each artwork. So, the dead remains unknown to the spectator if the latter does not have access to the web and/or to the d14 Daybook. Following this, another conceptual “death” takes place at the same time. These curatorial choices could be read as creating the “death” of the unknown spectator. This metaphor can come up to one’s mind when considering the format and placement of the only labels that existed in the exhibition space; the “charming labels,” as Higgie calls them.[33] As already highlighted at the beginning of the article, the labels in the Athenian d14 were placed on the floor, most often being long rectangular columns with a rectangular piece of marble in the middle. It is interesting to bear in mind that this format of labels existed only in the Greek part of d14, while the exhibitions in Kassel had a more conventional style of labelling – usually a caption on the wall. At the close of d14 at the Athenian venues, these canvas labels were covered with footprints, transmitting hence a second message: the spectator was here. The format of the Athenian labels can assist in unpacking the reading of the labels as a symbolic “grave” of the unknown spectator. By bearing in mind the anonymity and unidentified character of this spectator, this symbolic “grave” echoes the tradition of the tombs of the unknown soldiers’ memorials, from which the title of this essay is inspired.[34] Interestingly, in museology, the labels on the wall are called “tombstones.”[35] According to the Harvard Art Museums, “this macabre moniker is the traditional term used to refer to a bare-bones (ahem) label.”(sic)[36] In the case of the Athenian d14, this term takes an even more “macabre” tone with the shift from vertical to horizontal, which reminds one of the horizontality of a grave. Of course, despite being visually interesting, the positioning of the labels on the floor made the reading of longer texts challenging as one would have to lean over the long canvas. However, as these were not providing sufficient information, that was not often an issue, meaning that the spectatorship did not depend on reading them. Another essential element of the format of the labels was the piece of marble. Was this just an aesthetically pleasing choice or rather a choice that underlined some kind of “symbolic capital”?[37] A rather obvious response could be linked with the “local” character of marble. Documenta aimed to learn from Athens, a city in which marble can be found in abundance; hence the use of the specific material could underline even more this “local” character of an otherwise German and international institution. Marble, when encountered in a Greek context where the visitor is supposedly seeking to learn something from Athens, or at least to understand what d14 learned from Athens, carries certain connotations as a renowned Greek material, linked of course also with monumental architecture. In Greece, the archaeological spaces and memorials are full of marble, while marble is widely existent in the interior of many buildings in Athens, as for example, on staircases. However, for my interpretation, the most crucial connotation can be found in the use of marble in Greek cemeteries of the recent past and present for the construction of graves. Hence, the piece of marble on these – mostly non-explanatory – labels could be metaphorically read as sealing the “grave” of a spectator’s ability to understand the curatorial rationale and consequently acknowledge the different histories of violence. The spectatorship in this context does not assist the ethical ramifications that accompany violent events to be brought into the surface. The purpose of the spectatorship is stripped away from the spectator, transforming them into a simple visitor of a museum, who cannot be seen as an active participant; a participant who will be motivated to learn, think and acknowledge through the process of looking at something. Therefore, it seems that d14’s choice of labels in the Athenian venues moved a step beyond the relatively common “death of the author,” or here, of the artist.[38] Even if one is an avid supporter of the “death” of the artist – which quite often artists themselves are too, by supporting that art should speak for itself – in the case of the exhibition at Pireos Benaki, both the “overshadowed histories” and the actual artworks were sacrificed on the curatorial altar. Artworks – even some of the most demanding political ones – with entirely different purposes or meanings were placed next to each other. The meaning of the artworks was undermined, and an acknowledgement of violent histories was rendered impossible. And while many of us would agree that the “artist” was put in their grave without significant issues, the unexpected collateral damage was the spectator. The horizontally placed labels – “graves” – with their footprints remained as the contemporary memento of a troublesome spectatorship. The spectator’s experience was diminished by disarming them of any information that would allow an informed, critical and ethical engagement with the visible – and/or invisible – “depicted” other. The unknown spectator of the contemporary exhibition can now rest in peace. Kyveli Lignou-Tsamantani is an art historian based in York and Athens. Recently she finished her doctoral studies in the History of Art Department at the University of York, UK (funded by the AHRC through WRoCAH and the A.G. Leventis Foundation). She holds an MA in History of Art, the University of York and a BA in Theory and History of Art from the Athens School of Fine Arts, Greece. Her research interests focus on contemporary representations of atrocities and violence in art and photography, the ethics of spectatorship, and issues of visibility. She has worked in exhibitions and public programmes in Greece and the United Kingdom and has participated in research projects in the Athens School of Fine Arts and Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences, Greece. Endnotes [1] In this text I use the term “spectator” instead of “viewer” to be aligned with the terminology used by the artistic director of documenta 14, Adam Szymczyk, in his writing, when referring to Tony Bennett’s rationale; there he talks about “invited artists,” “the team organizing the exhibition” and “the expected spectators.” Adam Szymczyk, “14: Iterability and Otherness – Learning and Working from Athens,” in The documenta 14 Reader, edited by Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017), p. 24. [2] “Benaki Museum—Pireos Street Annexe,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, [3] “Athens Venues,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, https://www.documenta14.de/en/public-exhibition/#venues-athens [4] “Benaki Museum—Pireos Street Annexe,” documenta14. [5] Ibid. [6] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Penguin, 2004), p. 110. [7] I recognize here that the term “political” might be considered rather problematic by some, as every artwork by its mere existence in the socio-political sphere can be considered as such. Hence, here I am using the word in quotation marks to carefully refer to works that deal with actual socio-political events. [8] Such ideas could also be problematised in conjunction with the so-called “educational turn” in curatorial studies. For more on the “educational turn” see Paul O’Neill & Mick Wilson, eds., Curating and the Educational Turn (London: Open Editions/de Appel, 2010). For a brief history of exhibition making see Dorothee Richter, “A Brief Outline of the History of Exhibition Making,” On Curating, Issue 6 (1,2,3, — Thinking about exhibitions): p. 28-37, accessed May 24, 2021, www.on-curating.org/files/oc/dateiverwaltung/old%20Issues/ONCURATING_Issue6.pdf [9] Jennifer Allen, “Introduction: 100 Days over 20 Years,” in frieze on documenta, edited by Jennifer Allen (London: Frieze Publishing, 2012), loc. 60 of 3025, Kindle. [10] Terry Smith, Talking Contemporary Curating (New York: Independent Curators International, 2015), p. 14. [11] Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (eds), documenta 14: Daybook (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017); Latimer and Szymczyk (eds), The documenta 14 Reader. [12] Here the verb “depicted” is intentionally placed in quotation marks, as the presentation of all those “others” was not always in a figurative manner but was sometimes implied in abstract manner or by textual narratives. In other words, here one should be careful to recognize that it does not exist an indexical relationship between the presented “other” and the image, as it happens in the case of photography. [13] Hila Peleg, “Roee Rosen,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, www.documenta14.de/en/artists/1355/roee-rosen [14] Hila Peleg, “Roee Rosen: August 8,” in documenta 14: Daybook, edited by Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017), n.p. I think it is important to note that the price of the Daybook could be seen as high for an Athenian audience experiencing a severe financial crisis. Hence should not be thought that everyone had access to such sources. [15] Based on notes by the author. [16] Natasha Ginwala, “Nilima Sheikh,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13561/nilima-sheikh [17] Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “Kashmir,” accessed June 30, 2020, www.britannica.com/place/Kashmir-region-Indian-subcontinent [18] Hendrik Folkerts, “Arin Rungjang,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13599/arin-rungjang [19] Katerina Tselou, “Constantinos Hadzinikolaou,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13510/constantinos-hadzinikolaou [20] “Christos Tsoutsouvis,” Wikipedia, accessed May 30, 2021, www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christos_Tsoutsouvis [21] Caption transcribed; notes by the author. [22] “How to Write Painting: A Conversation about History Painting, Language, and Colonialism with Gordon Hookey, Hendrik Folkerts, and Vivian Ziherl,” documenta14, accessed June 30, 2020, www.documenta14.de/en/south/894_how_to_write_painting_a_conversation_about_history_painting_ [23] Elena Stylianou and Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert, “Approaches to Displaying Death in Museums: an Introduction,” in Museums and Photography: Displaying Death, edited by Elena Stylianou and Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert (New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 2. [24] Ibid., p. 2. [25] Ibid., p. 2. [26] Ibid., p. 2. [27] Ibid., p. 2. [28] Jennifer Higgie, “documenta 14: Benaki Museum,” Frieze, April 8, 2017, accessed June 30, 2020, www.frieze.com/article/documenta-14-benaki-museum [29] Orit Gat, “Could Reading Be Looking?”, e-flux Journal, Issue 72 (April 2016), accessed May 25, 2021, [30] Ingrid Schaffner, “Wall Text, 2003/6; Ink on paper; Courtesy the author,” in What Makes a Great Exhibition, edited by Paula Marincola (London: Reaktion Books, 2014), p. 165. [31] Ibid., p. 158. [32] Ibid., p. 156. [33] Higgie, “documenta 14: Benaki Museum,” Frieze. [34] Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier,” accessed May 30, 2021, www.britannica.com/topic/Tomb-of-the-Unknown-Soldier [35] Schaffner, “Wall Text,” p.161-2. [36] “Writing on the Wall,” Harvard Art Museums, accessed May 23, 2021, www.harvardartmuseums.org/article/writing-on-the-wall [37] Here, I echo Y. Hamilakis and E. Yalouri regarding the “symbolic capital” of antiquities. For more see, Yannis Hamilakis, and Eleana Yalouri, “Antiquities as Symbolic Capital in Modern Greek Society”, Antiquity 70, no. 267 (March 1996): p. 117–29, accessed November 8, 2017, doi:10.1017/S0003598X00082934. [38] This idea is the expansion of Roland Barthes’ “The Death of the Author,” in Image, Music, Text, translated by S. Heath (London: Fontana Press, 1977), p. 142-148. |